A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

By

Mary Wollstonecraft

A

VINDICATION

OF THE

RIGHTS OF WOMAN:

WITH

STRICTURES

ON

POLITICAL AND MORAL SUBJECTS

BY MARY WOLLSTONECRAFTwollstonecraft

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR J. JOHNSON, No.71, ST. PAUL’S CHURCH YARD.johnson

1792. 1 INTRODUCTION

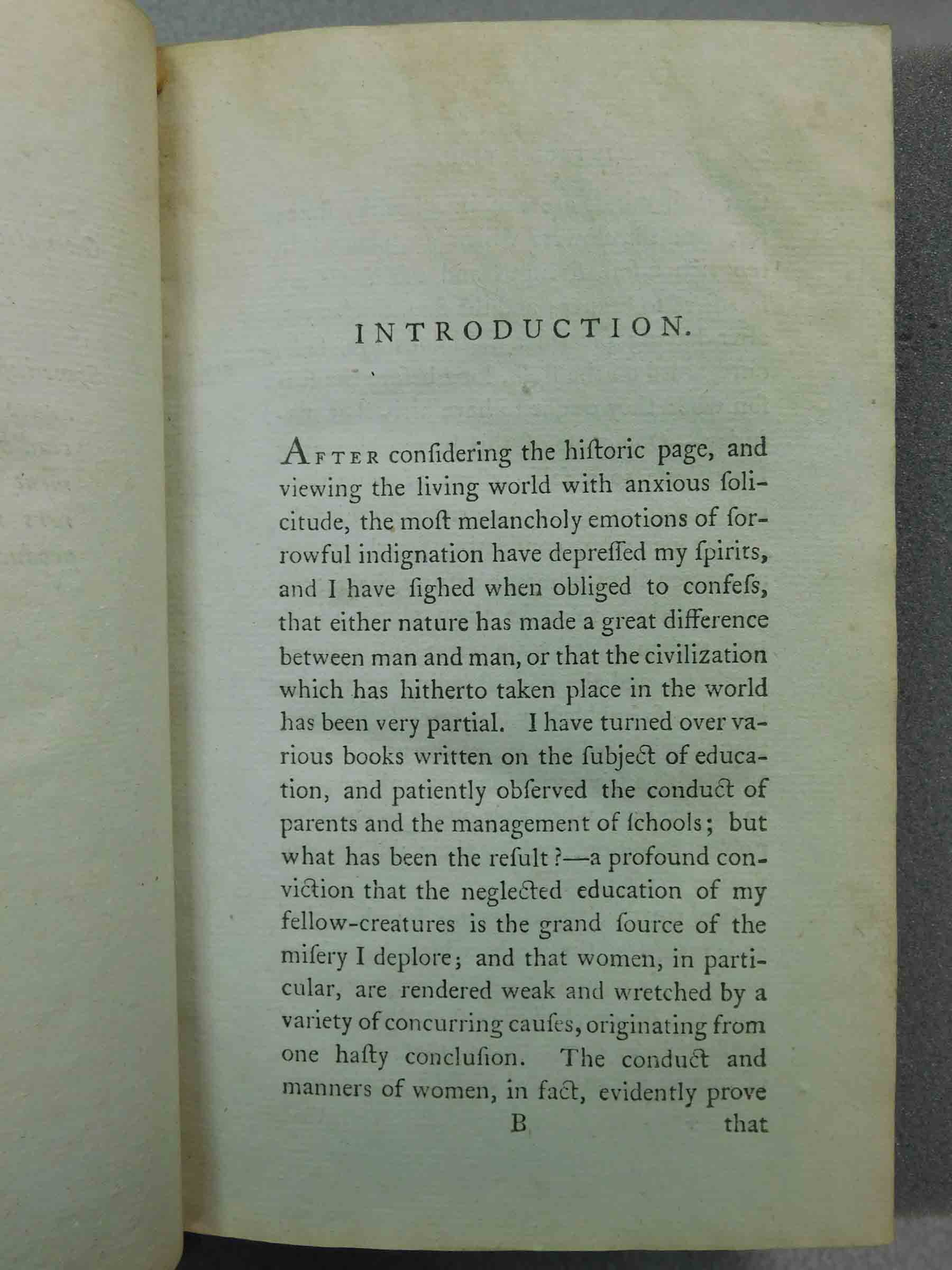

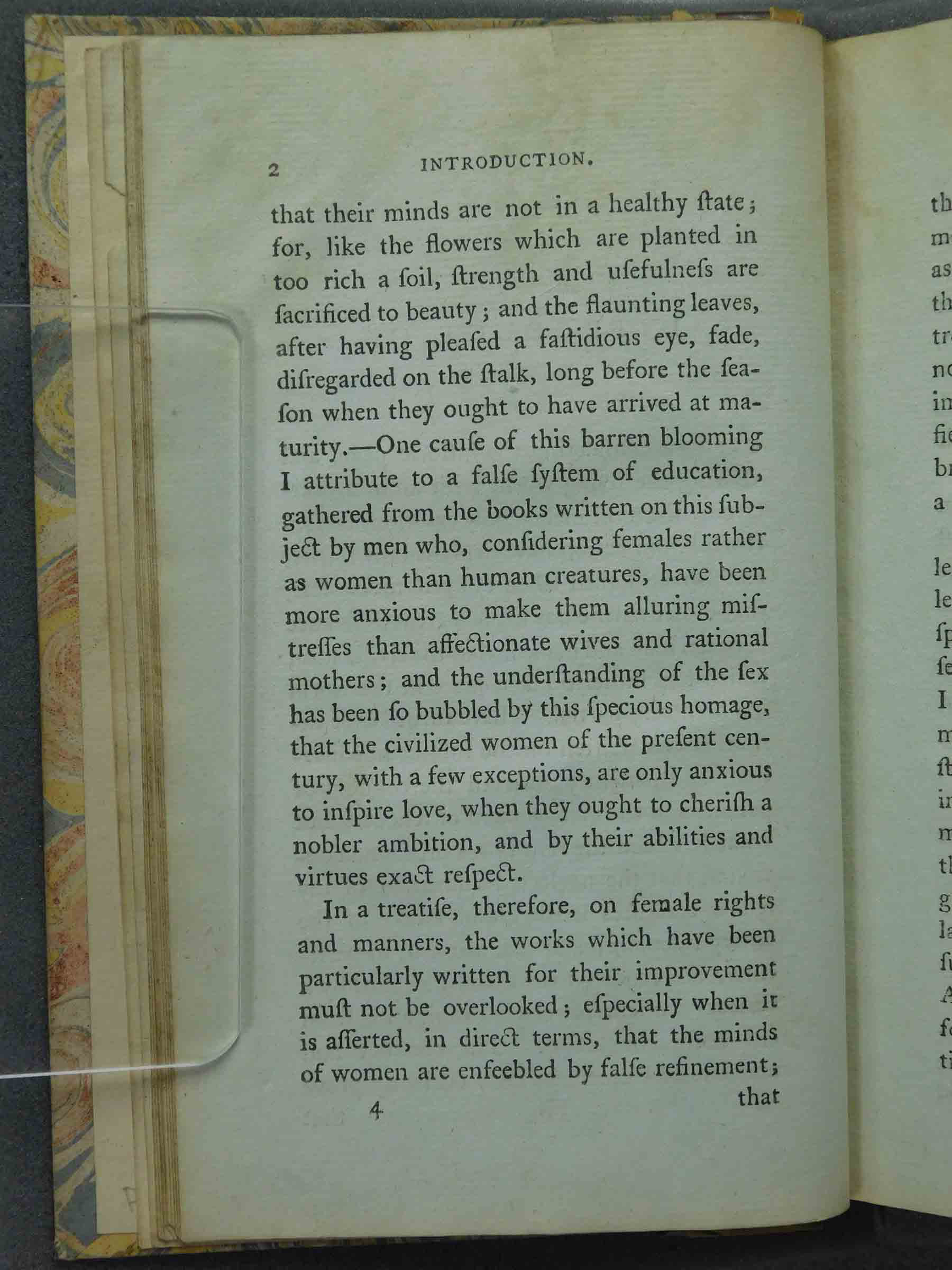

AFTER considering the historic page, and viewing the living world with anxious solicitude, the most melancholy emotions of sorrowful indignation have depressed my spirits, and I have sighed when obligated to confess, that either nature has made a great difference between man and man, or that the civilization which has hitherto taken place in the world has been very partial. I have turned over various books written on the subject of education, and patiently observed the conduct of parents and the management of schoolseducation; but what has been the result? --a profound conviction that the neglected education of my fellow-creatures is the grand source of the misery I deplore; and that women, in particular, are rendered weak and wretched by a variety of concurring causes, originating from a hasty conclusion. The conduct and manners of women, in fact, evidently prove 2 that their minds are not in a healthy state; for, like the flowers which are planted in too rich a soil, strength and usefulness are sacrificed to beauty; and the flaunting leaves, after having pleased a fastidious eye, fade, disregarded on the stalk, long before the season when they ought to have arrived at maturity.--One cause of this barren blooming I attribute to a false system of education, gathered from the books written on this subject by men, who considering females rather than human creatures, have been more anxious to make them alluring mistresses than rational wives; and the understanding of sex has been so bubbledbubbled by this specious homage, that the civilized women of the present century, with a few exceptions, are only anxious to inspire love, when they ought to cherish a nobler ambition, and by their abilities and virtues exact respect.

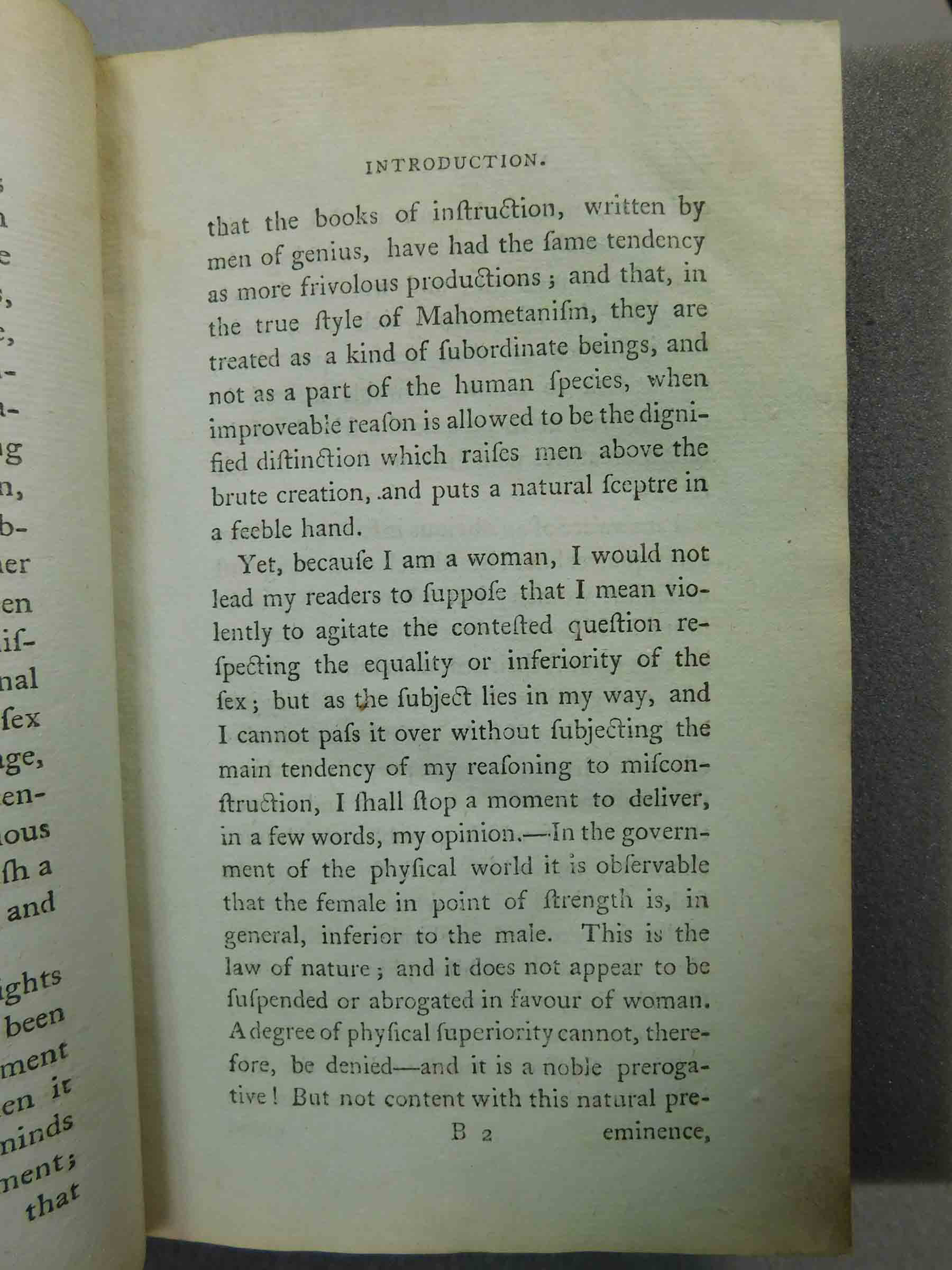

In a treatise, therefore, on female rights and manners, the works which have been particularly written for their improvementconduct must not be overlooked; especially when it is asserted, in direct terms, that the minds of women are enfeebled by false refinement; 3 that the books of instruction, written by men of genius, have had the same tendency as more frivolous productions; and that, in the true style of Mahometanismmahometanism, they are only considered as females, and not as a part of the human species, when improvable reason is allowed to be the dignified distinction which raises men above the brute creation, and puts a natural sceptre in a feeble hand.

Yet, because I am a woman, I would not lead my reader to suppose that I mean violently to agitate the contested question respecting the equality or inferiority of the sex; but as the subject lies in my way, and I cannot pass it over without subjecting the main tendency of my reasoning to misconstruction, I shall stop a moment to deliver, in a few words, my opinion. --In the government of the physical world it is observable that the female, in general, is inferior to the male. The male pursues, the female yields--this is the law of nature; and it does not appear to be suspended or abrogated in favour of woman. This physical superiority cannot be denied--and it is a noble prerogative! But not content with this natural preeminence, 4 [break after pre-]men endeavour to sink us still lower, merely to render us alluring objects for a moment; and women, intoxicated by the adoration which men, under the influence of their senses, pay them, do not seek to obtain a durable interest in their hearts, or to become the friends of the fellow creatures who find amusement in their society.

I am aware of an obvious inference: from every quarter have I hear exclamations against masculine women; but where are they to be found? If by this appellation men mean to inveigh against their ardour in hunting, shooting, and gaming, I shall most cordially join in the cry; but if it be against the imitation of manly virtuesmanly or, more properly speaking, the attainment of those talents and virtues, the exercise of which ennobles the human character, and which raise females in the scale of animal being, when they are comprehensively termed mankind; all those who view them with a philosophical eye must, I should think, wish with me, that they may every day grow more and more masculine.

