Fantomina; or, Love in a Maze

By

Eliza Haywood

Transcription, correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Students and Staff of Marymount University

secret_historyWhile there are many critical

understandings of the secret history in literature, as the essays in The Secret History in Literature: 1660-1820

(2017) suggest, the genre usually offers a glimpse into the secret

lives of public individuals. In the amatory tradition of Fantomina, this "private" side is typically filled with sexual or

political intrigue. - [TH]author

Source: Engraved portrait of Haywood Eliza Haywood (c.1693-1756) was a

prolific author, actor, and publisher of the early- to mid-eighteenth century. She

is most famous, today, for her novels and novellas, among which Fantominais numbered. The image included here, via

Wikimedia Commons, is an engraved frontispiece portrait by George Vertue.

Haywood wrote in a number of different genres, including amatory fiction, domestic

fiction, and essay. - [TH]wallerThis epigraph is composed of the last

couplet from "To A. H: Of the Different Successe of Their Loves," a poem by Edmund

Waller (1606-1687). Waller's poem, published in 1645, takes a

Petrarchan perspective of the relationship between the male lover and the

female beloved. This couplet was oft-quoted during the period, and features in

George Etheredge's Restoration comedy Man of Mode, where

it is spoken by the protagonist Dorimant. Read more about Waller at Encyclopaedia Britannica. - [TH]box

Source: Engraved portrait of Haywood Eliza Haywood (c.1693-1756) was a

prolific author, actor, and publisher of the early- to mid-eighteenth century. She

is most famous, today, for her novels and novellas, among which Fantominais numbered. The image included here, via

Wikimedia Commons, is an engraved frontispiece portrait by George Vertue.

Haywood wrote in a number of different genres, including amatory fiction, domestic

fiction, and essay. - [TH]wallerThis epigraph is composed of the last

couplet from "To A. H: Of the Different Successe of Their Loves," a poem by Edmund

