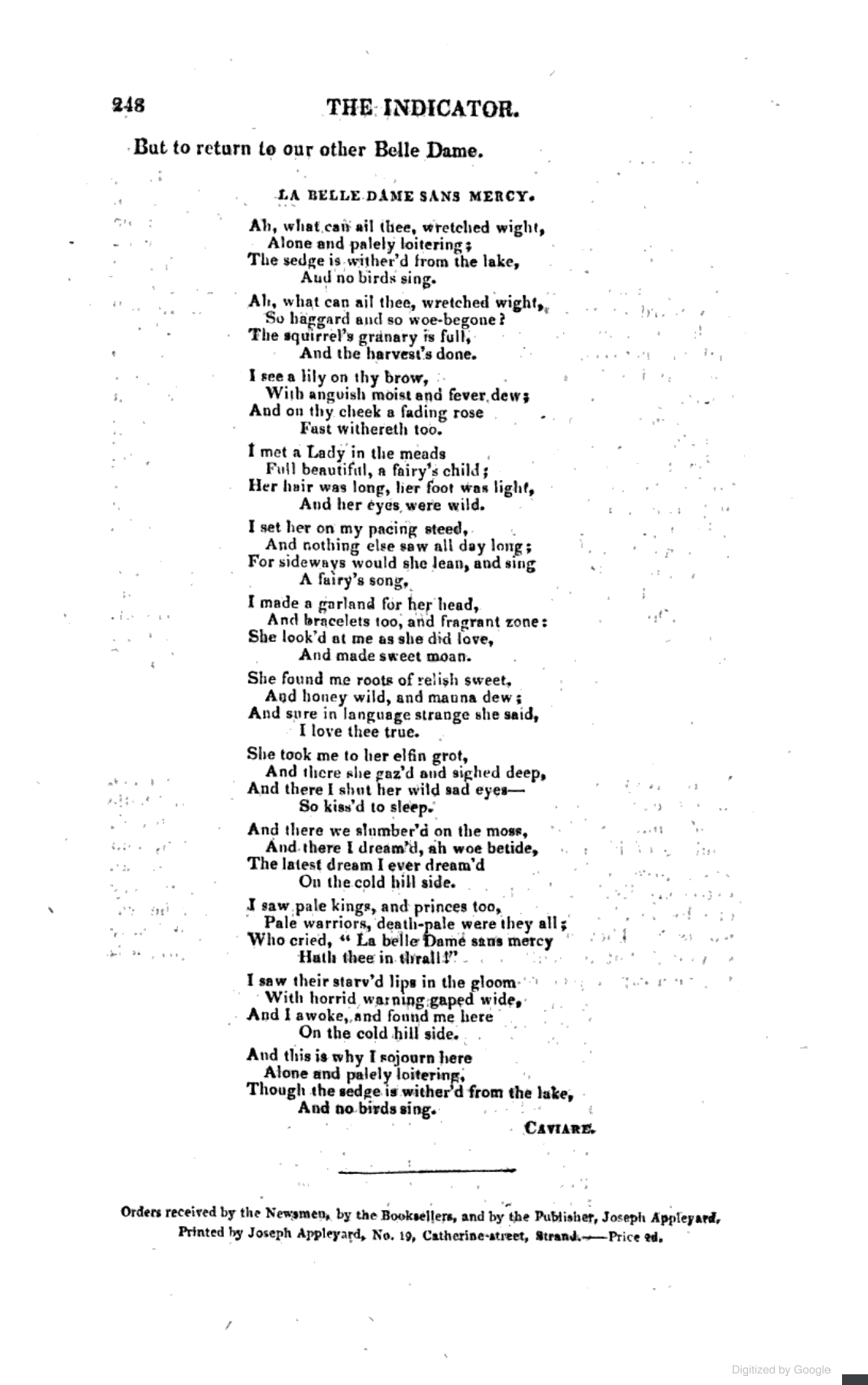

"La Belle Dame Sans Mercy"

By

John Keats

Among the pieces printed at the end of Chaucer's works, and attributed to him, is a translation, under this title, of a poem of the celebrated Alain Chartier, Secretary to Charles the Sixth and Seventh. It was the title which suggested to a friend the verses at the end of our present number. We wish Alain could have seen them. He would have found a Troubadour air for them, and sung them to La Belle Dame Agnes Sorel, who was however not Sans Mercy. The union of the imaginative and the real is very striking throughout, particularly in the dream. The wild gentleness of the rest of the thoughts and of the music are alike old; and they are also alike young; for love and imagination are always young, let them bring with them what times and accompanimenets they may. If we take real flesh and blood with us, we may throw ourselves, on the facile wings of our sympathy, into what age we please. It is only by trying to feel, as well as to fancy, through the medium of a costume, that writers become mere fleshless masks and cloaks,--things like the trophies of the ancients, when they hung up the empty armour of an enemy. A hopeless lover will still feel these verses, in spit of the introduction of something unearthly. Indeed any lover, truly touched, or any body capable of being so, will feel them; because love itself resembles a visitation; and the kindest looks, which bring with them an inevitable portion of happiness because they seem happy themselves, haunt us with a spell-like power, which makes us shudder to guess at the sufferings of those who can be fascinated by unkind ones.

People however heed not be much alarmed at the thought of such sufferings now-a-days; not at least in some countries. Since the time when ladies, and cavaliers, and poets, and lovers of nature, felt tht humanity was a high and not a mean thing, love in general has become either a grossness or a formality. The modern systems of morals would ostensibly divide women into two classes, those who have no charity, and those who have no restraint; while men,