Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral

By

Phillis Wheatley

Transcription, correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Students and Staff of Marymount University, Students and Staff of The University of

Virginia

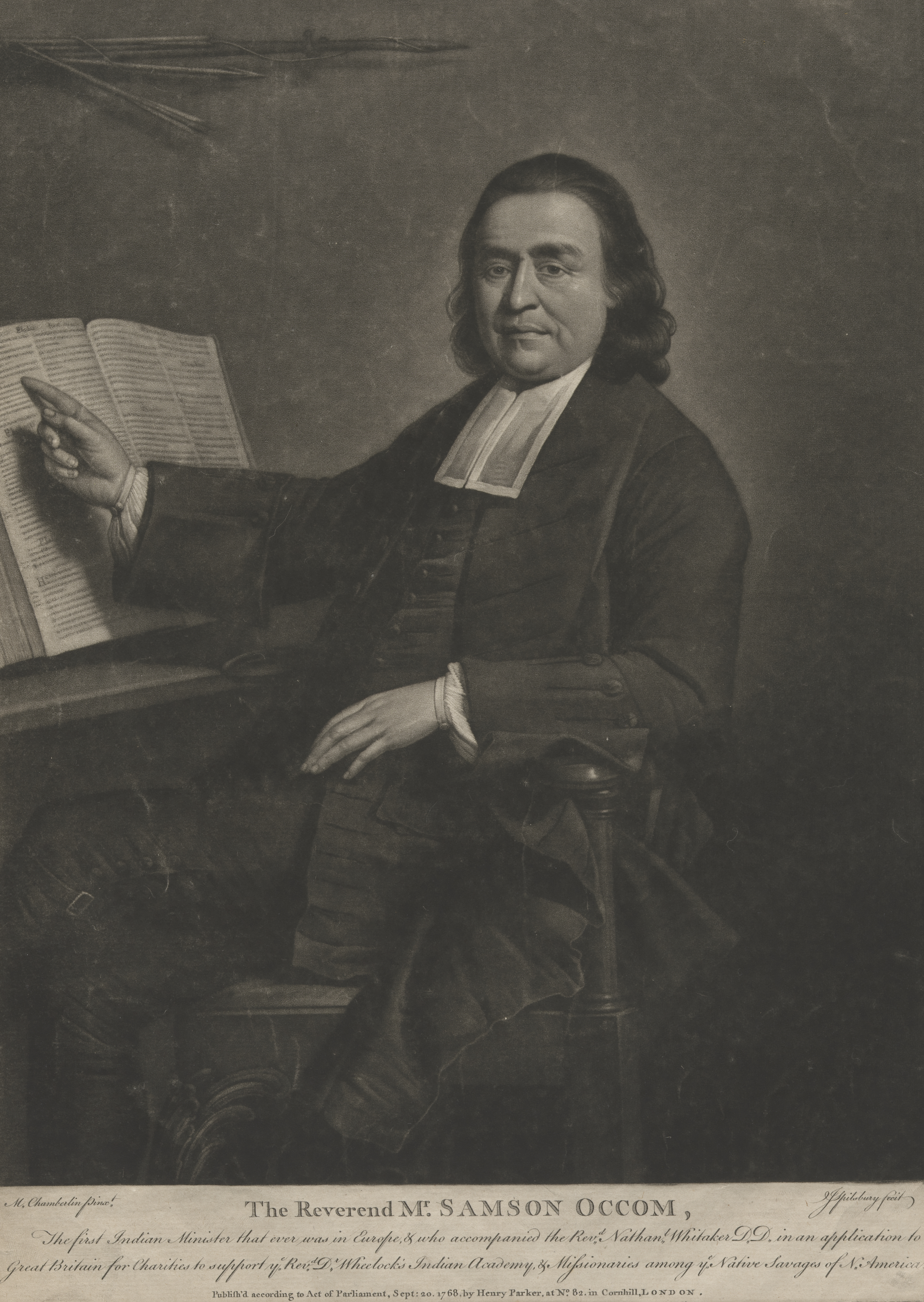

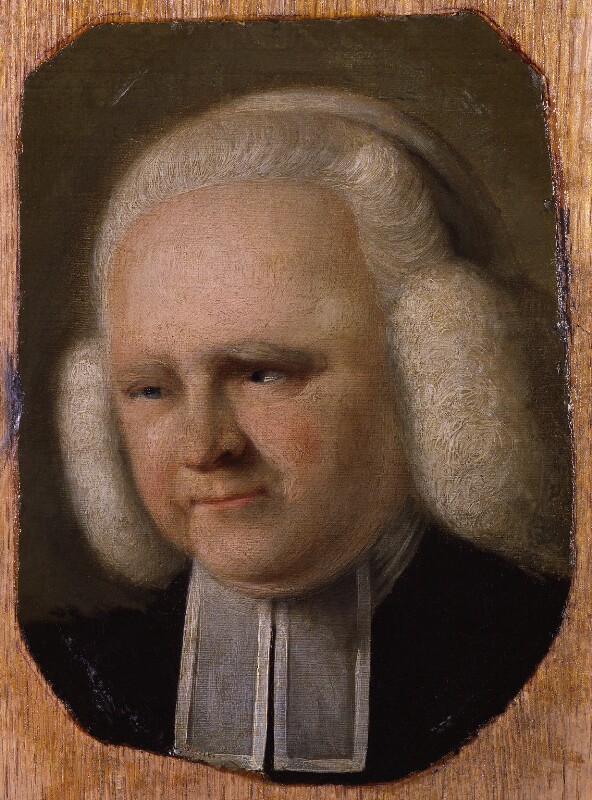

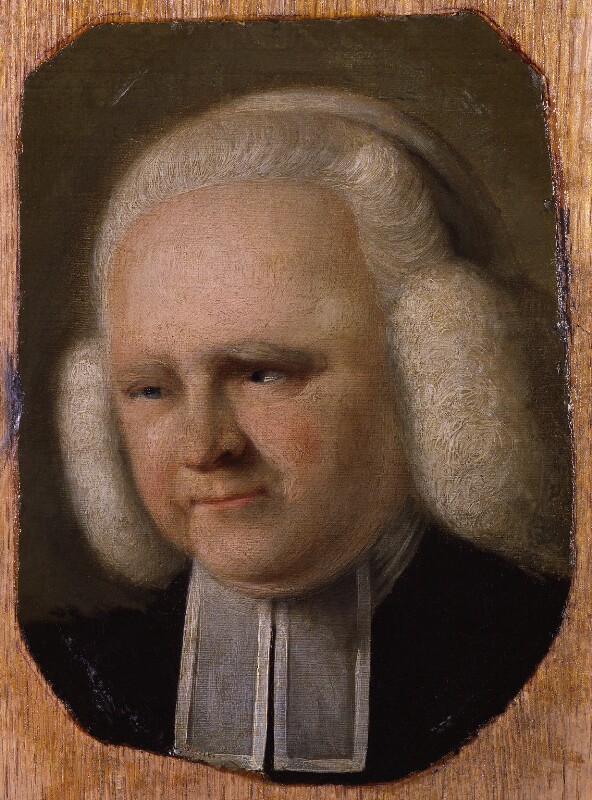

occomIn Wheatley's letter to Samson Occom, she affirms

his "Vindication of their [the enslaved] natural Rights." She concludes with an

ellipsis in which she implicitly criticizes the "strange Absurdity" of Christian

slavers. To read the letter in its entirety, visit American Literature I. Samson Occom

(1723-1792), a Native American member of the Mohegan Nation, was an author,

teacher, judge, and Presbyterian minister. The image here, via Wikimedia Commons,

is a mezzotint portrait of the Reverend Occom from 1768. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samson_Occom

