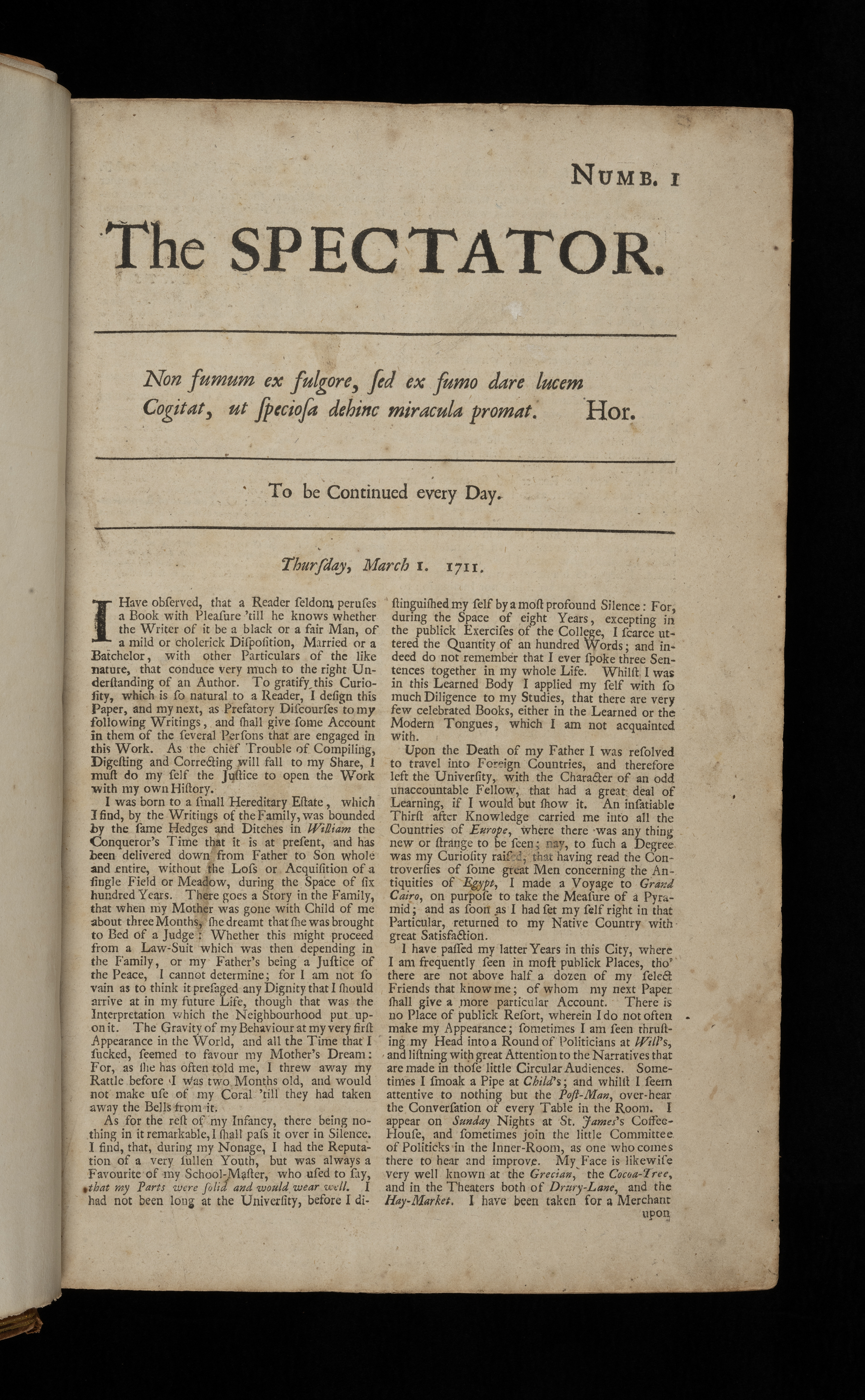

"[The Spectator] Issue 1, Thursday, March 1, 1711"

By

Joseph Addison

The Spectator followed on the heels of The Tatler, which had run from April 12, 1709 to

