Headnote for Olaudah Equiano

By

John O'Brien

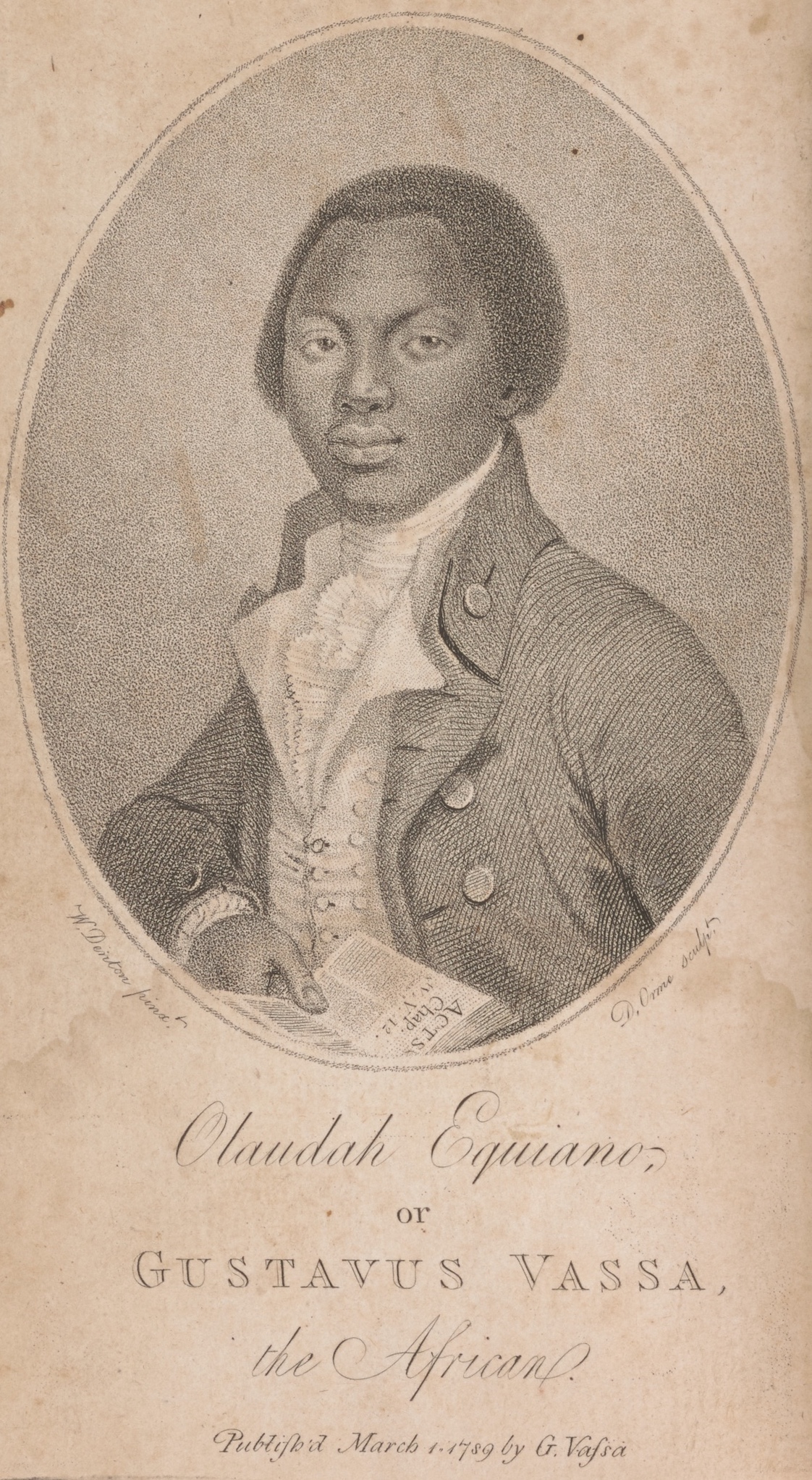

Source: Frontispiece portrait of Equiano, from 'The Interesting Narrative'

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano is

the first example in English of the slave narrative, the autobiography written by

one of the millions of persons from Africa or of African descent who were enslaved

in the Atlantic world between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries. Equiano’s

is an extraordinary memoir, telling the author’s life story from his birth in west

Africa, in what was then known as Essaka (in what is now the nation of Nigeria), his

kidnapping, the middle passage across the Atlantic ocean in a slave ship, the

brutality of the slave system in the American colonies in the Caribbean, the

mainland of North America, and at sea. Equiano also tells the story of his life as a

free man of color; after he was finally able to purchase his freedom in 1766, he was

a merchant, a seaman, a musician, a barber, a civil servant, and, finally, a writer

who took to the pages of London newspapers to argue on behalf of his fellow

Afro-Britons before publishing this account of his life.

Source: Frontispiece portrait of Equiano, from 'The Interesting Narrative'

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano is

the first example in English of the slave narrative, the autobiography written by

one of the millions of persons from Africa or of African descent who were enslaved

in the Atlantic world between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries. Equiano’s

is an extraordinary memoir, telling the author’s life story from his birth in west

Africa, in what was then known as Essaka (in what is now the nation of Nigeria), his

kidnapping, the middle passage across the Atlantic ocean in a slave ship, the

brutality of the slave system in the American colonies in the Caribbean, the

mainland of North America, and at sea. Equiano also tells the story of his life as a

free man of color; after he was finally able to purchase his freedom in 1766, he was

a merchant, a seaman, a musician, a barber, a civil servant, and, finally, a writer

who took to the pages of London newspapers to argue on behalf of his fellow

Afro-Britons before publishing this account of his life.

