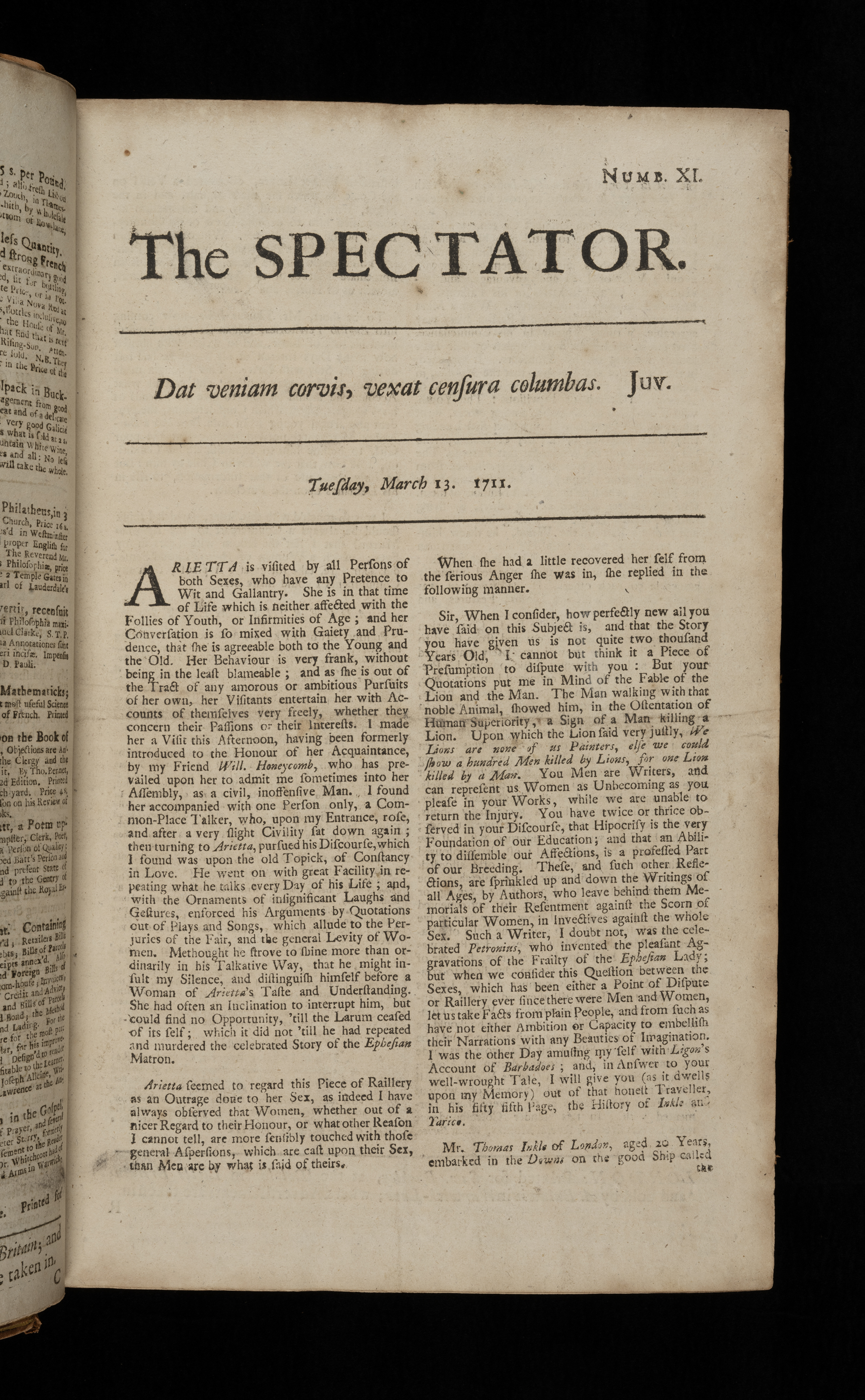

The Spectator, Issue 11, Tuesday, March 13, 1711.