Waller (1606-1687). Waller's poem, published in 1645, takes a

Petrarchan perspective of the relationship between the male lover and the

female beloved. This couplet was oft-quoted during the period, and features in

George Etheredge's Restoration comedy Man of Mode, where

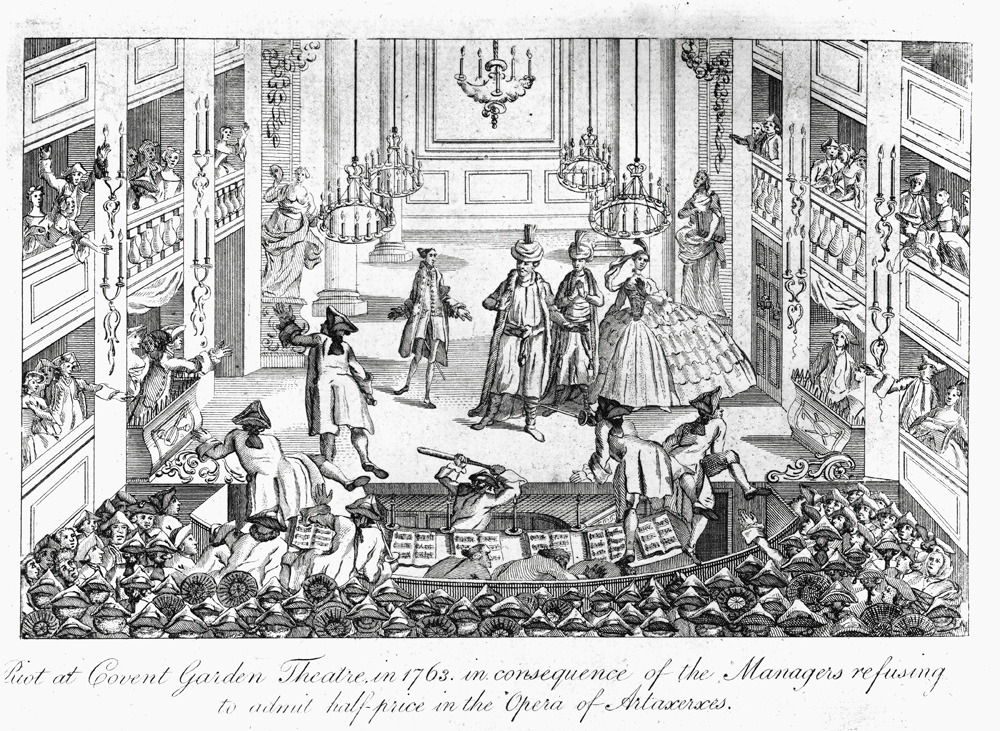

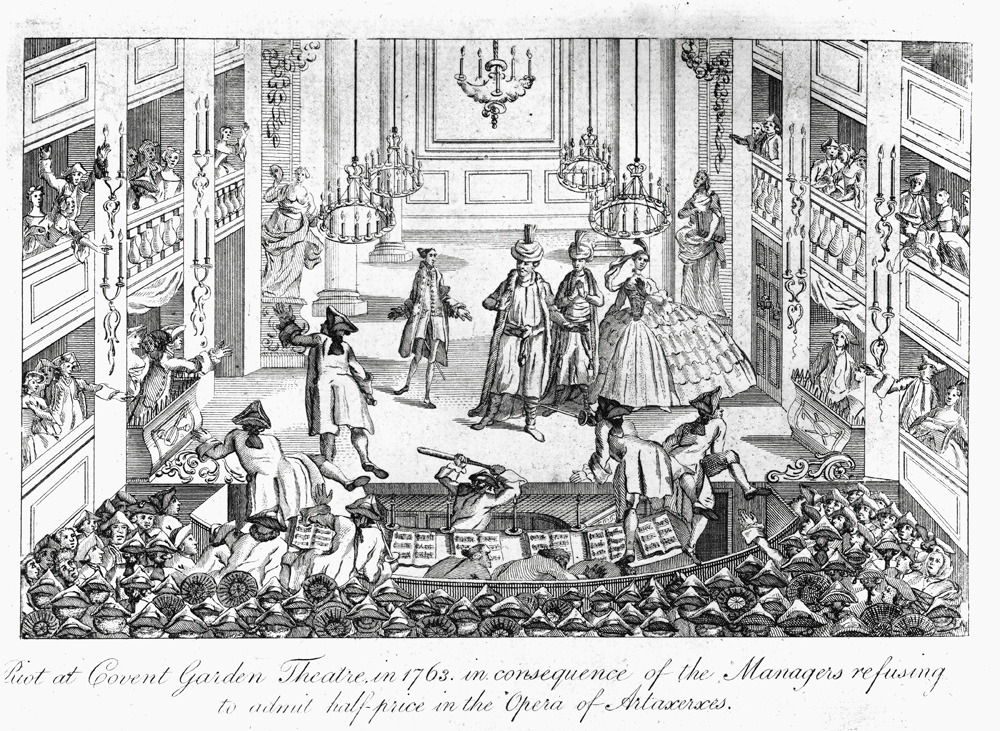

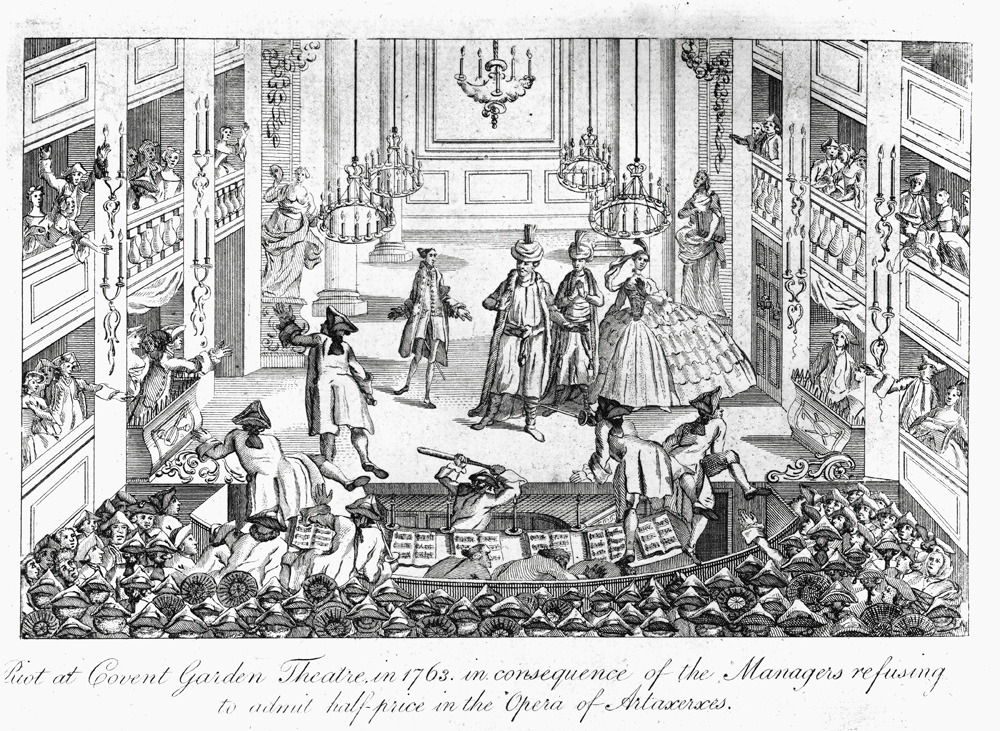

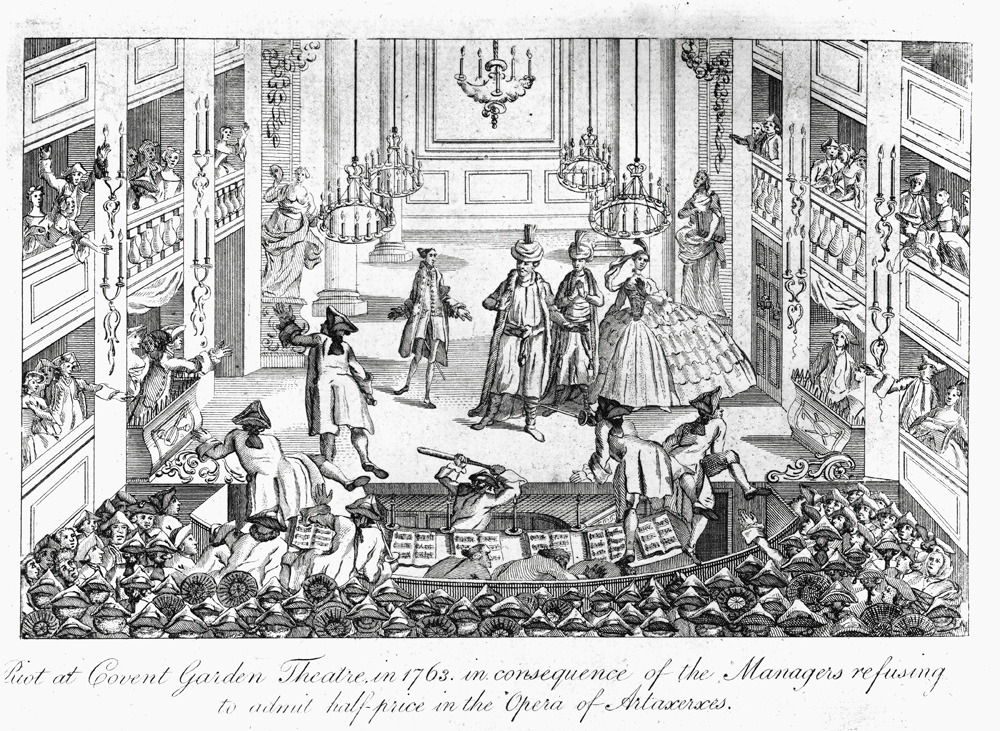

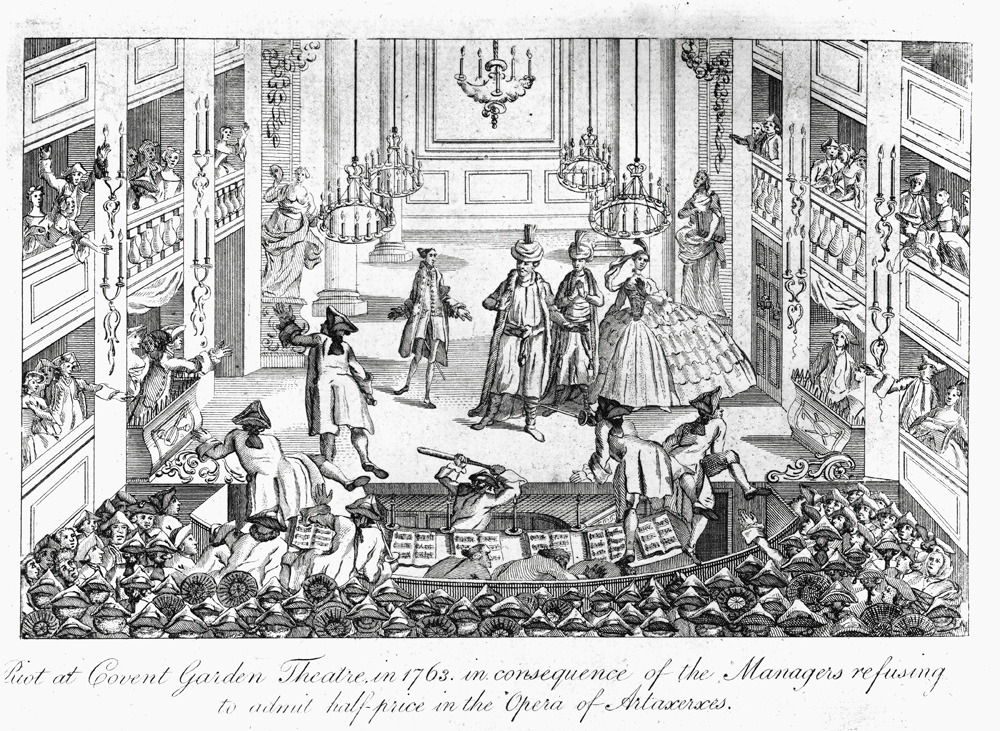

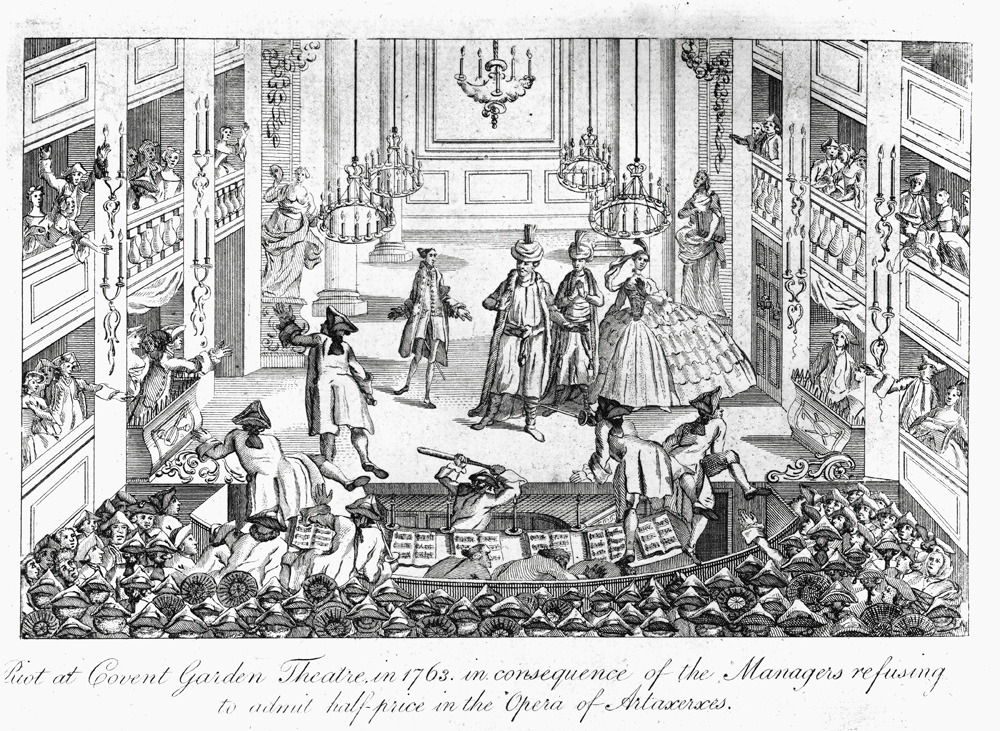

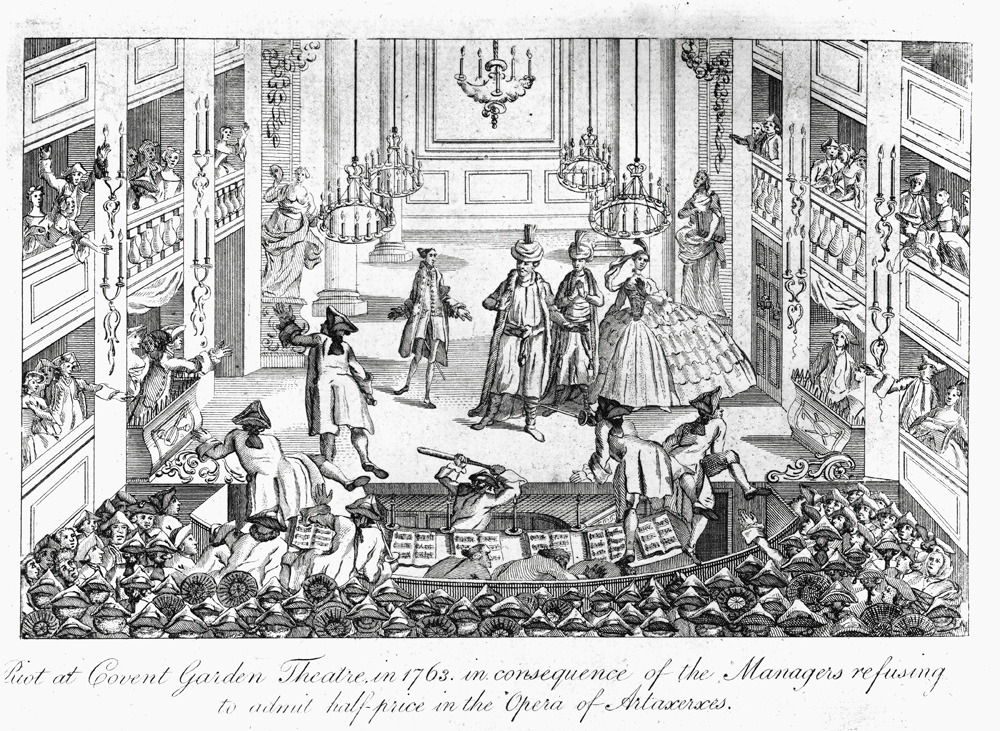

it is spoken by the protagonist Dorimant. Read more about Waller at Encyclopaedia Britannica. - [TH]box Source: Engraving depicting a riot at Covent Garden TheatrePlayhouses

during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in England organized seating

according to price and social status. Boxes were the most expensive of seating

areas, and could hold several people in style. The image included here, from

the Victoria and Albert Museum, depicts a famous riot at Covent Garden

theater during a performance of the opera Artaxerxes in

1763. For more information about the development of theater in the eighteenth

century, see Andrew Dickson's introduction at the British Library. - [TH]toastsAccording to the OED, a

"toast" is a "[a] lady who is named as the person to whom a company is requested

to drink; often one who is the reigning belle of the season" (n2.1). - [TH]pitThe "pit" was a

mixed-sex seating area in the eighteenth-century, notable for its energy and

activity. According to The Oxford Companion to Theatre and

Performance, the "pit occupied the floor of the theatre at a lower level

than the stage and, unlike the standing pit of earlier public theatres, contained

rows of backless benches set on a raked floor. Seats in the pit were half the

price of a seat in the box and attracted a mixed audience of men and women. The

activity of the audience in the pit and the behaviour of the occupants of the

boxes, especially with the King present, were part of the theatregoing spectacle."

Prostitutes, wits, and rakes frequented the pit and the middle galleries. For more

information, see Douglas Canfield's introduction to The Broadview Anthology

of Restoration and Early Eighteenth-Century Drama

(vxiii). - [TH]hoodsThroughout

the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, hoods and

hooded cloaks were both practical and fashionable garments for women. In

the winter, hoods and masks protected the body from icy air, and they generally

allowed women more freedom to move un-seen throughout the city, as described in

this article from the BBC's History

Magazine. - [TH]galleryThe gallery-box or middle

gallery is a seating area in cost between pit and box seats. Servants often sat in

the inexpensive upper gallery seats. When Fantomina goes again tho the playhouse

on her "frolick," she sits in the gallery areas that signify her sexual

availability. Often, sex workers found partners and keepers at the playhouse,

earning the theater a reputation for sexual display. - [TH]beauplaisirBeauplaisir is a French portmanteau word meaning "beautiful pleasure." Beau was

also a generic term in the eighteenth century for a lady's suitor or sweetheart,

according to the OED. - [TH]drawing_roomThe drawing or "withdrawing" room was a room in the home of

a wealthier class of people to which women would "withdraw" after dinner, to brew

tea and converse. Later, the male contingent would join the women in the drawing

room for polite conversation and mingling. For more information on the history and

evolution of the drawing room, see this review of Jeremy Musson's Drawing

Room. - [TH]salutationsSalutations refer to

customary greetings. - [TH]genteelUsed here as an

adjective, "genteel" refers to a quality of polite refinement thought to be

possessed by those of the gentry class. According to this review of Peter

Cross's The Origins of the English Gentry, the gentry

class is "a type of lesser nobility, based on landholding," that often

dispensed justice in the locality and wielded great social power. - [TH]railleryAccording to the OED, raillery refers to "[g]ood-humoured ridicule or banter,"

which can sometimes be more satirical or mocking. - [TH]quality"Quality" is a difficult concept to grasp;

in the eighteenth century, it typically referred to rank or social position, and

more particularly, noble or high social position, as indicated by senses 4 and 5

in the OED. - [TH]chairA hackney or sedan chair was a hireable mode of

transportation that consisted of a single enclosed seat carried, on poles, by two

strong men. It was small enough to enter into the front doors of a well-appointed

house, thus ensuring secresy. Read more about the hackney or sedan chair in this article from Bath Magazine. The image

included here shows an early eighteenth-century French sedan chair, without the

horizontal carrying poles, housed

in the VAM.

Source: Engraving depicting a riot at Covent Garden TheatrePlayhouses

during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in England organized seating

according to price and social status. Boxes were the most expensive of seating

areas, and could hold several people in style. The image included here, from

the Victoria and Albert Museum, depicts a famous riot at Covent Garden

theater during a performance of the opera Artaxerxes in

1763. For more information about the development of theater in the eighteenth

century, see Andrew Dickson's introduction at the British Library. - [TH]toastsAccording to the OED, a

"toast" is a "[a] lady who is named as the person to whom a company is requested

to drink; often one who is the reigning belle of the season" (n2.1). - [TH]pitThe "pit" was a

mixed-sex seating area in the eighteenth-century, notable for its energy and

activity. According to The Oxford Companion to Theatre and

Performance, the "pit occupied the floor of the theatre at a lower level

than the stage and, unlike the standing pit of earlier public theatres, contained

rows of backless benches set on a raked floor. Seats in the pit were half the

price of a seat in the box and attracted a mixed audience of men and women. The

activity of the audience in the pit and the behaviour of the occupants of the

boxes, especially with the King present, were part of the theatregoing spectacle."

Prostitutes, wits, and rakes frequented the pit and the middle galleries. For more

information, see Douglas Canfield's introduction to The Broadview Anthology

of Restoration and Early Eighteenth-Century Drama

(vxiii). - [TH]hoodsThroughout

the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, hoods and

hooded cloaks were both practical and fashionable garments for women. In

the winter, hoods and masks protected the body from icy air, and they generally

allowed women more freedom to move un-seen throughout the city, as described in

this article from the BBC's History

Magazine. - [TH]galleryThe gallery-box or middle

gallery is a seating area in cost between pit and box seats. Servants often sat in

the inexpensive upper gallery seats. When Fantomina goes again tho the playhouse

on her "frolick," she sits in the gallery areas that signify her sexual

availability. Often, sex workers found partners and keepers at the playhouse,

earning the theater a reputation for sexual display. - [TH]beauplaisirBeauplaisir is a French portmanteau word meaning "beautiful pleasure." Beau was

also a generic term in the eighteenth century for a lady's suitor or sweetheart,

according to the OED. - [TH]drawing_roomThe drawing or "withdrawing" room was a room in the home of

a wealthier class of people to which women would "withdraw" after dinner, to brew

tea and converse. Later, the male contingent would join the women in the drawing

room for polite conversation and mingling. For more information on the history and

evolution of the drawing room, see this review of Jeremy Musson's Drawing

Room. - [TH]salutationsSalutations refer to

customary greetings. - [TH]genteelUsed here as an

adjective, "genteel" refers to a quality of polite refinement thought to be

possessed by those of the gentry class. According to this review of Peter

Cross's The Origins of the English Gentry, the gentry

class is "a type of lesser nobility, based on landholding," that often

dispensed justice in the locality and wielded great social power. - [TH]railleryAccording to the OED, raillery refers to "[g]ood-humoured ridicule or banter,"

which can sometimes be more satirical or mocking. - [TH]quality"Quality" is a difficult concept to grasp;

in the eighteenth century, it typically referred to rank or social position, and

more particularly, noble or high social position, as indicated by senses 4 and 5

in the OED. - [TH]chairA hackney or sedan chair was a hireable mode of

transportation that consisted of a single enclosed seat carried, on poles, by two

strong men. It was small enough to enter into the front doors of a well-appointed

house, thus ensuring secresy. Read more about the hackney or sedan chair in this article from Bath Magazine. The image

included here shows an early eighteenth-century French sedan chair, without the

horizontal carrying poles, housed

in the VAM. Source: Early 18th-century French sedan chair (VAM) - [TH]cogitations"Cogitations" are thoughts; often, the word contains a humourously exaggerated

connotation. - [TH]devoirsFrom the French word for duty, "devoirs" are

dutiful addresses paid to someone out of respect or courtesy. See sense 4 in the

OED. - [TH]lodgingsFantomina explains that she rented rooms near the playhouse, which were centrally

located and more expensive than houses or rooms in houses further afield. She

would likely have rented the furnished first floor for between 2 and 4 guineas per

week, according to John Trusler's late eighteenth-century London Adviser and

Guide. For a sense of the cost of living in the period, see "Currency, Coinage

and the Cost of Living" at the Old Bailey Online. For a good overview of

early Georgian town houses, see this Google

Arts and Culture Spotter's Guide. - [TH]collationA "collation," according to the OED, is a light, often cold

meal of meats, fruits, and wine that has little to no need of preparation. - [TH]houseWhen renting furnished rooms, a lodger might bring their own

servant or use the servants who work consistently at the house. Here, we learn

that Fantomina did not bring her own servant, but drew on the services of those

from whom she rented. - [TH]honourHonor, in this sense, is being used to refer to Fantomina's

"virtue as regards sexual morality," according to sense 7 in the OED--or, "a

reputation for this, one's good name." - [TH]countryA country gentleman would

be a member of the landed gentry, residing most likely in a country house or

mansion where the business of the locality was often conducted. The country

gentleman would likely have also had a town house in London. To read more about

the country house, see Mark Girouard's Life in the English Country House: A Social and Architectural

History (1978). - [TH]pieceA broad

piece is a coin approximately the same as a pound, worth 20 shillings. It was

called a "broad piece" because it was thicker and and bigger than newer coins,

minted after 1663. See "A Note on British

Money", included in the Broadview edition of Anti-Pamela and

Shamela (50ff). - [TH]barge

Source: Early 18th-century French sedan chair (VAM) - [TH]cogitations"Cogitations" are thoughts; often, the word contains a humourously exaggerated

connotation. - [TH]devoirsFrom the French word for duty, "devoirs" are

dutiful addresses paid to someone out of respect or courtesy. See sense 4 in the

OED. - [TH]lodgingsFantomina explains that she rented rooms near the playhouse, which were centrally

located and more expensive than houses or rooms in houses further afield. She

would likely have rented the furnished first floor for between 2 and 4 guineas per

week, according to John Trusler's late eighteenth-century London Adviser and

Guide. For a sense of the cost of living in the period, see "Currency, Coinage

and the Cost of Living" at the Old Bailey Online. For a good overview of

early Georgian town houses, see this Google

Arts and Culture Spotter's Guide. - [TH]collationA "collation," according to the OED, is a light, often cold

meal of meats, fruits, and wine that has little to no need of preparation. - [TH]houseWhen renting furnished rooms, a lodger might bring their own

servant or use the servants who work consistently at the house. Here, we learn

that Fantomina did not bring her own servant, but drew on the services of those

from whom she rented. - [TH]honourHonor, in this sense, is being used to refer to Fantomina's

"virtue as regards sexual morality," according to sense 7 in the OED--or, "a

reputation for this, one's good name." - [TH]countryA country gentleman would

be a member of the landed gentry, residing most likely in a country house or

mansion where the business of the locality was often conducted. The country

gentleman would likely have also had a town house in London. To read more about

the country house, see Mark Girouard's Life in the English Country House: A Social and Architectural