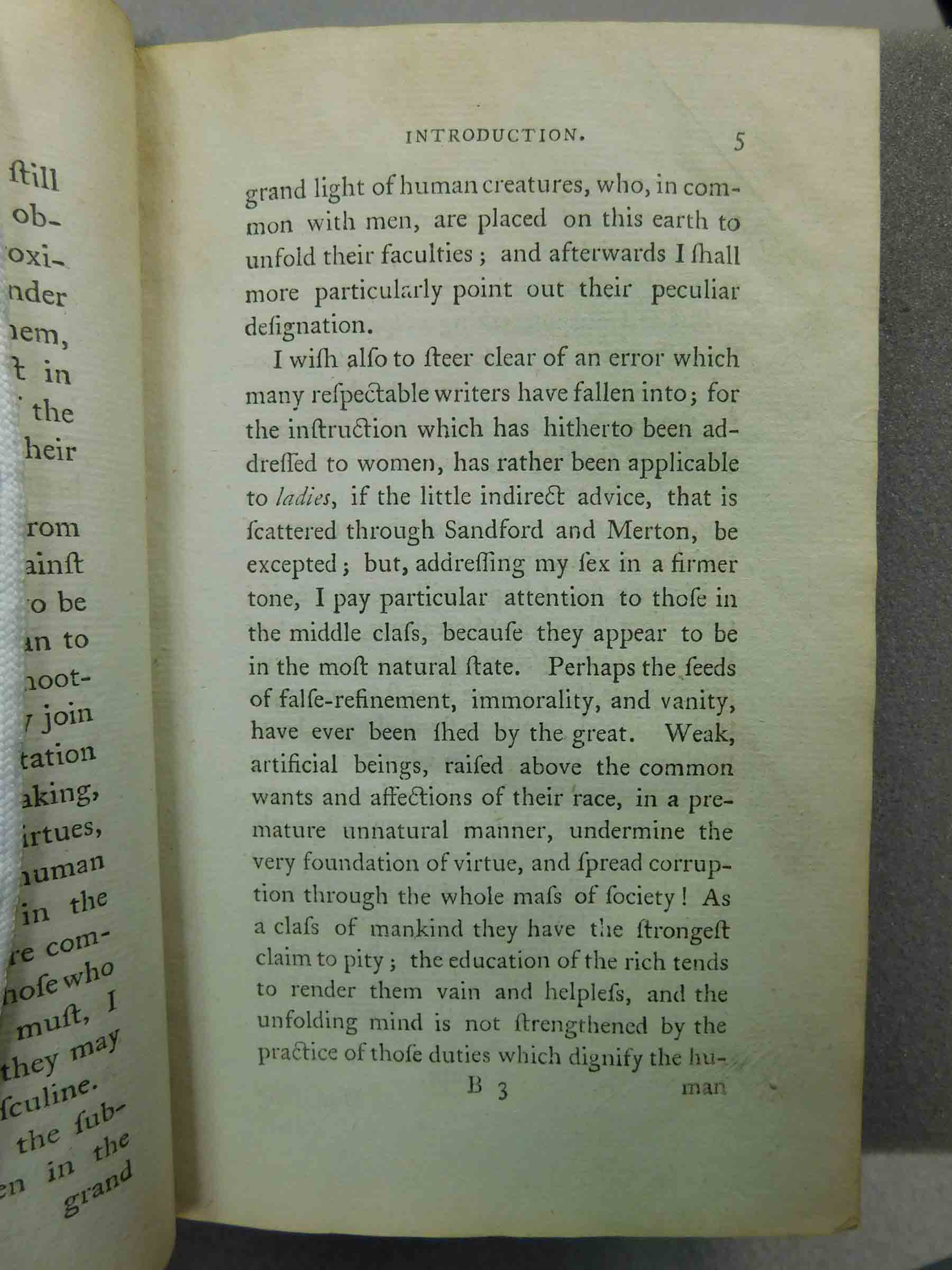

This discussion naturally divides the subject. I shall first consider women in the 5 grand light of human creatures, who, in common with men, are placed on this earth to unfold their faculties; and afterwards I shall more particularly point out their peculiar designation.

I wish also to steer clear of an error which many respectable writers have fallen into; for the instruction which has hither been addressed to women, has rather been applicable to ladies, if the little indirect advice, that is scattered through Sandford and Mertonsandford_merton, be excepted; but, addressing my sex in a firmer tone, I pay particular attention to those in the middle class, because they appear to be in the most natural state. Perhaps the seeds of false-refinement, immorality, and vanity, have ever been shed by the great. Weak, artificial beings, raised above the common wants and affections of their race, in a premature unnatural manner, undermine the very foundation of virtue, and spread corruption through the whole mass of society! As a class of mankind they have the strongest claim to pity; the education of the rich tends to render them vain and helpless, and the unfolding mind is not strengthened by the practice of those duties which dignify the human 6 [break after 'hu-'] character.—They only live to amuse themselves, and by the same law which in nature invariably produces certain effects, they soon only afford barren amusement.

But as I purpose taking a separate view of the different ranks of societyranks, and of the moral character of women, in each, this hint is, for the present, sufficient; and I have only alluded to the subject, because it appears to me to be the very essence of an introduction to give a cursory account of the contents of the work it introduces.

My own sex, I hope, will excuse me, if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their fascinating graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone. I earnestly wish to point out in what true dignity and human happiness consists—I wish to persuade women to endeavour to acquire strength, both of mind and body, and to convince them that the soft phrases, susceptibility of heart, delicacy of sentiment, and refinement of taste, are almost synonymous with epithets of weakness, and that those beings who are only the objects of pity and that kind of love, which has been termed its sister, will soon become objects of contempt.

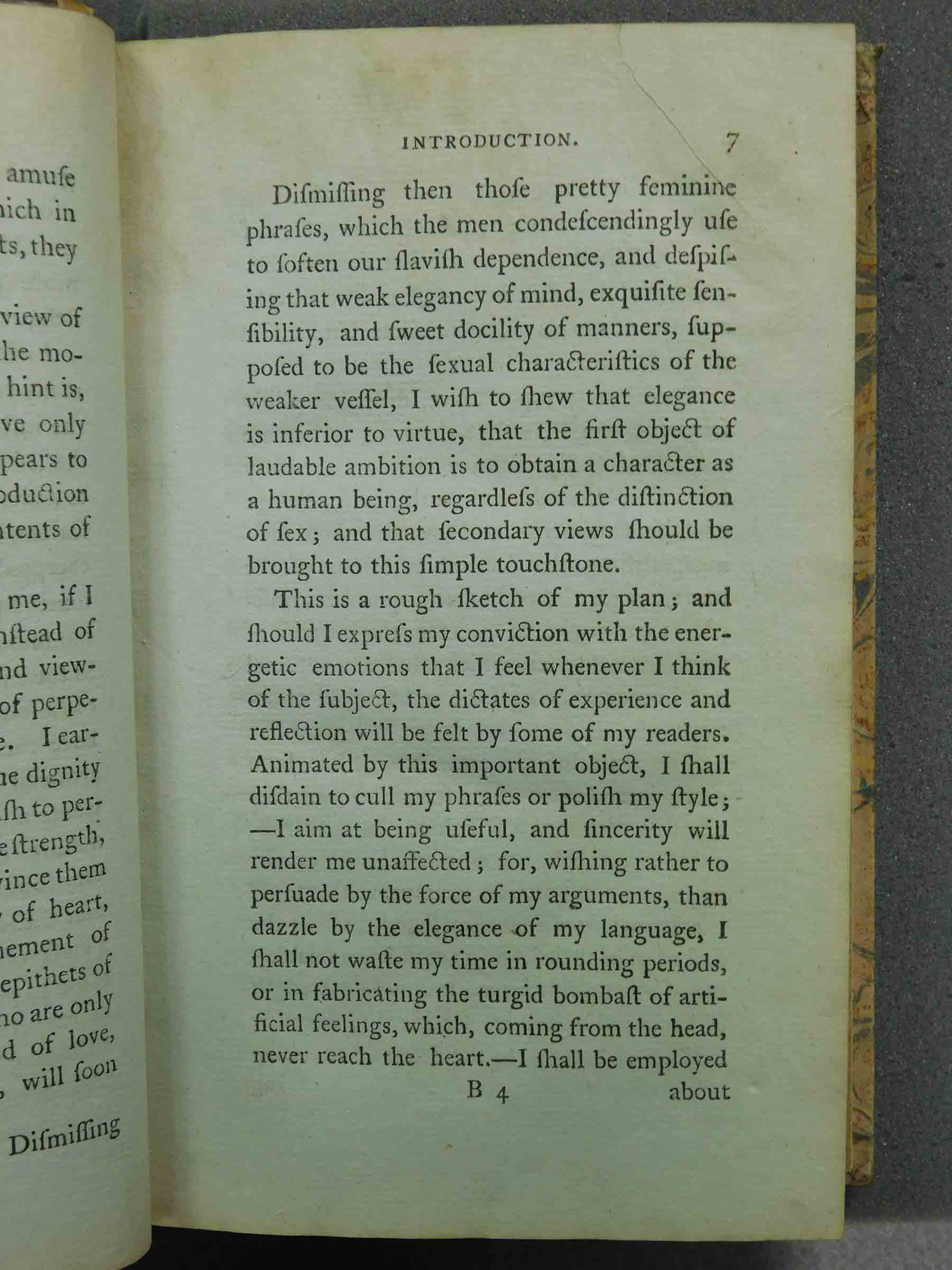

7Dismissing then those pretty feminine phrases, which the men condescendingly use to soften our slavish dependence, and despising that weak elegancy of mindelegance, exquisite sensibility, and sweet docility of manners, supposed to be the sexual characteristics of the weaker vessel, I wish to shew that elegance is inferior to virtuevirtue, that the first object of laudable ambition is to obtain a character as a human being, regardless of the distinction of sex; and that secondary views should be brought to this simple touchstone.

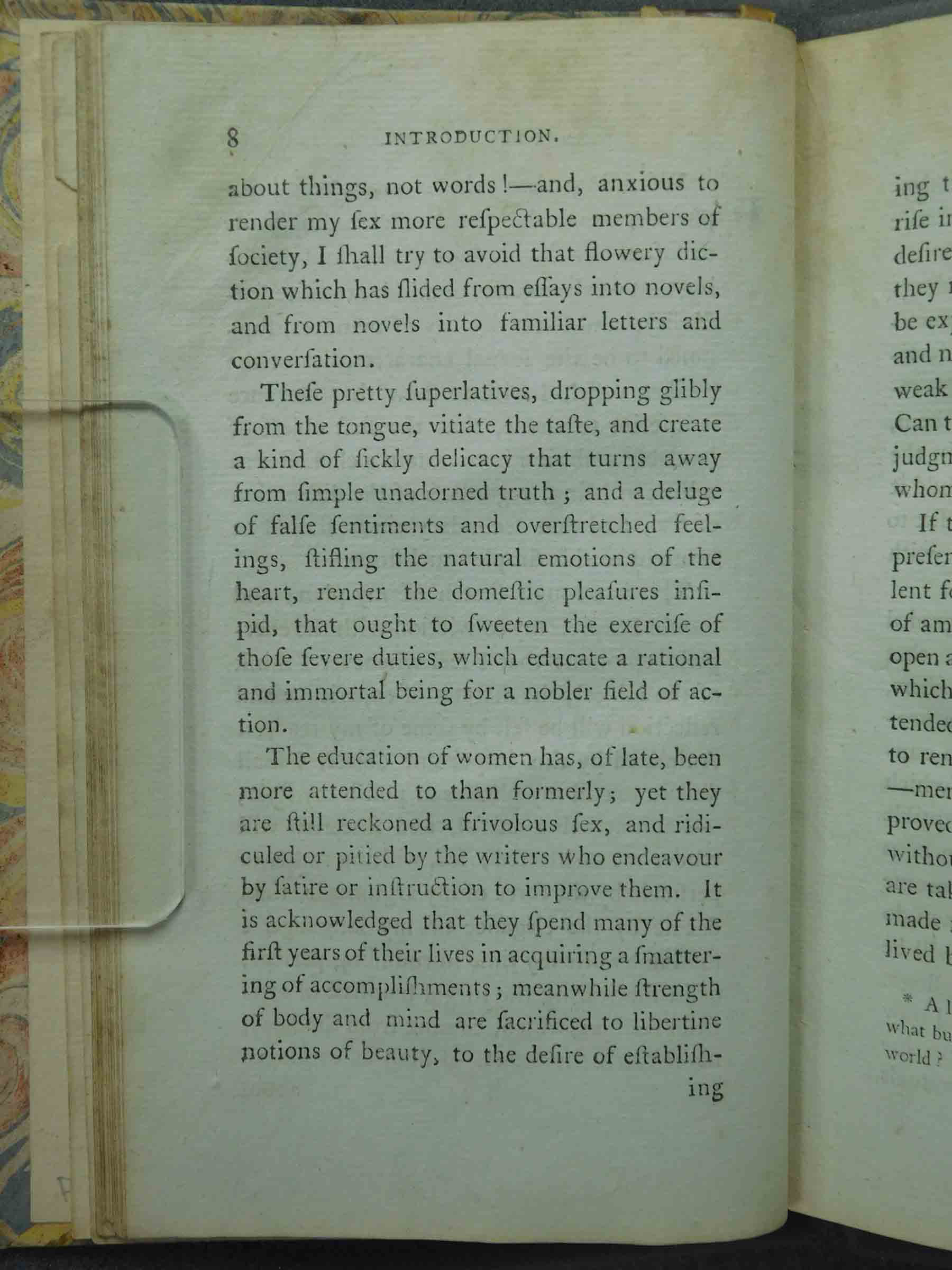

This is a rough sketch of my plan; and should I express my conviction with the energetic emotions that I feel whenever I think of the subject, the dictates of experience and reflection will be felt by some of my readers. Animated by this important object, I shall disdain to cull my phrases or polish my style;--I aim at being useful, and sincerity will render me unaffected; for, wishing rather to persuade by the force of my arguments, than dazzle by the elegance of my language, I shall not waste my time in rounding periods, or in fabricating the turgid bombast of artificial feelings, which, coming from the head, never reach the heart. – I shall be employed about 8 things, not words! – and, anxious to render my sex more respectable members of society, I shall try to avoid that flowery diction which has slided from essays into novels, and from novels into familiar letters and conversation.

These pretty nothings – these caricatures of the real beauty of sensibility, dropping glibly from the tongue, vitiate the taste, and create a kind of sickly delicacy that turns away from simple unadorned truth; and a deluge of false sentiments and overstretched feelings, stifling the natural emotions of the heart, render the domestic pleasures insipid,--that ought to sweeten the exercise of those severe duties, which educate a rational and immortal being for a nobler field of action.

The education of womenschools has, of late, been more attended to than formerly; yet they are still reckoned a frivolous sex, and ridiculed or pitied by the writers who endeavor by satire or instruction to improve them. It is acknowledged that they spend many of the first years of their lives in acquiring a smattering of accomplishments: meanwhile strength of body and mind are sacrificed to libertine notions of beauty, to the desire of establishing 9 [break after 'establish-']themselves, --the only way women can rise in the world,--by marriage. And this desire making mere animals of them, when they marry they act as such children may be expected to act: --they dress; they paint, and nickname God’s creatures. --Surely there weak beings are only fit for a seraglioseraglio! --Can they govern a family, or take care of the poor bebes whom they bring into the world?