By

Richard Steele

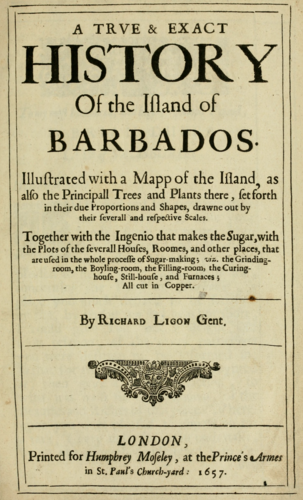

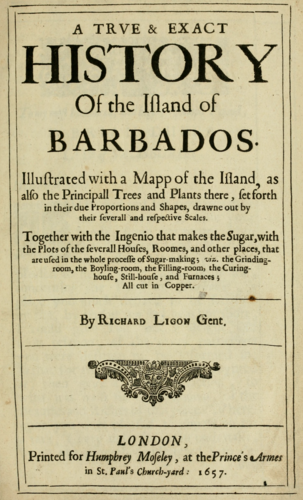

Source: Title page of Richard Ligon's A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (Hathi Trust) For the most part, Ligon's book is what the title states, a careful description of the island of Barbados for the use of anyone in England who was interested in traveling or investing there. But he does include this (apparently) fictional story of a young man who fell in love with, but then betrayed, a native woman. Here is the original version, from Ligon:

Source: Title page of Richard Ligon's A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (Hathi Trust) For the most part, Ligon's book is what the title states, a careful description of the island of Barbados for the use of anyone in England who was interested in traveling or investing there. But he does include this (apparently) fictional story of a young man who fell in love with, but then betrayed, a native woman. Here is the original version, from Ligon: This Indian dwelling neer the Sea-coast, upon the Main, an English ship put in to a Bay, and sent some of her men a shoar, to try what victualls or water they could finde, for in some distresse they were: But the Indians perceiving them to go up so far into the Country, as they were sure they could not make a safe retreat, intercepted them in their return, and fell upon them, chasing them into a Wood, and being dispersed there, some were taken, and some kill’d: but a young man amongst them stragling from the rest, was met by this Indian Maid, who upon the first sight fell in love with him, and hid him close from her Countrymen (the Indians) in a Cave, and there fed him, till they could safely go down to the shoar, where the ship lay at anchor, expecting the return of their friends.

But at last, seeing them upon the shoar, sent the long-Boat for them, took them aboard, and brought them away. But the youth, when he came ashoar in the Barbadoes, forgot the kindnesse of the poor maid, that had ventured her life for his safety, and sold her for a slave, who was as free born as he: And so poor Yarico for her love, lost her liberty. - [JOB]prepossessionBias or predisposition. Source: Oxford English DictionaryhillockA small hill. Source: Oxford English DictionaryrepastMeal. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryslaketo ease or satisfybuglesTube-shaped beads used for jewellery. Source: Oxford English DictionarybredesBraids or plaits. Source: Oxford English DictionarycommiseratePity or sympathize. Source: Oxford English Dictionary

Tuesday, March 13, 1711.

Dat veniam corvis, vexat censura columbas.--Juv.JuvenalJuvenal"Our censors indulge crows, but harass doves." Juvenal. The line is taken from the first Satire of the Roman poet Juvenal, written in the first century. What is Steele trying to say by including this epigraph? One way of reading it is that Steele is thinking of a gendered allegory, with men in the role of crows and women as doves; thus he is implying that the kind of behavior that women get condemned for is something that men get away with. Like the essay that follows, the epigraph is ambiguous, requiring the reader to put the pieces together and interpret it for him or herself. - [JOB]