December 30, 1710. Steele had taken the lead with The

Tatler, asking for help from Addison and others on occasion to

fill out the pages. But it was Addison who seems to have been the leader

for The Spectator, supplying the first issue and

many others after that. In this case, timing was everything. Addison and

his Whig party had just lost a parliamentary election towards the end of

1710. Addison was a cabinet member, at the center of government

policy-making, so he suddenly found himself kicked out of office with

time on his hands; writing for in collaboration with his old friend

Richard Steele was just the thing to keep his hand in the public

conversation. The Spectator differed in format in

significant ways from its immediate predecessor. It was published daily,

except for Sunday; The Tatler had come out three

days a week. Where The Tatler had generally had

several items in each issue, most issues of The

Spectator focused on a single topic. The new journal also had a

different framing device than the older one. Where Steele had arranged

the articles in The Tatler by the imagined

location in London from which various “correspondents” were sending him

information (theater news coming from Will's Coffee House, political

news from the St. James Coffee House, the whole thing being a parody of

the way that official newspapers published correspondence from foreign

cities), The Spectator had a fictional “club”

that would come up with ideas. Steele described its members in the

second issue: there was a country squire, Sir Roger de Coverly, a

lawyer, a businessman (Sir Andrew Freeport), a soldier (Major Sentry),

an aging libertine (Will Honeycomb), and a clergyman. Between them, the

Club represented many of the important segments of middle-class culture

in the eighteenth century. The Spectator Club never worked quite as it

seems to have been intended—relatively few issues feature it in any

central way—but it was another means by which the journal was projecting

itself as giving a voice to a variety of contemporary interests. And

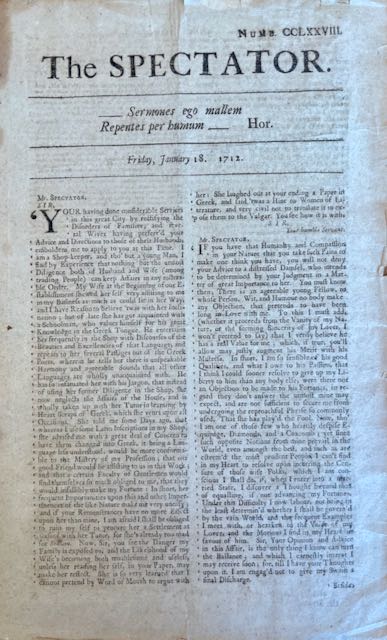

the journal occasionally referred to the coffee-house culture that

middle-class people (well, middle-class men, since women were generally not

welcome) had developed in this period, a milieu (depicted here), where men

met to socialize, gossip, talk over issues of the day, read from the

coffee-shop's stock of newspapers and journals (which were expensive enough

that individuals might not subscribe), and get their caffeine fix

satisfied.

The Spectator followed on the heels of The Tatler, which had run from April 12, 1709 to

December 30, 1710. Steele had taken the lead with The

Tatler, asking for help from Addison and others on occasion to

fill out the pages. But it was Addison who seems to have been the leader

for The Spectator, supplying the first issue and

many others after that. In this case, timing was everything. Addison and

his Whig party had just lost a parliamentary election towards the end of

1710. Addison was a cabinet member, at the center of government

policy-making, so he suddenly found himself kicked out of office with

time on his hands; writing for in collaboration with his old friend

Richard Steele was just the thing to keep his hand in the public

conversation. The Spectator differed in format in

significant ways from its immediate predecessor. It was published daily,

except for Sunday; The Tatler had come out three

days a week. Where The Tatler had generally had

several items in each issue, most issues of The

Spectator focused on a single topic. The new journal also had a

different framing device than the older one. Where Steele had arranged

the articles in The Tatler by the imagined

location in London from which various “correspondents” were sending him

information (theater news coming from Will's Coffee House, political

news from the St. James Coffee House, the whole thing being a parody of

the way that official newspapers published correspondence from foreign

cities), The Spectator had a fictional “club”

that would come up with ideas. Steele described its members in the

second issue: there was a country squire, Sir Roger de Coverly, a

lawyer, a businessman (Sir Andrew Freeport), a soldier (Major Sentry),

an aging libertine (Will Honeycomb), and a clergyman. Between them, the

Club represented many of the important segments of middle-class culture

in the eighteenth century. The Spectator Club never worked quite as it

seems to have been intended—relatively few issues feature it in any

central way—but it was another means by which the journal was projecting

itself as giving a voice to a variety of contemporary interests. And

the journal occasionally referred to the coffee-house culture that

middle-class people (well, middle-class men, since women were generally not

welcome) had developed in this period, a milieu (depicted here), where men

met to socialize, gossip, talk over issues of the day, read from the

coffee-shop's stock of newspapers and journals (which were expensive enough

that individuals might not subscribe), and get their caffeine fix

satisfied. Most importantly, The Spectator introduces a new

kind of persona, what critics call an eidolon, in

the figure of “Mr. Spectator,” in whose voice all of the essays were

composed, no matter which of the two men was the actual author. The Spectator did not invent the concept of the

eidolon, but it provided perhaps its most

influential model, one imitated over and over again in works such as

Benjamin Franklin’s “Silence Dogood” pieces in The New

England Courant (1721), Samuel Johnson’sRambler essays (1750-52), and even the Federalist essays

composed by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay to defend

the U. S. Constitution. Mr. Spectator projected himself as a civilized

man of the world, an observer looking on society like a fly on the wall.