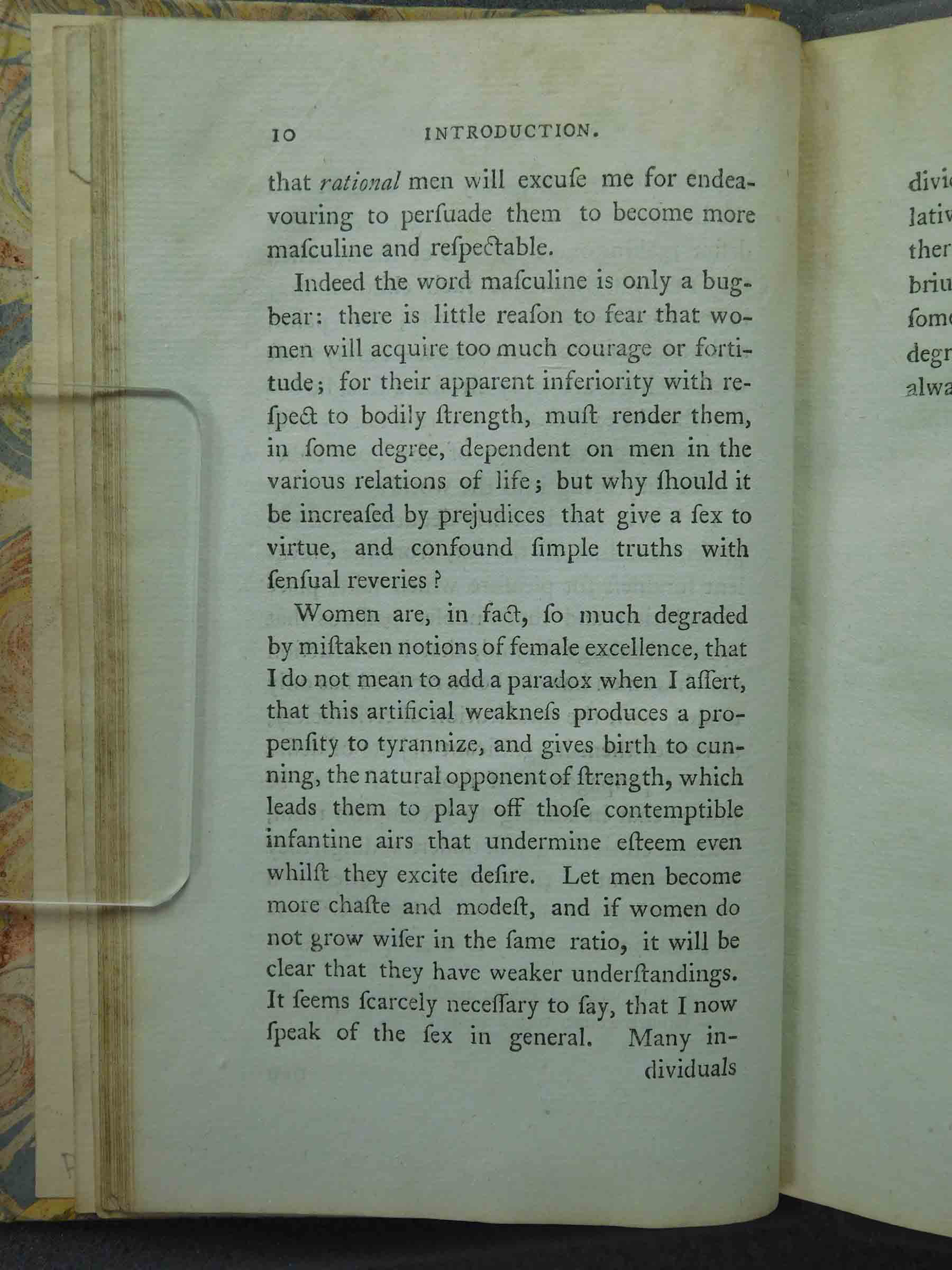

If then it can be fairly deduced from the present conduct of the sex, from the prevalent fondness for pleasure which takes place of ambition and those nobler passions that open and enlarge the soul; that the instruction which women have received has only tended, with the constitution of civil society, to render them insignificant object of desire--more propagators of fools! --if it can be proved that in aiming to accomplish them, without cultivating their understandings, they are taken out of their sphere of duties, and make ridiculous and useless when the short-lived bloom of beauty is over*auth1, I presume 10 that rational men will excuse me for endeavoring to persuade them to become more masculine and respectable.

Indeed the word masculine is only a bugbear: there is little reason to fear that women will acquire too much courage or fortitude; for their apparent inferiority with respect to bodily strength, must render them, in some degree, dependent on men in the in the various relations of life; but why should it be increased by prejudices that give a sex to virtue, and confound simple truths with sensual reveries?

Women are, in fact, so much degraded by mistaken notions of female excellence, that I do not mean to add a paradox when I assert, that this artificial weakness produces a propensity to tyrannize, and gives birth to cunning, the natural opponent of strength, which leads them to play off those contemptible infantine airs that undermine esteem even whilst they excite desire. Do not foster these prejudices, and they will naturally fall into their subordinate, yet respectable station in life. It seems scarcely necessary to say, that I now speak of the sex in general. Many individuals 11 [break after 'in-']have more sense than their male relatives; and, as nothing preponderates where there is a constant struggle for an equilibrium, without it has naturally more gravity, some women govern their husbands without degrading themselves, because intellect will always govern.

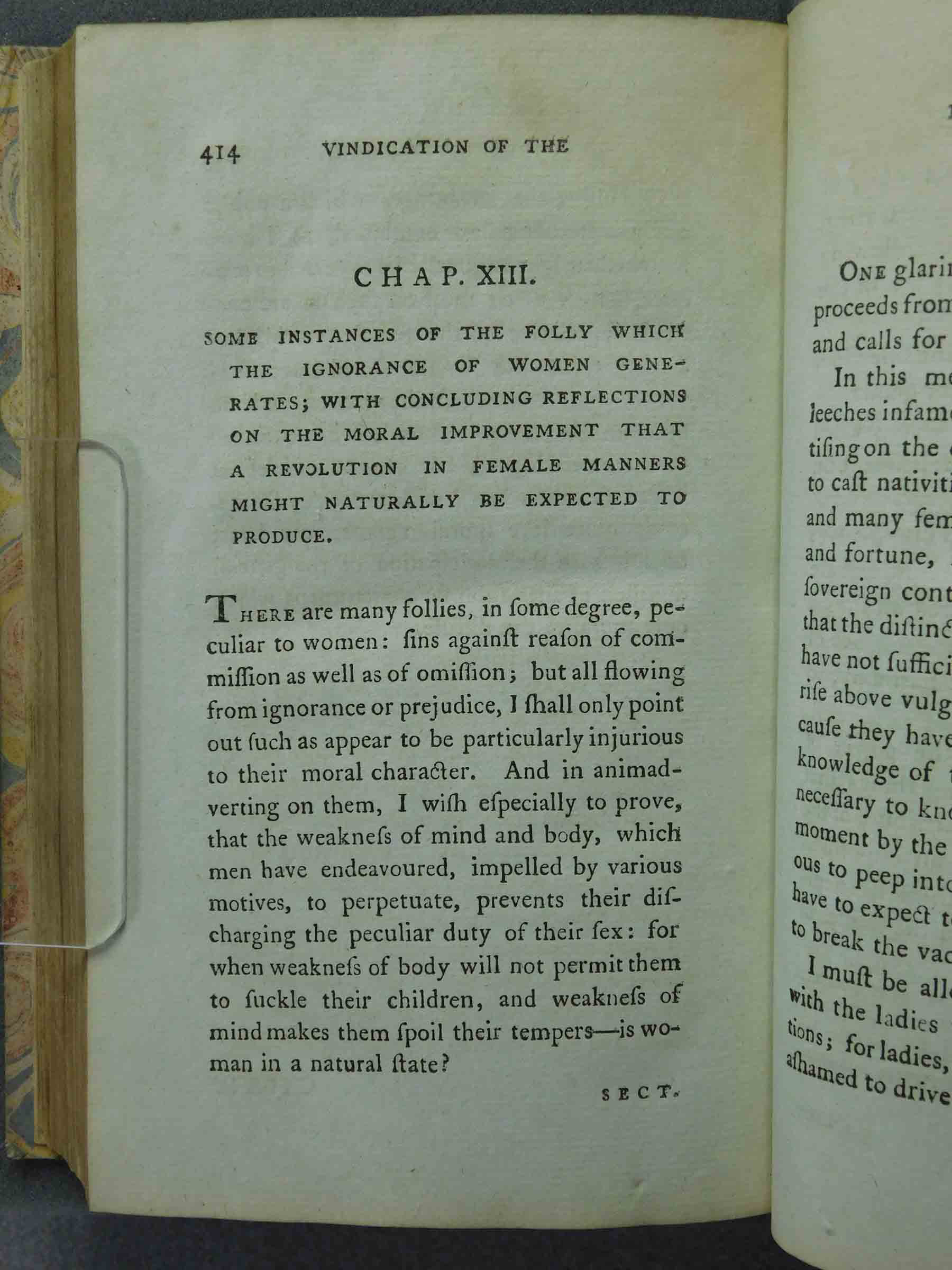

414 CHAP. XIIISOME INSTANCES OF THE FOLLY WHICH THE IGNORANCE OF WOMEN GENERATES; WITH CONCLUDING REFLECTIONS ON THE MORAL IMPROVEMENT THAT A REVOLUTION IN FEMALE MANNERS MIGHT NATURALLY BE EXPECTED TO PRODUCE.

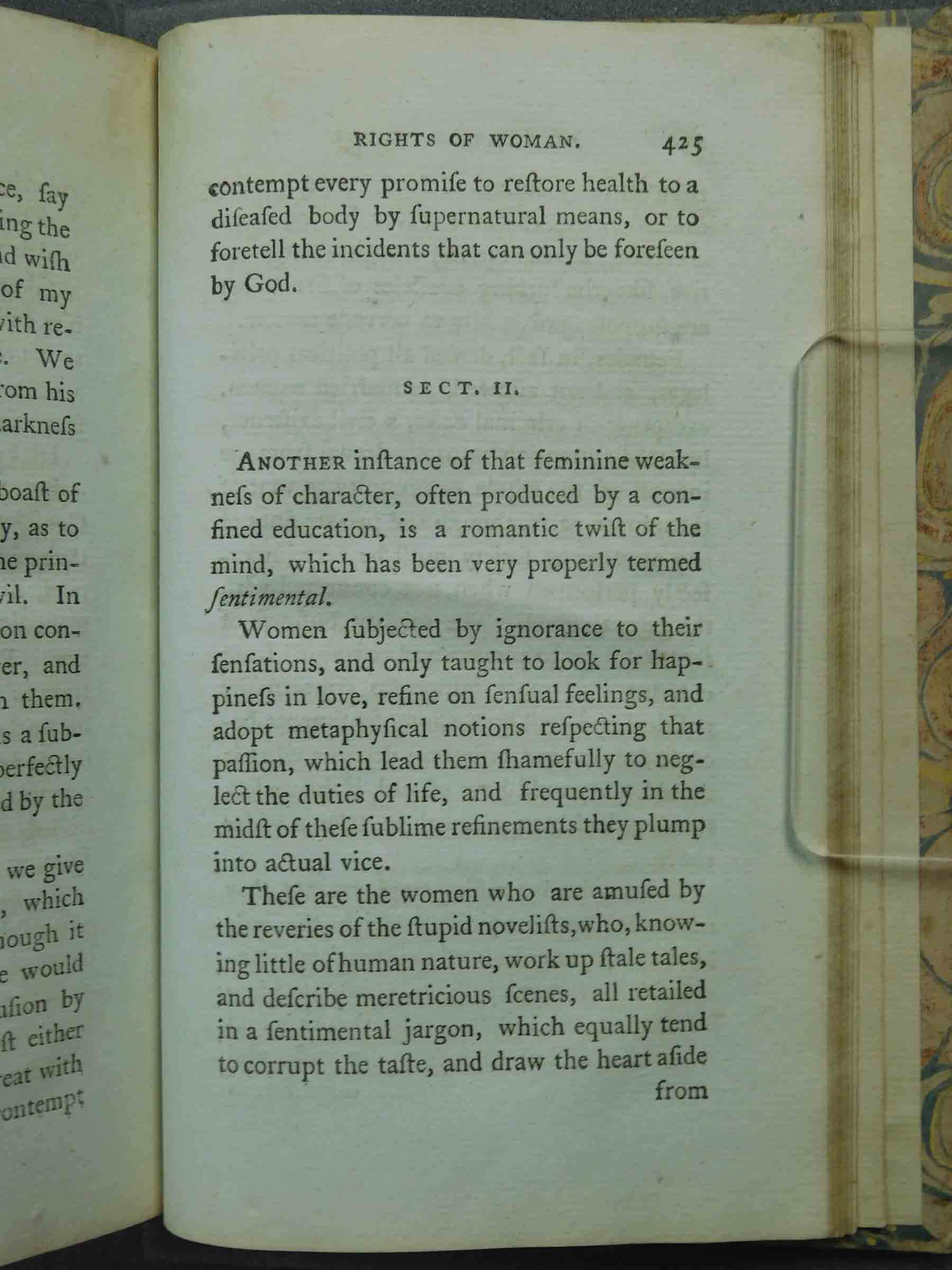

425 SECT. IIAnother instance of that feminine weakness of character, often produced by a confined education, is a romantic twist of the mind, which has been very properly termed sentimentalsentimental.

Women subjected by ignorance to their sensations, and only taught to look for happiness in love, refine on sensual feelings, and adopt metaphysical notions respecting that passion, which lead them shamefully to neglect the duties of life, and frequently in the midst of these sublime refinements they plump into actual vice.

Theses are women who are amused by the reveries of the stupid novelistsnovelists, who, knowing little of human nature, work up stale tales, and describe meretricious scenes, all retailed in sentimental jargon, which equally tend to corrupt the taste and draw the heart aside 426 from its daily duties. I do not mention the understanding, because never having been exercised, its slumbering energies rest inactive, like the lurking particles of fire which are supposed universally to pervade matter.

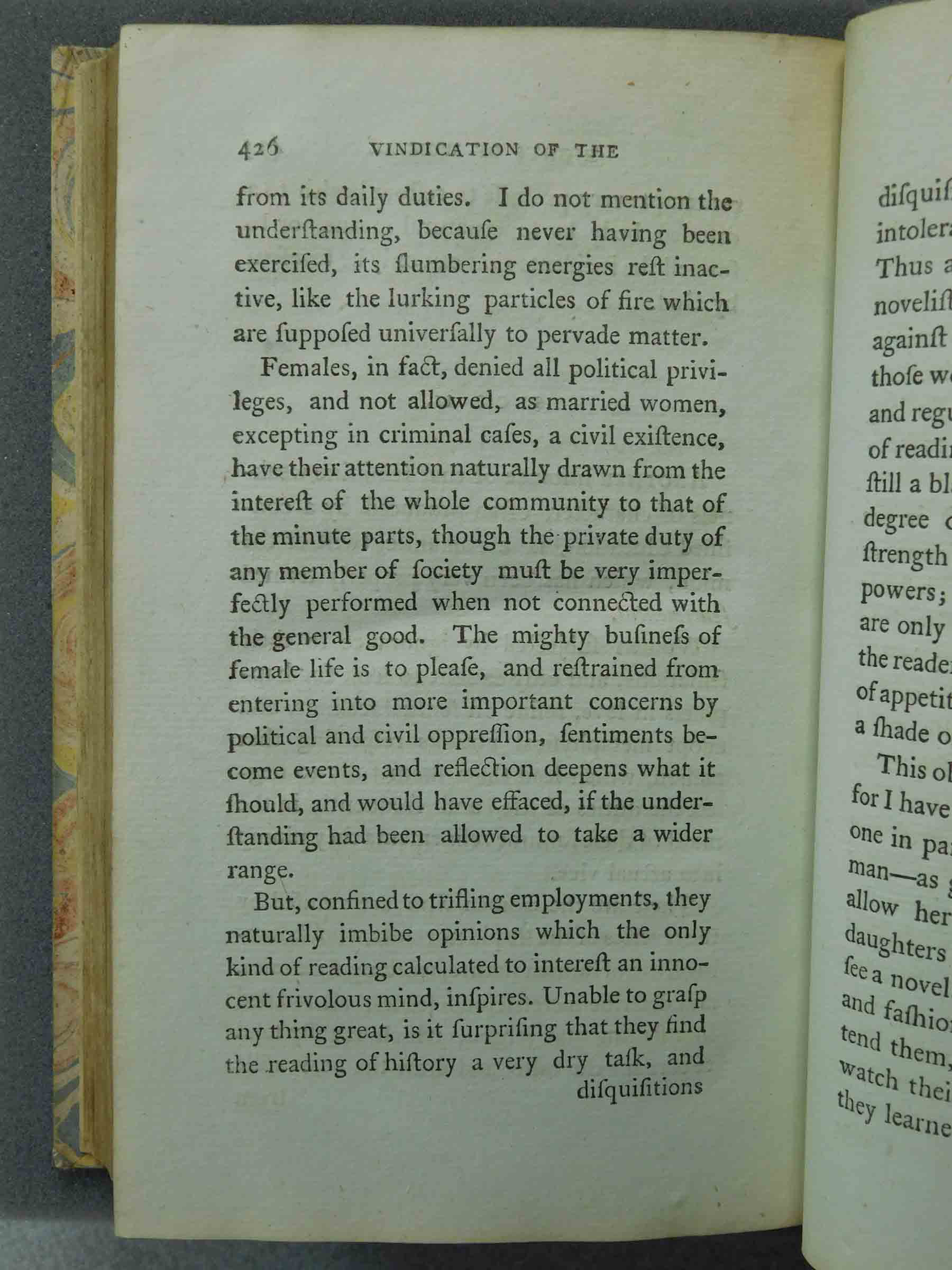

Females, in fact, denied all political privileges, and not allowed, as married women, excepting in criminal cases, a civil existence, have their attention naturally drawn from the interest of the whole community to that of the minute parts, though the private duty of any member of society must be very imperfectly performed when not connected with the general good. The mighty business of female life is to please, and restrained from entering into more important concerns by political and civil oppression, sentiments become events, and reflection deepens what it should, and would have effaced, if the understanding had been allowed to take a wider range.