History (1978). - [TH]pieceA broad

piece is a coin approximately the same as a pound, worth 20 shillings. It was

called a "broad piece" because it was thicker and and bigger than newer coins,

minted after 1663. See "A Note on British

Money", included in the Broadview edition of Anti-Pamela and

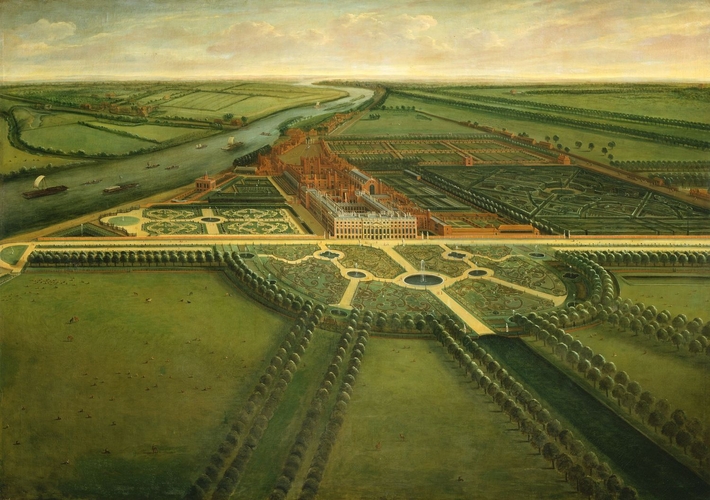

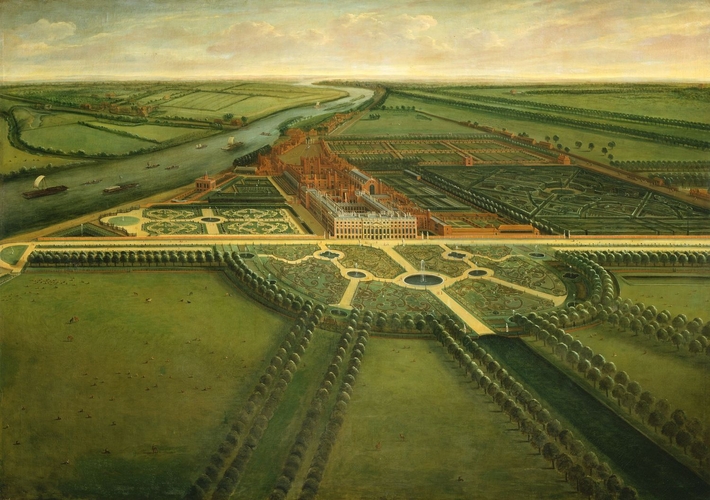

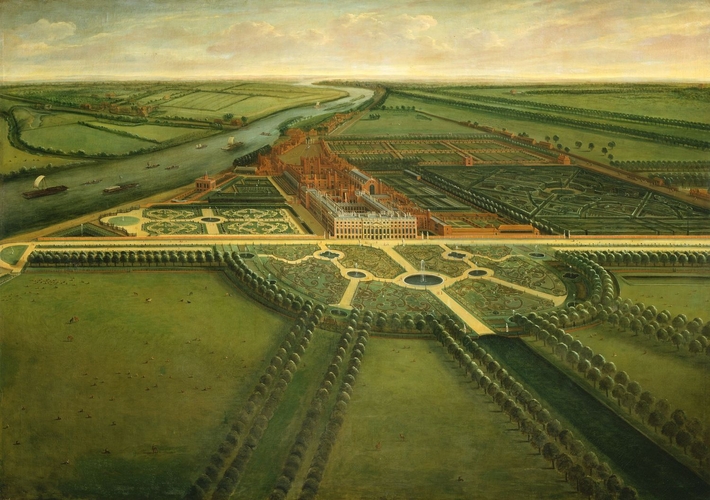

Shamela (50ff). - [TH]barge Source: https://www.rct.uk/collection/404760/a-view-of-hampton-courtThe river Thames was a

source of work, pleasure, and transportation in the eighteenth century; it

connected many significant country towns to London, and access to Hampton Court

Palace as well as the many London pleasure gardens was primarily accomplished via

the river. To

learn more about the history of the Thames, see this BBC article by Andy

Dangerfield. The image included here, an early

eighteenth-century painting by Leonard Knyff via the Royal Collection

Trust, shows Hampton Court Palace and the barges passing on the river

Thames. - [TH]intrigueAccording to the OED, an "intrigue" is at once a secret

intimacy between lovers, as well as an intricate or maze-like contrivance,

perhaps enabling the clandestine romance. - [TH]habitA habit used in this sense refers to a particular garment or

mode of dress, often specific to a profession or activity. See the OED senses 1

and 2. - [TH]chapelFantomina

here likely refers to the Chapel Royal at St. James's Palace. During the Georgian

period, the Chapel Royal became "a significant cultural centre." For more

information on the Chapel Royal, see this article by Carolyn Harris. - [TH]gardens

Source: https://www.rct.uk/collection/404760/a-view-of-hampton-courtThe river Thames was a

source of work, pleasure, and transportation in the eighteenth century; it

connected many significant country towns to London, and access to Hampton Court

Palace as well as the many London pleasure gardens was primarily accomplished via

the river. To

learn more about the history of the Thames, see this BBC article by Andy

Dangerfield. The image included here, an early

eighteenth-century painting by Leonard Knyff via the Royal Collection

Trust, shows Hampton Court Palace and the barges passing on the river

Thames. - [TH]intrigueAccording to the OED, an "intrigue" is at once a secret

intimacy between lovers, as well as an intricate or maze-like contrivance,

perhaps enabling the clandestine romance. - [TH]habitA habit used in this sense refers to a particular garment or

mode of dress, often specific to a profession or activity. See the OED senses 1

and 2. - [TH]chapelFantomina

here likely refers to the Chapel Royal at St. James's Palace. During the Georgian

period, the Chapel Royal became "a significant cultural centre." For more

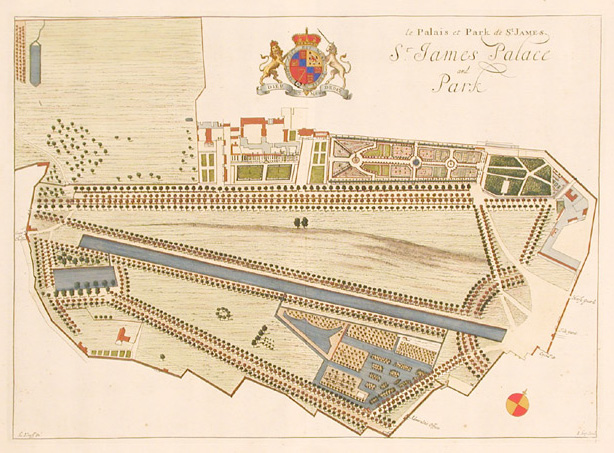

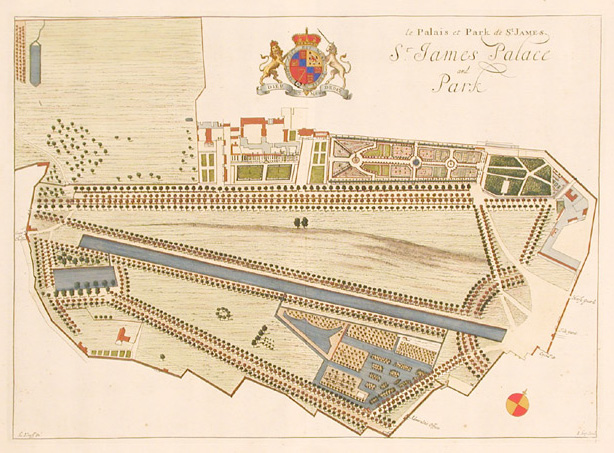

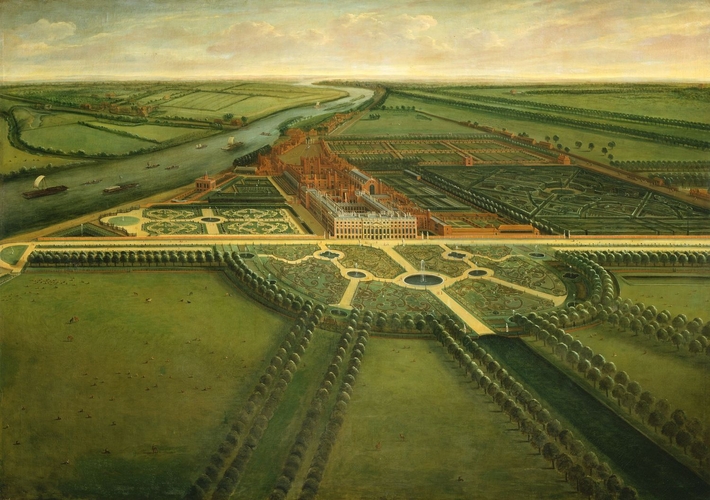

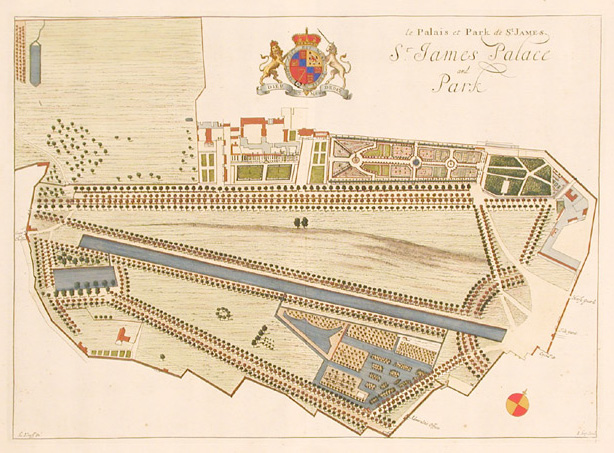

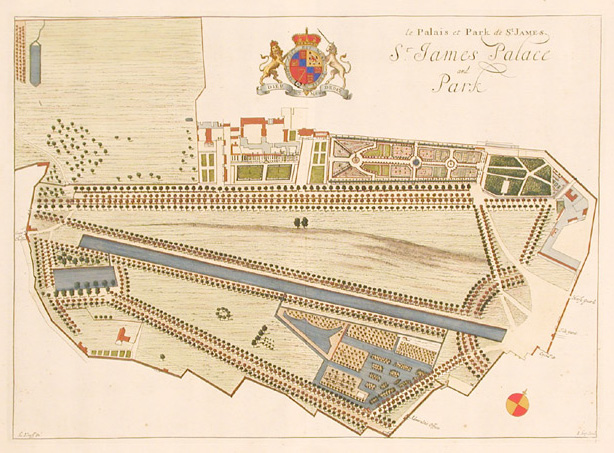

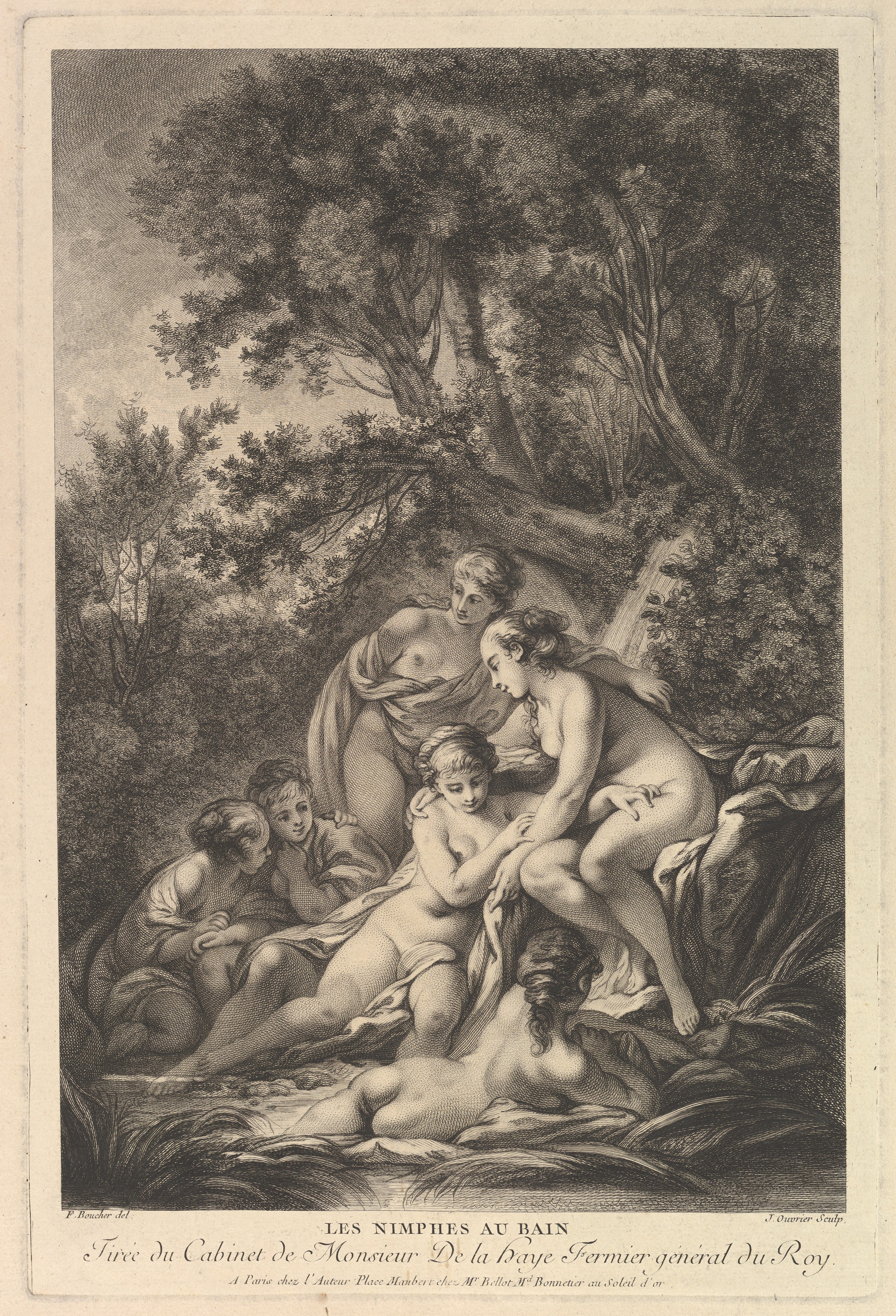

information on the Chapel Royal, see this article by Carolyn Harris. - [TH]gardens Source: Jan Kip, plan of St.James's Palace and Gardens, early 18th centuryThe

palace gardens at St. James's Palace, which was the primary royal residence until

early nineteenth century, are pictured in the bird's eye plan by Jan Kip shown

here (via Wikimedia Commons). Something of the spirit of the parks and gardens of

the period can be grasped by examining the 1745 painting of St. James's Park and the Mall, by Joseph Nickolls,

discussed here. - [TH]opera

Source: Jan Kip, plan of St.James's Palace and Gardens, early 18th centuryThe

palace gardens at St. James's Palace, which was the primary royal residence until