- [MUStudStaff]maecenas

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samson_Occom

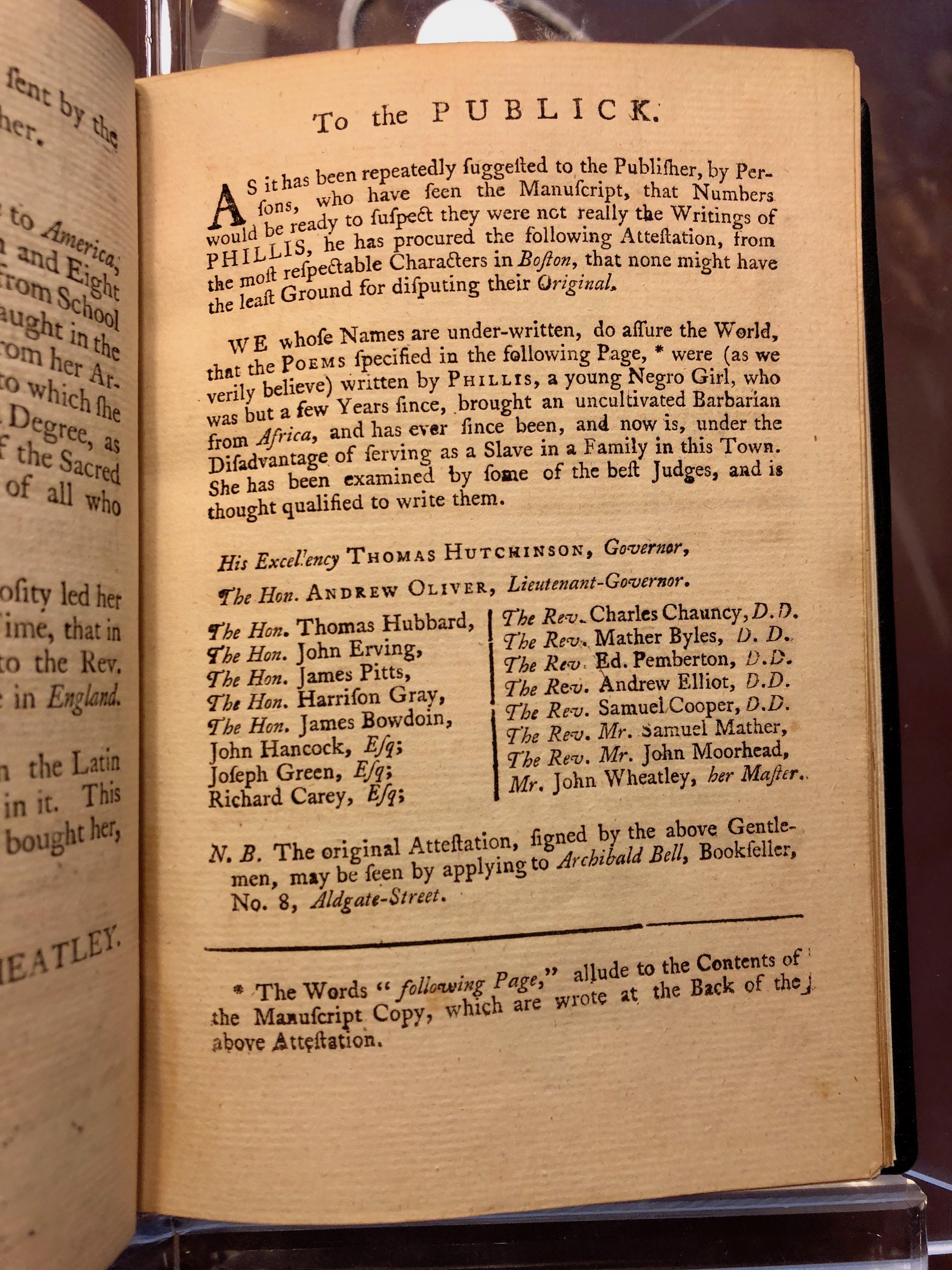