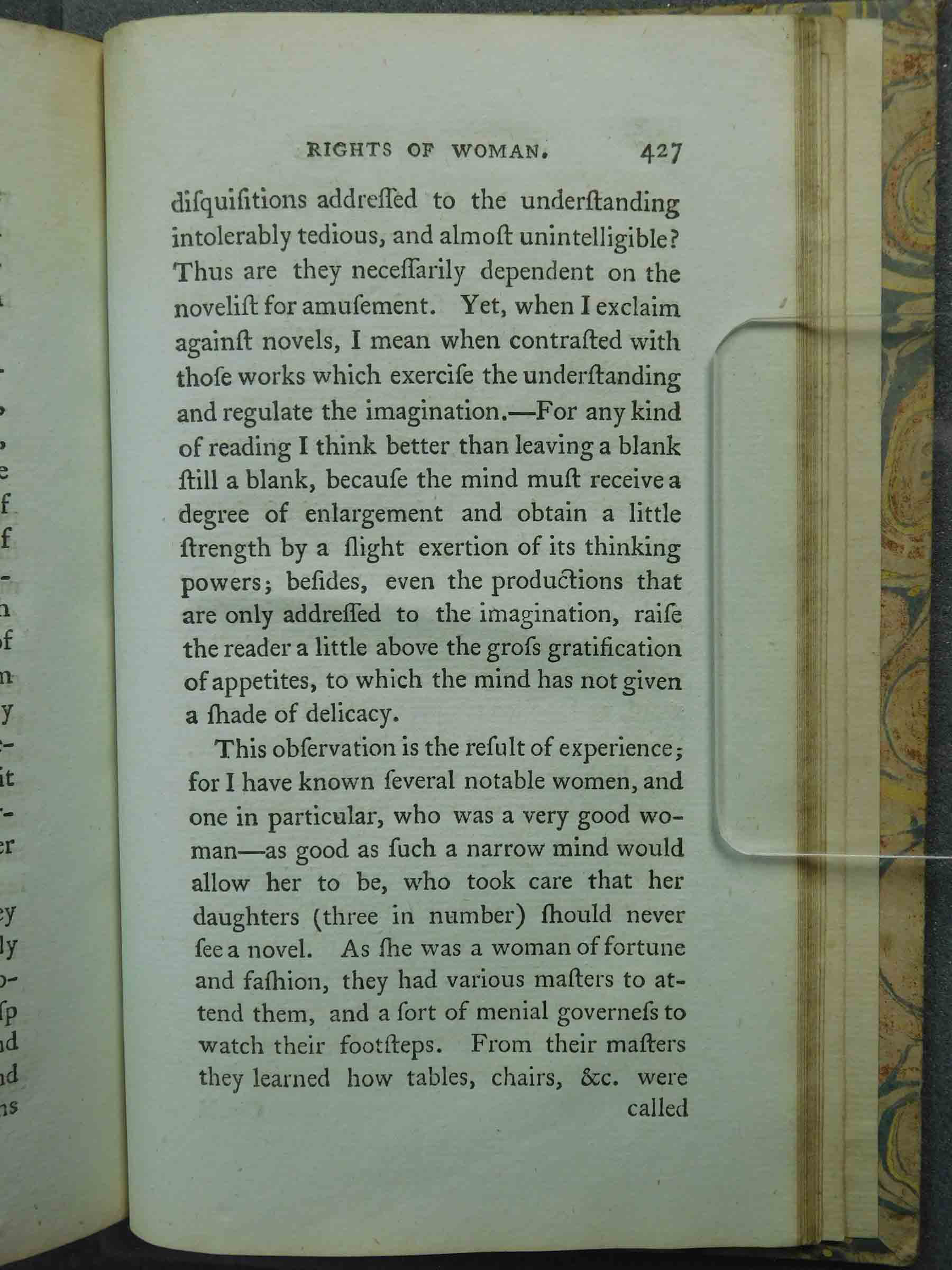

But, confined to trifling employmentstrifling_employments, they naturally imbibe opinions which the only kind of reading calculated to interest an innocent frivolous mind, inspires. Unable to grasp anything great, is it surprising that they find the reading of history a very dry talk, and 427 disquisitions addressed to the understanding intolerably tedious, and almost unintelligible? Thus are they necessarily dependent on the novelist for amusement. Yet, when I exclaim against novels, I mean when contrasted with those works which exercise the understanding and regulate the imagination.--For any kind of reading I think better than leaving a blank still a blank, because the mind must receive a degree of enlargement and obtain a little strength by a slight exertion of its thinking powers; besides, even the productions that are only addressed to the imagination, raise the reader a little above the gross gratification of appetites, to which the mind has not given shade of delicacy.

This observation is the result of experience; for I have known several notable women, and one in particular, who was a very good woman--as good as such a narrow mind would allow her to be, who took care that her daughters (three in number), should never see a novel. As she was a woman of fortune and fashion, they had various masters to attend them, and a sort of menial governessgoverness to watch their footsteps. From their masters they learned how tables, chairs, &c. were 428 called in French and Italian; but as the few books thrown in their way were far above their capacities, or devotional, they neither acquired ideas nor sentiments, and passed their time when not compelled to repeat words, in dressing, quarrelling with each other, or conversing with their maids by stealth, till they were brought into company as marriageable.

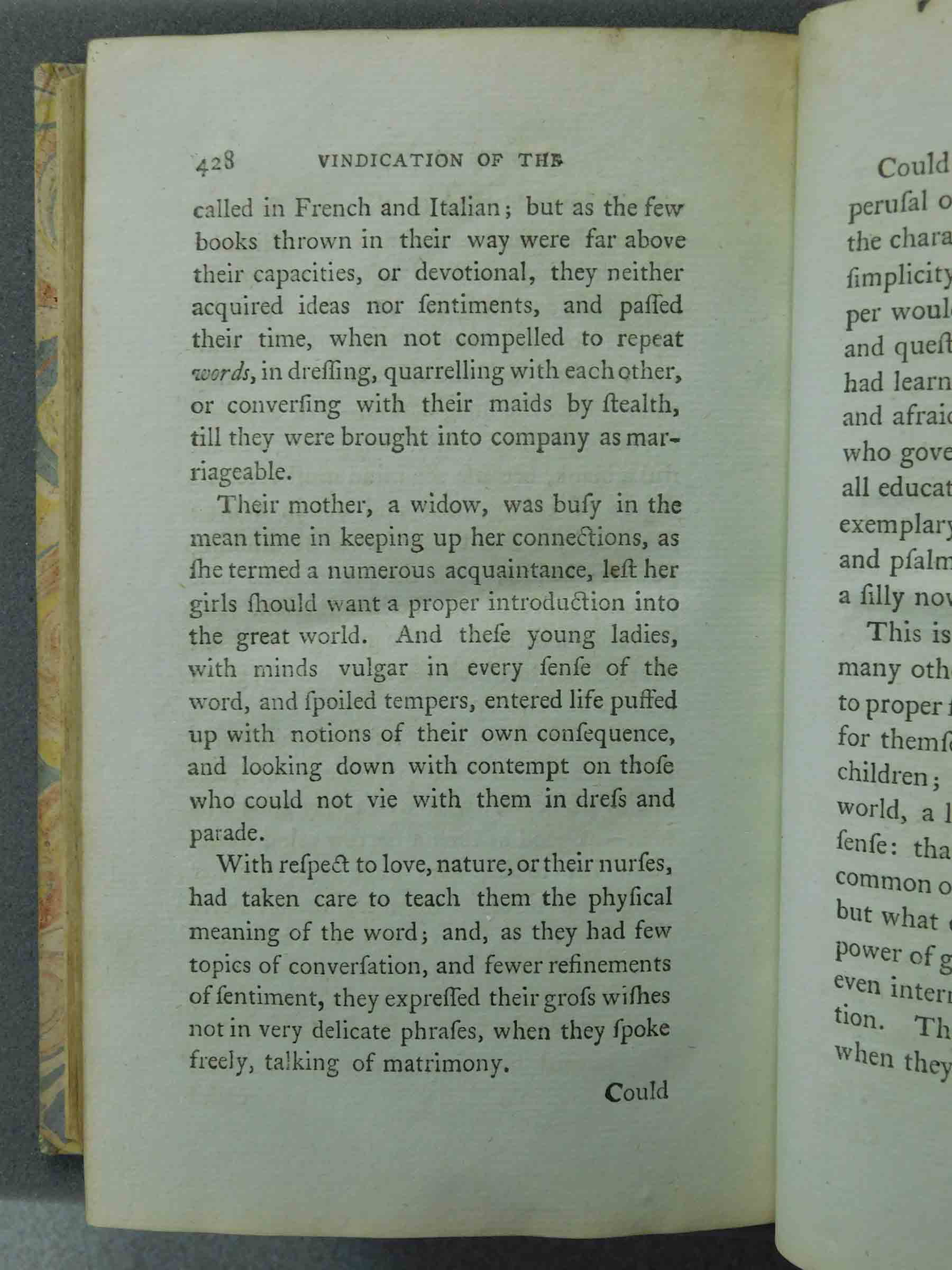

Their mother, a widow, was busy in the meantime keeping up her connections, as she termed a numerous acquaintance, lest her girls should want a proper introduction into the great world. And these young ladies with minds vulgar in every sense of the word, and spoiled tempers, entered life puffed up with notions of their own consequence, and looking down with contempt on those who could not vie with them in dress and parade.dress

With respect to love, nature, or their nurses had taken care to teach them the physical meaning of the word; and, as they had few topics of conversation, and fewer refinements on sentiment, they expressed their gross wishes not in very delicate phrases, when they spoke freely, talking of matrimony.

429Could these girls have been injured by the perusal of novels?novels I almost forgot a shade in the character of one of them; she affected a simplicity bordering on folly, and with a simper would utter the most immodest remarks and questions, the full meaning of which she had learned whilst secluded from the world, and afraid to speak in her mother’s presence, who governed with a high hand: they were all educated, as the prided herself, in most exemplary manner; and read their chapters and psalms before breakfast, never touching a silly novel.

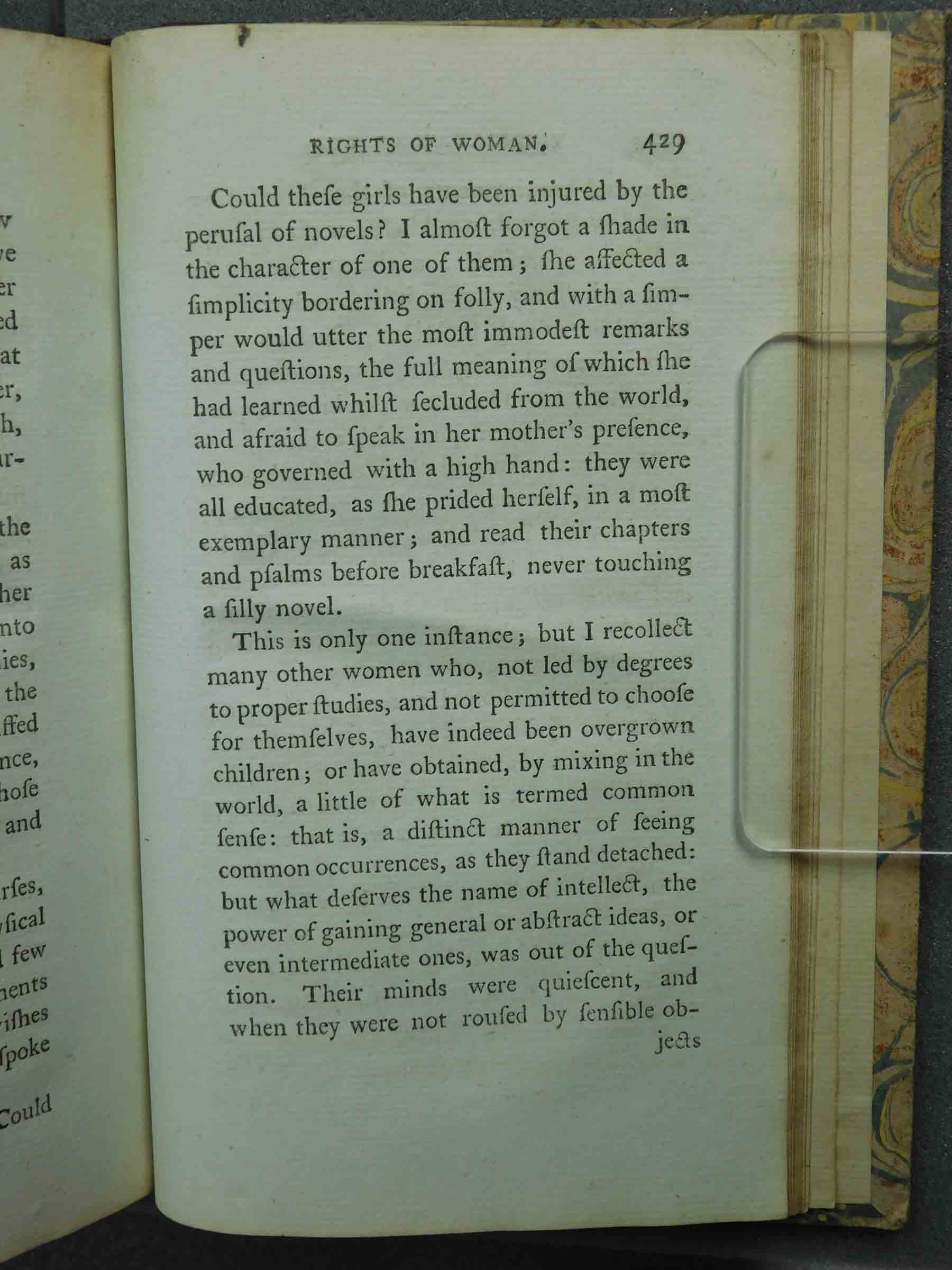

This is only one influence; but I recollect many other women who, not led by degrees to proper studies, and not permitted to choose for themselves, have indeed been overgrown children; or have obtained, by mixing in the world, a little of what is termed common sense; that is a distinct manner of feeling common occurrences, as they stand detached: but what deserves the name of intellect, the power of gaining general or abstract ideas, or even intermediate ones, was out of the question. Their minds were quiescent, and when they were not roused by sensible objects 430 [break after 'ob-']and employments of that kind, they were low-spirited, would cry, or go to sleep.

When, therefore, I advise my sex not to reach such flimsy works, it is to induce them to read something superior; for I coincide in opinion with sagacious man, who, having a daughter and niece under his care, pursued a very different plan with each.

The niece, who had considerable abilities, had, before she was left to his guardianship, been indulged in desultory reading. There she endeavoured to lead, and did lead to history and moral essays; but his daughter, whom a fond, weak mother had indulged, and who consequently was averse to everything like application, he allowed to read novels: and used to justify his conduct by saying, that if she ever attained a relish for reading them, he should have some foundation to work upon; and that erroneous opinions were better than none at all.

In fact the female mind has been so totally neglected, that knowledge was only to be acquired from this muddy source, till from reading novels some women of superior talents learned to despite them.

431The best method, I believe, that can be adopted to correct a fondness for novels is to ridicule them: not indiscriminately, for then it would have little effect; but, if a judicious person, with some turn for humour, would read several to a young girl, and point out both tones, and apt comparisons with pathetic incidents and heroic characters in history, how foolishly and ridiculously they captured human nature, just opinions might be substituted instead of romantic sentiments.

In one respect, however, the majority of both sexes resemble, and equally shew a want of taste and modesty. Ignorant women, forced to be chaste to preserve their reputation, allow their imagination to revel in the unnatural and meretricious scenes sketched by the novel writers of the day, slighting as insipid the sober dignity and matronly graces of historyhistory *auth2, whilst men carry the same vitiated taste into life, and fly for amusement to the wanton, from the unsophisticated charms 432 of virtue, and the grave respectability of sense.

