"To the University of Cambridge, in New-England"

By

Phillis Wheatley

Transcription, correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Students of Marymount University, James West, Amy Ridderhof

15

TO THE UNIVERSITY OF

CAMBRIDGE,university

university

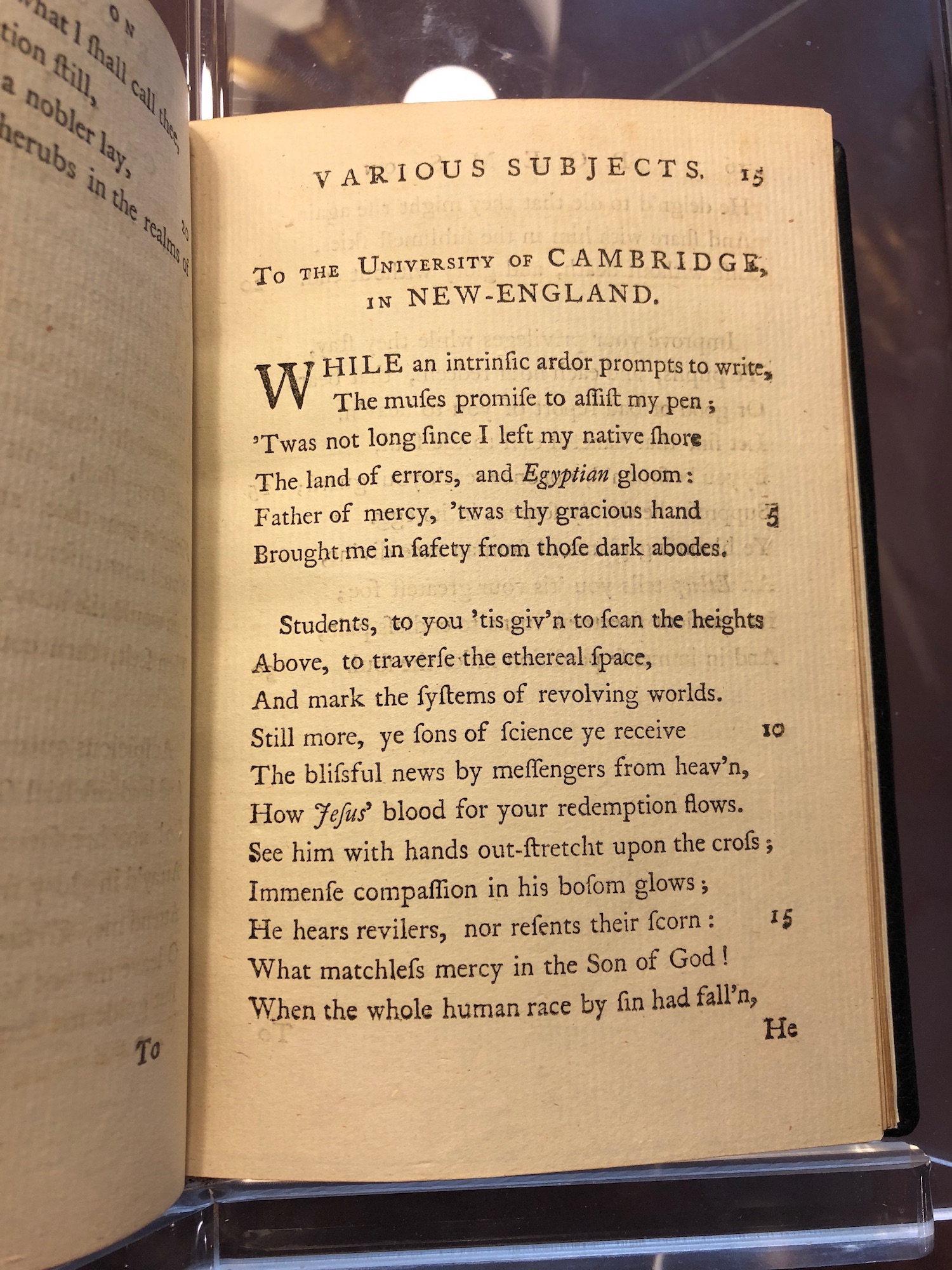

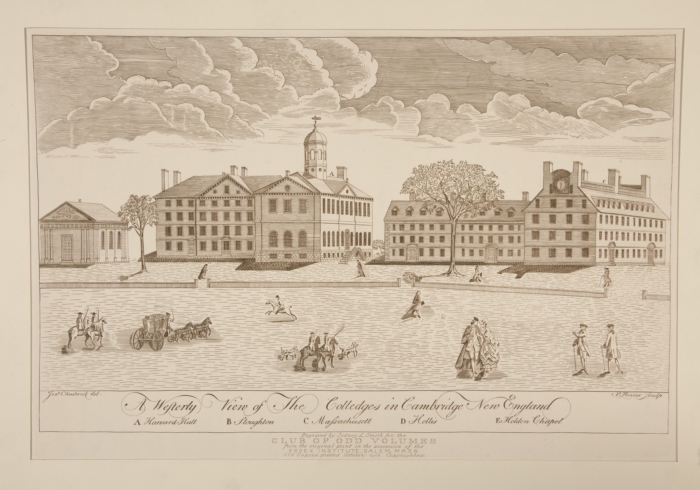

After describing her own educational journey, Wheatley advises students at the

University of Cambridge in New England to appreciate and "[i]mprove" (21) the

privilege of their education by "shunn[ing]" (25) the "transient sweetness" (29)

of sin using a variety of religious images. The University of Cambridge in New

England is now known as Harvard University. According to Katherine

Clay Bassard, Wheatley wrote this poem when she was about fourteen years

old (41). The engraving included here is by Paul Revere and shows "A Westerly View

of The Colledges in Cambridge New England" (1767), via Wikimedia Commons. - [JW] IN NEW-ENGLAND.

1WHILE an intrinsic

ardorardorardorWheatley works from the premise, commonly used among

early women writers and the enslaved who were restricted from intellectual

pursuits like writing, that her desire to write is "intrinsic" (1) or

God-given, and therefore appropriate. The word "ardor" also connotes

physical desire and flame-like passion, according to the OED (n.3). - [JW] prompts to write,

2The musesmusesmusesAccording

to A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology, the Muses are “inspiring goddesses of song" who

“presid[e] over the different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and

sciences." The “invocation of the muse” to aid the poet's work is often used

by neoclassical authors like those whom Wheatley has clearly read and was

influenced by, including Milton and Pope.