He is well educated, but not a specialist in anything, which enables him

to comment on all sorts of things. In the course of its run, The Spectator offers essays on fashion, on

politics, on religion, on literature. Steele’s essay on Inkle and Yarico

(#11) popularized the story to eighteenth-century readers; it would

become a cultural phenomenon, with plays, musicals, and poems about the

doomed pair of lovers abounding in English-speaking culture over the

next few decades. Addison’s essays on John Milton's epic Paradise Lost and the series generally known as

“the pleasures of the imagination” became widely influential works of

literary criticism and aesthetic theory that to some extent established

a paradigm for what modern criticism could be. To be sure, this is a

very male eidolon, and it is no surprise to

discover that The Spectator’s essays are very

frequently condescending towards women readers. In the 1740s, Eliza

Haywood published a journal called The Female

Spectator http://www2.scc.rutgers.edu/spectator/haywood/, one

that forms a nice counterweight to the bluff masculinity of Addison and

Steele’s journal.

The Spectator ran from March 3, 1711 to December

6, 1712, comprising 555 issues in all. (On his own, Addison revived The Spectator briefly for a few months in 1714,

but these essays were generally not as popular.) Of these, about 250

issues each were written by Addison and Steele; Addison’s cousin Eustace

Budgell contributed a small number, as did the poet John Hughes. Over

time, we hope to add more issues of both The

Tatler and The Spectator to this digital

anthology.horace"He intends not smoke from the flame, but

fire from the smoke, so as to reveal wonderful things. Horace." Addison is

quoting here from "The Art of Poetry," a verse treatise by the Roman poet

Horace that was widely read in the eighteenth century. Addison could count

on most of his educated readers knowing the allusion, since the poem was so

widely taught in secondary schools. The joke here is that Addison is

imagining this essay as being read aloud in smoke-filled

coffeehouses.blackDark or light

skinned.cholerickA

relaxed or angry disposition.conduceContribute to.prefatoryintroductory.WilliamThe Norman warlord

who defeated the English king Harold at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and

became William I. presagedPredict or foretell.suckedbreastfedcoralThat is, his teething ring; these were often made of coral

in this period.nonageYouth or

childhood. Source: Oxford English DictionarypartsCharacteristics or elements of a person.

willsWills was a popular coffee shop. Coffee-drinking was

comparatively new to England, havinug arrived as a practice, probably from

Turkey, a few decades before. But coffee shops were everywhere in London in

the early eighteenth century, becoming popular places for men (and they were

almost-always male dominated domains) to socialize while they satisfied

their cravings for caffeine and (since smoking pipes was also popular)

nicotine. Over the next few lines, Mr. Spectator names several of the most

popular coffee shops in central London at the time.post-manone of the daily newspapers in London at that

timetheatresThe theaters

on Drury Lane and the Hay-Market were the two state-licensed playhouses in

central London. As Mr. Spectator implies here, theaters were as much places

to be seen by others as to see a play; they were intensely social spaces,

where theatergoers enjoyed the spectacle of other audience members almost as

much--and sometimes more--than they enjoyed the performances on the

stage.stock-jobbersstockbrokers, but the sense here is more pejorative

than the word is today; selling stock in private companies was comparatively

new, and looked at with suspicion by someblotsExposed

pieces in a game like backgammon, checkers, or chess. Source: Oxford English

DictionarypoliticsThe Whigs and the

Tories were the two main political factions of the day. The Spectator positioned itself as a neutral journal, and

part of the reason why Addison and Steele tried to stay anonymous was to

keep up that pretense, since they were both well known to be Whigs.characterAddison is punning here on the sense

of character as personal identity and character as a printed mark on a

page.taciturnitysilenceintimatedshared confidentiallyconcertedarranged or

contrived by two or more people working "in consert"wealwelfare and happiness

clioAddison identified the essays that he wrote with the letters C, L, I, or O,

which collectively spell out Clio, the muse of history.

Most importantly, The Spectator introduces a new

kind of persona, what critics call an eidolon, in

the figure of “Mr. Spectator,” in whose voice all of the essays were

composed, no matter which of the two men was the actual author. The Spectator did not invent the concept of the

eidolon, but it provided perhaps its most

influential model, one imitated over and over again in works such as

Benjamin Franklin’s “Silence Dogood” pieces in The New

England Courant (1721), Samuel Johnson’sRambler essays (1750-52), and even the Federalist essays

composed by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay to defend

the U. S. Constitution. Mr. Spectator projected himself as a civilized

man of the world, an observer looking on society like a fly on the wall.