Besides, the reading of novels makes women, and particularly ladies of fashion, very fond of using strong expressions and superlatives in conversation; and, though the dissipated artificial life which they lead prevents their cherishing and strong legitimate passion, the language of passion in affected tones slips for ever from their glib tongues, and every trifle produces those phosphoric bursts which only mimick in the dark the flame of passionphosphorus.

wollstonecraft Born in London on April 27, 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is considered

one of the principal figures in modern feminism. Her works reflected her unmarried

middle class experience, emphasizing gender injustice, the failure of the education

system for young women, and the position of women in unhappy marriages. Her best known

work, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), argues that to

attain virtue, women need access to systemic education. See this biographical essay on Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd. The portrait of

Wollstonecraft included here, painted by John Opie (1797), is housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London. - [MUstudstaff]

mahometanism

Born in London on April 27, 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is considered

one of the principal figures in modern feminism. Her works reflected her unmarried

middle class experience, emphasizing gender injustice, the failure of the education

system for young women, and the position of women in unhappy marriages. Her best known

work, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), argues that to

attain virtue, women need access to systemic education. See this biographical essay on Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd. The portrait of

Wollstonecraft included here, painted by John Opie (1797), is housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London. - [MUstudstaff]

mahometanism

Source: 1848 lithograph by James Rattray showing an Afgan women under purdahA term used by Westerners to refer to Muslims, in this context

Mahometanism is associated with the limited opportunities and oppressed status of women

in the eighteenth century. As discussed in The

Feminization Debate in Eighteenth-Century England (2004) by E. Clery,

women were trained to obey their father and husband. This confinement and

domesticization was frequently described as "Mahometan" due to the misguided belief

among the English that Islam sees women as not possessing souls. Social reformer and

leader of the Blue Stockings Society, Elizabeth Montagu lamented in a letter about the

effects of such "Mahometan" belief, which is used to justify women's domestic

confinement (Clery 136). The image included here, an 1848 lithograph by James Rattray, shows

Afgan women under purdah. Image via

Wikimedia Commons. - [BT]

education

Source: 1848 lithograph by James Rattray showing an Afgan women under purdahA term used by Westerners to refer to Muslims, in this context

Mahometanism is associated with the limited opportunities and oppressed status of women

in the eighteenth century. As discussed in The

Feminization Debate in Eighteenth-Century England (2004) by E. Clery,

women were trained to obey their father and husband. This confinement and

domesticization was frequently described as "Mahometan" due to the misguided belief

among the English that Islam sees women as not possessing souls. Social reformer and

leader of the Blue Stockings Society, Elizabeth Montagu lamented in a letter about the

effects of such "Mahometan" belief, which is used to justify women's domestic

confinement (Clery 136). The image included here, an 1848 lithograph by James Rattray, shows

Afgan women under purdah. Image via

Wikimedia Commons. - [BT]

education

Mary Wollstonecraft noted the absence of proficient education for

young women in the eighteenth century and decided to establish a school. Wollstonecraft,

along with her sister Eliza, and friend Fanny Blood, opened the school in 1784. The

school was established in Newington Green just outside of London. Although the school

closed from financial distress in 1785, Wollstonecraft drew from her experience as a

teacher and wrote Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with

Reflections on Female Conduct in the more important Duties of Life (1787). The

above picture shows a plaque dedicated to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Newington Green

Primary School near where the school was located in the 18th century. For more

information on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, read this biographical essay

written by Sylvana Tomaselli. To look through a copy of Wollstonecraft's Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with Reflections on Female

Conduct in the more important Duties of Life click here for an

online version of the book from the London School of Economics’ digital library. - [NB]

trifling_employments

Mary Wollstonecraft noted the absence of proficient education for

young women in the eighteenth century and decided to establish a school. Wollstonecraft,

along with her sister Eliza, and friend Fanny Blood, opened the school in 1784. The

school was established in Newington Green just outside of London. Although the school

closed from financial distress in 1785, Wollstonecraft drew from her experience as a

teacher and wrote Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with

Reflections on Female Conduct in the more important Duties of Life (1787). The

above picture shows a plaque dedicated to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Newington Green

Primary School near where the school was located in the 18th century. For more

information on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, read this biographical essay

written by Sylvana Tomaselli. To look through a copy of Wollstonecraft's Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with Reflections on Female

Conduct in the more important Duties of Life click here for an

online version of the book from the London School of Economics’ digital library. - [NB]

trifling_employments

By "trifling employments," Wollstonecraft refers to the kinds of

things elegant women did to employ their time such as needlepoint. Not allowed to

participate in the masculine public sphere, women instead spent their time in domestic

labor and activities. Many were mothers and homemakers. These activities were not

masculine and serious but feminine and trifling. Read more on women’s work in the

eighteenth century in this article by

Susan E. Jones, also the source of this annotation. The portrait above, via the Frick

Collection, is a conversation piece by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) showing the

genteel young ladies Waldegrave engaged in such domestic work. - [MM]

history This is likely a reference to

discussions about the hierarchy of genres during the eighteenth century. Dorothee Birke,

author of Writing the Reader: Configurations of Cultural Practice in English Novel

(2016), explains that historical and philosophical works were seen to have

higher value than novels and poetry. The reason behind such a hierarchical placement is

the perception of fictional reading to be connected with ignorance as people are fed

unrealistic words. Thus, historical and philosophical works which were often based on

truth and it reality, were insightful readings that were ranked higher than unrealistic

or exaggerated works (Birke 63). - [DN]

sandford_merton Likely a reference to a popular

children’s book written in the eighteenth century, Sandford and

Merton (1783), by Thomas Day, is about two boys who grow up differently based on

social status. According to

Stephen Bending and Stephen Bygrave, the book is an indictment of upper class

"effete" masculinity (23). Tommy Merton is spoiled by middle class privileges and needs

to be re-educated to become as fine a man as Sandford, whose lower-class status

challenged him to develop, physically and mentally, into an admirable young man (3-4).

Interested viewers can also read an abridged

version of Day’s children’s book, published in 1792, at the Internet Archive. - [SV]

novelistsWollstonecraft's question refers to an

ongoing discussion about the work of novel-reading on young girls' intellectual growth.

It was thought dangerous for women to read novels because society feared that they would

not, as Anna North writes in "When Novels Were Bad for You," be able to "differentiate between fiction and

life." - [KS]

bubbled

By "trifling employments," Wollstonecraft refers to the kinds of

things elegant women did to employ their time such as needlepoint. Not allowed to

participate in the masculine public sphere, women instead spent their time in domestic

labor and activities. Many were mothers and homemakers. These activities were not

masculine and serious but feminine and trifling. Read more on women’s work in the

eighteenth century in this article by

Susan E. Jones, also the source of this annotation. The portrait above, via the Frick

Collection, is a conversation piece by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) showing the

genteel young ladies Waldegrave engaged in such domestic work. - [MM]

history This is likely a reference to

discussions about the hierarchy of genres during the eighteenth century. Dorothee Birke,

author of Writing the Reader: Configurations of Cultural Practice in English Novel

(2016), explains that historical and philosophical works were seen to have

higher value than novels and poetry. The reason behind such a hierarchical placement is

the perception of fictional reading to be connected with ignorance as people are fed

unrealistic words. Thus, historical and philosophical works which were often based on

truth and it reality, were insightful readings that were ranked higher than unrealistic

or exaggerated works (Birke 63). - [DN]

sandford_merton Likely a reference to a popular

children’s book written in the eighteenth century, Sandford and

Merton (1783), by Thomas Day, is about two boys who grow up differently based on

social status. According to

Stephen Bending and Stephen Bygrave, the book is an indictment of upper class

"effete" masculinity (23). Tommy Merton is spoiled by middle class privileges and needs

to be re-educated to become as fine a man as Sandford, whose lower-class status

challenged him to develop, physically and mentally, into an admirable young man (3-4).

Interested viewers can also read an abridged

version of Day’s children’s book, published in 1792, at the Internet Archive. - [SV]

novelistsWollstonecraft's question refers to an

ongoing discussion about the work of novel-reading on young girls' intellectual growth.

It was thought dangerous for women to read novels because society feared that they would

not, as Anna North writes in "When Novels Were Bad for You," be able to "differentiate between fiction and

life." - [KS]

bubbled

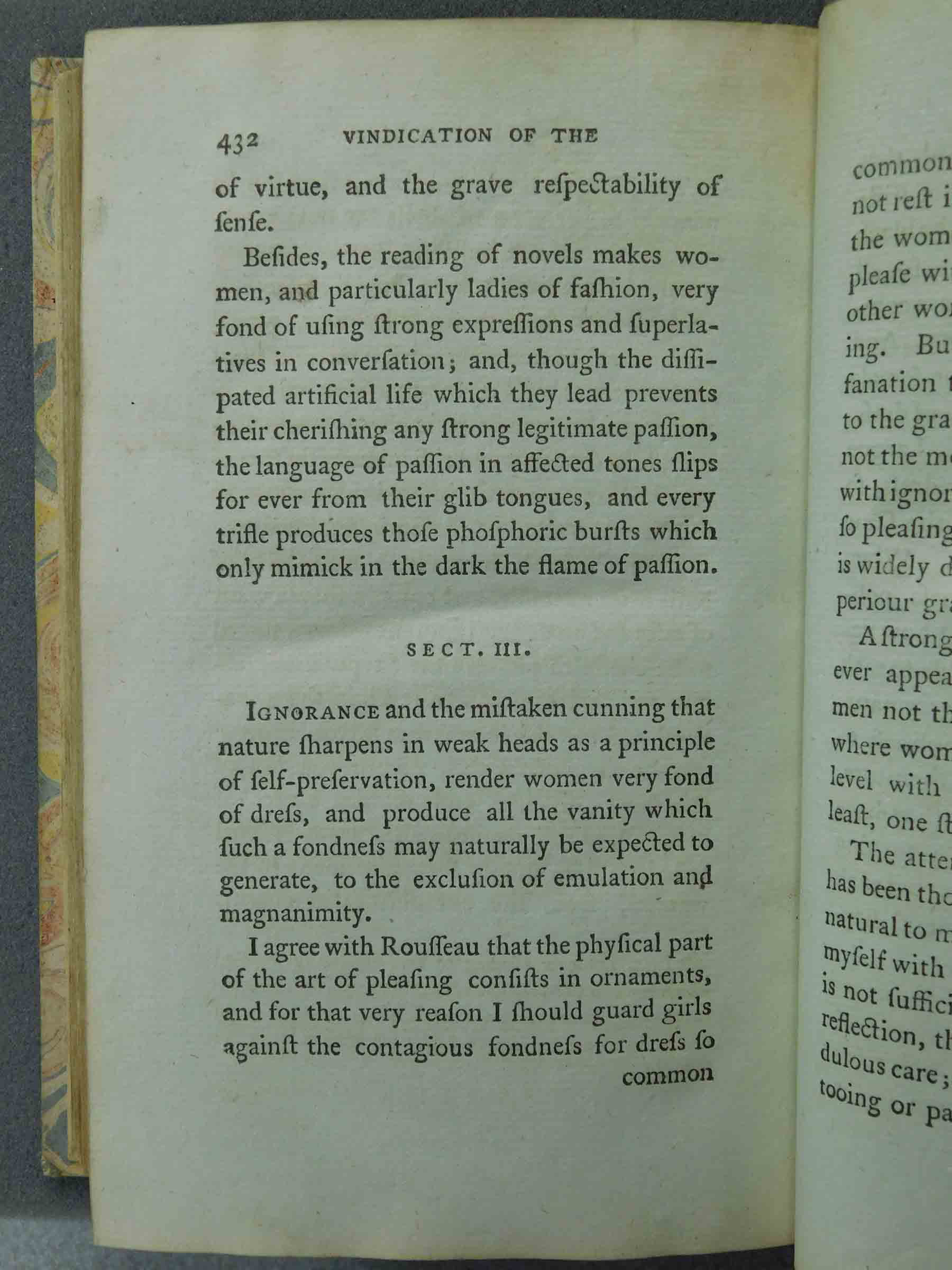

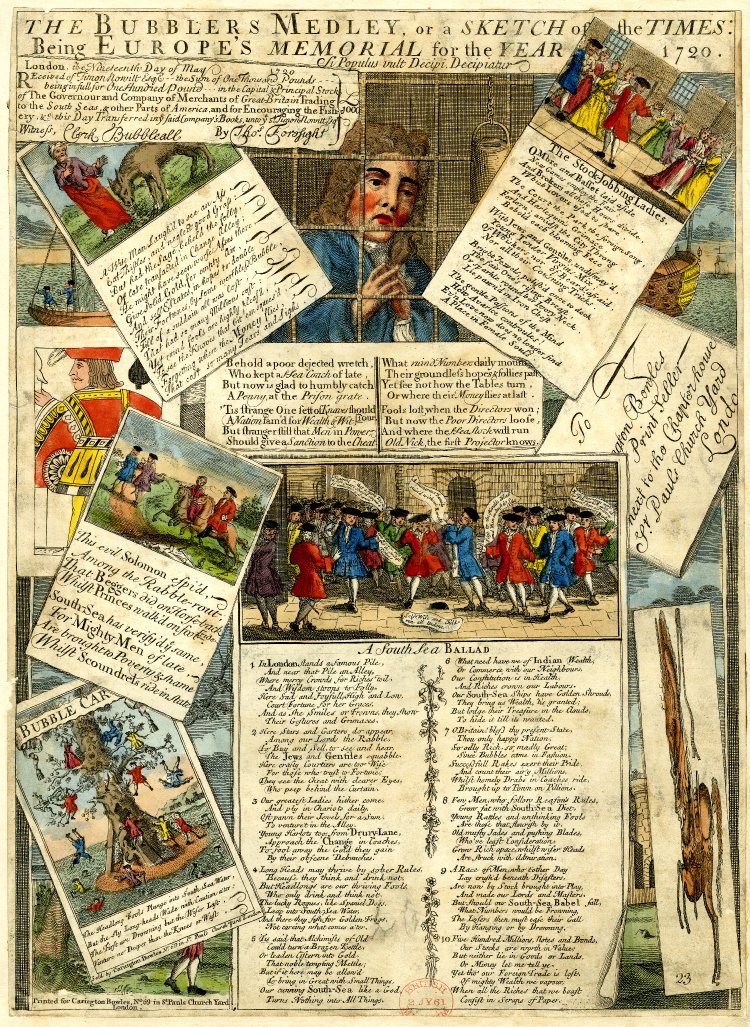

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the eighteenth-century

the word "bubbled" meant befooled, cheated, or deceived. Here, Wollstonecraft is saying

women’s understandings have been fooled by the popularization and distribution of

conduct books and their false depiction of women. "Bubbled" in this usage is also

derived from the devastating financial bubble in the eighteenth century, including the

South Sea Bubble of 1720. Many engravings and satirical prints of the time depict how

the people were deceived and cheated financially, most notably, The

Bubbler’s Medley, or a Sketch of the Times being Europe’s Memoriam for 1720.

The image included here is from the British Museum's online collection. To read more, visit Harvard Business School’s

online exhibit on the South Sea Bubble, and the source of this annotation. - [JMF]

conduct

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the eighteenth-century

the word "bubbled" meant befooled, cheated, or deceived. Here, Wollstonecraft is saying

women’s understandings have been fooled by the popularization and distribution of

conduct books and their false depiction of women. "Bubbled" in this usage is also

derived from the devastating financial bubble in the eighteenth century, including the

South Sea Bubble of 1720. Many engravings and satirical prints of the time depict how

the people were deceived and cheated financially, most notably, The

Bubbler’s Medley, or a Sketch of the Times being Europe’s Memoriam for 1720.