However, Hilene Flanzbaum suggests that Wheatley’s notably frequent

invocation of the muse is more significant than formulaic or imitative--it

is “the very means by which she usurps power for herself and claims a berth

for her own thoughts, emotions and desires. And while some may claim that

these functions accompany any appearance of the muse, when the muses bestow

their power on a black female slave, they transport Wheatley to a domain

surprisingly free of restriction and previously forbidden” (“Unprecedented Liberties”

75). - [JW] promise to assist my

pen;

3'Twas not long since I left my native shore

4The land of errors, and Egyptian gloomgloom:gloomWheatley here alludes

to Exodus 10:21-22, wherein the ninth plague of darkness is visited

upon Egypt. This reference is also in line with contemporary Orientalist

notions about Egypt and Egyptian religiosity, which was believed to be full

of occult practices. Early nineteenth-century British historian and scholar

Thomas Maurice explores these ideas of idolatry and superstition in Observations on

the Remains of Ancient Egyptian Grandeur and Superstition. A

detailed focus on the Egyptian religious practices can be found in the

chapter "Strictures on the superstitious rites of the Egyptians,

particularly on the Nefarious Worship paid to Beasts, Esteemed Sacred, and

called in Scripture the Abominations of Egypt" (74-83). The Book of Exodus also describes the Israelites' delivery from enslavement in Egypt. - [JW]

5Father of mercy, 'twas thy gracious hand

6Brought me in safety from those dark abodes.

Students, to you 'tis giv'n to scan the heights

7Above, to traverse the ethereal space,

8And mark the systems of

revolving worldssystems.systems

After describing her own educational journey, Wheatley advises students at the

University of Cambridge in New England to appreciate and "[i]mprove" (21) the

privilege of their education by "shunn[ing]" (25) the "transient sweetness" (29)

of sin using a variety of religious images. The University of Cambridge in New

England is now known as Harvard University. According to Katherine

Clay Bassard, Wheatley wrote this poem when she was about fourteen years

old (41). The engraving included here is by Paul Revere and shows "A Westerly View

of The Colledges in Cambridge New England" (1767), via Wikimedia Commons. - [JW] IN NEW-ENGLAND.

1WHILE an intrinsic

ardorardorardorWheatley works from the premise, commonly used among

early women writers and the enslaved who were restricted from intellectual

pursuits like writing, that her desire to write is "intrinsic" (1) or

God-given, and therefore appropriate. The word "ardor" also connotes

physical desire and flame-like passion, according to the OED (n.3). - [JW] prompts to write,

2The musesmusesmusesAccording

to A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology, the Muses are “inspiring goddesses of song" who

“presid[e] over the different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and

sciences." The “invocation of the muse” to aid the poet's work is often used

by neoclassical authors like those whom Wheatley has clearly read and was

influenced by, including Milton and Pope.

However, Hilene Flanzbaum suggests that Wheatley’s notably frequent

invocation of the muse is more significant than formulaic or imitative--it

is “the very means by which she usurps power for herself and claims a berth

for her own thoughts, emotions and desires. And while some may claim that

these functions accompany any appearance of the muse, when the muses bestow

their power on a black female slave, they transport Wheatley to a domain

surprisingly free of restriction and previously forbidden” (“Unprecedented Liberties”

75). - [JW] promise to assist my

pen;

3'Twas not long since I left my native shore

4The land of errors, and Egyptian gloomgloom:gloomWheatley here alludes

to Exodus 10:21-22, wherein the ninth plague of darkness is visited

upon Egypt. This reference is also in line with contemporary Orientalist

notions about Egypt and Egyptian religiosity, which was believed to be full

of occult practices. Early nineteenth-century British historian and scholar

Thomas Maurice explores these ideas of idolatry and superstition in Observations on

the Remains of Ancient Egyptian Grandeur and Superstition. A

detailed focus on the Egyptian religious practices can be found in the

chapter "Strictures on the superstitious rites of the Egyptians,

particularly on the Nefarious Worship paid to Beasts, Esteemed Sacred, and

called in Scripture the Abominations of Egypt" (74-83). The Book of Exodus also describes the Israelites' delivery from enslavement in Egypt. - [JW]

5Father of mercy, 'twas thy gracious hand

6Brought me in safety from those dark abodes.