early nineteenth century, are pictured in the bird's eye plan by Jan Kip shown

here (via Wikimedia Commons). Something of the spirit of the parks and gardens of

the period can be grasped by examining the 1745 painting of St. James's Park and the Mall, by Joseph Nickolls,

discussed here. - [TH]opera Source: Engraving depicting a riot at Covent Garden TheatreOpera became

extraordinarily fashionable during the eighteenth century. Read more about the

history of opera during the period from the

Victoria and Albert Museum. The image included here shows a riot during

an opera at Covent Garden Theatre in 1763. - [TH]poignancyAccording to the OED,

"poingnancy" refers to the sharpness or piquancy of a feeling. - [TH]dissembleTo

"dissemble" is to disguise or feign--to appear otherwise (OED). - [TH]bathBath is a fashionable resort and thermal spa town located in

the south west of England, near Bristol. In the eighteenth century, it became a

destination and, according to the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, "one of the most beautiful cities

in Europe, with architecture and landscape combined harmoniously for the

enjoyment of the spa town’s cure takers." - [TH]wagonA wagon is a much ruder

form of transportation than the elegant coach, befitting Fantomina's new

character. Travel by stage coach from London to Bath during this period would have

taken at least two days. - [TH]cap

Source: Engraving depicting a riot at Covent Garden TheatreOpera became

extraordinarily fashionable during the eighteenth century. Read more about the

history of opera during the period from the

Victoria and Albert Museum. The image included here shows a riot during

an opera at Covent Garden Theatre in 1763. - [TH]poignancyAccording to the OED,

"poingnancy" refers to the sharpness or piquancy of a feeling. - [TH]dissembleTo

"dissemble" is to disguise or feign--to appear otherwise (OED). - [TH]bathBath is a fashionable resort and thermal spa town located in

the south west of England, near Bristol. In the eighteenth century, it became a

destination and, according to the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, "one of the most beautiful cities

in Europe, with architecture and landscape combined harmoniously for the

enjoyment of the spa town’s cure takers." - [TH]wagonA wagon is a much ruder

form of transportation than the elegant coach, befitting Fantomina's new

character. Travel by stage coach from London to Bath during this period would have

taken at least two days. - [TH]cap Source: Round-eared cap (VAM)According to The

Dictionary of Fashion History, a round-eared cap is a "white

indoor cap curving round the face to the level of the ears or below," often

ruffled, and drawn close with a string along the shallow back edge of the cap.

These caps were popular among all classes from around 1730 to 1760, making this an

early reference. The image included here, from the Victoria and Albert Museum, shows a mannequin in a quilted green

petticoat and round-eared cap. - [TH]stuff"Stuff" here

refers to a type of woven material made of worsted woollen cloth. See OED sense

5c. - [TH]maidA maidservant was one of the lowest-paid

members of a domestic household, though others--like scullery maids, who were

responsible for scrubbing kitchen pans--earned much less. A housemaid was

typically responsible for airing rooms, emptying chamber pots, cleaning and

beating rugs and beds, and so on. For more information on female domestic

servants, see Part 12

of Eighteenth-Century Women: An Anthology, Volume

21. - [TH]waters

Source: Round-eared cap (VAM)According to The

Dictionary of Fashion History, a round-eared cap is a "white

indoor cap curving round the face to the level of the ears or below," often

ruffled, and drawn close with a string along the shallow back edge of the cap.

These caps were popular among all classes from around 1730 to 1760, making this an

early reference. The image included here, from the Victoria and Albert Museum, shows a mannequin in a quilted green

petticoat and round-eared cap. - [TH]stuff"Stuff" here

refers to a type of woven material made of worsted woollen cloth. See OED sense

5c. - [TH]maidA maidservant was one of the lowest-paid

members of a domestic household, though others--like scullery maids, who were

responsible for scrubbing kitchen pans--earned much less. A housemaid was

typically responsible for airing rooms, emptying chamber pots, cleaning and

beating rugs and beds, and so on. For more information on female domestic

servants, see Part 12

of Eighteenth-Century Women: An Anthology, Volume

21. - [TH]waters Source: Rowlandson, 'The Comforts of Bath' (1798)Througout the

eighteenth century, Bath--known for its thermal springs--became a fashionable

place to relax and "take the waters." Thomas Rowlandson's satirical 1798 watercolor, "The Comforts of Bath: The Pump

Room," included here via Wikimedia Commons, depicts patients suffering

from a variety of illnesses descending on the Pump Room to drink the hot mineral

spring waters. It was believed that the mineral spring waters had curative

properties, though many people went to Bath for relaxation and leisure in

general. - [TH]celiaCelia is a generic pastoral female name. - [TH]service"Service" in this sense

refers to the position of domestic servitude she has acquired (OED). - [TH]mourning_

Source: Rowlandson, 'The Comforts of Bath' (1798)Througout the

eighteenth century, Bath--known for its thermal springs--became a fashionable

place to relax and "take the waters." Thomas Rowlandson's satirical 1798 watercolor, "The Comforts of Bath: The Pump

Room," included here via Wikimedia Commons, depicts patients suffering

from a variety of illnesses descending on the Pump Room to drink the hot mineral

spring waters. It was believed that the mineral spring waters had curative

properties, though many people went to Bath for relaxation and leisure in

general. - [TH]celiaCelia is a generic pastoral female name. - [TH]service"Service" in this sense

refers to the position of domestic servitude she has acquired (OED). - [TH]mourning_ Source: Portrait of a widow in mourning garbIn this enamel miniature portrait c.1710, via Philip

Mould and Company, the artist

Christian Zincke has depicted Henrietta Maria, Lady Ashburnham, in first

mourning for her husband; Henrietta Maria is twenty-three in this

portrait. First or deep mourning lasted approximately three months after

the death of a spouse, during which time the mourner wore non-reflective black

fabrics like bombazine. - [TH]pinnersA pinner is, according to

the OED, a cap with long flaps on either side that fits more tightly around the

head; it is often worn by women of higher social standing. "Pinners" also refers

to the flaps on either side of the cap. - [TH]bristolBristol is a port town about 15 miles

west of Bath. - [TH]ephesian_matronIn the story of the Ephesian matron, first

told in Petronius' Satyricon, a new widow in deep mourning

for her husband and known for her chastity is seduced by a soldier tasked with

guarding the crucified bodies of three theives. While the soldier and the

beautiful young widow are otherwise employed, one of the bodies disappears, and to

save her lover, the widow replaces the missing thief with her husband's corpse.

This story was adapted in the seventeenth century by Jean de La Fontaine. Read

more about this story and the seventeenth-century adaptation that Haywood would

have known of in Robert

Colton's article, "The Story of the Widow of Ephesus in Petronius and La

Fontaine."

- [TH]narratorWhile

"Fantomina" appears to be told in the third person omniscient, there is a

first-person narrator who interjects at points with her own thoughts, as she does

here. - [TH]billetA "billet" is the French

word for letter; a billet doux is a love letter. - [TH]hand"Hand" here refers to the

style of handwriting used in the letter. - [TH]gallGall is another word for

bile; figuratively, it refers to bitterness, a feature of bile. - [TH]nymph

Source: Portrait of a widow in mourning garbIn this enamel miniature portrait c.1710, via Philip

Mould and Company, the artist

Christian Zincke has depicted Henrietta Maria, Lady Ashburnham, in first

mourning for her husband; Henrietta Maria is twenty-three in this

portrait. First or deep mourning lasted approximately three months after

the death of a spouse, during which time the mourner wore non-reflective black

fabrics like bombazine. - [TH]pinnersA pinner is, according to

the OED, a cap with long flaps on either side that fits more tightly around the

head; it is often worn by women of higher social standing. "Pinners" also refers

to the flaps on either side of the cap. - [TH]bristolBristol is a port town about 15 miles

west of Bath. - [TH]ephesian_matronIn the story of the Ephesian matron, first

told in Petronius' Satyricon, a new widow in deep mourning

for her husband and known for her chastity is seduced by a soldier tasked with

guarding the crucified bodies of three theives. While the soldier and the

beautiful young widow are otherwise employed, one of the bodies disappears, and to

save her lover, the widow replaces the missing thief with her husband's corpse.

This story was adapted in the seventeenth century by Jean de La Fontaine. Read

more about this story and the seventeenth-century adaptation that Haywood would

have known of in Robert

Colton's article, "The Story of the Widow of Ephesus in Petronius and La

Fontaine."

- [TH]narratorWhile

"Fantomina" appears to be told in the third person omniscient, there is a

first-person narrator who interjects at points with her own thoughts, as she does

here. - [TH]billetA "billet" is the French

word for letter; a billet doux is a love letter. - [TH]hand"Hand" here refers to the