The image included here is from the British Museum's online collection. To read more, visit Harvard Business School’s

online exhibit on the South Sea Bubble, and the source of this annotation. - [JMF]

conduct

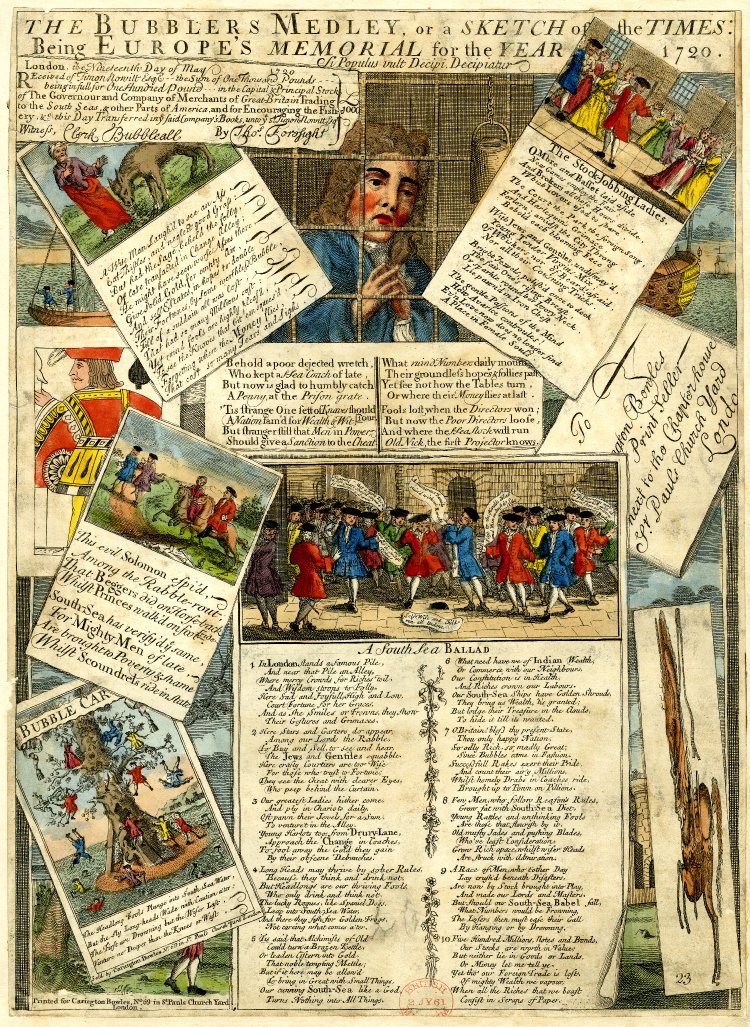

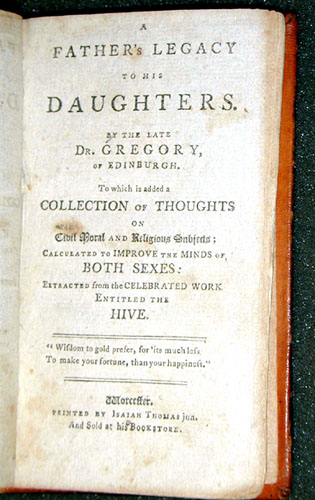

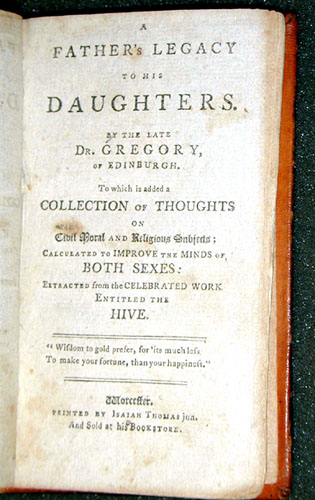

Source: The Title page of Gregory's conduct book

This is most likely a reference to Dr. John Gregory’s A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, a conduct book written prior

to Dr. Gregory’s wife’s passing in 1761 and addressed to his daughters about etiquette,

religion, conduct, and behaviors. Wollstonecraft references this book directly in many

of her arguments. The image of the book's title page (1795) is from the University of Delaware Special Collections Department is from the National Library of Scotland. View a 1793 edition of A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters at the Internet

Archive. - [BT]

johnson

Source: The Title page of Gregory's conduct book

This is most likely a reference to Dr. John Gregory’s A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, a conduct book written prior

to Dr. Gregory’s wife’s passing in 1761 and addressed to his daughters about etiquette,

religion, conduct, and behaviors. Wollstonecraft references this book directly in many

of her arguments. The image of the book's title page (1795) is from the University of Delaware Special Collections Department is from the National Library of Scotland. View a 1793 edition of A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters at the Internet

Archive. - [BT]

johnson

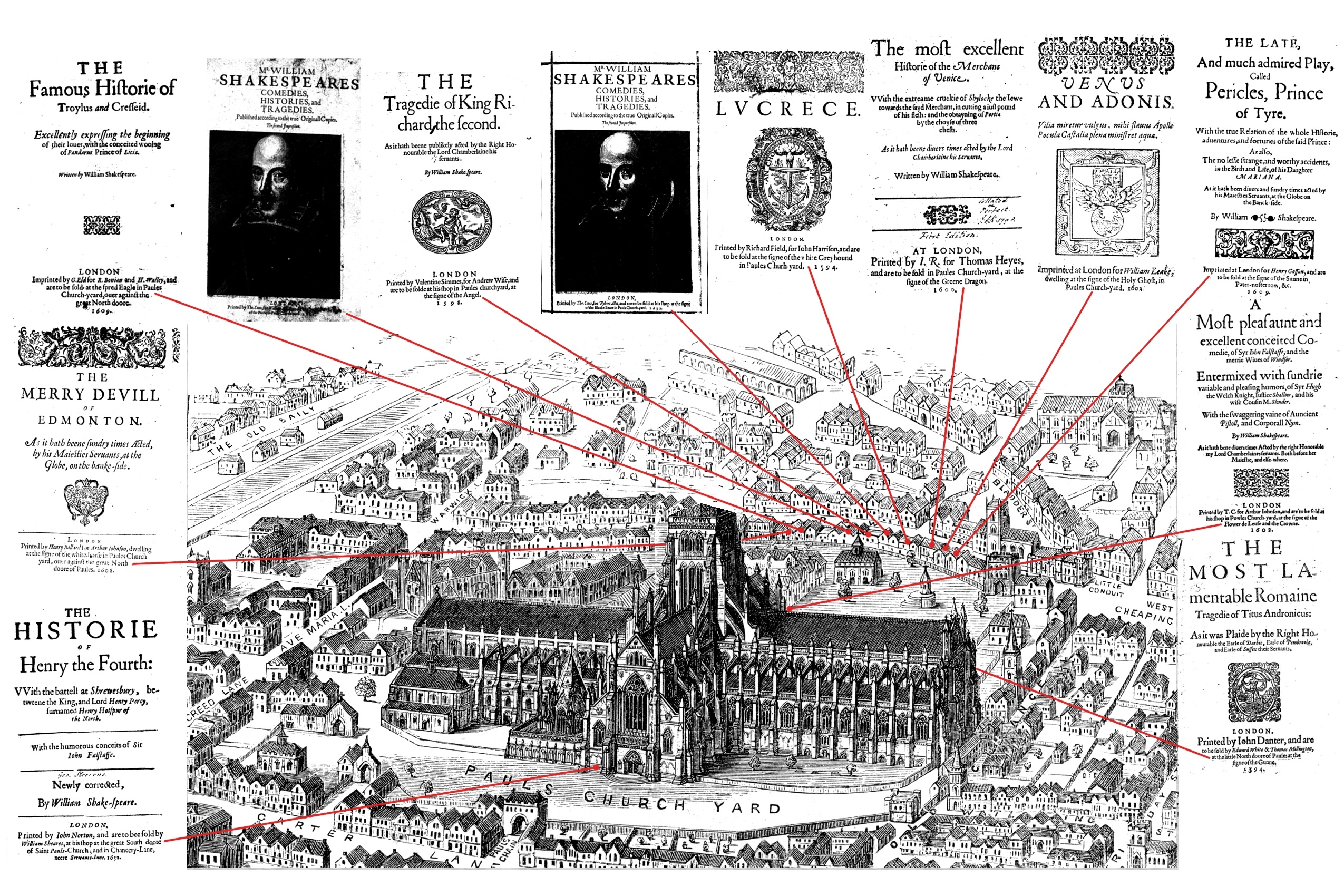

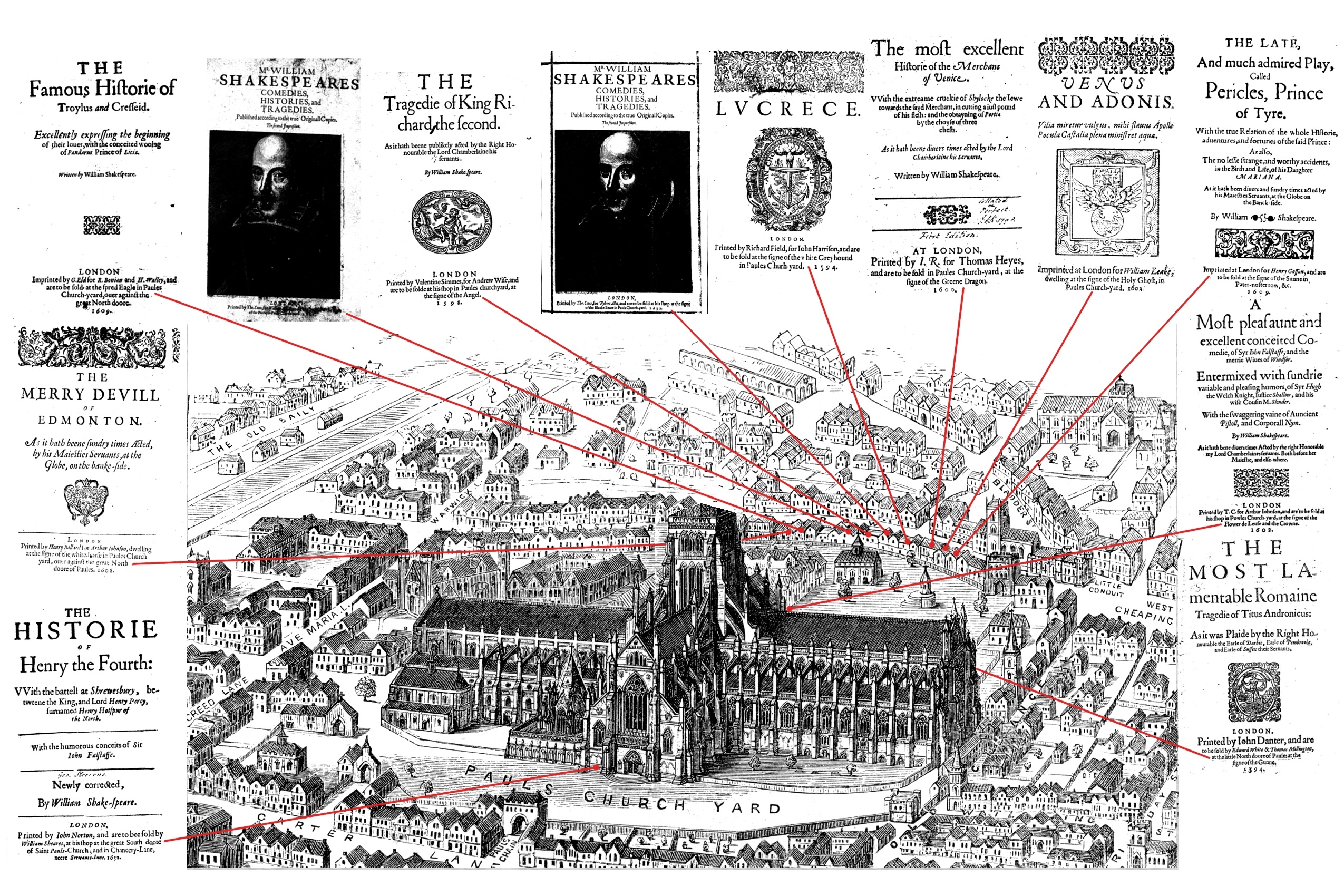

Throughout the eighteenth century, St. Paul’s Church Yard was the center of the

publishing trade. Wollstonecraft's Vindications was published by

Joseph Johnson, a liberal publisher with radical views, who published work by William

Godwin, Joseph Priestly, and William Blake. Wollstonecraft lived near St. Paul’s Church

Yard and spent many hours in this workshop as Joseph Johnson gave her writing and

translating jobs throughout the day. For more on the relationship between Mary

Wollstonecraft and Joseph Johnson, see this letter from Wollstonecraft to her publisher reprinted in The

American Reader. The image here, from a University of Louisville news

article on William Shakespeare's first folio, shows the locations of printers around St.

Paul's during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. - [TH]

elegance

Throughout the eighteenth century, St. Paul’s Church Yard was the center of the

publishing trade. Wollstonecraft's Vindications was published by

Joseph Johnson, a liberal publisher with radical views, who published work by William

Godwin, Joseph Priestly, and William Blake. Wollstonecraft lived near St. Paul’s Church

Yard and spent many hours in this workshop as Joseph Johnson gave her writing and

translating jobs throughout the day. For more on the relationship between Mary

Wollstonecraft and Joseph Johnson, see this letter from Wollstonecraft to her publisher reprinted in The

American Reader. The image here, from a University of Louisville news

article on William Shakespeare's first folio, shows the locations of printers around St.

Paul's during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. - [TH]

elegance

Elegance in the 18th century has a specific meaning when applied to

women. According to Robert

W. Jones, author of Gender and the Formation of Taste in

Eighteenth-Century Britain, feminine elegance is the combination of

docility and enticement of men. In the eighteenth century, elegance is feminized with

the goal that women should use it to please and seduce men through beauty and

refinement. Elegance of the eighteenth century is the area of the pleasing and amiable

actions from women to men, these beauty standards were important and a source of

intrigue for the culture (Jones 109). The image here, drawn from the National Gallery of

Art in Washington, DC, shows An Elegant Lady Playing a Cittern (1770), by Nathaniel

Dance-Holland. - [SM]

virtue Mary Wollstonecraft uses "virtue" with

its eighteenth-century sense of power. Men were often seen as virtuous because of their

physical strength, whereas women acquired virtue through sensibility and virginity.

Wollstonecraft argues that true virtue can only exist with knowledge and education.

Therefore, women must be properly educated or they would only be mimicking true virtue.

Views of Women in

Eighteenth Century Literature," published in the International

Journal of Communication Research by Adrian Brunello and Florina-Elena

Borsan reviews the way that understandings of womanhood shifted in the period, resulting

in the need for an exterior display of virtue, rather than true virtue (325-326). clicking here will direct you to the UK National Gallery of Art, showing An Allegory of Virtue and Riches, painted in 1667 by Godfried

Schalcken.

- [RB]

schools

Elegance in the 18th century has a specific meaning when applied to

women. According to Robert

W. Jones, author of Gender and the Formation of Taste in

Eighteenth-Century Britain, feminine elegance is the combination of

docility and enticement of men. In the eighteenth century, elegance is feminized with

the goal that women should use it to please and seduce men through beauty and

refinement. Elegance of the eighteenth century is the area of the pleasing and amiable

actions from women to men, these beauty standards were important and a source of

intrigue for the culture (Jones 109). The image here, drawn from the National Gallery of

Art in Washington, DC, shows An Elegant Lady Playing a Cittern (1770), by Nathaniel

Dance-Holland. - [SM]

virtue Mary Wollstonecraft uses "virtue" with

its eighteenth-century sense of power. Men were often seen as virtuous because of their

physical strength, whereas women acquired virtue through sensibility and virginity.

Wollstonecraft argues that true virtue can only exist with knowledge and education.

Therefore, women must be properly educated or they would only be mimicking true virtue.

Views of Women in

Eighteenth Century Literature," published in the International

Journal of Communication Research by Adrian Brunello and Florina-Elena

Borsan reviews the way that understandings of womanhood shifted in the period, resulting

in the need for an exterior display of virtue, rather than true virtue (325-326). clicking here will direct you to the UK National Gallery of Art, showing An Allegory of Virtue and Riches, painted in 1667 by Godfried

Schalcken.

- [RB]

schools

The

most common schools available for lower working class families in eighteenth-century

were dame schools. An elderly, barely literate, woman would teach reading and sewing for

a small fee. Read more in English Heritage’s brochure on England’s School. The

image of children learning in a dame school, painted by Thomas Webster (1845), is housed

in the Tate Art Museum, London.

- [FB]

sentimental The sentimental novel is a genre which

rose into popularity in the eighteenth century. This genre is characterized by

excessively passionate characters, tearful scenes and dramatic, flowery dialogue. Mary

Wollstonecraft may be using the popularity of these novels among young women to explain

their apparent lack of rationality rather than claiming irrationality to be a naturally

female trait. Read more about the sentimental novel in

Encyclopedia Britannica.