Students, to you 'tis giv'n to scan the heights

7Above, to traverse the ethereal space,

8And mark the systems of

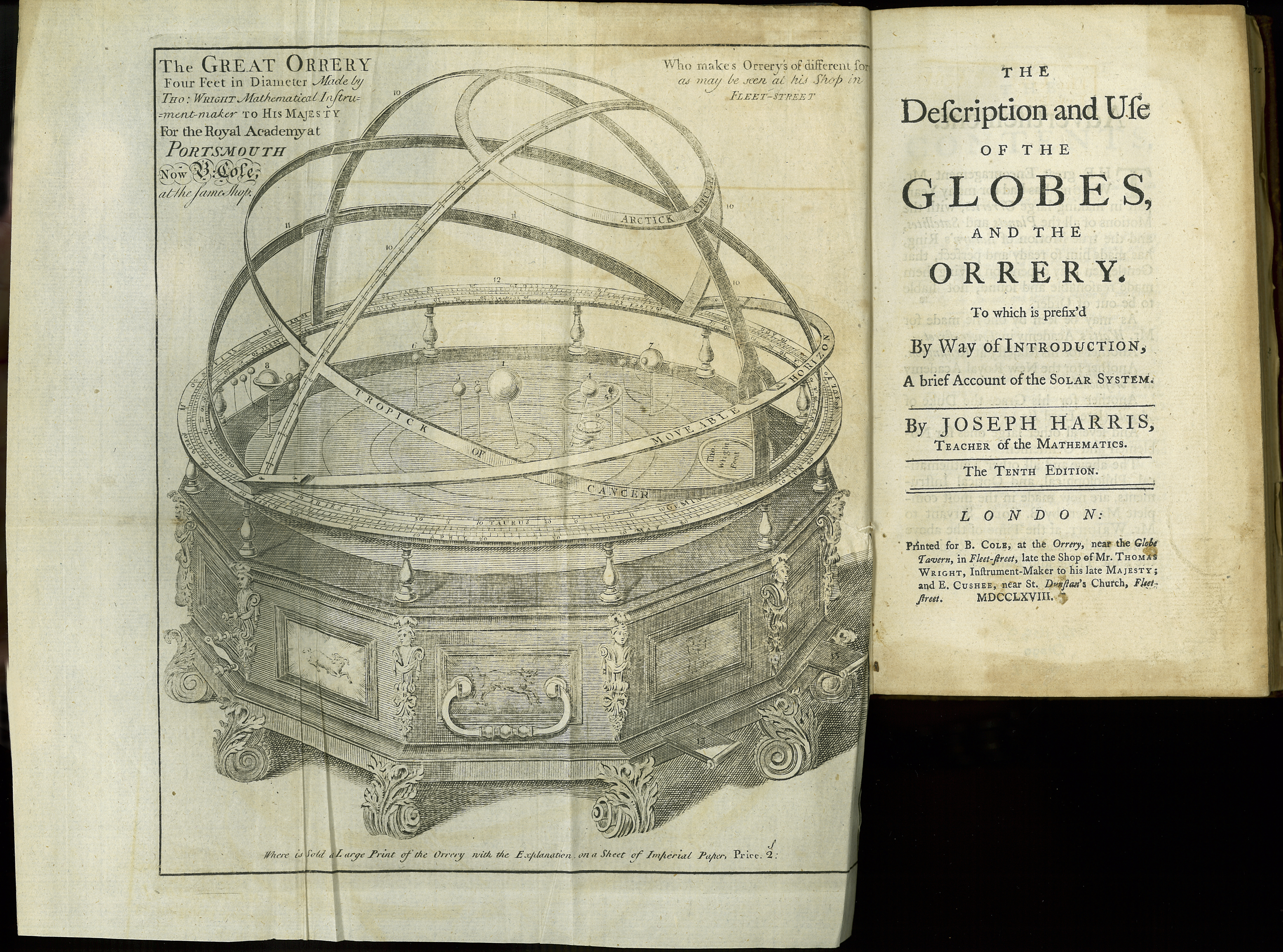

revolving worldssystems.systems The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

development of the microscope and the telescope had made great scientific

advancements possible, especially in astronomy; in the title page and

pull-out image represented here, you can see an eighteenth-century orrery--a

scientific clockwork instrument used to dramatize the motion of the planets

in the solar system (via the University of Otago). Possibly an allusion to

Alexander Pope's 1733-34 Essay on Man (I.23-28), Wheatley here may

also be referencing contemporary scientific thought about the plurality of worlds. - [JW]

9Still more, ye sons of science ye receive

10The blissful news by messengers from heav'n,

11How Jesus' blood for your redemption flows.

12See him with hands out-stretcht upon the cross;

13Immese compassion in his bosom glows;

14He hears revilers, nor resents their scorn:

15What matchless mercy in the Son of God!

16When the whole human race by sin had fall'n,

16

17He deign'ddeigndeign

According to the Oxford English Dictionary deign means "to think

it worthy of oneself" or "to think fit" (n.1a). Today, it typically has a

negative connotation, though it does not here. - [JW] to die that they might rise again,

18And share with him in the sublimest skies,

19Life without death, and glory without end.

20Improve your privileges while they stay,

21Ye pupils, and each hour redeem, that bears

22Or good or bad report of you to heav'n.

23Let sin, that baneful evil to the soul,

24By you be shunn'd, nor once remit your guard;

25Suppress the deadly serpent in its egg.

26Ye blooming plants of human race divine,

27An EthiopEthiopEthiop

The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

development of the microscope and the telescope had made great scientific

advancements possible, especially in astronomy; in the title page and

pull-out image represented here, you can see an eighteenth-century orrery--a

scientific clockwork instrument used to dramatize the motion of the planets

in the solar system (via the University of Otago). Possibly an allusion to

Alexander Pope's 1733-34 Essay on Man (I.23-28), Wheatley here may

also be referencing contemporary scientific thought about the plurality of worlds. - [JW]

9Still more, ye sons of science ye receive

10The blissful news by messengers from heav'n,

11How Jesus' blood for your redemption flows.

12See him with hands out-stretcht upon the cross;

13Immese compassion in his bosom glows;

14He hears revilers, nor resents their scorn:

15What matchless mercy in the Son of God!

16When the whole human race by sin had fall'n,

16

17He deign'ddeigndeign

According to the Oxford English Dictionary deign means "to think

it worthy of oneself" or "to think fit" (n.1a). Today, it typically has a

negative connotation, though it does not here. - [JW] to die that they might rise again,

18And share with him in the sublimest skies,

19Life without death, and glory without end.

20Improve your privileges while they stay,

21Ye pupils, and each hour redeem, that bears

22Or good or bad report of you to heav'n.

23Let sin, that baneful evil to the soul,

24By you be shunn'd, nor once remit your guard;

25Suppress the deadly serpent in its egg.