style of handwriting used in the letter. - [TH]gallGall is another word for

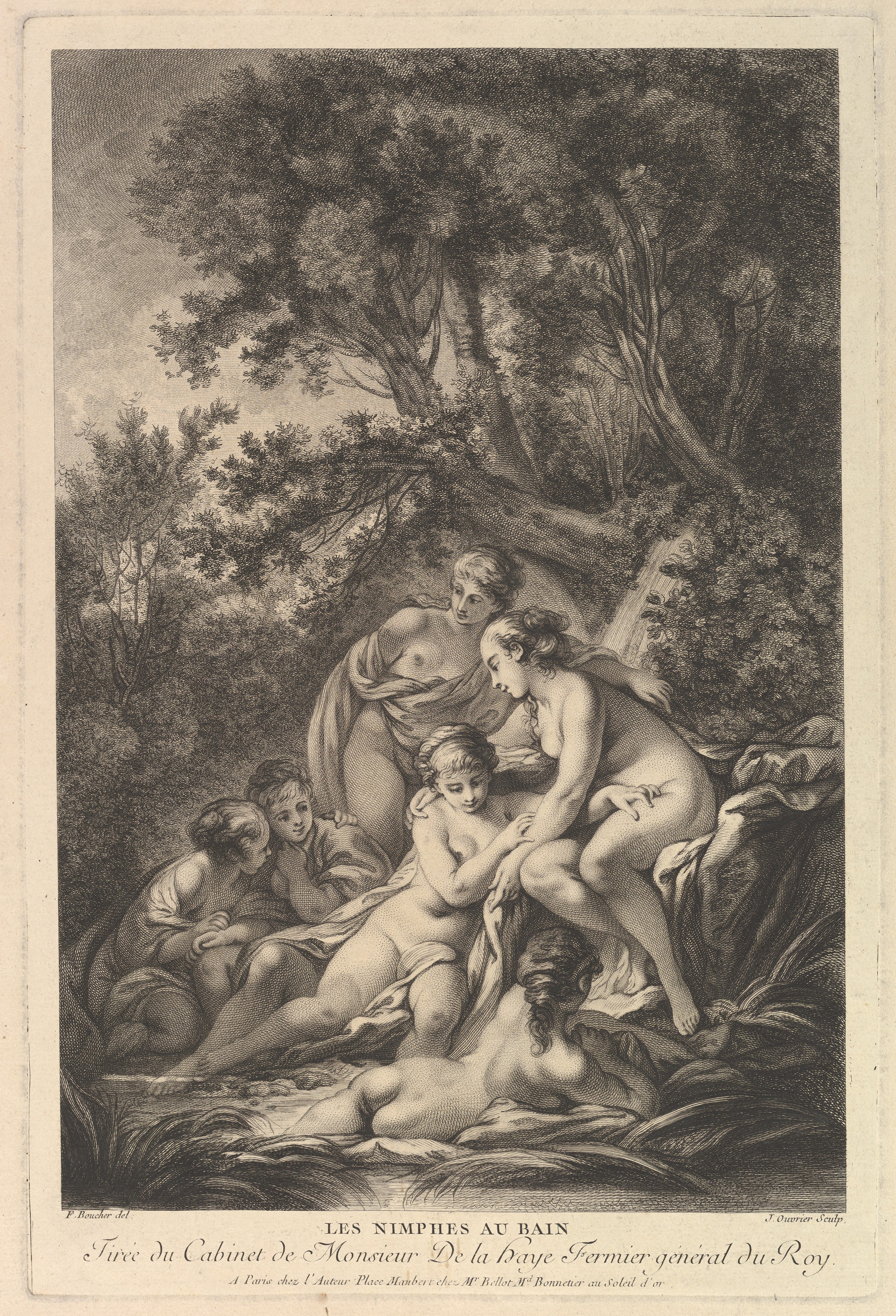

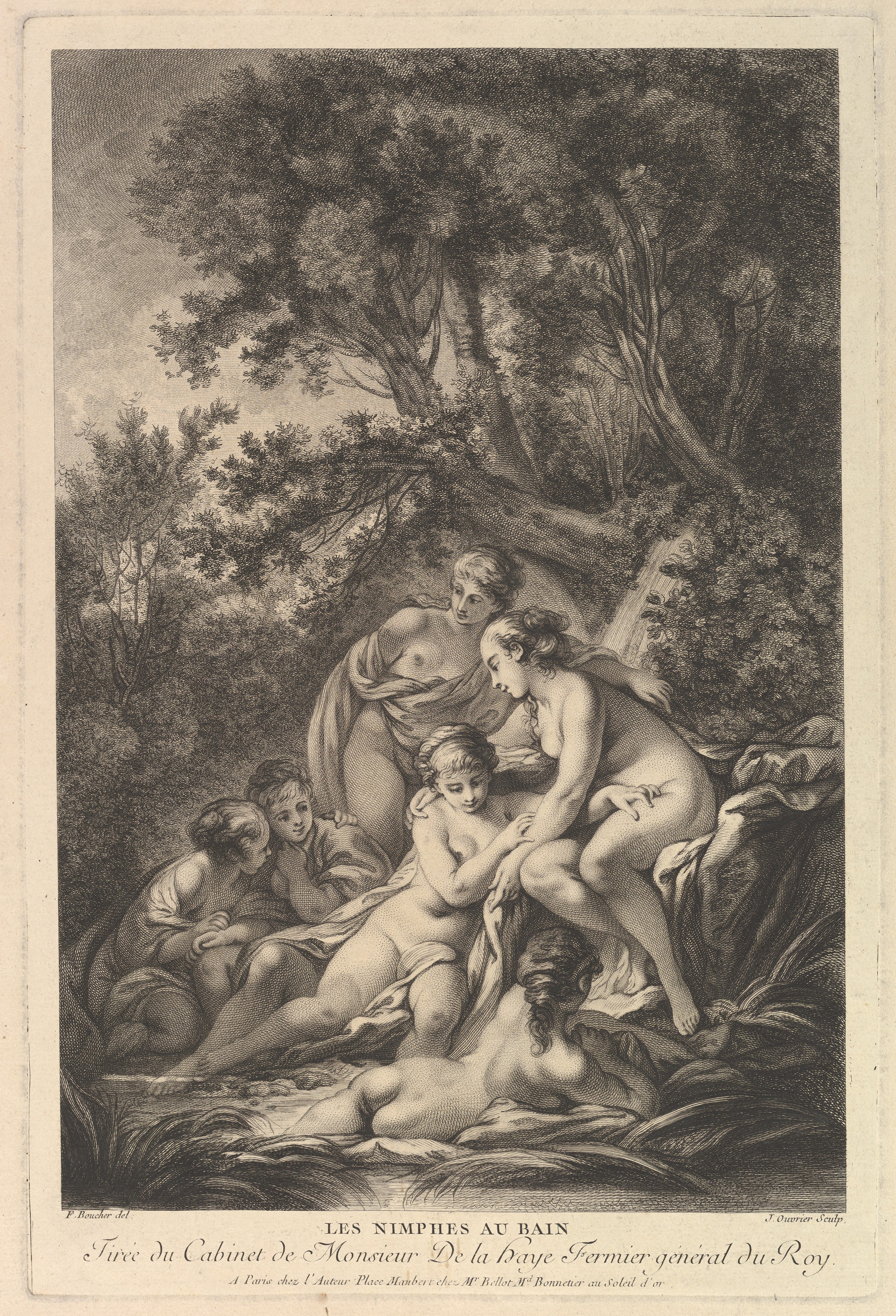

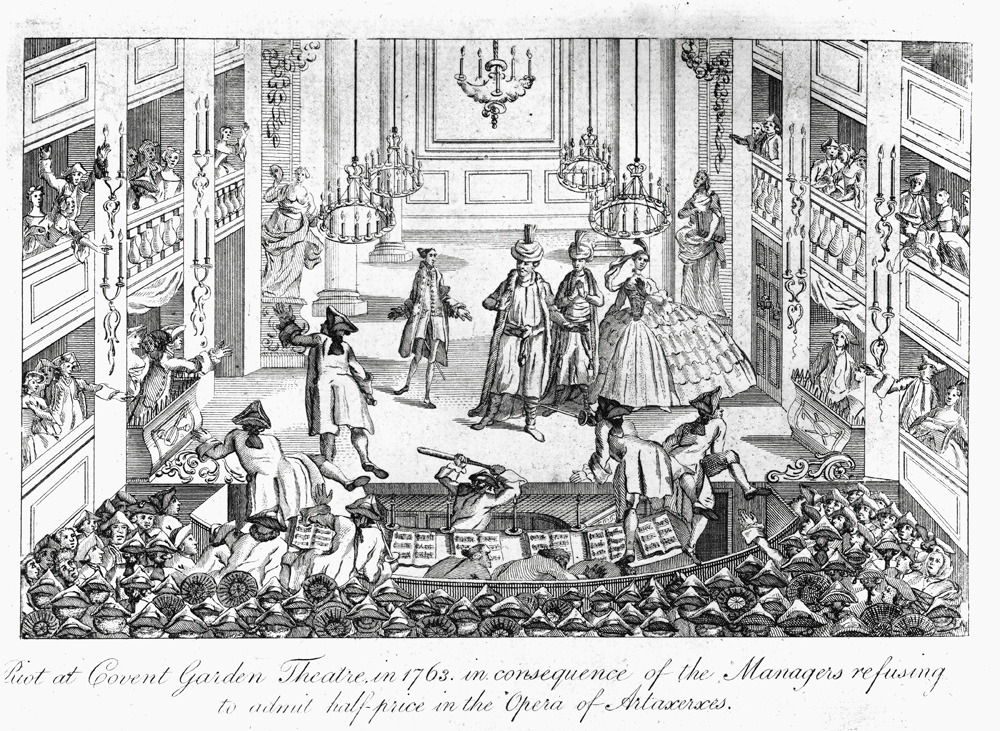

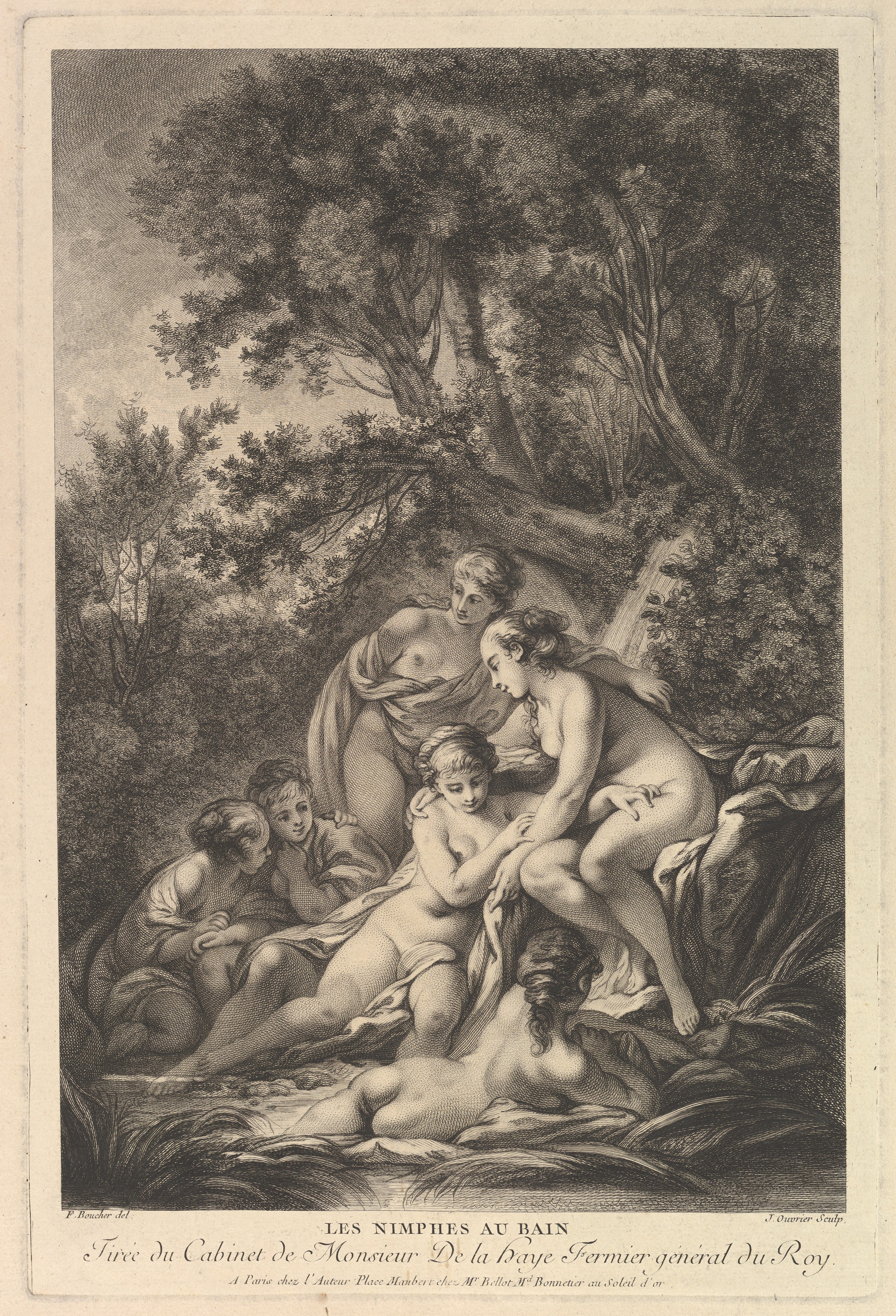

bile; figuratively, it refers to bitterness, a feature of bile. - [TH]nymph Source: Boucher, 'Les Nimphes au Bain (The Nymphs at the Bath)' (18th Century), by

Jean Ouvrier after Francois Boucher,"/>A "nymph" is a mythological

nature spirit, usually depicted as a young woman disporting, semi-nude, in

woodlands or near water. The word is often used allegorically or metaphorically to

refer to elegant, flirtatious young women. The image included here shows an

engraving, Les Nimphes au Bain (The Nymphs at the Bath), by

Jean Ouvrier after Francois Boucher, via The

Metropolitan Museum of Art. - [TH]embryoThis is an archaic spelling of

embryo. - [TH]parkSt. James's

Park was radically redeveloped by Charles II after his return to the throne as a

public space associated with the court. Here, Fantomina recounts visiting the park

to acquire the services of some young men down on their luck and willing to be

hired for a variety of services. Edmund Waller, whom Haywood quotes in her

epigraph, praised the park as a grand, idealized gathering place for the

fashionable elite in "ON St. James's PARK As lately improved by his MAJESTY"; however, John

Wilmot, second Earl of Rochester, reveals the darker, seamier side of the park in

his satire, "A Ramble

in St. James's Park". For more analysis of these competing readings of

St. James's Park in context, see Christian Verdú's ""‘Me thinks I see the love that shall be made’: Two

Restoration Views of St James Park". - [TH]mall

Source: Boucher, 'Les Nimphes au Bain (The Nymphs at the Bath)' (18th Century), by

Jean Ouvrier after Francois Boucher,"/>A "nymph" is a mythological

nature spirit, usually depicted as a young woman disporting, semi-nude, in

woodlands or near water. The word is often used allegorically or metaphorically to

refer to elegant, flirtatious young women. The image included here shows an

engraving, Les Nimphes au Bain (The Nymphs at the Bath), by

Jean Ouvrier after Francois Boucher, via The

Metropolitan Museum of Art. - [TH]embryoThis is an archaic spelling of

embryo. - [TH]parkSt. James's

Park was radically redeveloped by Charles II after his return to the throne as a

public space associated with the court. Here, Fantomina recounts visiting the park

to acquire the services of some young men down on their luck and willing to be

hired for a variety of services. Edmund Waller, whom Haywood quotes in her

epigraph, praised the park as a grand, idealized gathering place for the

fashionable elite in "ON St. James's PARK As lately improved by his MAJESTY"; however, John

Wilmot, second Earl of Rochester, reveals the darker, seamier side of the park in

his satire, "A Ramble

in St. James's Park". For more analysis of these competing readings of

St. James's Park in context, see Christian Verdú's ""‘Me thinks I see the love that shall be made’: Two

Restoration Views of St James Park". - [TH]mall Source: Nickolls, 'St. James's Park and the Mall' (1721-22)The Mall here refers not

to a shopping center but a wide path for walking or formal processions. The

accompanying image, attributed to Joseph Nickolls, shows a crowd of fashionable

people on the Mall in St. James's Park (Via Wikimedia Commons). - [TH]chameleonChameleons were long

thought to subsist on air. According to Pliny the Elder's The

Natural History, the chameleon "always holds the head upright and the

mouth open, and is the only animal which receives nourishment neither by meat nor

drink, nor anything else, but from the air alone" (8.51). These impecunious men subsist on air, except when an employer

happens upon them. It is worth noting that the chameleon, as Pliny goes on to say,

is also "very remarkable" for the "nature of its colour," which "is continually

changing; its eyes, its tail, and its whole body always assuming the colour of

whatever object is nearest, with the exception of white and red." - [TH]physiognomyPhysiognomy refers to a pseudoscience that assessed the moral character of an

individual--or a group of people--by their physical appearance. For more

information on physiognomy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, see Sarah

Waldorf's essay for The Iris, "Physiognomy, the Beautiful Pseudo-Science". For a fuller scholarly

assessment, see Kathryn Woods's "‘Facing’ Identity in a ‘Faceless’ Society: Physiognomy,

Facial Appearance and Identity Perception in Eighteenth-Century

London". - [TH]hired

Source: Nickolls, 'St. James's Park and the Mall' (1721-22)The Mall here refers not

to a shopping center but a wide path for walking or formal processions. The

accompanying image, attributed to Joseph Nickolls, shows a crowd of fashionable

people on the Mall in St. James's Park (Via Wikimedia Commons). - [TH]chameleonChameleons were long

thought to subsist on air. According to Pliny the Elder's The

Natural History, the chameleon "always holds the head upright and the

mouth open, and is the only animal which receives nourishment neither by meat nor

drink, nor anything else, but from the air alone" (8.51). These impecunious men subsist on air, except when an employer

happens upon them. It is worth noting that the chameleon, as Pliny goes on to say,

is also "very remarkable" for the "nature of its colour," which "is continually

changing; its eyes, its tail, and its whole body always assuming the colour of

whatever object is nearest, with the exception of white and red." - [TH]physiognomyPhysiognomy refers to a pseudoscience that assessed the moral character of an

individual--or a group of people--by their physical appearance. For more

information on physiognomy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, see Sarah

Waldorf's essay for The Iris, "Physiognomy, the Beautiful Pseudo-Science". For a fuller scholarly

assessment, see Kathryn Woods's "‘Facing’ Identity in a ‘Faceless’ Society: Physiognomy,

