Headnote for Julian of Norwich

By

John O'Brien

Everything that we know about the life of Julian of Norwich (c.1342-c.1416) is fascinating. But we know very few things for certain, and much of what we know comes from her written work, the text known as Revelations of Divine Love. Julian reports there that she had a terrible illness at the age of 30 and a half in May 1373, an illness so extreme that she and her family believed that she would die. A priest came to give her the last rites. Gazing at the crucifix that the priest was holding, Julian began to experience what would become a series of sixteen visions of the crucifixion of Jesus, visions that she describes and interprets in the Revelations. Probably not long after the visions, she composed (or told to a scribe; we cannot be sure) a brief account of them, in what is now known as the “Short Text.” About twenty years later, after reflecting on these visions, she produced what is known as the “Long Text,” which is what we include in this anthology. This is the first work in the English language that we know to have been written by a woman.

We also know that at some point after her mystical experience in 1373, Julian became an “anchoress,” living in a cell in St. Julian’s Church in Norwich, England, a cell in which she spent the rest of her life mostly in meditation and prayer. (It is possible then, that “Julian” is a name she took after taking up her life as an anchoress in that church, but it was a common enough name in the period that it might just be a coincidence.) There are a number of wills from the 1390s to the 1410s where people left money to help support her. And we know that Margery Kempe, another English mystic, visited her in 1413, and noted that Julian was well known for giving good spiritual counsel. The last reference to Julian is in a will from 1416, so she must have died sometime after that, having lived into her 70s, a good age in that period.

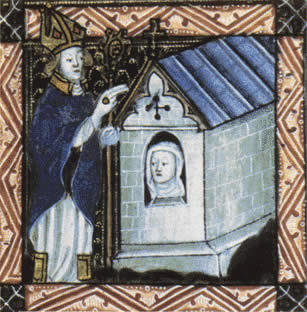

Source: A bishop blessing an anchoress, circa 1400. Corpus Cristi College, Cambridge (Wikimedia Commons)

Source: A bishop blessing an anchoress, circa 1400. Corpus Cristi College, Cambridge (Wikimedia Commons)

As an anchoress, Julian would have had a high status. Anchorites (men) and anchoresses (women) were understood to be withdrawing themselves from the world to undertake a life of prayer and meditation on behalf of their communities. She would have gone through a ceremony led by a bishop who would have recited prayers that were usually offered at funerals, marking her symbolic death in the secular world and her new life apart from it. Anchoresses were sealed in their cells for the rest of their lives, with only a small window through which they could view the Mass, and another window or grate with which they could receive food and communicate with others. Servants brought them food and tended to their other physical needs. People like Margery Kempe came to anchoresses like Julian for religious advice, so it is not like they never communicated with others. But except for such occasional visits, anchoresses devoted themselves to solitary prayer.

Julian’s Revelations of Divine Love is an extraordinary work of Christian mysticism and theology. It imagines the events of Jesus’s crucifixion in amazing detail, and interprets the suffering of Jesus as a testimony of God’s love for humanity. The God of Julian's Revelations is a loving God, not the stern and distant figure that was often imagined by theologians in this period. In the end, Jesus assures Julian, "all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well,” a famous line that captures some of the optimism of the book, the belief that through prayer, people can redeem the fallen state of humanity and help everyone share in the divine gift of eternal life.