26Ye blooming plants of human race divine,

27An EthiopEthiopEthiop

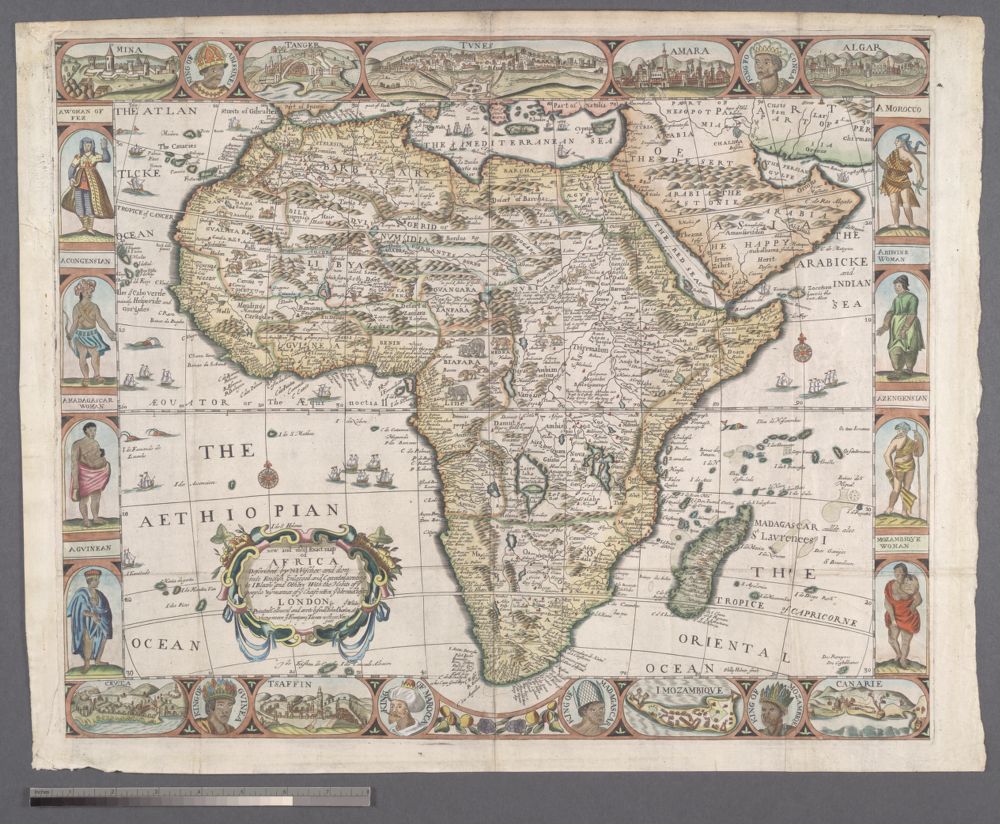

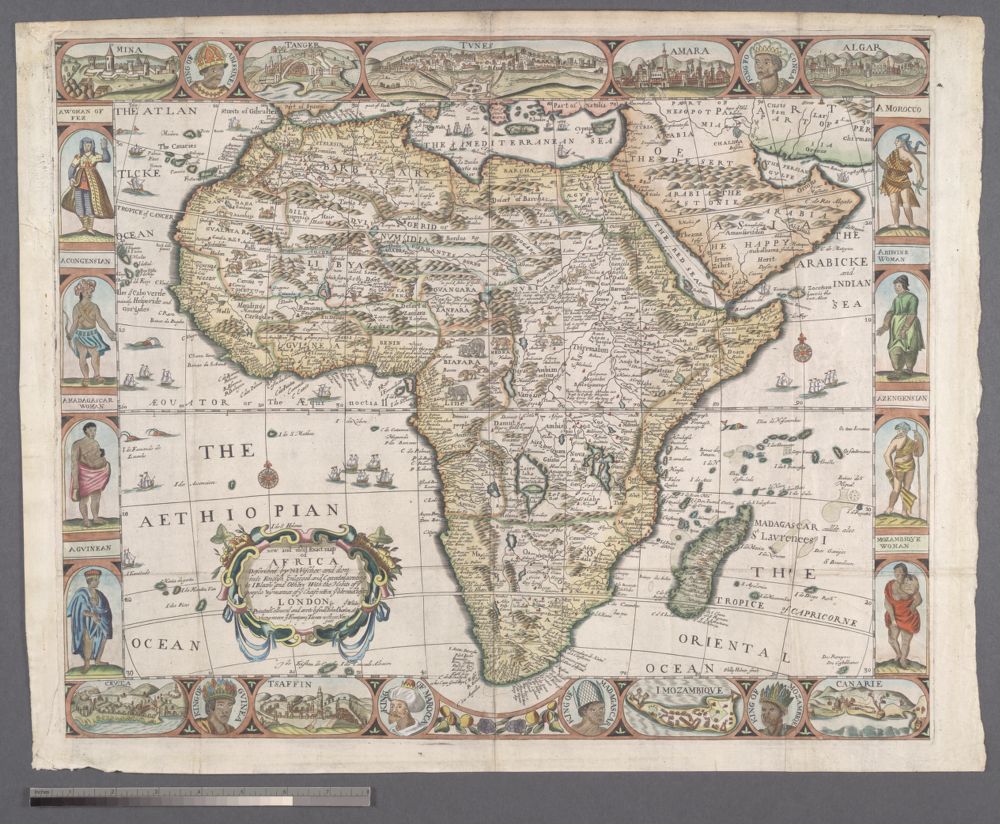

According to the OED, the word Ethiop would have been used during

Wheatley's time most often to refer to "[a] black or dark-skinned person; a

black African," and only occasionally to the country of Ethiopia,

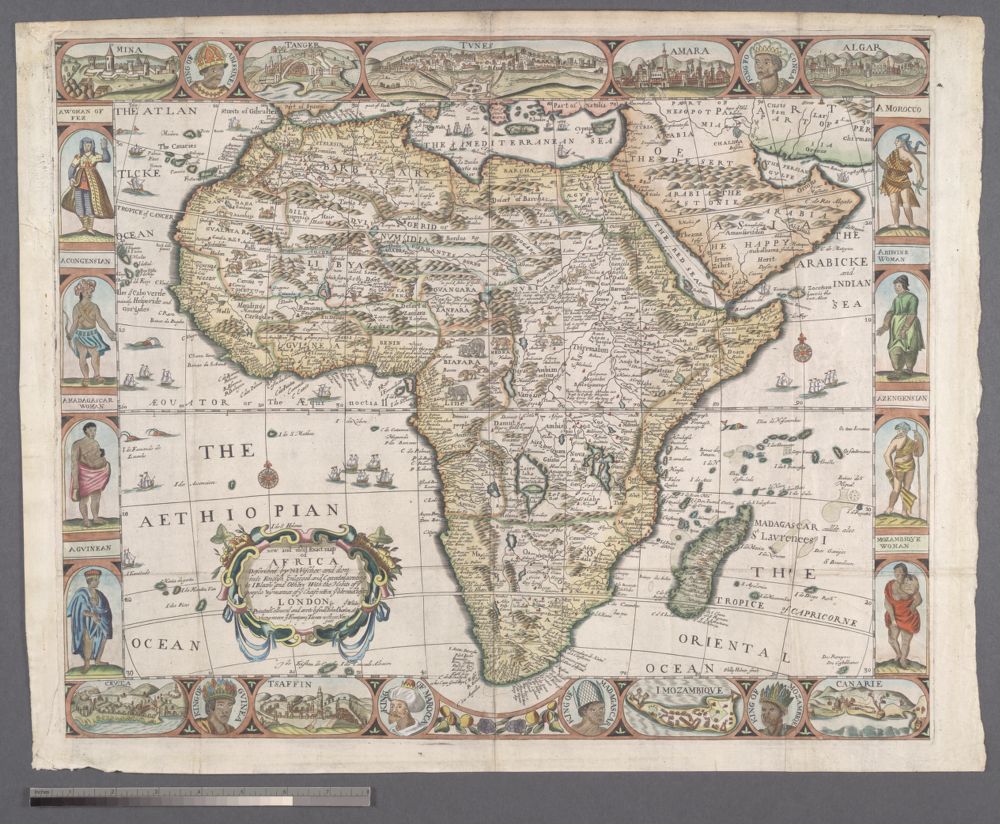

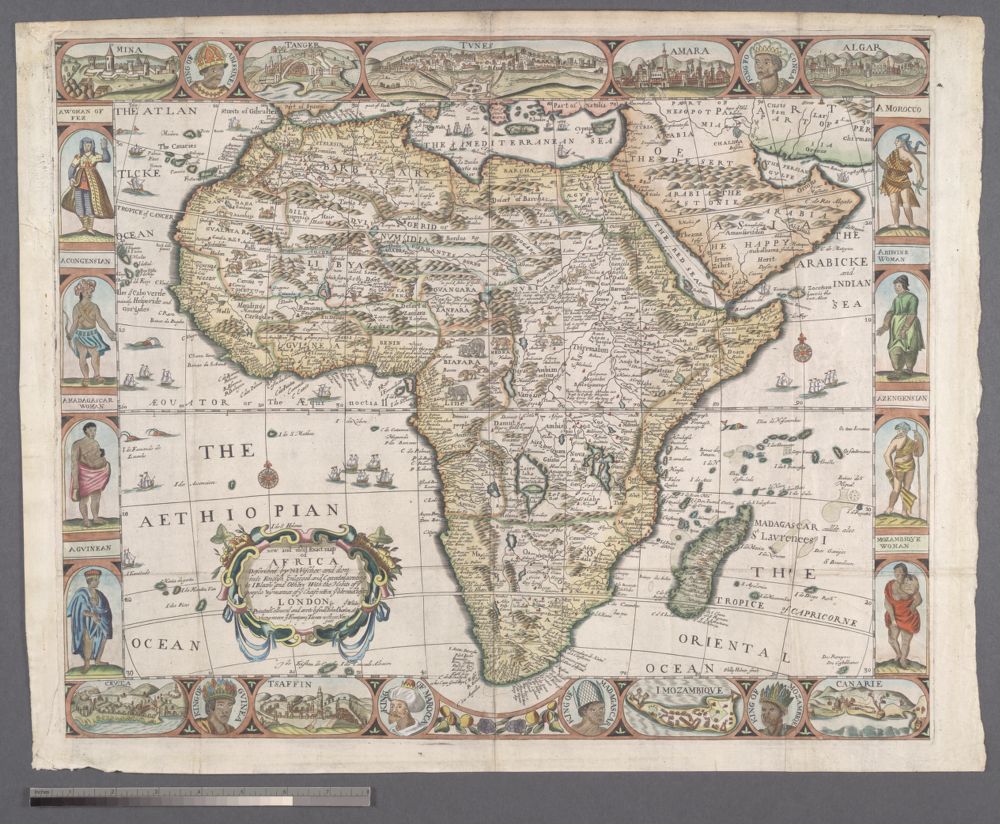

specifically (n.A). Included here, via the Norwich Collection at Stanford University, is a 1666 map

of Africa and the surrounding oceans, embellished with a variety of images.

- [JW] tells you 'tis your greatest foe;

28Its transient sweetness turns to endless pain,

29And in immense perditionperditionperditionIn theological discussion, the word perdition means "the

state of final spiritual ruin or damnation; the consignment of the

unredeemed or wicked and impenitent soul to hell; the fate of those in hell;

eternal death" (OED, "perdition" n.2a). In more general terms, it suggests

ruin or degradation (n.1a). - [JW] sinks the

soul.

17

According to the OED, the word Ethiop would have been used during

Wheatley's time most often to refer to "[a] black or dark-skinned person; a

black African," and only occasionally to the country of Ethiopia,

specifically (n.A). Included here, via the Norwich Collection at Stanford University, is a 1666 map

of Africa and the surrounding oceans, embellished with a variety of images.

- [JW] tells you 'tis your greatest foe;

28Its transient sweetness turns to endless pain,

29And in immense perditionperditionperditionIn theological discussion, the word perdition means "the

state of final spiritual ruin or damnation; the consignment of the

unredeemed or wicked and impenitent soul to hell; the fate of those in hell;

eternal death" (OED, "perdition" n.2a). In more general terms, it suggests

ruin or degradation (n.1a). - [JW] sinks the

soul.

17

After describing her own educational journey, Wheatley advises students at the

University of Cambridge in New England to appreciate and "[i]mprove" (21) the

privilege of their education by "shunn[ing]" (25) the "transient sweetness" (29)

of sin using a variety of religious images. The University of Cambridge in New

England is now known as Harvard University. According to Katherine

Clay Bassard, Wheatley wrote this poem when she was about fourteen years

old (41). The engraving included here is by Paul Revere and shows "A Westerly View