Facial Appearance and Identity Perception in Eighteenth-Century

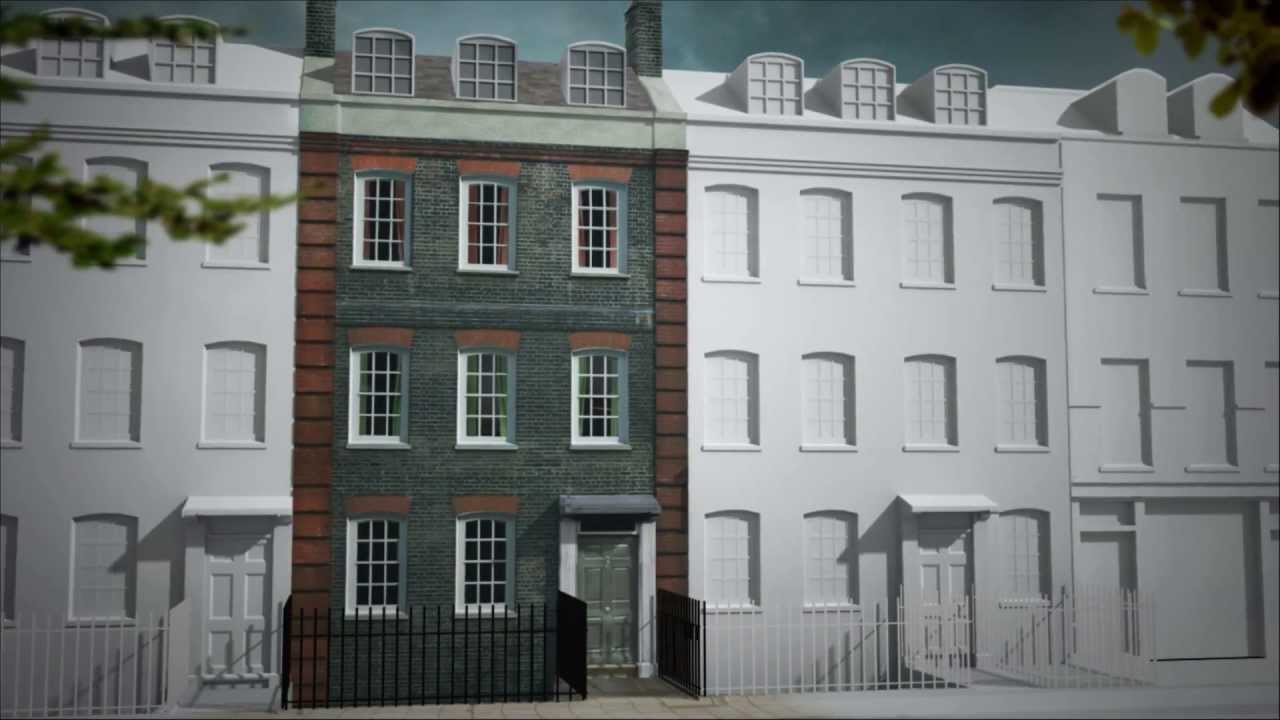

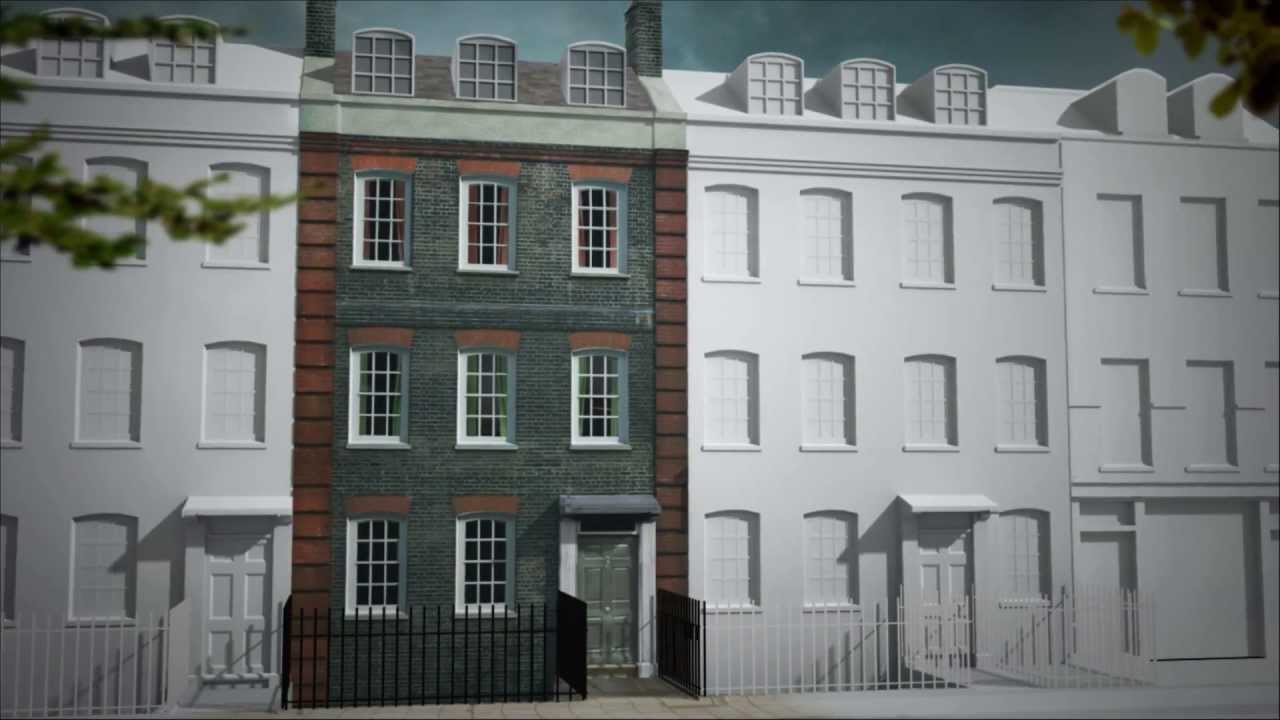

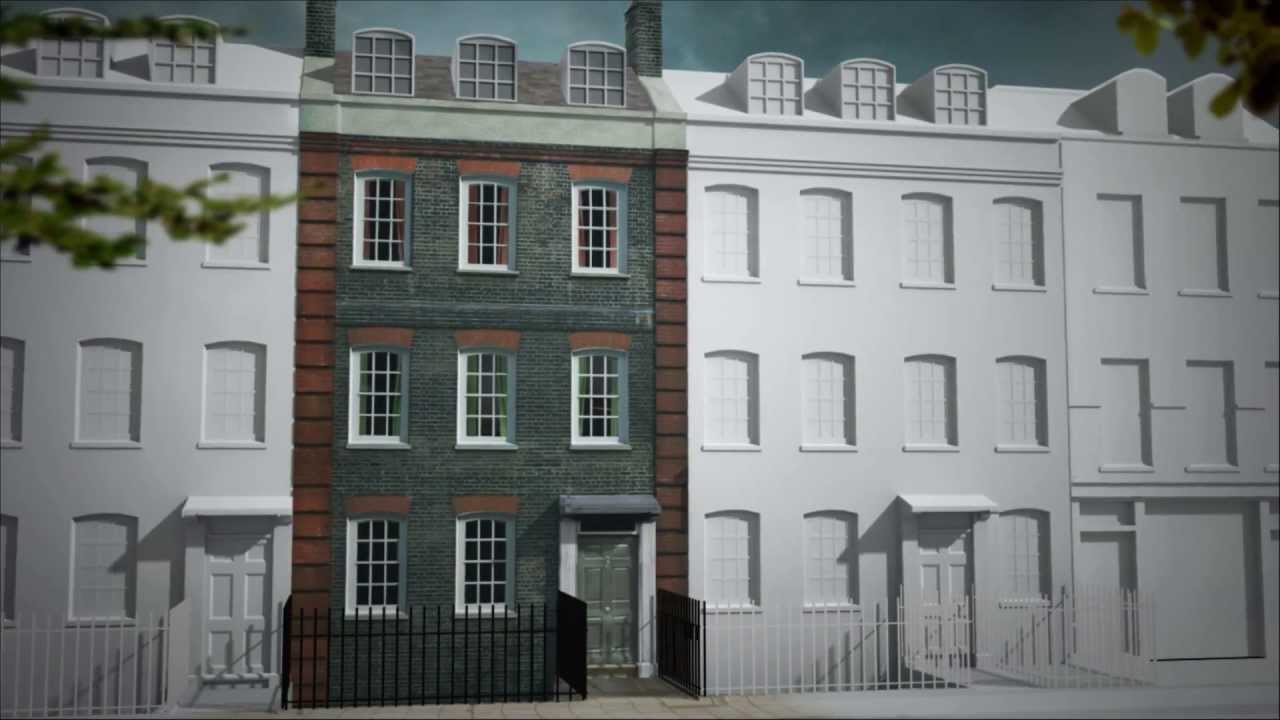

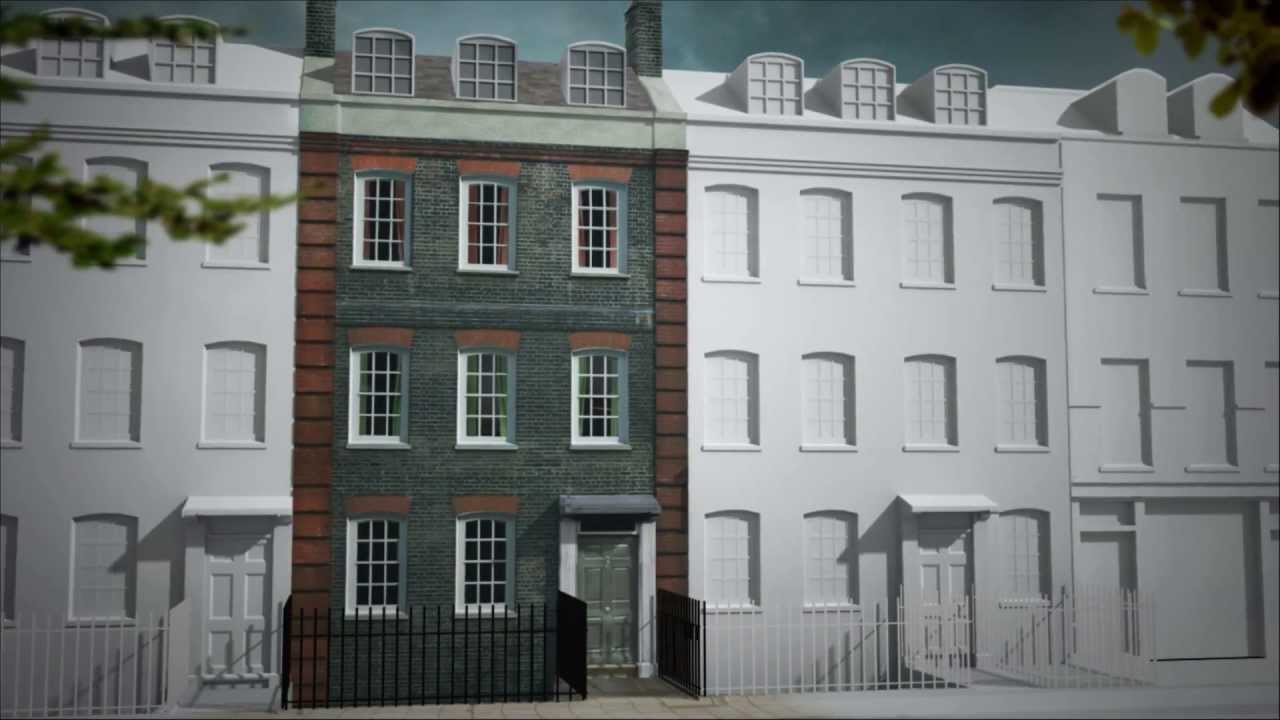

London". - [TH]hired Source: The Handel and Hendrix townhouses in LondonAs Incognita, Fantomina

would have rented what John Trusler describes as a "high rented" townhouse in a central

location. He goes on to note that "Houses about twenty-one feet in front

will let from four guineas a week furnished to eight guineas, according to the

season of the year and the time they are engaged for." This house, which is much

more magnificent, would have been about two and a half to three times the price

per week of the lodgings she took near the theaters. To learn more about London

townhomes in the eighteenth century, see Rachel Stewart's The Town House in Georgian

London (2009). The image included here, from the Handel Hendrix town

home on Brook Street, London, depicts an excellent example of a large town home

built during the early eighteenth century. - [TH]livery

Source: The Handel and Hendrix townhouses in LondonAs Incognita, Fantomina

would have rented what John Trusler describes as a "high rented" townhouse in a central

location. He goes on to note that "Houses about twenty-one feet in front

will let from four guineas a week furnished to eight guineas, according to the

season of the year and the time they are engaged for." This house, which is much

more magnificent, would have been about two and a half to three times the price

per week of the lodgings she took near the theaters. To learn more about London

townhomes in the eighteenth century, see Rachel Stewart's The Town House in Georgian

London (2009). The image included here, from the Handel Hendrix town

home on Brook Street, London, depicts an excellent example of a large town home

built during the early eighteenth century. - [TH]livery Source: Formal livery, via Colonial WilliamsburgLivery is the term given to the uniform worn by a household servant. In this

image, showing a formal ball entrance reconstructed at Colonial Williamsburg, the

two flanking servants are wearing the livery of the house (via Colonial Williamsburg

Foundation). - [TH]incognitaIncognita is a feminine form of

the Italian "incognito," meaning one who is unknown or in disguise

(OED). - [TH]ball

Source: Formal livery, via Colonial WilliamsburgLivery is the term given to the uniform worn by a household servant. In this

image, showing a formal ball entrance reconstructed at Colonial Williamsburg, the

two flanking servants are wearing the livery of the house (via Colonial Williamsburg

Foundation). - [TH]incognitaIncognita is a feminine form of

the Italian "incognito," meaning one who is unknown or in disguise

(OED). - [TH]ball Source: Court dress, Museum of LondonCourt dress for both women and men was both political

and sumptuous, some of which can be seen in the accompanying image, showing an

extravagant court dress made from Spitalfields silk and housed in the Museum of London. Click this link to view a

high-resolution image of a ball at St. James's Palace, c.1766, via the Lewis

Walpole Library. To learn more about fashion at court balls in the

eighteenth century, see Hannah Greig's

"Faction and Fashion : The Politics of Court Dress in Eighteenth-Century

England." - [TH]vizard

Source: Court dress, Museum of LondonCourt dress for both women and men was both political

and sumptuous, some of which can be seen in the accompanying image, showing an

extravagant court dress made from Spitalfields silk and housed in the Museum of London. Click this link to view a

high-resolution image of a ball at St. James's Palace, c.1766, via the Lewis

Walpole Library. To learn more about fashion at court balls in the

eighteenth century, see Hannah Greig's

"Faction and Fashion : The Politics of Court Dress in Eighteenth-Century

England." - [TH]vizard Source: Drawing (c.1750) by Jean-Marc Nattier showing an aristocratic woman with vizard and fanA "vizard" is a black velvet mask worn by elite women

in the Renaissance to protect the skin from sunburn. It became a fashionable

accoutrement during the eighteenth century, when masquerades were popular, and it

was also often worn to the theater. The image included here is a French pastel

drawing (c.1750) by Jean-Marc Nattier showing an aristocratic woman with vizard

and fan (via Neil Jeffares). For more information on masquerade in the eighteenth

century, see Terry Castle's Masquerade and Civilization: The

Carnivalesque in Eighteenth-century English Culture and Fiction

(1986). - [TH]criesPenny

merchants were street vendors or hawkers; their cries would fill the streets. To

learn more about the history of street hawking in London, see "The Lost Cries of London: Reclaiming the Street Trader's Devalued Tradition,"

published in The Guardian. - [TH]lacing

Source: Drawing (c.1750) by Jean-Marc Nattier showing an aristocratic woman with vizard and fanA "vizard" is a black velvet mask worn by elite women

in the Renaissance to protect the skin from sunburn. It became a fashionable

accoutrement during the eighteenth century, when masquerades were popular, and it

was also often worn to the theater. The image included here is a French pastel

drawing (c.1750) by Jean-Marc Nattier showing an aristocratic woman with vizard

and fan (via Neil Jeffares). For more information on masquerade in the eighteenth

century, see Terry Castle's Masquerade and Civilization: The

Carnivalesque in Eighteenth-century English Culture and Fiction

(1986). - [TH]criesPenny

merchants were street vendors or hawkers; their cries would fill the streets. To

learn more about the history of street hawking in London, see "The Lost Cries of London: Reclaiming the Street Trader's Devalued Tradition,"

published in The Guardian. - [TH]lacing Source: Late 18th-century stays (VAM)Lacing here refers to the lacing up of the stays, a

shaping undergarment like the one

seen here, from the late eighteenth century, housed in the Victoria and Albert

Museum. According to Valerie Steele in The Corset: A

Cultural History, tightly laced stays were the visible sign

of strict morality" (26). - [TH]hoop

Source: Late 18th-century stays (VAM)Lacing here refers to the lacing up of the stays, a