Arietta is visited by all Persons of both Sexes, who may have any Pretence to Wit and GallantrygallantrygallantryPoliteness, especially on the part of a man.. She is in that time of Life which is neither affected with the Follies of Youth or infirmitiesinfirmitiesinfirmitiesWeaknesses. Source: Oxford English Dictionary of Age; and her Conversation is so mixed with GaietygaietygaietyCheerfulness. Source: Oxford English Dictionary and Prudence, that she is agreeable both to the Young and the Old. Her Behaviour is very frank, without being in the least blameable; and as she is out of the Tract of any amorous or ambitious Pursuits of her own, her Visitants entertain her with Accounts of themselves very freely, whether they concern their Passions or their Interests. I made her a Visit this Afternoon, having been formerly introduced to the Honour of her Acquaintance, by my friend Will. Honeycomb, who has prevailed upon her to admit me sometimes into her Assembly, as a civil, inoffensive Man. I found her accompanied with one Person only, a Common-Place TalkertalkertalkerA bore; someone who utters only common-places or clichés. Source: Oxford English Dictionary, who, upon my Entrance, rose, and after a very slight Civility sat down again then turning to Arietta, pursued his Discourse, which I found was upon the old Topick, of Constancy in Love. He went on with great Facility in repeating what he talks every Day of his Life; and, with the Ornaments of insignificant Laughs and Gestures, enforced his Arguments by Quotations out of Plays and Songs, which allude to the Perjuries of the Fair, the general LevitylevitylevityLightness; lack of seriousness. Source: Oxford English Dictionary of Women. Methought he strove to shine more than ordinarily in his Talkative Way, that he might insult my Silence, and distinguish himself before a Woman of Arietta's Taste and Understanding. She had often an Inclination to interrupt him, but could find no Opportunity, 'till the LarumlarumlarumAlarm; that is, this talkative man (who is clearly the opposite of the silent Mr. Spectator), rattles on like an alarm bell. Source: Oxford English Dictionary ceased of its self; which it did not 'till he had repeated and murdered the celebrated Story of the Ephesian MatronEphesianEphesianThis story, which comes from the Satyricon by the Roman writer Petronius, would have been so well known to his original readers that Steele did not have tell it. But it is not well known any more, so here is a brief summary. The husband of a woman from Ephesus died, and she was so wracked with grief that she accompanied him to his tomb. She stayed with the body for days, mourning and refusing to eat. The people of Ephesus were concerned for her, but also thought of her as a model of the faithful wife. Meanwhile, the governor of the province ordered the bodies of some robbers to be nailed to crosses near the tomb. A soldier sent to guard the bodies saw the light in the tomb, and, visiting the woman, tried to console her and encouraged her to eat. Eventually, she gave in, and then the soldier seduced her, and they had sex; in fact, they stayed in the tomb together for several days, with everyone around assuming that she had died of grief and hunger. But because the bodies of the robbers had been left unguarded, one of them was taken down by his family, who gave it an appropriate burial. Finally seeing the empty cross, and fearing that the soldier would be blamed and perhaps executed for dereliction of duty, the woman had the corpse of her husband put on the empty cross, since she would rather save a living man than preserve a dead one. - [JOB].

Arietta seemed to regard this Piece of RailleryrailleryrailleryMockery, banter. Source: Oxford English Dictionary as an Outrage done to her Sex; as indeed I have always observed that Women, whether out of a nicer Regard to their Honour, or what other Reason I cannot tell, are more sensibly touched with those general AspersionsaspersionsaspersionsDamaging reports or insinuations, often of a slanderous nature. Source: Oxford English Dictionary, which are cast upon their Sex, than Men are by what is said of theirs.

When she had a little recovered her self from the serious Anger she was in, she replied in the following manner.

Sir, when I consider, how perfectly new all you have said on this Subject is, and that the Story you have given us is not quite two thousand Years Old, I cannot but think it a Piece of PresumptionpresumptionpresumptionArrogance. Source: Oxford English Dictionary to dispute with you: But your Quotations put me in Mind of the Fable of the Lion and the Manlionlion"The Man and the Lion" is one of Aesop's Fables, that highlights the need to examine one's evidence before it is presented or accepted. The fable shows a man and a lion disputing over which of them is better. To make his point the man points to a statue of a man that has subdued a lion. Undermining the man, the lion points out that if lions could sculpt they would most certainly create the statue the other way around. Later versions alter the story replacing the sculpture with instead a painting of a man subduing a lion. Source: Wikipedia. The Man walking with that noble Animal, showed him, in the Ostentation of Human Superiority, a Sign of a Man killing a Lion. Upon which the Lion said very justly, We Lions are none of us Painters, else we could show a hundred Men ruled by Lions, for one Lion killed by a Man. You Men are Writers, and can represent us Women as Unbecoming as you please in your Works, while we are unable to return the Injury. You have twice or thrice observed in your Discourse, that Hypocrisy is the very Foundation of our Education; and that an Ability to dissemble our affections, is a professed Part of our Breeding. These, and such other Reflections, are sprinkled up and down the Writings of all Ages, by Authors, who leave behind them Memorials of their Resentment against the Scorn of particular Women, in InvectivesinvectivesinvectivesViolent attacks with words. Source: Oxford English Dictionary against the whole Sex. Such a Writer, I doubt not, was the celebrated PetroniusPetroniusPetroniusThe supposed author of the Satyricon, the work that the story of the Ephesian matron comes from. Source: Oxford English Dictionary, who invented the pleasant Aggravations of the Frailty of the Ephesian Lady; but when we consider this Question between the Sexes, which has been either a Point of Dispute or Raillery ever since there were Men and Women, let us take Facts from plain People, and from such as have not either Ambition or Capacity to embellish their Narrations with any Beauties of Imagination. I was the other Day amusing myself with Ligon's Account of Barbadoes; and, in Answer to your well-wrought Tale, I will give you (as it dwells upon my Memory) Out of that honest Traveller, in his fifty fifth page, the History of Inkle and YaricoLigonLigonA True and Exact History of Barbadoes, written by Richard Ligon and published in 1657, is the source for the following story.  Source: Title page of Richard Ligon's A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (Hathi Trust) For the most part, Ligon's book is what the title states, a careful description of the island of Barbados for the use of anyone in England who was interested in traveling or investing there. But he does include this (apparently) fictional story of a young man who fell in love with, but then betrayed, a native woman. Here is the original version, from Ligon:

Source: Title page of Richard Ligon's A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (Hathi Trust) For the most part, Ligon's book is what the title states, a careful description of the island of Barbados for the use of anyone in England who was interested in traveling or investing there. But he does include this (apparently) fictional story of a young man who fell in love with, but then betrayed, a native woman. Here is the original version, from Ligon:

This Indian dwelling neer the Sea-coast, upon the Main, an English ship put in to a Bay, and sent some of her men a shoar, to try what victualls or water they could finde, for in some distresse they were: But the Indians perceiving them to go up so far into the Country, as they were sure they could not make a safe retreat, intercepted them in their return, and fell upon them, chasing them into a Wood, and being dispersed there, some were taken, and some kill’d: but a young man amongst them stragling from the rest, was met by this Indian Maid, who upon the first sight fell in love with him, and hid him close from her Countrymen (the Indians) in a Cave, and there fed him, till they could safely go down to the shoar, where the ship lay at anchor, expecting the return of their friends.

But at last, seeing them upon the shoar, sent the long-Boat for them, took them aboard, and brought them away. But the youth, when he came ashoar in the Barbadoes, forgot the kindnesse of the poor maid, that had ventured her life for his safety, and sold her for a slave, who was as free born as he: And so poor Yarico for her love, lost her liberty. - [JOB].

Mr. Thomas Inkle of London, aged twenty Years, embarked in the Downs, on the good Ship called

Footnotes

Source: Title page of Richard Ligon's A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (Hathi Trust) For the most part, Ligon's book is what the title states, a careful description of the island of Barbados for the use of anyone in England who was interested in traveling or investing there. But he does include this (apparently) fictional story of a young man who fell in love with, but then betrayed, a native woman. Here is the original version, from Ligon:

Source: Title page of Richard Ligon's A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (Hathi Trust) For the most part, Ligon's book is what the title states, a careful description of the island of Barbados for the use of anyone in England who was interested in traveling or investing there. But he does include this (apparently) fictional story of a young man who fell in love with, but then betrayed, a native woman. Here is the original version, from Ligon: This Indian dwelling neer the Sea-coast, upon the Main, an English ship put in to a Bay, and sent some of her men a shoar, to try what victualls or water they could finde, for in some distresse they were: But the Indians perceiving them to go up so far into the Country, as they were sure they could not make a safe retreat, intercepted them in their return, and fell upon them, chasing them into a Wood, and being dispersed there, some were taken, and some kill’d: but a young man amongst them stragling from the rest, was met by this Indian Maid, who upon the first sight fell in love with him, and hid him close from her Countrymen (the Indians) in a Cave, and there fed him, till they could safely go down to the shoar, where the ship lay at anchor, expecting the return of their friends.

But at last, seeing them upon the shoar, sent the long-Boat for them, took them aboard, and brought them away. But the youth, when he came ashoar in the Barbadoes, forgot the kindnesse of the poor maid, that had ventured her life for his safety, and sold her for a slave, who was as free born as he: And so poor Yarico for her love, lost her liberty.