"La Belle Dame Sans Mercy"

By

John Keats

Among the pieces printed at the end of Chaucer's works, and attributed to him, is a translation, under this title, of a poem of the celebrated Alain Chartier, Secretary to Charles the Sixth and Seventh. It was the title which suggested to a friend the verses at the end of our present number. We wish Alain could have seen them. He would have found a Troubadour air for them, and sung them to La Belle Dame Agnes Sorel, who was however not Sans Mercy. The union of the imaginative and the real is very striking throughout, particularly in the dream. The wild gentleness of the rest of the thoughts and of the music are alike old; and they are also alike young; for love and imagination are always young, let them bring with them what times and accompanimenets they may. If we take real flesh and blood with us, we may throw ourselves, on the facile wings of our sympathy, into what age we please. It is only by trying to feel, as well as to fancy, through the medium of a costume, that writers become mere fleshless masks and cloaks,--things like the trophies of the ancients, when they hung up the empty armour of an enemy. A hopeless lover will still feel these verses, in spit of the introduction of something unearthly. Indeed any lover, truly touched, or any body capable of being so, will feel them; because love itself resembles a visitation; and the kindest looks, which bring with them an inevitable portion of happiness because they seem happy themselves, haunt us with a spell-like power, which makes us shudder to guess at the sufferings of those who can be fascinated by unkind ones.

People however heed not be much alarmed at the thought of such sufferings now-a-days; not at least in some countries. Since the time when ladies, and cavaliers, and poets, and lovers of nature, felt tht humanity was a high and not a mean thing, love in general has become either a grossness or a formality. The modern systems of morals would ostensibly divide women into two classes, those who have no charity, and those who have no restraint; while men, 247 poorly conversant with the latter, and rendered indifferent to the former, aquire bad ideas of both. Instead of the worship of Love, we have the worship of Mammon; and all the difference we can see between the sufferings attending on either is, that the sufferings from the worship of Love exalt and humanize us, and those from the worship of Mammon debase and brutalize. Between the delights htere is no comparison.--Still our uneasiness keeps our knowledge going on.

A word or two more of Alain Chartier's poem. "Mr. Aleyn," saith the argument, "secretary to the king of France, framed this dialogue between a gentleman and a gentlewoman, who finding no mercy at her hand, dieth for sorrow." We know not in what year Chartier was born; but he must have lived to a good age, and written this poem in his youth, if Chaucer translated it; for he died in 1449, and Chaucer, an old man, in 1400. The beginning however, as well as the goodness of the version, looks as if our countryman had done it; for he speaks of the translations having been enjoined him by way of penance; and the Legend of Good Women was the result of a similar injunction, in consequence of his having written some stories not so much to the credit of the sex! He,--who aas he represents, had written infinite things in their praise! But the Court-ladies, it seems, did not relish the story of Troilus and Cressida. The exordium, which the translator has added, is quite in our poet's manner. He says, that he rose one day, not well awaked; and thinking how he should bet enter upon his task, he took one of his morning walks,

Till I came to a lusty green valley Full of flowers, to see a great pleasaunce; And so, boldly, (with theier benign sufferance Which read this book, touching this mattere) Thus I began, if it please you to hear.Master Aleyn's dialogue, which is very long, will not have much interest except for those who are in the situation of his lover and belle Dame; but his introduction of it, his account of his riding abroad, thinking of his lost mistress,--his hearing music in a garden, and being pressed by some friends who saw him to come in,--is all extremely lively and natural. At his entrance, the ladies, "every one by one," bade him welcome "a great deal more than he was worthy." They are waited upon, at their repast, not by "deadly servants," but by gentlemen and lovers; of one of whom he proceeds to give a capital picture.

Emong all other, one I gan espy, Which in great thought ful often came and went, As one that had been ravished utterly: In his language not greatly diligent, His countenance he kept with great torment, But his desire farre passesd his reason, For ever his eye went after his entent, Full many a time, when it was no season. To make chere, sore himselfe he pained, And outwardly he fained great gladnesse: To sing also, by force he was constrained, For no pleasaunce, but very shamefastness; For the complaint of his most heavinesse Came to his voice. 248But to return to our other Belle Dame.