shaping undergarment like the one

seen here, from the late eighteenth century, housed in the Victoria and Albert

Museum. According to Valerie Steele in The Corset: A

Cultural History, tightly laced stays were the visible sign

of strict morality" (26). - [TH]hoop Source: Hoop petticoat (VAM)Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth

centuries, women's formal fashion was characterized by the exaggerated bell shape

created by the hoop petticoat, an example of

which can be seen in the Victoria and Albert Museum's digital

collections. By 1750, the hoop petticoat could be as large as 1.5 meters in

diameter, and with the addition of panniers, court dress like that which Fantomina

is described as wearing--and which the included image, from the Metropolitan

Museum of Art, shows--could be notably voluminous. - [TH]midwifeUntil

the mid to late eighteenth century, childbirth was an almost exclusively female

domain. Midwives were women who had experience in both giving birth and attending

at other births. During the eighteenth century, midwifery was becoming

professionalized and as a result masculinized into obsetetric science. For more

information on the shift in the science of childbirth from a feminine tradition to

a masculine profession, see Ernelle

Fife's "Gender and Professionalism in Eighteenth-Century

Midwifery". - [TH]closet

Source: Hoop petticoat (VAM)Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth

centuries, women's formal fashion was characterized by the exaggerated bell shape

created by the hoop petticoat, an example of

which can be seen in the Victoria and Albert Museum's digital

collections. By 1750, the hoop petticoat could be as large as 1.5 meters in

diameter, and with the addition of panniers, court dress like that which Fantomina

is described as wearing--and which the included image, from the Metropolitan

Museum of Art, shows--could be notably voluminous. - [TH]midwifeUntil

the mid to late eighteenth century, childbirth was an almost exclusively female

domain. Midwives were women who had experience in both giving birth and attending

at other births. During the eighteenth century, midwifery was becoming

professionalized and as a result masculinized into obsetetric science. For more

information on the shift in the science of childbirth from a feminine tradition to

a masculine profession, see Ernelle

Fife's "Gender and Professionalism in Eighteenth-Century

Midwifery". - [TH]closet Source: Closet, Frogmore EstateIn the eighteenth century, a "closet" was a small

office or private room leading off of a bedroom; here, individuals would conduct

business, write letters, read, or converse with close acquaintances. It was not

used to store clothes. For more information, see Daily Life in

18th-Century England (85-86), or Danielle Bobker's "Literature and Culture of the Closet in the Eighteenth

Century," from which site the accompanying image, showing the Green

Closet at Frogmore, has been drawn. - [TH]monasteryThe role of the French convent in English

literary and cultural imagination is complex. Elite young women might be educated

in a convent before their marriage; the convent might also be a house of

reformation; for some women, the convent offered an intellectual alternative

alternative to marriage in the company of other women. In the English protestant

imagination, the French convent was often seen as an erotically-charged place.

As Ana Acosta writes

in "Hotbeds of Popery: Convents in the English Literary Imagination," the

convent "provided a site for amorous encounters, forced and broken vows,

sacrificed youth, and unrequited love" (619). Yet, the convent is also a

specifically female community, where women lived, worked, studied, and conversed

with other women outside of the male gaze. For futher information, see Elizabeth

Rapey's A Social History of the Cloister, reviewed by Patrick Harrigan in Historical Studies in

Education. - [TH]

Source: Closet, Frogmore EstateIn the eighteenth century, a "closet" was a small

office or private room leading off of a bedroom; here, individuals would conduct

business, write letters, read, or converse with close acquaintances. It was not

used to store clothes. For more information, see Daily Life in

18th-Century England (85-86), or Danielle Bobker's "Literature and Culture of the Closet in the Eighteenth

Century," from which site the accompanying image, showing the Green

Closet at Frogmore, has been drawn. - [TH]monasteryThe role of the French convent in English

literary and cultural imagination is complex. Elite young women might be educated

in a convent before their marriage; the convent might also be a house of

reformation; for some women, the convent offered an intellectual alternative

alternative to marriage in the company of other women. In the English protestant

imagination, the French convent was often seen as an erotically-charged place.

As Ana Acosta writes

in "Hotbeds of Popery: Convents in the English Literary Imagination," the

convent "provided a site for amorous encounters, forced and broken vows,

sacrificed youth, and unrequited love" (619). Yet, the convent is also a

specifically female community, where women lived, worked, studied, and conversed

with other women outside of the male gaze. For futher information, see Elizabeth

Rapey's A Social History of the Cloister, reviewed by Patrick Harrigan in Historical Studies in

Education. - [TH]

Source: Engraved portrait of Haywood Eliza Haywood (c.1693-1756) was a

prolific author, actor, and publisher of the early- to mid-eighteenth century. She

is most famous, today, for her novels and novellas, among which Fantominais numbered. The image included here, via

Wikimedia Commons, is an engraved frontispiece portrait by George Vertue.

Haywood wrote in a number of different genres, including amatory fiction, domestic

fiction, and essay. - [TH]wallerThis epigraph is composed of the last

couplet from "To A. H: Of the Different Successe of Their Loves," a poem by Edmund

Waller (1606-1687). Waller's poem, published in 1645, takes a

Petrarchan perspective of the relationship between the male lover and the

female beloved. This couplet was oft-quoted during the period, and features in

George Etheredge's Restoration comedy Man of Mode, where

it is spoken by the protagonist Dorimant. Read more about Waller at Encyclopaedia Britannica. - [TH]box

Source: Engraved portrait of Haywood Eliza Haywood (c.1693-1756) was a

prolific author, actor, and publisher of the early- to mid-eighteenth century. She

is most famous, today, for her novels and novellas, among which Fantominais numbered. The image included here, via

Wikimedia Commons, is an engraved frontispiece portrait by George Vertue.

Haywood wrote in a number of different genres, including amatory fiction, domestic

fiction, and essay. - [TH]wallerThis epigraph is composed of the last

couplet from "To A. H: Of the Different Successe of Their Loves," a poem by Edmund

Waller (1606-1687). Waller's poem, published in 1645, takes a

Petrarchan perspective of the relationship between the male lover and the

female beloved. This couplet was oft-quoted during the period, and features in

George Etheredge's Restoration comedy Man of Mode, where

it is spoken by the protagonist Dorimant. Read more about Waller at Encyclopaedia Britannica. - [TH]box Source: Engraving depicting a riot at Covent Garden TheatrePlayhouses

during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in England organized seating

according to price and social status. Boxes were the most expensive of seating

areas, and could hold several people in style. The image included here, from

the Victoria and Albert Museum, depicts a famous riot at Covent Garden

theater during a performance of the opera Artaxerxes in

1763. For more information about the development of theater in the eighteenth

century, see Andrew Dickson's introduction at the British Library. - [TH]toastsAccording to the OED, a

"toast" is a "[a] lady who is named as the person to whom a company is requested

to drink; often one who is the reigning belle of the season" (n2.1). - [TH]pitThe "pit" was a

mixed-sex seating area in the eighteenth-century, notable for its energy and

activity. According to The Oxford Companion to Theatre and

Performance, the "pit occupied the floor of the theatre at a lower level

than the stage and, unlike the standing pit of earlier public theatres, contained

rows of backless benches set on a raked floor. Seats in the pit were half the

price of a seat in the box and attracted a mixed audience of men and women. The

activity of the audience in the pit and the behaviour of the occupants of the

boxes, especially with the King present, were part of the theatregoing spectacle."

Prostitutes, wits, and rakes frequented the pit and the middle galleries. For more

information, see Douglas Canfield's introduction to The Broadview Anthology

of Restoration and Early Eighteenth-Century Drama

(vxiii). - [TH]hoodsThroughout

the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, hoods and

hooded cloaks were both practical and fashionable garments for women. In

the winter, hoods and masks protected the body from icy air, and they generally

allowed women more freedom to move un-seen throughout the city, as described in

this article from the BBC's History

Magazine. - [TH]galleryThe gallery-box or middle

gallery is a seating area in cost between pit and box seats. Servants often sat in

the inexpensive upper gallery seats. When Fantomina goes again tho the playhouse

on her "frolick," she sits in the gallery areas that signify her sexual

availability. Often, sex workers found partners and keepers at the playhouse,

earning the theater a reputation for sexual display. - [TH]beauplaisirBeauplaisir is a French portmanteau word meaning "beautiful pleasure." Beau was

also a generic term in the eighteenth century for a lady's suitor or sweetheart,

according to the OED. - [TH]drawing_roomThe drawing or "withdrawing" room was a room in the home of

a wealthier class of people to which women would "withdraw" after dinner, to brew

tea and converse. Later, the male contingent would join the women in the drawing

room for polite conversation and mingling. For more information on the history and

evolution of the drawing room, see this review of Jeremy Musson's Drawing

Room. - [TH]salutationsSalutations refer to

customary greetings. - [TH]genteelUsed here as an

adjective, "genteel" refers to a quality of polite refinement thought to be

possessed by those of the gentry class. According to this review of Peter

Cross's The Origins of the English Gentry, the gentry

class is "a type of lesser nobility, based on landholding," that often

dispensed justice in the locality and wielded great social power. - [TH]railleryAccording to the OED, raillery refers to "[g]ood-humoured ridicule or banter,"

which can sometimes be more satirical or mocking. - [TH]quality"Quality" is a difficult concept to grasp;

in the eighteenth century, it typically referred to rank or social position, and

more particularly, noble or high social position, as indicated by senses 4 and 5

in the OED. - [TH]chairA hackney or sedan chair was a hireable mode of

transportation that consisted of a single enclosed seat carried, on poles, by two

strong men. It was small enough to enter into the front doors of a well-appointed

house, thus ensuring secresy. Read more about the hackney or sedan chair in this article from Bath Magazine. The image

included here shows an early eighteenth-century French sedan chair, without the

horizontal carrying poles, housed

in the VAM.

Source: Engraving depicting a riot at Covent Garden TheatrePlayhouses

during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in England organized seating

according to price and social status. Boxes were the most expensive of seating

areas, and could hold several people in style. The image included here, from

the Victoria and Albert Museum, depicts a famous riot at Covent Garden

theater during a performance of the opera Artaxerxes in

1763. For more information about the development of theater in the eighteenth

century, see Andrew Dickson's introduction at the British Library. - [TH]toastsAccording to the OED, a

"toast" is a "[a] lady who is named as the person to whom a company is requested

to drink; often one who is the reigning belle of the season" (n2.1). - [TH]pitThe "pit" was a

mixed-sex seating area in the eighteenth-century, notable for its energy and

activity. According to The Oxford Companion to Theatre and

Performance, the "pit occupied the floor of the theatre at a lower level

than the stage and, unlike the standing pit of earlier public theatres, contained

rows of backless benches set on a raked floor. Seats in the pit were half the

price of a seat in the box and attracted a mixed audience of men and women. The

activity of the audience in the pit and the behaviour of the occupants of the

boxes, especially with the King present, were part of the theatregoing spectacle."

Prostitutes, wits, and rakes frequented the pit and the middle galleries. For more

information, see Douglas Canfield's introduction to The Broadview Anthology

of Restoration and Early Eighteenth-Century Drama

(vxiii). - [TH]hoodsThroughout

the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, hoods and

hooded cloaks were both practical and fashionable garments for women. In

the winter, hoods and masks protected the body from icy air, and they generally

allowed women more freedom to move un-seen throughout the city, as described in

this article from the BBC's History

Magazine. - [TH]galleryThe gallery-box or middle

gallery is a seating area in cost between pit and box seats. Servants often sat in

the inexpensive upper gallery seats. When Fantomina goes again tho the playhouse

on her "frolick," she sits in the gallery areas that signify her sexual

availability. Often, sex workers found partners and keepers at the playhouse,

earning the theater a reputation for sexual display. - [TH]beauplaisirBeauplaisir is a French portmanteau word meaning "beautiful pleasure." Beau was

also a generic term in the eighteenth century for a lady's suitor or sweetheart,

according to the OED. - [TH]drawing_roomThe drawing or "withdrawing" room was a room in the home of

a wealthier class of people to which women would "withdraw" after dinner, to brew

tea and converse. Later, the male contingent would join the women in the drawing

room for polite conversation and mingling. For more information on the history and

evolution of the drawing room, see this review of Jeremy Musson's Drawing

Room. - [TH]salutationsSalutations refer to

customary greetings. - [TH]genteelUsed here as an

adjective, "genteel" refers to a quality of polite refinement thought to be

possessed by those of the gentry class. According to this review of Peter

Cross's The Origins of the English Gentry, the gentry

class is "a type of lesser nobility, based on landholding," that often

dispensed justice in the locality and wielded great social power. - [TH]railleryAccording to the OED, raillery refers to "[g]ood-humoured ridicule or banter,"

which can sometimes be more satirical or mocking. - [TH]quality"Quality" is a difficult concept to grasp;

in the eighteenth century, it typically referred to rank or social position, and

more particularly, noble or high social position, as indicated by senses 4 and 5

in the OED. - [TH]chairA hackney or sedan chair was a hireable mode of

transportation that consisted of a single enclosed seat carried, on poles, by two

strong men. It was small enough to enter into the front doors of a well-appointed

house, thus ensuring secresy. Read more about the hackney or sedan chair in this article from Bath Magazine. The image

included here shows an early eighteenth-century French sedan chair, without the

horizontal carrying poles, housed

in the VAM. Source: Early 18th-century French sedan chair (VAM) - [TH]cogitations"Cogitations" are thoughts; often, the word contains a humourously exaggerated

connotation. - [TH]devoirsFrom the French word for duty, "devoirs" are

dutiful addresses paid to someone out of respect or courtesy. See sense 4 in the

OED. - [TH]lodgingsFantomina explains that she rented rooms near the playhouse, which were centrally

located and more expensive than houses or rooms in houses further afield. She

would likely have rented the furnished first floor for between 2 and 4 guineas per

week, according to John Trusler's late eighteenth-century London Adviser and

Guide. For a sense of the cost of living in the period, see "Currency, Coinage

and the Cost of Living" at the Old Bailey Online. For a good overview of

early Georgian town houses, see this Google

Arts and Culture Spotter's Guide. - [TH]collationA "collation," according to the OED, is a light, often cold

meal of meats, fruits, and wine that has little to no need of preparation. - [TH]houseWhen renting furnished rooms, a lodger might bring their own

servant or use the servants who work consistently at the house. Here, we learn

that Fantomina did not bring her own servant, but drew on the services of those

from whom she rented. - [TH]honourHonor, in this sense, is being used to refer to Fantomina's

"virtue as regards sexual morality," according to sense 7 in the OED--or, "a

reputation for this, one's good name." - [TH]countryA country gentleman would

be a member of the landed gentry, residing most likely in a country house or

mansion where the business of the locality was often conducted. The country

gentleman would likely have also had a town house in London. To read more about

the country house, see Mark Girouard's Life in the English Country House: A Social and Architectural