of The Colledges in Cambridge New England" (1767), via Wikimedia Commons. - [JW] IN NEW-ENGLAND.

1WHILE an intrinsic

ardorardorardorWheatley works from the premise, commonly used among

early women writers and the enslaved who were restricted from intellectual

pursuits like writing, that her desire to write is "intrinsic" (1) or

God-given, and therefore appropriate. The word "ardor" also connotes

physical desire and flame-like passion, according to the OED (n.3). - [JW] prompts to write,

2The musesmusesmusesAccording

to A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology, the Muses are “inspiring goddesses of song" who

“presid[e] over the different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and

sciences." The “invocation of the muse” to aid the poet's work is often used

by neoclassical authors like those whom Wheatley has clearly read and was

influenced by, including Milton and Pope.

However, Hilene Flanzbaum suggests that Wheatley’s notably frequent

invocation of the muse is more significant than formulaic or imitative--it

is “the very means by which she usurps power for herself and claims a berth

for her own thoughts, emotions and desires. And while some may claim that

these functions accompany any appearance of the muse, when the muses bestow

their power on a black female slave, they transport Wheatley to a domain

surprisingly free of restriction and previously forbidden” (“Unprecedented Liberties”

75). - [JW] promise to assist my

pen;

3'Twas not long since I left my native shore

4The land of errors, and Egyptian gloomgloom:gloomWheatley here alludes

to Exodus 10:21-22, wherein the ninth plague of darkness is visited

upon Egypt. This reference is also in line with contemporary Orientalist

notions about Egypt and Egyptian religiosity, which was believed to be full

of occult practices. Early nineteenth-century British historian and scholar

Thomas Maurice explores these ideas of idolatry and superstition in Observations on

the Remains of Ancient Egyptian Grandeur and Superstition. A

detailed focus on the Egyptian religious practices can be found in the

chapter "Strictures on the superstitious rites of the Egyptians,

particularly on the Nefarious Worship paid to Beasts, Esteemed Sacred, and

called in Scripture the Abominations of Egypt" (74-83). The Book of Exodus also describes the Israelites' delivery from enslavement in Egypt. - [JW]

5Father of mercy, 'twas thy gracious hand

6Brought me in safety from those dark abodes.