Equiano’s book offered the first full description of the middle passage, a description harrowing in its sensory vividness:

The stench of the hold while we were on the coast was so intolerably loathsome, that it was dangerous to remain there for any time, and some of us had been permitted to stay on the deck for the fresh air; but now that the whole ship’s cargo were confined together, it became absolutely pestilential. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the improvident avarice, as I may call it, of their purchasers. This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable. Happily perhaps for myself I was soon reduced so low here that it was thought necessary to keep me almost always on deck; and from my extreme youth I was not put in fetters. In this situation I expected every hour to share the fate of my companions, some of whom were almost daily brought upon deck at the point of death, which I began to hope would soon put an end to my miseries. Often did I think many of the inhabitants of the deep much more happy than myself. I envied them the freedom they enjoyed, and as often wished I could change my condition for theirs. Every circumstance I met with served only to render my state more painful, and heighten my apprehensions, and my opinion of the cruelty of the whites.

Equiano’s book is both a personal story and a powerful item of testimony about the larger system of slave-trading that supported the economic system through which Britain developed a global empire. Spanning the transatlantic world, Equiano’s story powerfully captures the lived experience of slavery in the eighteenth century through the eyes of an observer with almost unbelievable resourcefulness and resilience. The book is also interesting as a literary document. Equiano is clearly familiar with the genre of the spiritual autobiography, the Puritan form of self-examination and life writing that shaped works such as Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, and he also cites English poets such as John Milton and Alexander Pope, demonstrating his mastery of the canon of great English literature. Equiano’s Interesting Narrative is one of the most absorbing, indeed interesting first-person stories of the entire century, a work that both narrates a remarkable set of experiences and shrewdly shapes it through the forms available to its author to make the case for the abolition of the slave trade.

It is important to note, however, that in the last two decades, scholars have raised doubts about the truth of some parts of Equiano’s Interesting Narrative. Vincent Carretta, probably the leading scholar in the United States on Equiano’s work and life, has discovered documents such as Royal Navy muster rolls where Equiano (who was identified for much of his adult life as “Gustavus Vassa,” the name given to him by Michael Pascal, his first owner) is recorded as having been born in colonial South Carolina. So too does the record of his baptism into Christianity in 1759 at St. Margaret’s Church in London. It is possible, then, that Equiano is misrepresenting his place of birth, perhaps because he believed that his story would be more compelling if he were able to describe himself as a native-born African. Other scholars have suggested that there may be other reasons to account for the discrepancy; Equiano was not responsible for creating these records, and there may be all sorts of reasons why the people who were in charge of these documents, or he, might have decided not to have identified him as having born in Africa, some of which we probably cannot reconstruct from this distance. The question of where Equiano was born will probably remain unresolved until better documentary evidence or new ways of understanding the evidence that we already have become available. What no one has ever questioned is that Equiano’s Interesting Narrative is extremely accurate in its depiction of the way that the eighteenth-century slave system worked, the horrors of the middle passage, and the constant threats to their freedom and well-being experienced by free people of color, particularly in the American colonies.

The publication of the Interesting Narrative was an important event in its own right. First issued in the spring of 1789, the book was timed to coincide with a Parliamentary initiative to end Britain’s participation in the international slave trade. This was the goal of the first abolitionist movement, a movement originating largely with Quakers that was adopted and secularized by a combination of evangelical and more secular writers in the 1780s and that found its institutional centers of gravity in the largely white Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, founded in 1787, and in the Sons of Africa, a society of free persons of African descent in Great Britain in which Equiano had a leadership role. This generation of abolitionists focused on ending the slave trade rather than for the ending of slavery as an institution and the emancipation of all enslaved people in large part because they believed it to be unviable politically. Rather, they focused on ending the slave trade, arguing that if slave owners were unable to purchase new slaves kidnapped and transported from Africa, they would be forced to be more benevolent to their own slaves, and the institution would be forced to reform itself. Equiano was active in these abolitionist circles, and his book in part serves the function of a petition to Parliament to end the slave trade, with the names of the book’s subscribers identifying themselves as allies and co-petitioners in the cause. The first edition begins by including the names of 311 people who subscribed to it and thereby subsidized its printing, and later editions (nine in all in Equiano’s lifetime, a testimony to the great demand for his book) added more, eventually totalling over a thousand, as more people wanted both to own the book and to ally themselves with the abolitionist cause. Subscribers were thus taking an interest in this book in the financial sense, publicly advancing resources to support Equiano and the movement that the book was published to support. The Interesting Narrative was first printed in the United States in New York in 1791 (without Equiano’s permission, as was typical for books reprinted from Britain in the early decades of the new republic), and was widely reprinted throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.

Equiano toured throughout the British Isles in the early 1790s, making speaking engagements to promote the abolitionist cause, and also to support sales of his book, for which he had retained copyright. This turned out to be a smart business decision; he made a fair amount of money from sales of the Interesting Narrative. Equiano married a woman named Susannah Cullen in 1792; they had two daughters, only one of whom survived to adulthood. But neither Olaudah or Susannah was able to enjoy their married life for very long. Susanna died in 1796 and Olaudah died in 1797. The abolitionist cause to which the Interesting Narrative was a major contributor succeeded only after his death, as Britain ended its participation in the slave trade in 1807, and finally abolished slavery in its colonial holdings in 1833. Slavery in the United States continued until the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863.