He is well educated, but not a specialist in anything, which enables him

to comment on all sorts of things. In the course of its run, The Spectator offers essays on fashion, on

politics, on religion, on literature. Steele’s essay on Inkle and Yarico

(#11) popularized the story to eighteenth-century readers; it would

become a cultural phenomenon, with plays, musicals, and poems about the

doomed pair of lovers abounding in English-speaking culture over the

next few decades. Addison’s essays on John Milton's epic Paradise Lost and the series generally known as

“the pleasures of the imagination” became widely influential works of

literary criticism and aesthetic theory that to some extent established

a paradigm for what modern criticism could be. To be sure, this is a

very male eidolon, and it is no surprise to

discover that The Spectator’s essays are very

frequently condescending towards women readers. In the 1740s, Eliza

Haywood published a journal called The Female

Spectator http://www2.scc.rutgers.edu/spectator/haywood/, one

that forms a nice counterweight to the bluff masculinity of Addison and

Steele’s journal.

The Spectator ran from March 3, 1711 to December

6, 1712, comprising 555 issues in all. (On his own, Addison revived The Spectator briefly for a few months in 1714,

but these essays were generally not as popular.) Of these, about 250

issues each were written by Addison and Steele; Addison’s cousin Eustace

Budgell contributed a small number, as did the poet John Hughes. Over

time, we hope to add more issues of both The

Tatler and The Spectator to this digital

anthology.horace"He intends not smoke from the flame, but

fire from the smoke, so as to reveal wonderful things. Horace." Addison is

quoting here from "The Art of Poetry," a verse treatise by the Roman poet

Horace that was widely read in the eighteenth century. Addison could count

on most of his educated readers knowing the allusion, since the poem was so

widely taught in secondary schools. The joke here is that Addison is

imagining this essay as being read aloud in smoke-filled

coffeehouses.blackDark or light

skinned.cholerickA

relaxed or angry disposition.conduceContribute to.prefatoryintroductory.WilliamThe Norman warlord

who defeated the English king Harold at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and

became William I. presagedPredict or foretell.suckedbreastfedcoralThat is, his teething ring; these were often made of coral

in this period.nonageYouth or

childhood. Source: Oxford English DictionarypartsCharacteristics or elements of a person.

willsWills was a popular coffee shop. Coffee-drinking was

comparatively new to England, havinug arrived as a practice, probably from

Turkey, a few decades before. But coffee shops were everywhere in London in

the early eighteenth century, becoming popular places for men (and they were

almost-always male dominated domains) to socialize while they satisfied

their cravings for caffeine and (since smoking pipes was also popular)

nicotine. Over the next few lines, Mr. Spectator names several of the most

popular coffee shops in central London at the time.post-manone of the daily newspapers in London at that

timetheatresThe theaters

on Drury Lane and the Hay-Market were the two state-licensed playhouses in

central London. As Mr. Spectator implies here, theaters were as much places

to be seen by others as to see a play; they were intensely social spaces,

where theatergoers enjoyed the spectacle of other audience members almost as

much--and sometimes more--than they enjoyed the performances on the

stage.stock-jobbersstockbrokers, but the sense here is more pejorative

than the word is today; selling stock in private companies was comparatively

new, and looked at with suspicion by someblotsExposed

pieces in a game like backgammon, checkers, or chess. Source: Oxford English

DictionarypoliticsThe Whigs and the

Tories were the two main political factions of the day. The Spectator positioned itself as a neutral journal, and

part of the reason why Addison and Steele tried to stay anonymous was to

keep up that pretense, since they were both well known to be Whigs.characterAddison is punning here on the sense

of character as personal identity and character as a printed mark on a

page.taciturnitysilenceintimatedshared confidentiallyconcertedarranged or

contrived by two or more people working "in consert"wealwelfare and happiness

clioAddison identified the essays that he wrote with the letters C, L, I, or O,

which collectively spell out Clio, the muse of history.To be Continued every Day.