Students, to you 'tis giv'n to scan the heights

7Above, to traverse the ethereal space,

8And mark the systems of

revolving worldssystems.systems

After describing her own educational journey, Wheatley advises students at the

University of Cambridge in New England to appreciate and "[i]mprove" (21) the

privilege of their education by "shunn[ing]" (25) the "transient sweetness" (29)

of sin using a variety of religious images. The University of Cambridge in New

England is now known as Harvard University. According to Katherine

Clay Bassard, Wheatley wrote this poem when she was about fourteen years

old (41). The engraving included here is by Paul Revere and shows "A Westerly View

of The Colledges in Cambridge New England" (1767), via Wikimedia Commons. - [JW] IN NEW-ENGLAND.

1WHILE an intrinsic

ardorardorardorWheatley works from the premise, commonly used among

early women writers and the enslaved who were restricted from intellectual

pursuits like writing, that her desire to write is "intrinsic" (1) or

God-given, and therefore appropriate. The word "ardor" also connotes

physical desire and flame-like passion, according to the OED (n.3). - [JW] prompts to write,

2The musesmusesmusesAccording

to A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology, the Muses are “inspiring goddesses of song" who

“presid[e] over the different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and

sciences." The “invocation of the muse” to aid the poet's work is often used

by neoclassical authors like those whom Wheatley has clearly read and was

influenced by, including Milton and Pope.

However, Hilene Flanzbaum suggests that Wheatley’s notably frequent

invocation of the muse is more significant than formulaic or imitative--it

is “the very means by which she usurps power for herself and claims a berth

for her own thoughts, emotions and desires. And while some may claim that

these functions accompany any appearance of the muse, when the muses bestow

their power on a black female slave, they transport Wheatley to a domain

surprisingly free of restriction and previously forbidden” (“Unprecedented Liberties”

75). - [JW] promise to assist my

pen;

3'Twas not long since I left my native shore

4The land of errors, and Egyptian gloomgloom:gloomWheatley here alludes

to Exodus 10:21-22, wherein the ninth plague of darkness is visited

upon Egypt. This reference is also in line with contemporary Orientalist

notions about Egypt and Egyptian religiosity, which was believed to be full

of occult practices. Early nineteenth-century British historian and scholar

Thomas Maurice explores these ideas of idolatry and superstition in Observations on

the Remains of Ancient Egyptian Grandeur and Superstition. A

detailed focus on the Egyptian religious practices can be found in the

chapter "Strictures on the superstitious rites of the Egyptians,

particularly on the Nefarious Worship paid to Beasts, Esteemed Sacred, and

called in Scripture the Abominations of Egypt" (74-83). The Book of Exodus also describes the Israelites' delivery from enslavement in Egypt. - [JW]

5Father of mercy, 'twas thy gracious hand

6Brought me in safety from those dark abodes.

Students, to you 'tis giv'n to scan the heights

7Above, to traverse the ethereal space,

8And mark the systems of

revolving worldssystems.systems The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

development of the microscope and the telescope had made great scientific

advancements possible, especially in astronomy; in the title page and

pull-out image represented here, you can see an eighteenth-century orrery--a

scientific clockwork instrument used to dramatize the motion of the planets

in the solar system (via the University of Otago). Possibly an allusion to

Alexander Pope's 1733-34 Essay on Man (I.23-28), Wheatley here may

also be referencing contemporary scientific thought about the plurality of worlds. - [JW]

9Still more, ye sons of science ye receive

10The blissful news by messengers from heav'n,

11How Jesus' blood for your redemption flows.

12See him with hands out-stretcht upon the cross;

13Immese compassion in his bosom glows;

14He hears revilers, nor resents their scorn:

15What matchless mercy in the Son of God!

16When the whole human race by sin had fall'n,

16

17He deign'ddeigndeign

According to the Oxford English Dictionary deign means "to think

it worthy of oneself" or "to think fit" (n.1a). Today, it typically has a

negative connotation, though it does not here. - [JW] to die that they might rise again,

18And share with him in the sublimest skies,

19Life without death, and glory without end.

20Improve your privileges while they stay,

21Ye pupils, and each hour redeem, that bears

22Or good or bad report of you to heav'n.

23Let sin, that baneful evil to the soul,

24By you be shunn'd, nor once remit your guard;

25Suppress the deadly serpent in its egg.

26Ye blooming plants of human race divine,

27An EthiopEthiopEthiop

The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

development of the microscope and the telescope had made great scientific

advancements possible, especially in astronomy; in the title page and

pull-out image represented here, you can see an eighteenth-century orrery--a

scientific clockwork instrument used to dramatize the motion of the planets

in the solar system (via the University of Otago). Possibly an allusion to

Alexander Pope's 1733-34 Essay on Man (I.23-28), Wheatley here may

also be referencing contemporary scientific thought about the plurality of worlds. - [JW]

9Still more, ye sons of science ye receive

10The blissful news by messengers from heav'n,

11How Jesus' blood for your redemption flows.

12See him with hands out-stretcht upon the cross;

13Immese compassion in his bosom glows;

14He hears revilers, nor resents their scorn:

15What matchless mercy in the Son of God!

16When the whole human race by sin had fall'n,

16

17He deign'ddeigndeign

According to the Oxford English Dictionary deign means "to think

it worthy of oneself" or "to think fit" (n.1a). Today, it typically has a

negative connotation, though it does not here. - [JW] to die that they might rise again,

18And share with him in the sublimest skies,

19Life without death, and glory without end.

20Improve your privileges while they stay,

21Ye pupils, and each hour redeem, that bears

22Or good or bad report of you to heav'n.

23Let sin, that baneful evil to the soul,

24By you be shunn'd, nor once remit your guard;

25Suppress the deadly serpent in its egg.

26Ye blooming plants of human race divine,

27An EthiopEthiopEthiop

According to the OED, the word Ethiop would have been used during

Wheatley's time most often to refer to "[a] black or dark-skinned person; a

black African," and only occasionally to the country of Ethiopia,

specifically (n.A). Included here, via the Norwich Collection at Stanford University, is a 1666 map

of Africa and the surrounding oceans, embellished with a variety of images.

- [JW] tells you 'tis your greatest foe;

28Its transient sweetness turns to endless pain,

29And in immense perditionperditionperditionIn theological discussion, the word perdition means "the

state of final spiritual ruin or damnation; the consignment of the

unredeemed or wicked and impenitent soul to hell; the fate of those in hell;

eternal death" (OED, "perdition" n.2a). In more general terms, it suggests

ruin or degradation (n.1a). - [JW] sinks the

soul.