- [ES]

novelsAs novels became more accessible they

became more popular. Some believed that excessive exposure to fiction novels would cause

readers to lose touch with reality and identify with characters to the point of

mimicking dangerous or immoral behavior. Read more about a popular novel that was blamed

for youthful suicides in this article by Frank Furedi from

History Today. - [ES]

ranks The different ranks of society in

England during the eighteenth century were not simply divided between the rich or poor.

According to the eighteenth-century writer Daniel Defoe, there were seven categories:

the great, the rich, the middle sort, the working trades, the country people, the poor,

and the miserable. The country still relied on agriculture and, although some still died

of hunger, there was usually enough food to go around. Trade was increasing and more men

and women acquired jobs in industry. However, wealth was unequally distributed, with

only 5% of the national income belonging to the general population. Read more in this

Encyclopedia Britannica entry for eighteenth-century

Britain, and the source of this annotation. - [MR]

seraglio

The

most common schools available for lower working class families in eighteenth-century

were dame schools. An elderly, barely literate, woman would teach reading and sewing for

a small fee. Read more in English Heritage’s brochure on England’s School. The

image of children learning in a dame school, painted by Thomas Webster (1845), is housed

in the Tate Art Museum, London.

- [FB]

sentimental The sentimental novel is a genre which

rose into popularity in the eighteenth century. This genre is characterized by

excessively passionate characters, tearful scenes and dramatic, flowery dialogue. Mary

Wollstonecraft may be using the popularity of these novels among young women to explain

their apparent lack of rationality rather than claiming irrationality to be a naturally

female trait. Read more about the sentimental novel in

Encyclopedia Britannica.

- [ES]

novelsAs novels became more accessible they

became more popular. Some believed that excessive exposure to fiction novels would cause

readers to lose touch with reality and identify with characters to the point of

mimicking dangerous or immoral behavior. Read more about a popular novel that was blamed

for youthful suicides in this article by Frank Furedi from

History Today. - [ES]

ranks The different ranks of society in

England during the eighteenth century were not simply divided between the rich or poor.

According to the eighteenth-century writer Daniel Defoe, there were seven categories:

the great, the rich, the middle sort, the working trades, the country people, the poor,

and the miserable. The country still relied on agriculture and, although some still died

of hunger, there was usually enough food to go around. Trade was increasing and more men

and women acquired jobs in industry. However, wealth was unequally distributed, with

only 5% of the national income belonging to the general population. Read more in this

Encyclopedia Britannica entry for eighteenth-century

Britain, and the source of this annotation. - [MR]

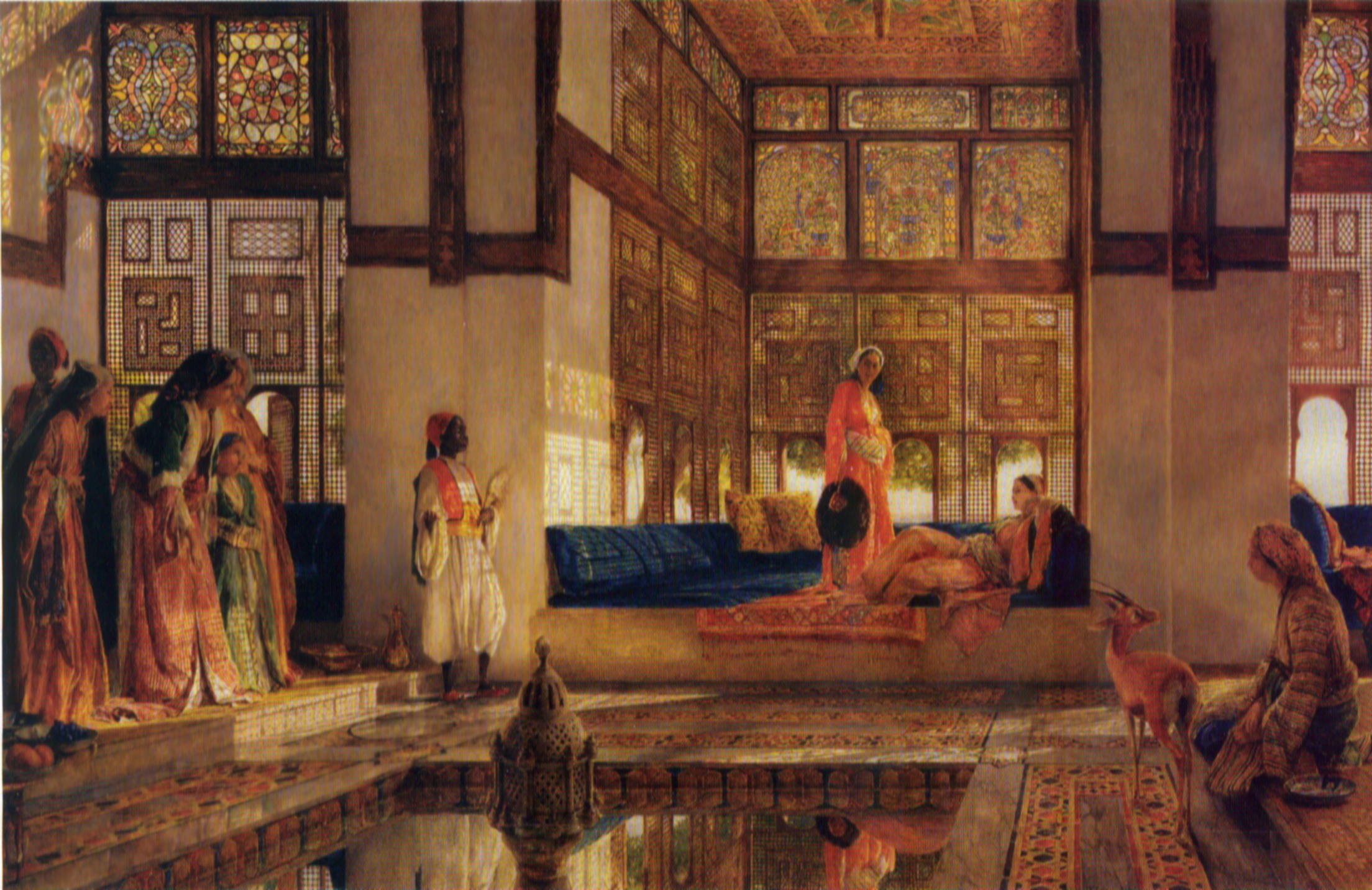

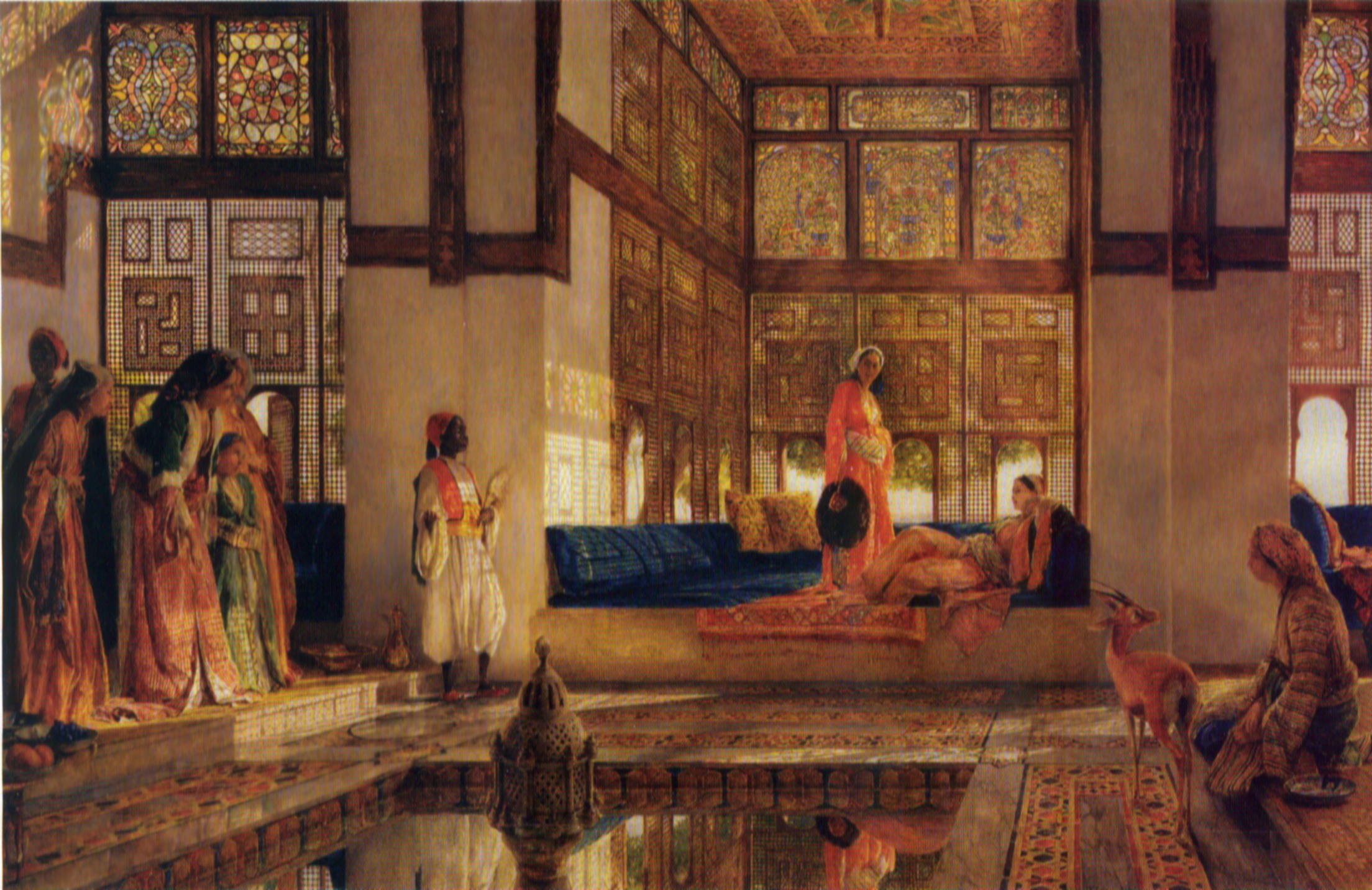

seraglio

Wollstonecraft’s argument in A Vindication of the

Rights of Woman is that women spend most of their lives acquiring knowledge to

be perfect wives instead of strengthening their minds and bodies to place a man. Because

the only way women can rise the world is through marriage, they are being groomed to

become lovers much like women in a Turkish seraglio, as Susan Gubar notes in "Feminist

Misogyny" (Gubar

151). Wollstonecraft is pointing out the lack of freedom for women. The image

included here illustrates the women’s quarter of a seraglio painted in 1873 by John

Frederick Lewis. This image is from Wikimedia Commons.

- [RDJ]

dress

Wollstonecraft’s argument in A Vindication of the

Rights of Woman is that women spend most of their lives acquiring knowledge to

be perfect wives instead of strengthening their minds and bodies to place a man. Because

the only way women can rise the world is through marriage, they are being groomed to

become lovers much like women in a Turkish seraglio, as Susan Gubar notes in "Feminist

Misogyny" (Gubar

151). Wollstonecraft is pointing out the lack of freedom for women. The image

included here illustrates the women’s quarter of a seraglio painted in 1873 by John

Frederick Lewis. This image is from Wikimedia Commons.

- [RDJ]

dress

In the eighteenth century, women were encouraged to focus on their

dress, meaning their overall attire, because as Dr. Gregory argues in A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, it was supposedly natural

to them (55). Women were dressed in hope of catching the attention of a man;

they would parade, or flaunt themselves to men, hoping to find a husband, which is the

only way for a woman to "rise in the world," as Wollstonecraft notes above (9).

Wollstonecraft didn’t want women to dress and flaunt themselves only for men’s

attention; she wanted women to focus on their own education. This portrait of Madame

Pompadour, located in the Alte Pinkothek Museum in Munich and via Wikimedia Commons, provides an example of

women’s attire in the 1700s in which Wollstonecraft was advising them not to do. Learn

more about eighteenth-century fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum. - [DF]

governess According to Katheryn Hughes, the governess was one of the most familiar figures in the

Romantic period and throughout the Victorian period. Governesses were women who earned

their living by teaching and caring for other women’s children. Most governesses lived

with their employers and were paid a small salary on top of their board and lodging. The

governess was seen as an outsider, not quite fitting in with the family she governed for

but not exactly fitting in as a servant either. - [AH]

manly

In the eighteenth century, women were encouraged to focus on their

dress, meaning their overall attire, because as Dr. Gregory argues in A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, it was supposedly natural

to them (55). Women were dressed in hope of catching the attention of a man;

they would parade, or flaunt themselves to men, hoping to find a husband, which is the

only way for a woman to "rise in the world," as Wollstonecraft notes above (9).

Wollstonecraft didn’t want women to dress and flaunt themselves only for men’s

attention; she wanted women to focus on their own education. This portrait of Madame

Pompadour, located in the Alte Pinkothek Museum in Munich and via Wikimedia Commons, provides an example of

women’s attire in the 1700s in which Wollstonecraft was advising them not to do. Learn

more about eighteenth-century fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum. - [DF]

governess According to Katheryn Hughes, the governess was one of the most familiar figures in the

Romantic period and throughout the Victorian period. Governesses were women who earned

their living by teaching and caring for other women’s children. Most governesses lived

with their employers and were paid a small salary on top of their board and lodging. The

governess was seen as an outsider, not quite fitting in with the family she governed for

but not exactly fitting in as a servant either. - [AH]

manly

"Manly virtues" in the eighteenth century refers to social

behavior that encourages men to be kind, loving, and courageous both in the home and in

the public domain. Since masculinity is, as Intertextual War: Edmund

Burke and the French Revolution in the Writings of Mary Wollstonecraft, Thomas Paine,

and James Mackintosh by Steven Blakemore, states, a "restrictive misnomer for

qualities or virtues that are human," Mary Wollstonecraft opposes men that inveigh

against masculine women because of its imitation of manly virtues (Blakemore 42). The portrait here, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews

by Thomas Gainsborough (1748), is housed in the National Gallery London. This painting,

via Wikimedia Commons, illustrates manliness in terms of gentility. - [RB]

phosphorus

"Manly virtues" in the eighteenth century refers to social

behavior that encourages men to be kind, loving, and courageous both in the home and in

the public domain. Since masculinity is, as Intertextual War: Edmund

Burke and the French Revolution in the Writings of Mary Wollstonecraft, Thomas Paine,

and James Mackintosh by Steven Blakemore, states, a "restrictive misnomer for

qualities or virtues that are human," Mary Wollstonecraft opposes men that inveigh

against masculine women because of its imitation of manly virtues (Blakemore 42). The portrait here, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews

by Thomas Gainsborough (1748), is housed in the National Gallery London. This painting,

via Wikimedia Commons, illustrates manliness in terms of gentility. - [RB]

phosphorus

Used by alchemists throughout the seventeenth century, phosphorous was

officially designated the thirteenth element by Antoine Lavosier in 1777. Quack

physicians incorporated the eerily-glowing phosphorous into their "cure all" medicines.

Here, Wollstonecraft may be referring to a long-standing association between the element

and its use in false medicines as well as its generation of artificial light. The image

included here, The Alchymist, In Search of the Philosopher’s Stone,

Discovers Phosphorus (1770) is by Joseph Wright of Derby, via Wikimedia Commons. Read more about the discovery of phosphorus on the personal blog Res Obscura. - [TG]

Used by alchemists throughout the seventeenth century, phosphorous was

officially designated the thirteenth element by Antoine Lavosier in 1777. Quack

physicians incorporated the eerily-glowing phosphorous into their "cure all" medicines.