I HAVE observed, that a Reader seldom peruses a Book with Pleasure 'till he knows whether the Writer of it be a black or a fair ManblackblackDark or light skinned., of a mild or cholerick DispositioncholerickcholerickA relaxed or angry disposition., Married or a Batchelor, with other Particulars of the like nature, that conduceconduceconduceContribute to. very much to the right Understanding of an Author. To gratify this Curiosity, which is so natural to a Reader, I design this Paper, and my next, as Prefatoryprefatoryprefatoryintroductory. Discourses to my following Writings, and shall give some Account in them of the several persons that are engaged in this Work. As the chief trouble of Compiling, Digesting, and Correcting will fall to my Share, I must do myself the Justice to open the Work with my own History.

I was born to a small Hereditary Estate, which according to the tradition of the village where it lies, was bounded by the same Hedges and Ditches in William the Conqueror'sWilliamWilliamThe Norman warlord who defeated the English king Harold at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and became William I. Time that it is at present, and has been delivered down from Father to Son whole and entire, without the Loss or Acquisition of a single Field or Meadow, during the Space of six hundred Years. There runs a Story in the Family, that when my Mother was gone with Child of me about three Months, she dreamt that she was brought to Bed of a Judge. Whether this might proceed from a Law-suit which was then depending in the Family, or my Fathers being a Justice of the Peace, I cannot determine; for I am not so vain as to think it presagedpresagedpresagedPredict or foretell. any Dignity that I should arrive at in my future Life, though that was the Interpretation the Neighbourhood put upon it. The Gravity of my Behaviour at my very first Appearance in the World, and all the Time that I suckedsuckedsuckedbreastfed, seemed to favour my Mothers Dream: For, as she has often told me, I threw away my Rattle before I was two Months old, and would that was the Interpretation which the Neighbourhood put upon not make use of my CoralcoralcoralThat is, his teething ring; these were often made of coral in this period. till they had taken away the Bells from it.

As for the rest of my Infancy, there being nothing in it remarkable, I shall pass it over in Silence. I find that, during my NonagenonagenonageYouth or childhood. Source: Oxford English Dictionary, I had the reputation of a very sullen Youth, but was always a Favourite of my School-master, who used to say, that my partspartspartsCharacteristics or elements of a person. were solid and would wear well. I had not been long at the University, before I distinguished myself by a most profound Silence: For, during the Space of eight Years, excepting in the publick Exercises of the College, I scarce uttered the Quantity of an hundred Words; and indeed do not remember that I ever spoke three Sentences together in my whole Life. Whilst I was in this Learned Body, I applied myself with so much Diligence to my Studies, that there are very few celebrated Books, either in the Learned or the Modern Tongues, which I am not acquainted with.

Upon the Death of my Father I was resolved to travel into Foreign Countries, and therefore left the University, with the Character of an odd unaccountable Fellow, that had a great deal of Learning, if I would but show it. An insatiable Thirst after Knowledge carried me into all the Countries of Europe, in which there was any thing new or strange to be seen; nay, to such a Degree was my curiosity raised, that having read the controversies of some great Men concerning the Antiquities of Egypt, I made a Voyage to Grand Cairo, on purpose to take the Measure of a Pyramid; and, as soon as I had set my self right in that Particular, returned to my Native Country with great Satisfaction.

I have passed my latter Years in this City, where I am frequently seen in most publick Places, tho there are not above half a dozen of my select Friends that know me; of whom my next Paper shall give a more particular Account. There is no place of general Resort wherein I do not often make my appearance; sometimes I am seen thrusting my Head into a Round of Politicians at WillswillswillsWills was a popular coffee shop. Coffee-drinking was comparatively new to England, havinug arrived as a practice, probably from Turkey, a few decades before. But coffee shops were everywhere in London in the early eighteenth century, becoming popular places for men (and they were almost-always male dominated domains) to socialize while they satisfied their cravings for caffeine and (since smoking pipes was also popular) nicotine. Over the next few lines, Mr. Spectator names several of the most popular coffee shops in central London at the time., and listening with great Attention to the Narratives that are made in those little Circular Audiences. Sometimes I smoak a Pipe at Childs; and, while I seem attentive to nothing but the Post-manpost-manpost-manone of the daily newspapers in London at that time, over-hear the Conversation of every Table in the Room. I appear on Sunday nights at St. James's Coffee House, and sometimes join the little Committee of Politicks in the Inner-Room, as one who comes there to hear and improve. My Face is likewise very well known at the Grecian, the Cocoa-Tree, and in the Theaters both of Drury Lane and the Hay-MarkettheatrestheatresThe theaters on Drury Lane and the Hay-Market were the two state-licensed playhouses in central London. As Mr. Spectator implies here, theaters were as much places to be seen by others as to see a play; they were intensely social spaces, where theatergoers enjoyed the spectacle of other audience members almost as much--and sometimes more--than they enjoyed the performances on the stage.. I have been taken for a Merchant