17

According to the OED, the word Ethiop would have been used during

Wheatley's time most often to refer to "[a] black or dark-skinned person; a

black African," and only occasionally to the country of Ethiopia,

specifically (n.A). Included here, via the Norwich Collection at Stanford University, is a 1666 map

of Africa and the surrounding oceans, embellished with a variety of images.

- [JW] tells you 'tis your greatest foe;

28Its transient sweetness turns to endless pain,

29And in immense perditionperditionperditionIn theological discussion, the word perdition means "the

state of final spiritual ruin or damnation; the consignment of the

unredeemed or wicked and impenitent soul to hell; the fate of those in hell;

eternal death" (OED, "perdition" n.2a). In more general terms, it suggests

ruin or degradation (n.1a). - [JW] sinks the

soul.

17

Footnotes

_university

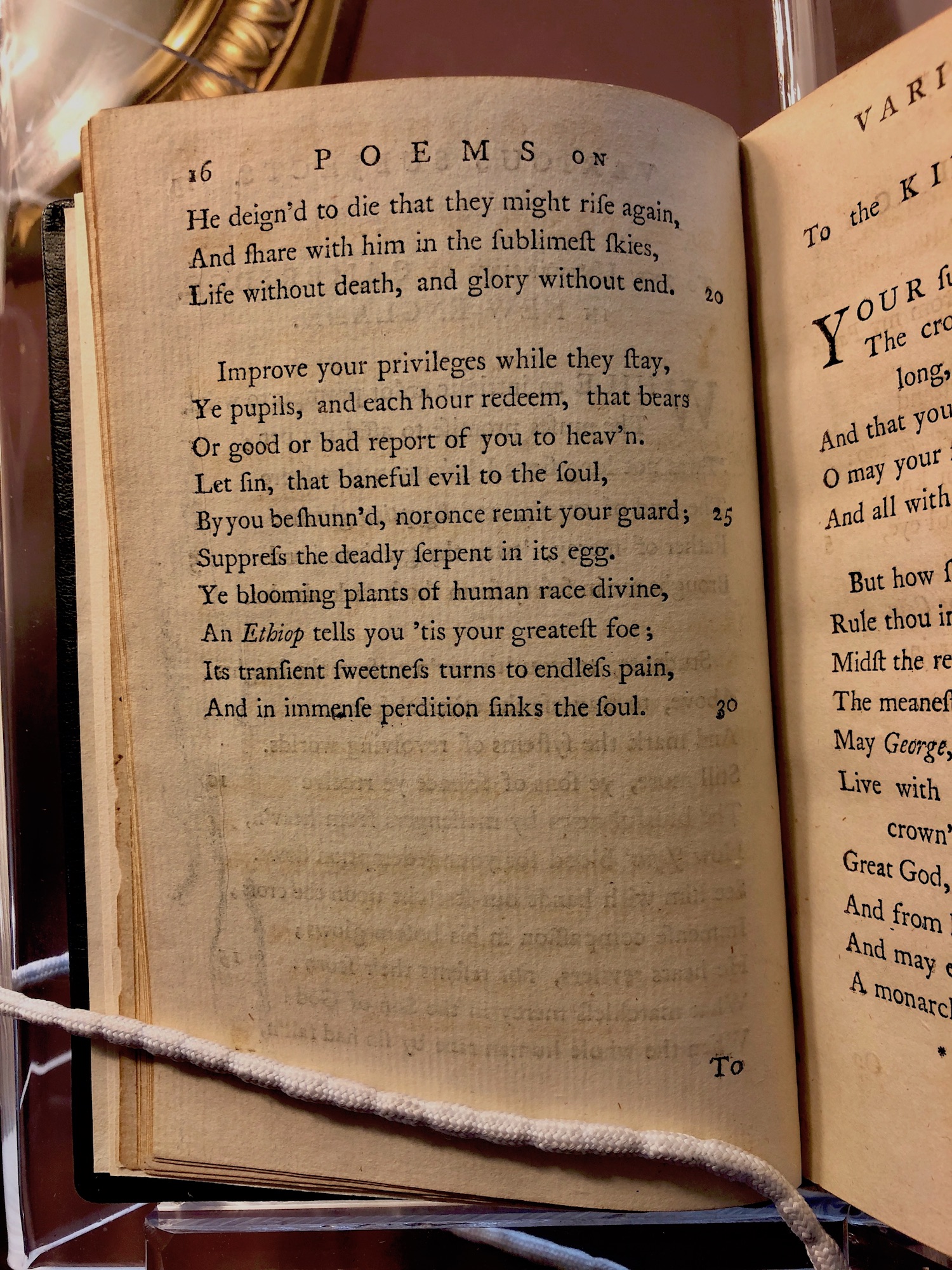

After describing her own educational journey, Wheatley advises students at the

University of Cambridge in New England to appreciate and "[i]mprove" (21) the

privilege of their education by "shunn[ing]" (25) the "transient sweetness" (29)

of sin using a variety of religious images. The University of Cambridge in New

England is now known as Harvard University. According to Katherine

Clay Bassard, Wheatley wrote this poem when she was about fourteen years

old (41). The engraving included here is by Paul Revere and shows "A Westerly View

of The Colledges in Cambridge New England" (1767), via Wikimedia Commons.

After describing her own educational journey, Wheatley advises students at the

University of Cambridge in New England to appreciate and "[i]mprove" (21) the

privilege of their education by "shunn[ing]" (25) the "transient sweetness" (29)

of sin using a variety of religious images. The University of Cambridge in New

England is now known as Harvard University. According to Katherine

Clay Bassard, Wheatley wrote this poem when she was about fourteen years

old (41). The engraving included here is by Paul Revere and shows "A Westerly View

of The Colledges in Cambridge New England" (1767), via Wikimedia Commons.

After describing her own educational journey, Wheatley advises students at the

University of Cambridge in New England to appreciate and "[i]mprove" (21) the

privilege of their education by "shunn[ing]" (25) the "transient sweetness" (29)

of sin using a variety of religious images. The University of Cambridge in New

England is now known as Harvard University. According to Katherine

Clay Bassard, Wheatley wrote this poem when she was about fourteen years

old (41). The engraving included here is by Paul Revere and shows "A Westerly View

of The Colledges in Cambridge New England" (1767), via Wikimedia Commons.