Here, Wollstonecraft may be referring to a long-standing association between the element

and its use in false medicines as well as its generation of artificial light. The image

included here, The Alchymist, In Search of the Philosopher’s Stone,

Discovers Phosphorus (1770) is by Joseph Wright of Derby, via Wikimedia Commons. Read more about the discovery of phosphorus on the personal blog Res Obscura. - [TG]

Footnotes

Born in London on April 27, 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is considered

one of the principal figures in modern feminism. Her works reflected her unmarried

middle class experience, emphasizing gender injustice, the failure of the education

system for young women, and the position of women in unhappy marriages. Her best known

work, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), argues that to

attain virtue, women need access to systemic education. See this biographical essay on Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd. The portrait of

Wollstonecraft included here, painted by John Opie (1797), is housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Born in London on April 27, 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is considered

one of the principal figures in modern feminism. Her works reflected her unmarried

middle class experience, emphasizing gender injustice, the failure of the education

system for young women, and the position of women in unhappy marriages. Her best known

work, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), argues that to

attain virtue, women need access to systemic education. See this biographical essay on Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd. The portrait of

Wollstonecraft included here, painted by John Opie (1797), is housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.  Source: 1848 lithograph by James Rattray showing an Afgan women under purdahA term used by Westerners to refer to Muslims, in this context

Mahometanism is associated with the limited opportunities and oppressed status of women

in the eighteenth century. As discussed in The

Feminization Debate in Eighteenth-Century England (2004) by E. Clery,

women were trained to obey their father and husband. This confinement and

domesticization was frequently described as "Mahometan" due to the misguided belief

among the English that Islam sees women as not possessing souls. Social reformer and

leader of the Blue Stockings Society, Elizabeth Montagu lamented in a letter about the

effects of such "Mahometan" belief, which is used to justify women's domestic

confinement (Clery 136). The image included here, an 1848 lithograph by James Rattray, shows

Afgan women under purdah. Image via

Wikimedia Commons.

Source: 1848 lithograph by James Rattray showing an Afgan women under purdahA term used by Westerners to refer to Muslims, in this context

Mahometanism is associated with the limited opportunities and oppressed status of women

in the eighteenth century. As discussed in The

Feminization Debate in Eighteenth-Century England (2004) by E. Clery,

women were trained to obey their father and husband. This confinement and

domesticization was frequently described as "Mahometan" due to the misguided belief

among the English that Islam sees women as not possessing souls. Social reformer and

leader of the Blue Stockings Society, Elizabeth Montagu lamented in a letter about the

effects of such "Mahometan" belief, which is used to justify women's domestic

confinement (Clery 136). The image included here, an 1848 lithograph by James Rattray, shows

Afgan women under purdah. Image via

Wikimedia Commons. Mary Wollstonecraft noted the absence of proficient education for

young women in the eighteenth century and decided to establish a school. Wollstonecraft,

along with her sister Eliza, and friend Fanny Blood, opened the school in 1784. The

school was established in Newington Green just outside of London. Although the school

closed from financial distress in 1785, Wollstonecraft drew from her experience as a

teacher and wrote Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with

Reflections on Female Conduct in the more important Duties of Life (1787). The

above picture shows a plaque dedicated to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Newington Green

Primary School near where the school was located in the 18th century. For more

information on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, read this biographical essay

written by Sylvana Tomaselli. To look through a copy of Wollstonecraft's Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with Reflections on Female

Conduct in the more important Duties of Life click here for an

online version of the book from the London School of Economics’ digital library.

Mary Wollstonecraft noted the absence of proficient education for

young women in the eighteenth century and decided to establish a school. Wollstonecraft,

along with her sister Eliza, and friend Fanny Blood, opened the school in 1784. The

school was established in Newington Green just outside of London. Although the school

closed from financial distress in 1785, Wollstonecraft drew from her experience as a

teacher and wrote Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with

Reflections on Female Conduct in the more important Duties of Life (1787). The

above picture shows a plaque dedicated to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Newington Green

Primary School near where the school was located in the 18th century. For more

information on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, read this biographical essay

written by Sylvana Tomaselli. To look through a copy of Wollstonecraft's Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with Reflections on Female

Conduct in the more important Duties of Life click here for an

online version of the book from the London School of Economics’ digital library.  By "trifling employments," Wollstonecraft refers to the kinds of

things elegant women did to employ their time such as needlepoint. Not allowed to

participate in the masculine public sphere, women instead spent their time in domestic

labor and activities. Many were mothers and homemakers. These activities were not

masculine and serious but feminine and trifling. Read more on women’s work in the

eighteenth century in this article by

Susan E. Jones, also the source of this annotation. The portrait above, via the Frick

Collection, is a conversation piece by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) showing the

genteel young ladies Waldegrave engaged in such domestic work.

By "trifling employments," Wollstonecraft refers to the kinds of

things elegant women did to employ their time such as needlepoint. Not allowed to

participate in the masculine public sphere, women instead spent their time in domestic

labor and activities. Many were mothers and homemakers. These activities were not

masculine and serious but feminine and trifling. Read more on women’s work in the

eighteenth century in this article by

Susan E. Jones, also the source of this annotation. The portrait above, via the Frick

Collection, is a conversation piece by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) showing the

genteel young ladies Waldegrave engaged in such domestic work.  According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the eighteenth-century

the word "bubbled" meant befooled, cheated, or deceived. Here, Wollstonecraft is saying

women’s understandings have been fooled by the popularization and distribution of

conduct books and their false depiction of women. "Bubbled" in this usage is also

derived from the devastating financial bubble in the eighteenth century, including the

South Sea Bubble of 1720. Many engravings and satirical prints of the time depict how

the people were deceived and cheated financially, most notably, The

Bubbler’s Medley, or a Sketch of the Times being Europe’s Memoriam for 1720.

The image included here is from the British Museum's online collection. To read more, visit Harvard Business School’s

online exhibit on the South Sea Bubble, and the source of this annotation.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the eighteenth-century

the word "bubbled" meant befooled, cheated, or deceived. Here, Wollstonecraft is saying

women’s understandings have been fooled by the popularization and distribution of

conduct books and their false depiction of women. "Bubbled" in this usage is also

derived from the devastating financial bubble in the eighteenth century, including the

South Sea Bubble of 1720. Many engravings and satirical prints of the time depict how

the people were deceived and cheated financially, most notably, The

Bubbler’s Medley, or a Sketch of the Times being Europe’s Memoriam for 1720.

The image included here is from the British Museum's online collection. To read more, visit Harvard Business School’s

online exhibit on the South Sea Bubble, and the source of this annotation.  Source: The Title page of Gregory's conduct book

This is most likely a reference to Dr. John Gregory’s A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, a conduct book written prior

to Dr. Gregory’s wife’s passing in 1761 and addressed to his daughters about etiquette,

religion, conduct, and behaviors. Wollstonecraft references this book directly in many

of her arguments. The image of the book's title page (1795) is from the University of Delaware Special Collections Department is from the National Library of Scotland. View a 1793 edition of A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters at the Internet

Archive.

Source: The Title page of Gregory's conduct book

This is most likely a reference to Dr. John Gregory’s A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, a conduct book written prior

to Dr. Gregory’s wife’s passing in 1761 and addressed to his daughters about etiquette,

religion, conduct, and behaviors. Wollstonecraft references this book directly in many

of her arguments. The image of the book's title page (1795) is from the University of Delaware Special Collections Department is from the National Library of Scotland. View a 1793 edition of A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters at the Internet

Archive. Throughout the eighteenth century, St. Paul’s Church Yard was the center of the

publishing trade. Wollstonecraft's Vindications was published by

Joseph Johnson, a liberal publisher with radical views, who published work by William

Godwin, Joseph Priestly, and William Blake. Wollstonecraft lived near St. Paul’s Church

Yard and spent many hours in this workshop as Joseph Johnson gave her writing and

translating jobs throughout the day. For more on the relationship between Mary

Wollstonecraft and Joseph Johnson, see this letter from Wollstonecraft to her publisher reprinted in The

American Reader. The image here, from a University of Louisville news

article on William Shakespeare's first folio, shows the locations of printers around St.

Paul's during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

Throughout the eighteenth century, St. Paul’s Church Yard was the center of the

publishing trade. Wollstonecraft's Vindications was published by

Joseph Johnson, a liberal publisher with radical views, who published work by William

Godwin, Joseph Priestly, and William Blake. Wollstonecraft lived near St. Paul’s Church

Yard and spent many hours in this workshop as Joseph Johnson gave her writing and

translating jobs throughout the day. For more on the relationship between Mary

Wollstonecraft and Joseph Johnson, see this letter from Wollstonecraft to her publisher reprinted in The

American Reader. The image here, from a University of Louisville news

article on William Shakespeare's first folio, shows the locations of printers around St.

Paul's during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.  Elegance in the 18th century has a specific meaning when applied to

women. According to Robert

W. Jones, author of Gender and the Formation of Taste in

Eighteenth-Century Britain, feminine elegance is the combination of

docility and enticement of men. In the eighteenth century, elegance is feminized with

the goal that women should use it to please and seduce men through beauty and

refinement. Elegance of the eighteenth century is the area of the pleasing and amiable

actions from women to men, these beauty standards were important and a source of

intrigue for the culture (Jones 109). The image here, drawn from the National Gallery of

Art in Washington, DC, shows An Elegant Lady Playing a Cittern (1770), by Nathaniel

Dance-Holland.

Elegance in the 18th century has a specific meaning when applied to

women. According to Robert

W. Jones, author of Gender and the Formation of Taste in

Eighteenth-Century Britain, feminine elegance is the combination of

docility and enticement of men. In the eighteenth century, elegance is feminized with

the goal that women should use it to please and seduce men through beauty and

refinement. Elegance of the eighteenth century is the area of the pleasing and amiable

actions from women to men, these beauty standards were important and a source of

intrigue for the culture (Jones 109). The image here, drawn from the National Gallery of

Art in Washington, DC, shows An Elegant Lady Playing a Cittern (1770), by Nathaniel

Dance-Holland.  The

most common schools available for lower working class families in eighteenth-century

were dame schools. An elderly, barely literate, woman would teach reading and sewing for

a small fee. Read more in English Heritage’s brochure on England’s School. The

image of children learning in a dame school, painted by Thomas Webster (1845), is housed

in the Tate Art Museum, London.

The

most common schools available for lower working class families in eighteenth-century

were dame schools. An elderly, barely literate, woman would teach reading and sewing for

a small fee. Read more in English Heritage’s brochure on England’s School. The

image of children learning in a dame school, painted by Thomas Webster (1845), is housed

in the Tate Art Museum, London.

Wollstonecraft’s argument in A Vindication of the

Rights of Woman is that women spend most of their lives acquiring knowledge to

be perfect wives instead of strengthening their minds and bodies to place a man. Because

the only way women can rise the world is through marriage, they are being groomed to

become lovers much like women in a Turkish seraglio, as Susan Gubar notes in "Feminist

Misogyny" (Gubar

151). Wollstonecraft is pointing out the lack of freedom for women. The image

included here illustrates the women’s quarter of a seraglio painted in 1873 by John

Frederick Lewis. This image is from Wikimedia Commons.

Wollstonecraft’s argument in A Vindication of the

Rights of Woman is that women spend most of their lives acquiring knowledge to

be perfect wives instead of strengthening their minds and bodies to place a man. Because

the only way women can rise the world is through marriage, they are being groomed to

become lovers much like women in a Turkish seraglio, as Susan Gubar notes in "Feminist

Misogyny" (Gubar

151). Wollstonecraft is pointing out the lack of freedom for women. The image

included here illustrates the women’s quarter of a seraglio painted in 1873 by John

Frederick Lewis. This image is from Wikimedia Commons.

In the eighteenth century, women were encouraged to focus on their

dress, meaning their overall attire, because as Dr. Gregory argues in A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, it was supposedly natural

to them (55). Women were dressed in hope of catching the attention of a man;

they would parade, or flaunt themselves to men, hoping to find a husband, which is the

only way for a woman to "rise in the world," as Wollstonecraft notes above (9).

Wollstonecraft didn’t want women to dress and flaunt themselves only for men’s

attention; she wanted women to focus on their own education. This portrait of Madame

Pompadour, located in the Alte Pinkothek Museum in Munich and via Wikimedia Commons, provides an example of

women’s attire in the 1700s in which Wollstonecraft was advising them not to do. Learn

more about eighteenth-century fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In the eighteenth century, women were encouraged to focus on their

dress, meaning their overall attire, because as Dr. Gregory argues in A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, it was supposedly natural

to them (55). Women were dressed in hope of catching the attention of a man;

they would parade, or flaunt themselves to men, hoping to find a husband, which is the

only way for a woman to "rise in the world," as Wollstonecraft notes above (9).

Wollstonecraft didn’t want women to dress and flaunt themselves only for men’s

attention; she wanted women to focus on their own education. This portrait of Madame

Pompadour, located in the Alte Pinkothek Museum in Munich and via Wikimedia Commons, provides an example of

women’s attire in the 1700s in which Wollstonecraft was advising them not to do. Learn

more about eighteenth-century fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum. "Manly virtues" in the eighteenth century refers to social

behavior that encourages men to be kind, loving, and courageous both in the home and in

the public domain. Since masculinity is, as Intertextual War: Edmund

Burke and the French Revolution in the Writings of Mary Wollstonecraft, Thomas Paine,

and James Mackintosh by Steven Blakemore, states, a "restrictive misnomer for

qualities or virtues that are human," Mary Wollstonecraft opposes men that inveigh

against masculine women because of its imitation of manly virtues (Blakemore 42). The portrait here, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews

by Thomas Gainsborough (1748), is housed in the National Gallery London. This painting,

via Wikimedia Commons, illustrates manliness in terms of gentility.

"Manly virtues" in the eighteenth century refers to social

behavior that encourages men to be kind, loving, and courageous both in the home and in

the public domain. Since masculinity is, as Intertextual War: Edmund

Burke and the French Revolution in the Writings of Mary Wollstonecraft, Thomas Paine,

and James Mackintosh by Steven Blakemore, states, a "restrictive misnomer for

qualities or virtues that are human," Mary Wollstonecraft opposes men that inveigh

against masculine women because of its imitation of manly virtues (Blakemore 42). The portrait here, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews

by Thomas Gainsborough (1748), is housed in the National Gallery London. This painting,

via Wikimedia Commons, illustrates manliness in terms of gentility.  Used by alchemists throughout the seventeenth century, phosphorous was

officially designated the thirteenth element by Antoine Lavosier in 1777. Quack

physicians incorporated the eerily-glowing phosphorous into their "cure all" medicines.

Here, Wollstonecraft may be referring to a long-standing association between the element

and its use in false medicines as well as its generation of artificial light. The image

included here, The Alchymist, In Search of the Philosopher’s Stone,

Discovers Phosphorus (1770) is by Joseph Wright of Derby, via Wikimedia Commons. Read more about the discovery of phosphorus on the personal blog Res Obscura.

Used by alchemists throughout the seventeenth century, phosphorous was

officially designated the thirteenth element by Antoine Lavosier in 1777. Quack

physicians incorporated the eerily-glowing phosphorous into their "cure all" medicines.

Here, Wollstonecraft may be referring to a long-standing association between the element

and its use in false medicines as well as its generation of artificial light. The image

included here, The Alchymist, In Search of the Philosopher’s Stone,

Discovers Phosphorus (1770) is by Joseph Wright of Derby, via Wikimedia Commons. Read more about the discovery of phosphorus on the personal blog Res Obscura.

![Page [TP]](https://anthologyassetsdev.lib.virginia.edu/wollstonecraft-vindication-excerpted/pageImages/VIN-TP.jpg)

![Page 4 [break after pre-]](https://anthologyassetsdev.lib.virginia.edu/wollstonecraft-vindication-excerpted/pageImages/VIN-4.jpg)

![Page 6 [break after 'hu-']](https://anthologyassetsdev.lib.virginia.edu/wollstonecraft-vindication-excerpted/pageImages/VIN-6.jpg)

![Page 9 [break after 'establish-']](https://anthologyassetsdev.lib.virginia.edu/wollstonecraft-vindication-excerpted/pageImages/VIN-9.jpg)

![Page 11 [break after 'in-']](https://anthologyassetsdev.lib.virginia.edu/wollstonecraft-vindication-excerpted/pageImages/VIN-11.jpg)

![Page 430 [break after 'ob-']](https://anthologyassetsdev.lib.virginia.edu/wollstonecraft-vindication-excerpted/pageImages/VIN-430.jpg)