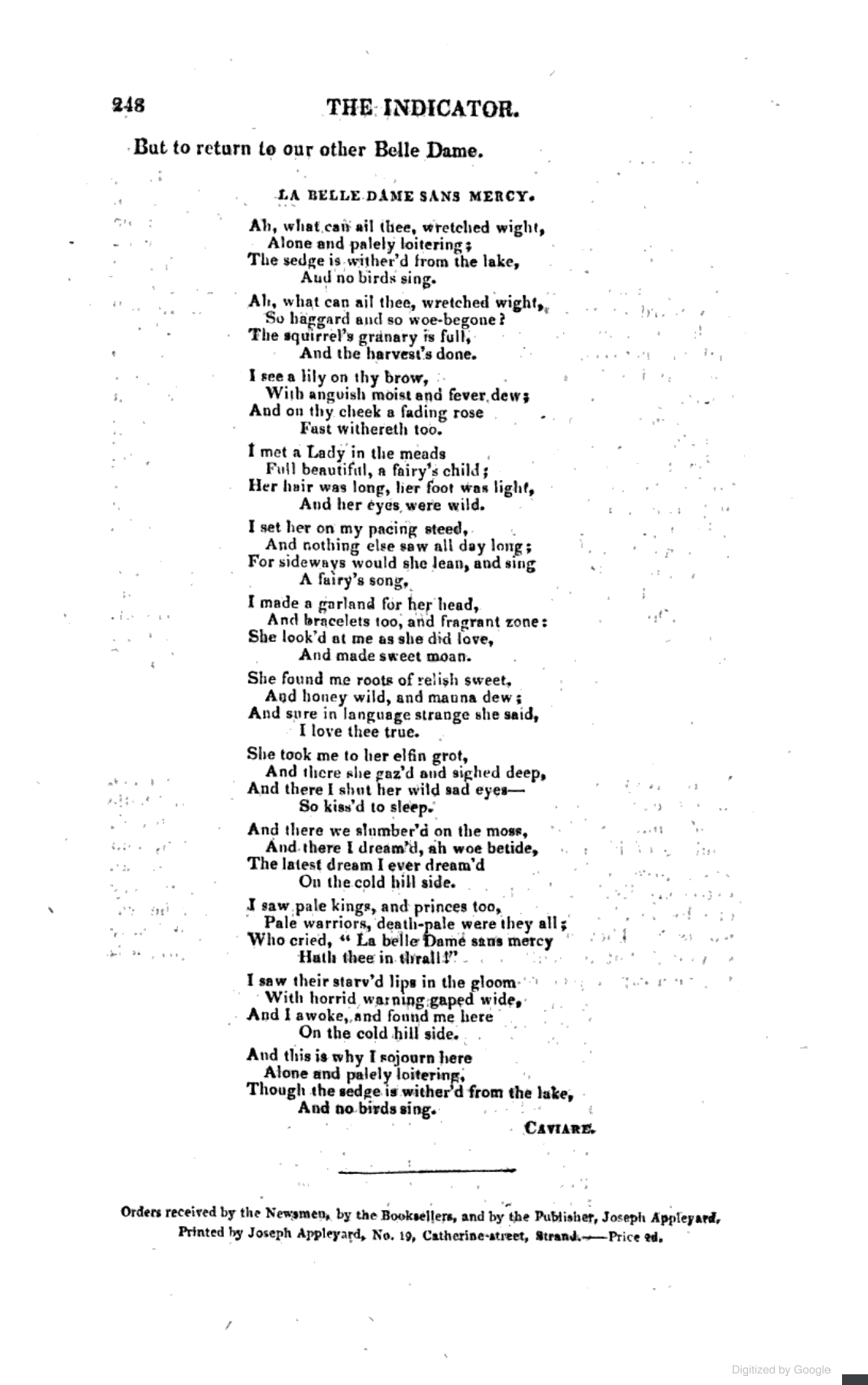

LA BELLE DAME SANS MERCY.1Ah, what can ail thee, wretched wight, 2Alone and palely loitering; 3The sedge has wither'd from the lake, 4And no birds sing. 5O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms, 6So haggard and so woe-begone? 7The squirrel's granary is full, 8And the harvest's done. 9I see a lily on thy brow, 10With anguish moist and fever dew, 11And on thy cheeks a fading rose 12Fast withereth too. 13I met a lady in the meads, 14Full beautiful — a fairy's child, 15Her hair was long, her foot was light, 16And her eyes were wild. 17I set her on my pacing steed, 18And nothing else saw all day long, 19For sidelong would she lean, and sing 20A fairy's song. 21I made a garland for her head, 22And bracelets too, and fragrant zone; 23She look'd at me as she did love, 24And made sweet moan. 25She found me roots of relish sweet, 26And honey wild, and manna dew, 27And sure in language strange she said — 28I love thee true. 29She took me to her elfin grot, 30And there she wept, and sigh'd full sore, 31And there I shut her wild wild eyes 32So kiss'd to sleep. 33And there we slumber'd on the moss 34And there I dream'd, ah woe betide, 35The latest dream I ever dream'd 36On the cold hill side. 37I saw pale kings and princes too, 38Pale warriors, death-pale were they all; 39They cried — "La belle Dame sans mercy 40Hath thee in thrall!" 41I saw their starv'd lips in the gloam, 42With horrid warning gaped wide, 43And I awoke and found me here, 44On the cold hill side. 45And this is why I sojourn here, 46Alone and paleley loitering. 47Though the sedge has wither'd from the lake, 48And no birds sing.