After describing her own educational journey, Wheatley advises students at the

University of Cambridge in New England to appreciate and "[i]mprove" (21) the

privilege of their education by "shunn[ing]" (25) the "transient sweetness" (29)

of sin using a variety of religious images. The University of Cambridge in New

England is now known as Harvard University. According to Katherine

Clay Bassard, Wheatley wrote this poem when she was about fourteen years

old (41). The engraving included here is by Paul Revere and shows "A Westerly View

of The Colledges in Cambridge New England" (1767), via Wikimedia Commons._ardorWheatley works from the premise, commonly used among

early women writers and the enslaved who were restricted from intellectual

pursuits like writing, that her desire to write is "intrinsic" (1) or

God-given, and therefore appropriate. The word "ardor" also connotes

physical desire and flame-like passion, according to the OED (n.3).

_musesAccording

to A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology, the Muses are “inspiring goddesses of song" who

“presid[e] over the different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and

sciences." The “invocation of the muse” to aid the poet's work is often used

by neoclassical authors like those whom Wheatley has clearly read and was

influenced by, including Milton and Pope.

However, Hilene Flanzbaum suggests that Wheatley’s notably frequent

invocation of the muse is more significant than formulaic or imitative--it

is “the very means by which she usurps power for herself and claims a berth

for her own thoughts, emotions and desires. And while some may claim that

these functions accompany any appearance of the muse, when the muses bestow

their power on a black female slave, they transport Wheatley to a domain

surprisingly free of restriction and previously forbidden” (“Unprecedented Liberties”

75).

_gloomWheatley here alludes

to Exodus 10:21-22, wherein the ninth plague of darkness is visited

upon Egypt. This reference is also in line with contemporary Orientalist

notions about Egypt and Egyptian religiosity, which was believed to be full

of occult practices. Early nineteenth-century British historian and scholar

Thomas Maurice explores these ideas of idolatry and superstition in Observations on

the Remains of Ancient Egyptian Grandeur and Superstition. A

detailed focus on the Egyptian religious practices can be found in the

chapter "Strictures on the superstitious rites of the Egyptians,

particularly on the Nefarious Worship paid to Beasts, Esteemed Sacred, and

called in Scripture the Abominations of Egypt" (74-83). The Book of Exodus also describes the Israelites' delivery from enslavement in Egypt.

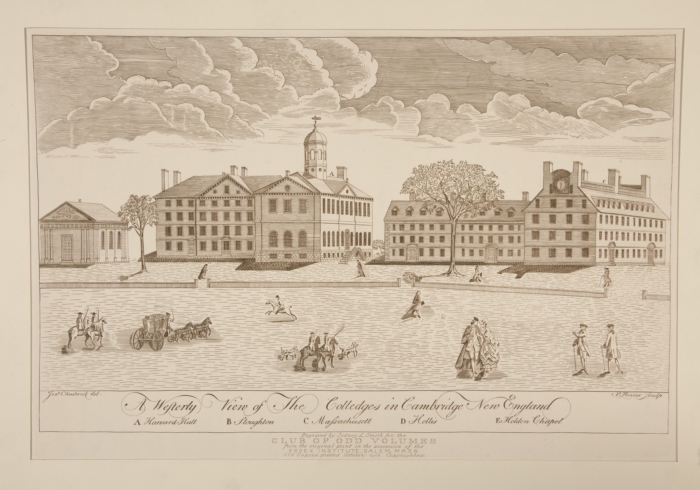

_systems The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

development of the microscope and the telescope had made great scientific

advancements possible, especially in astronomy; in the title page and

pull-out image represented here, you can see an eighteenth-century orrery--a

scientific clockwork instrument used to dramatize the motion of the planets

in the solar system (via the University of Otago). Possibly an allusion to

Alexander Pope's 1733-34 Essay on Man (I.23-28), Wheatley here may

also be referencing contemporary scientific thought about the plurality of worlds.

The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

development of the microscope and the telescope had made great scientific

advancements possible, especially in astronomy; in the title page and

pull-out image represented here, you can see an eighteenth-century orrery--a

scientific clockwork instrument used to dramatize the motion of the planets

in the solar system (via the University of Otago). Possibly an allusion to

Alexander Pope's 1733-34 Essay on Man (I.23-28), Wheatley here may

also be referencing contemporary scientific thought about the plurality of worlds.

The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

development of the microscope and the telescope had made great scientific

advancements possible, especially in astronomy; in the title page and

pull-out image represented here, you can see an eighteenth-century orrery--a

scientific clockwork instrument used to dramatize the motion of the planets

in the solar system (via the University of Otago). Possibly an allusion to

Alexander Pope's 1733-34 Essay on Man (I.23-28), Wheatley here may

also be referencing contemporary scientific thought about the plurality of worlds.

The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

development of the microscope and the telescope had made great scientific

advancements possible, especially in astronomy; in the title page and

pull-out image represented here, you can see an eighteenth-century orrery--a

scientific clockwork instrument used to dramatize the motion of the planets

in the solar system (via the University of Otago). Possibly an allusion to

Alexander Pope's 1733-34 Essay on Man (I.23-28), Wheatley here may

also be referencing contemporary scientific thought about the plurality of worlds._deign

According to the Oxford English Dictionary deign means "to think

it worthy of oneself" or "to think fit" (n.1a). Today, it typically has a

negative connotation, though it does not here.

_Ethiop

According to the OED, the word Ethiop would have been used during

Wheatley's time most often to refer to "[a] black or dark-skinned person; a

black African," and only occasionally to the country of Ethiopia,

specifically (n.A). Included here, via the Norwich Collection at Stanford University, is a 1666 map

of Africa and the surrounding oceans, embellished with a variety of images.

According to the OED, the word Ethiop would have been used during

Wheatley's time most often to refer to "[a] black or dark-skinned person; a

black African," and only occasionally to the country of Ethiopia,

specifically (n.A). Included here, via the Norwich Collection at Stanford University, is a 1666 map

of Africa and the surrounding oceans, embellished with a variety of images.

According to the OED, the word Ethiop would have been used during

Wheatley's time most often to refer to "[a] black or dark-skinned person; a

black African," and only occasionally to the country of Ethiopia,

specifically (n.A). Included here, via the Norwich Collection at Stanford University, is a 1666 map

of Africa and the surrounding oceans, embellished with a variety of images.

According to the OED, the word Ethiop would have been used during

Wheatley's time most often to refer to "[a] black or dark-skinned person; a

black African," and only occasionally to the country of Ethiopia,

specifically (n.A). Included here, via the Norwich Collection at Stanford University, is a 1666 map

of Africa and the surrounding oceans, embellished with a variety of images.

_perditionIn theological discussion, the word perdition means "the

state of final spiritual ruin or damnation; the consignment of the

unredeemed or wicked and impenitent soul to hell; the fate of those in hell;

eternal death" (OED, "perdition" n.2a). In more general terms, it suggests

ruin or degradation (n.1a).