History (1978). - [TH]pieceA broad

piece is a coin approximately the same as a pound, worth 20 shillings. It was

called a "broad piece" because it was thicker and and bigger than newer coins,

minted after 1663. See "A Note on British

Money", included in the Broadview edition of Anti-Pamela and

Shamela (50ff). - [TH]barge

Source: Early 18th-century French sedan chair (VAM) - [TH]cogitations"Cogitations" are thoughts; often, the word contains a humourously exaggerated

connotation. - [TH]devoirsFrom the French word for duty, "devoirs" are

dutiful addresses paid to someone out of respect or courtesy. See sense 4 in the

OED. - [TH]lodgingsFantomina explains that she rented rooms near the playhouse, which were centrally

located and more expensive than houses or rooms in houses further afield. She

would likely have rented the furnished first floor for between 2 and 4 guineas per

week, according to John Trusler's late eighteenth-century London Adviser and

Guide. For a sense of the cost of living in the period, see "Currency, Coinage

and the Cost of Living" at the Old Bailey Online. For a good overview of

early Georgian town houses, see this Google

Arts and Culture Spotter's Guide. - [TH]collationA "collation," according to the OED, is a light, often cold

meal of meats, fruits, and wine that has little to no need of preparation. - [TH]houseWhen renting furnished rooms, a lodger might bring their own

servant or use the servants who work consistently at the house. Here, we learn

that Fantomina did not bring her own servant, but drew on the services of those

from whom she rented. - [TH]honourHonor, in this sense, is being used to refer to Fantomina's

"virtue as regards sexual morality," according to sense 7 in the OED--or, "a

reputation for this, one's good name." - [TH]countryA country gentleman would

be a member of the landed gentry, residing most likely in a country house or

mansion where the business of the locality was often conducted. The country

gentleman would likely have also had a town house in London. To read more about

the country house, see Mark Girouard's Life in the English Country House: A Social and Architectural

History (1978). - [TH]pieceA broad

piece is a coin approximately the same as a pound, worth 20 shillings. It was

called a "broad piece" because it was thicker and and bigger than newer coins,

minted after 1663. See "A Note on British

Money", included in the Broadview edition of Anti-Pamela and

Shamela (50ff). - [TH]barge Source: https://www.rct.uk/collection/404760/a-view-of-hampton-courtThe river Thames was a

source of work, pleasure, and transportation in the eighteenth century; it

connected many significant country towns to London, and access to Hampton Court

Palace as well as the many London pleasure gardens was primarily accomplished via

the river. To

learn more about the history of the Thames, see this BBC article by Andy

Dangerfield. The image included here, an early

eighteenth-century painting by Leonard Knyff via the Royal Collection

Trust, shows Hampton Court Palace and the barges passing on the river

Thames. - [TH]intrigueAccording to the OED, an "intrigue" is at once a secret

intimacy between lovers, as well as an intricate or maze-like contrivance,

perhaps enabling the clandestine romance. - [TH]habitA habit used in this sense refers to a particular garment or

mode of dress, often specific to a profession or activity. See the OED senses 1

and 2. - [TH]chapelFantomina

here likely refers to the Chapel Royal at St. James's Palace. During the Georgian

period, the Chapel Royal became "a significant cultural centre." For more

information on the Chapel Royal, see this article by Carolyn Harris. - [TH]gardens

Source: https://www.rct.uk/collection/404760/a-view-of-hampton-courtThe river Thames was a

source of work, pleasure, and transportation in the eighteenth century; it

connected many significant country towns to London, and access to Hampton Court

Palace as well as the many London pleasure gardens was primarily accomplished via

the river. To

learn more about the history of the Thames, see this BBC article by Andy

Dangerfield. The image included here, an early

eighteenth-century painting by Leonard Knyff via the Royal Collection

Trust, shows Hampton Court Palace and the barges passing on the river

Thames. - [TH]intrigueAccording to the OED, an "intrigue" is at once a secret

intimacy between lovers, as well as an intricate or maze-like contrivance,

perhaps enabling the clandestine romance. - [TH]habitA habit used in this sense refers to a particular garment or

mode of dress, often specific to a profession or activity. See the OED senses 1

and 2. - [TH]chapelFantomina

here likely refers to the Chapel Royal at St. James's Palace. During the Georgian

period, the Chapel Royal became "a significant cultural centre." For more

information on the Chapel Royal, see this article by Carolyn Harris. - [TH]gardens Source: Jan Kip, plan of St.James's Palace and Gardens, early 18th centuryThe

palace gardens at St. James's Palace, which was the primary royal residence until

early nineteenth century, are pictured in the bird's eye plan by Jan Kip shown

here (via Wikimedia Commons). Something of the spirit of the parks and gardens of

the period can be grasped by examining the 1745 painting of St. James's Park and the Mall, by Joseph Nickolls,

discussed here. - [TH]opera

Source: Jan Kip, plan of St.James's Palace and Gardens, early 18th centuryThe

palace gardens at St. James's Palace, which was the primary royal residence until

early nineteenth century, are pictured in the bird's eye plan by Jan Kip shown

here (via Wikimedia Commons). Something of the spirit of the parks and gardens of

the period can be grasped by examining the 1745 painting of St. James's Park and the Mall, by Joseph Nickolls,

discussed here. - [TH]opera Source: Engraving depicting a riot at Covent Garden TheatreOpera became

extraordinarily fashionable during the eighteenth century. Read more about the

history of opera during the period from the

Victoria and Albert Museum. The image included here shows a riot during

an opera at Covent Garden Theatre in 1763. - [TH]poignancyAccording to the OED,

"poingnancy" refers to the sharpness or piquancy of a feeling. - [TH]dissembleTo

"dissemble" is to disguise or feign--to appear otherwise (OED). - [TH]bathBath is a fashionable resort and thermal spa town located in

the south west of England, near Bristol. In the eighteenth century, it became a

destination and, according to the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, "one of the most beautiful cities

in Europe, with architecture and landscape combined harmoniously for the

enjoyment of the spa town’s cure takers." - [TH]wagonA wagon is a much ruder

form of transportation than the elegant coach, befitting Fantomina's new

character. Travel by stage coach from London to Bath during this period would have

taken at least two days. - [TH]cap

Source: Engraving depicting a riot at Covent Garden TheatreOpera became

extraordinarily fashionable during the eighteenth century. Read more about the

history of opera during the period from the

Victoria and Albert Museum. The image included here shows a riot during

an opera at Covent Garden Theatre in 1763. - [TH]poignancyAccording to the OED,

"poingnancy" refers to the sharpness or piquancy of a feeling. - [TH]dissembleTo

"dissemble" is to disguise or feign--to appear otherwise (OED). - [TH]bathBath is a fashionable resort and thermal spa town located in

the south west of England, near Bristol. In the eighteenth century, it became a

destination and, according to the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, "one of the most beautiful cities

in Europe, with architecture and landscape combined harmoniously for the

enjoyment of the spa town’s cure takers." - [TH]wagonA wagon is a much ruder

form of transportation than the elegant coach, befitting Fantomina's new

character. Travel by stage coach from London to Bath during this period would have

taken at least two days. - [TH]cap Source: Round-eared cap (VAM)According to The

Dictionary of Fashion History, a round-eared cap is a "white

indoor cap curving round the face to the level of the ears or below," often

ruffled, and drawn close with a string along the shallow back edge of the cap.

These caps were popular among all classes from around 1730 to 1760, making this an

early reference. The image included here, from the Victoria and Albert Museum, shows a mannequin in a quilted green

petticoat and round-eared cap. - [TH]stuff"Stuff" here

refers to a type of woven material made of worsted woollen cloth. See OED sense

5c. - [TH]maidA maidservant was one of the lowest-paid

members of a domestic household, though others--like scullery maids, who were

responsible for scrubbing kitchen pans--earned much less. A housemaid was

typically responsible for airing rooms, emptying chamber pots, cleaning and

beating rugs and beds, and so on. For more information on female domestic

servants, see Part 12

of Eighteenth-Century Women: An Anthology, Volume

21. - [TH]waters

Source: Round-eared cap (VAM)According to The

Dictionary of Fashion History, a round-eared cap is a "white

indoor cap curving round the face to the level of the ears or below," often

ruffled, and drawn close with a string along the shallow back edge of the cap.

These caps were popular among all classes from around 1730 to 1760, making this an

early reference. The image included here, from the Victoria and Albert Museum, shows a mannequin in a quilted green

petticoat and round-eared cap. - [TH]stuff"Stuff" here

refers to a type of woven material made of worsted woollen cloth. See OED sense

5c. - [TH]maidA maidservant was one of the lowest-paid

members of a domestic household, though others--like scullery maids, who were

responsible for scrubbing kitchen pans--earned much less. A housemaid was

typically responsible for airing rooms, emptying chamber pots, cleaning and

beating rugs and beds, and so on. For more information on female domestic

servants, see Part 12

of Eighteenth-Century Women: An Anthology, Volume

21. - [TH]waters Source: Rowlandson, 'The Comforts of Bath' (1798)Througout the

eighteenth century, Bath--known for its thermal springs--became a fashionable

place to relax and "take the waters." Thomas Rowlandson's satirical 1798 watercolor, "The Comforts of Bath: The Pump

Room," included here via Wikimedia Commons, depicts patients suffering

from a variety of illnesses descending on the Pump Room to drink the hot mineral

spring waters. It was believed that the mineral spring waters had curative

properties, though many people went to Bath for relaxation and leisure in

general. - [TH]celiaCelia is a generic pastoral female name. - [TH]service"Service" in this sense

refers to the position of domestic servitude she has acquired (OED). - [TH]mourning_

Source: Rowlandson, 'The Comforts of Bath' (1798)Througout the

eighteenth century, Bath--known for its thermal springs--became a fashionable

place to relax and "take the waters." Thomas Rowlandson's satirical 1798 watercolor, "The Comforts of Bath: The Pump

Room," included here via Wikimedia Commons, depicts patients suffering

from a variety of illnesses descending on the Pump Room to drink the hot mineral

spring waters. It was believed that the mineral spring waters had curative

properties, though many people went to Bath for relaxation and leisure in

general. - [TH]celiaCelia is a generic pastoral female name. - [TH]service"Service" in this sense

refers to the position of domestic servitude she has acquired (OED). - [TH]mourning_ Source: Portrait of a widow in mourning garbIn this enamel miniature portrait c.1710, via Philip

Mould and Company, the artist

Christian Zincke has depicted Henrietta Maria, Lady Ashburnham, in first

mourning for her husband; Henrietta Maria is twenty-three in this

portrait. First or deep mourning lasted approximately three months after

the death of a spouse, during which time the mourner wore non-reflective black

fabrics like bombazine. - [TH]pinnersA pinner is, according to

the OED, a cap with long flaps on either side that fits more tightly around the

head; it is often worn by women of higher social standing. "Pinners" also refers

to the flaps on either side of the cap. - [TH]bristolBristol is a port town about 15 miles

west of Bath. - [TH]ephesian_matronIn the story of the Ephesian matron, first

told in Petronius' Satyricon, a new widow in deep mourning

for her husband and known for her chastity is seduced by a soldier tasked with

guarding the crucified bodies of three theives. While the soldier and the

beautiful young widow are otherwise employed, one of the bodies disappears, and to

save her lover, the widow replaces the missing thief with her husband's corpse.

This story was adapted in the seventeenth century by Jean de La Fontaine. Read

more about this story and the seventeenth-century adaptation that Haywood would

have known of in Robert

Colton's article, "The Story of the Widow of Ephesus in Petronius and La

Fontaine."

- [TH]narratorWhile

"Fantomina" appears to be told in the third person omniscient, there is a

first-person narrator who interjects at points with her own thoughts, as she does

here. - [TH]billetA "billet" is the French

word for letter; a billet doux is a love letter. - [TH]hand"Hand" here refers to the

style of handwriting used in the letter. - [TH]gallGall is another word for

bile; figuratively, it refers to bitterness, a feature of bile. - [TH]nymph

Source: Portrait of a widow in mourning garbIn this enamel miniature portrait c.1710, via Philip

Mould and Company, the artist

Christian Zincke has depicted Henrietta Maria, Lady Ashburnham, in first

mourning for her husband; Henrietta Maria is twenty-three in this

portrait. First or deep mourning lasted approximately three months after

the death of a spouse, during which time the mourner wore non-reflective black

fabrics like bombazine. - [TH]pinnersA pinner is, according to

the OED, a cap with long flaps on either side that fits more tightly around the

head; it is often worn by women of higher social standing. "Pinners" also refers

to the flaps on either side of the cap. - [TH]bristolBristol is a port town about 15 miles

west of Bath. - [TH]ephesian_matronIn the story of the Ephesian matron, first

told in Petronius' Satyricon, a new widow in deep mourning

for her husband and known for her chastity is seduced by a soldier tasked with

guarding the crucified bodies of three theives. While the soldier and the

beautiful young widow are otherwise employed, one of the bodies disappears, and to

save her lover, the widow replaces the missing thief with her husband's corpse.

This story was adapted in the seventeenth century by Jean de La Fontaine. Read

more about this story and the seventeenth-century adaptation that Haywood would

have known of in Robert

Colton's article, "The Story of the Widow of Ephesus in Petronius and La

Fontaine."

- [TH]narratorWhile

"Fantomina" appears to be told in the third person omniscient, there is a

first-person narrator who interjects at points with her own thoughts, as she does

here. - [TH]billetA "billet" is the French

word for letter; a billet doux is a love letter. - [TH]hand"Hand" here refers to the

style of handwriting used in the letter. - [TH]gallGall is another word for

bile; figuratively, it refers to bitterness, a feature of bile. - [TH]nymph Source: Boucher, 'Les Nimphes au Bain (The Nymphs at the Bath)' (18th Century), by

Jean Ouvrier after Francois Boucher,"/>A "nymph" is a mythological

nature spirit, usually depicted as a young woman disporting, semi-nude, in

woodlands or near water. The word is often used allegorically or metaphorically to

refer to elegant, flirtatious young women. The image included here shows an

engraving, Les Nimphes au Bain (The Nymphs at the Bath), by

Jean Ouvrier after Francois Boucher, via The

Metropolitan Museum of Art. - [TH]embryoThis is an archaic spelling of

embryo. - [TH]parkSt. James's

Park was radically redeveloped by Charles II after his return to the throne as a

public space associated with the court. Here, Fantomina recounts visiting the park

to acquire the services of some young men down on their luck and willing to be

hired for a variety of services. Edmund Waller, whom Haywood quotes in her

epigraph, praised the park as a grand, idealized gathering place for the

fashionable elite in "ON St. James's PARK As lately improved by his MAJESTY"; however, John

Wilmot, second Earl of Rochester, reveals the darker, seamier side of the park in

his satire, "A Ramble