Headnote for Alexander Pope

By

John O'Brien

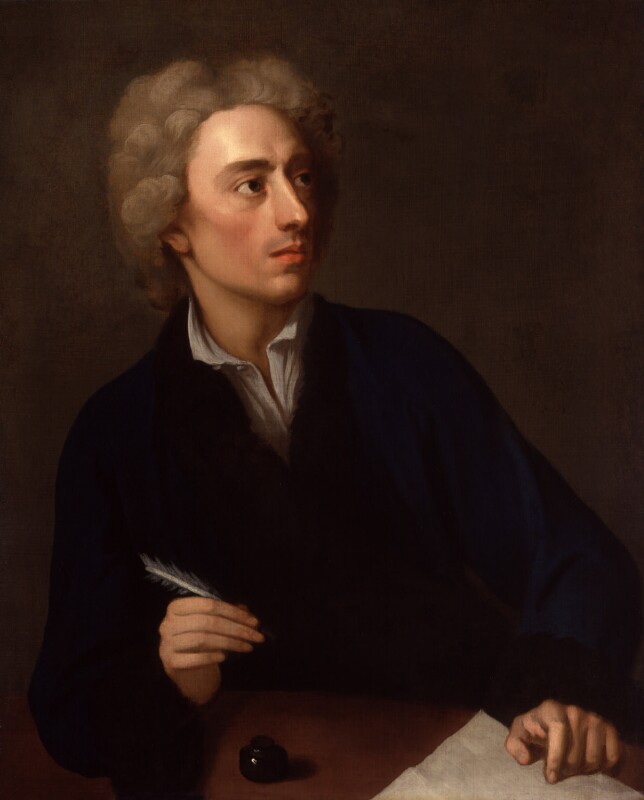

Source: Alexander Pope, by Michael Dahl, around 1727 (National Portrait Gallery, London)

Alexander Pope (1688-1744) was the greatest English poet of the eighteenth century, and one of the greatest of all the poets who have written in the English language. Poets, critics, and general readers since Pope’s own day have recognized just how spectacularly talented he was as a crafter of verse, his sheer skill with the language. And from the start, people also noticed how ambitious he was, how fully he willed himself into becoming a great poet. From his early twenties, when poems like An Essay on Criticism and The Rape of the Lock established him as the most vibrant and interesting young poet of the era, Pope has been considered to be a great writer and the most representative poet of the entire literary period between the works of John Milton and the emergence of the movement called Romanticism at the end of the eighteenth century.

Source: Alexander Pope, by Michael Dahl, around 1727 (National Portrait Gallery, London)

Alexander Pope (1688-1744) was the greatest English poet of the eighteenth century, and one of the greatest of all the poets who have written in the English language. Poets, critics, and general readers since Pope’s own day have recognized just how spectacularly talented he was as a crafter of verse, his sheer skill with the language. And from the start, people also noticed how ambitious he was, how fully he willed himself into becoming a great poet. From his early twenties, when poems like An Essay on Criticism and The Rape of the Lock established him as the most vibrant and interesting young poet of the era, Pope has been considered to be a great writer and the most representative poet of the entire literary period between the works of John Milton and the emergence of the movement called Romanticism at the end of the eighteenth century.

What, exactly, does it mean, though, to say that Pope was great and significant? What is “greatness,” anyway? This is not an easy question to answer, because it gets at questions of taste that are always going to be to some degree subjective, and to some degree determined by where you are in history. Works believed to be great in one era or context may seem trite in another, and it is fair to say that the kind of poetry that Pope wrote, with tightly-controlled rhymed heroic couplets, has not been in fashion with readers or critics for a couple of hundred years. And because of that fact, Pope and the poetry of this entire period is less accessible to us than it ought to be. We read less poetry than did eighteenth-century readers and even those who do read poetry in our times are simply not used to verse like this. The end result is that it is hard for us to see what contemporaries recognized in Pope, what they found so striking, and what caused them to admire his works.

Unlike us, eighteenth-century readers were used to reading lots of poetry in heroic couplets–it was the dominant form of poetry in English throughout the century. And no writer in English was better at writing heroic couplets than Pope. Again and again, Pope startles the reader by coming up with a wholly original way of composing his lines, of setting up his rhymes, of ordering his words perfectly such that the crucial words seem to fall into place as if there were no other way that they could be arranged. For all that Pope’s heroic couplets are artificial–no one speaks this way, after all–Pope consistently makes it feel as though the words could only be arranged in the order in which he puts them; sound follows sense to an extent that very few other poets of the period were able to achieve. We know from the surviving manuscripts of his poems that this effect–of making a very artificial form seem entirely natural, as if you’re listening to conversation rather than declamation–took a great deal of work. Pope revised his poems again and again, often keeping them in manuscript form, circulating among friends who offered advice, rewriting and recasting over and over, until he was satisfied enough to have them printed. And even then, Pope continued to revise almost all of his poems once they had been issued in print; most of his works were never “finished” in the sense of reaching a final, definitive state. Pope saw composing poetry as a process that never had an end, an ongoing dialogue in poetry between himself, his readers, and the age that they both lived in.

Pope was enormously ambitious–-he sought fame, recognition, and the wealth that would give a man like him--middle class, well-educated, but without the kind of family wealth or connections that he could rely upon to provide a steady income--the independence that he needed for his art. He also had a significant physical disability. Pope contracted what is called Pott's disease--essentially a form of tuberculosis that affects the spine--at the age of 12. The condition arrested his growth (in adulthood Pope was well under five feet tall), and was painful and degenerative, weakening his spine to the point where he eventually had to be laced into a corset to stand upright. It also rankled Pope that he could not be the official poet laureate because, as a Roman Catholic, he was barred from holding that kind of state-sponsored post. (And, as a Roman Catholic in a period when English people were in general prejudiced against Catholics, he had to put up with many writers who could not help but make jokes about the fact that this Catholic poet happened to be named “Pope.”) But Pope saw himself as becoming in effect, the real poet laureate of his age, speaking to contemporary events while also tailoring his career according to the careers of classical writers. He started, as the Roman poet Virgil did, writing pastoral poetry, then moved on to translating epics: Pope’s versions of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey were his most popular works in his own lifetime and were the standard translations of both poems for the rest of the century. Pope is the rare case of a person whose skills and ambition matched up. Overcoming his era's prejudices against Catholics as well as a disability that he once referred to as "this long disease, my life," Alexander Pope willed himself into the poet who dominated the verse of his own era, and who would be remembered long after that era was over.