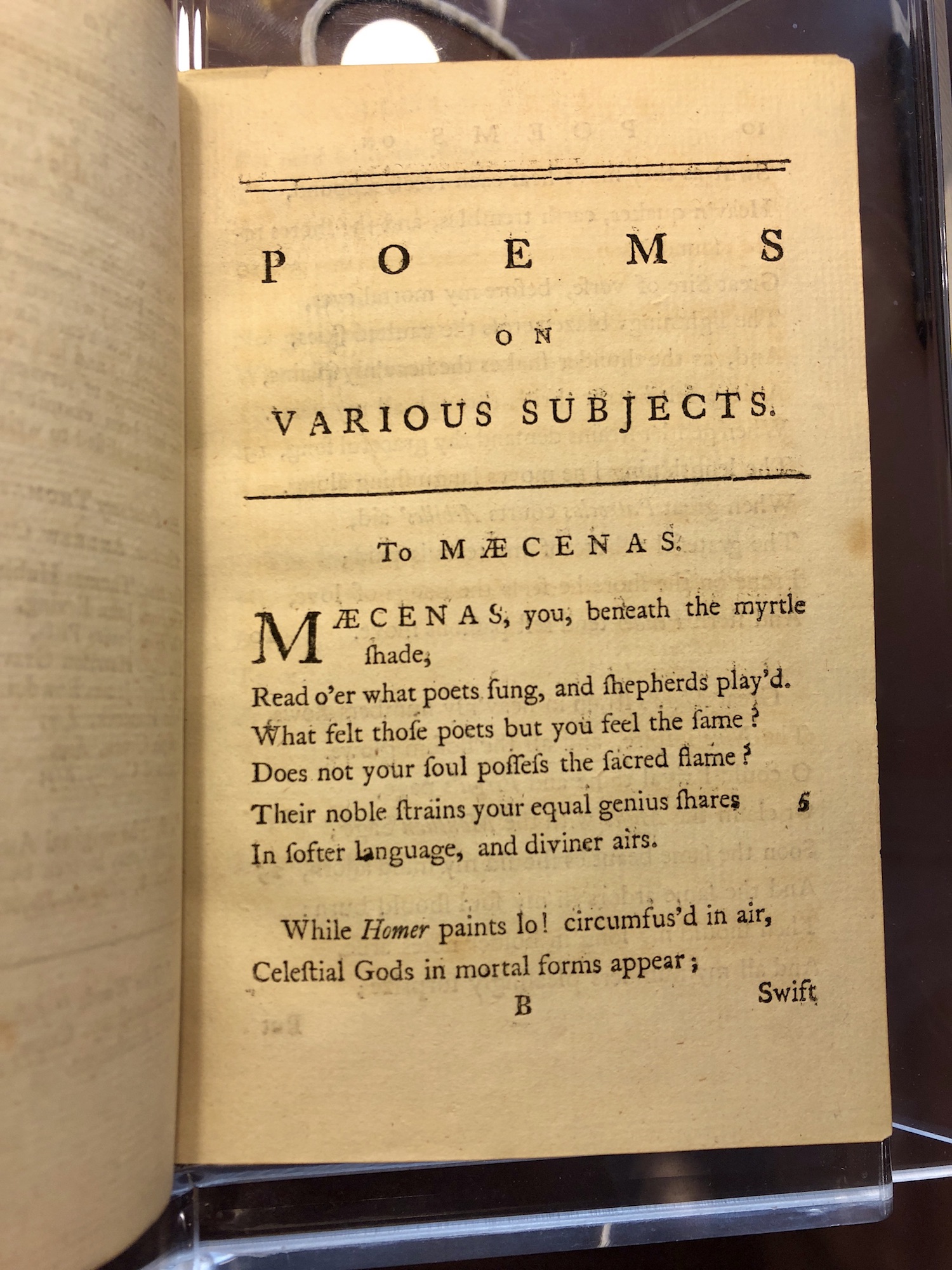

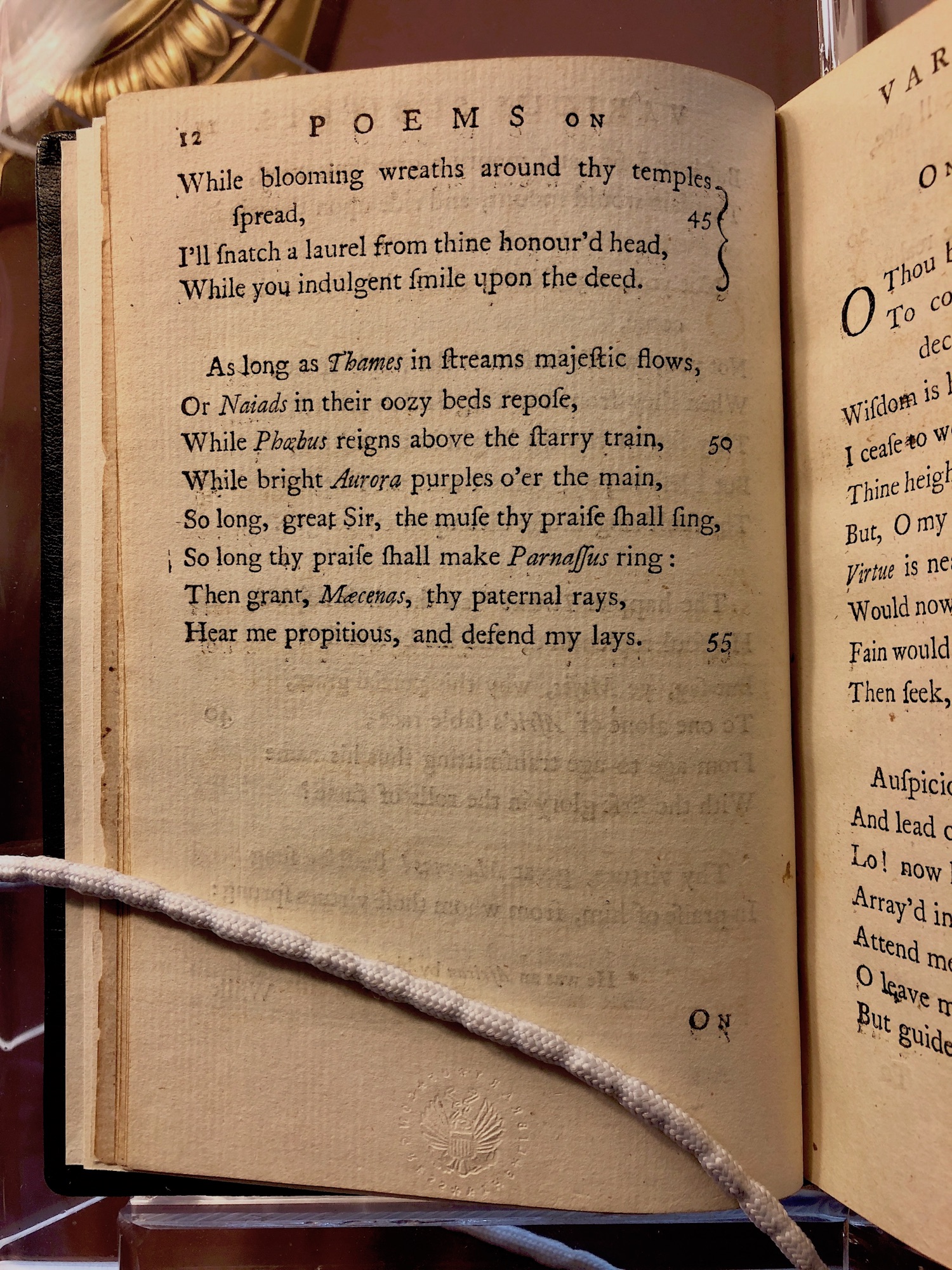

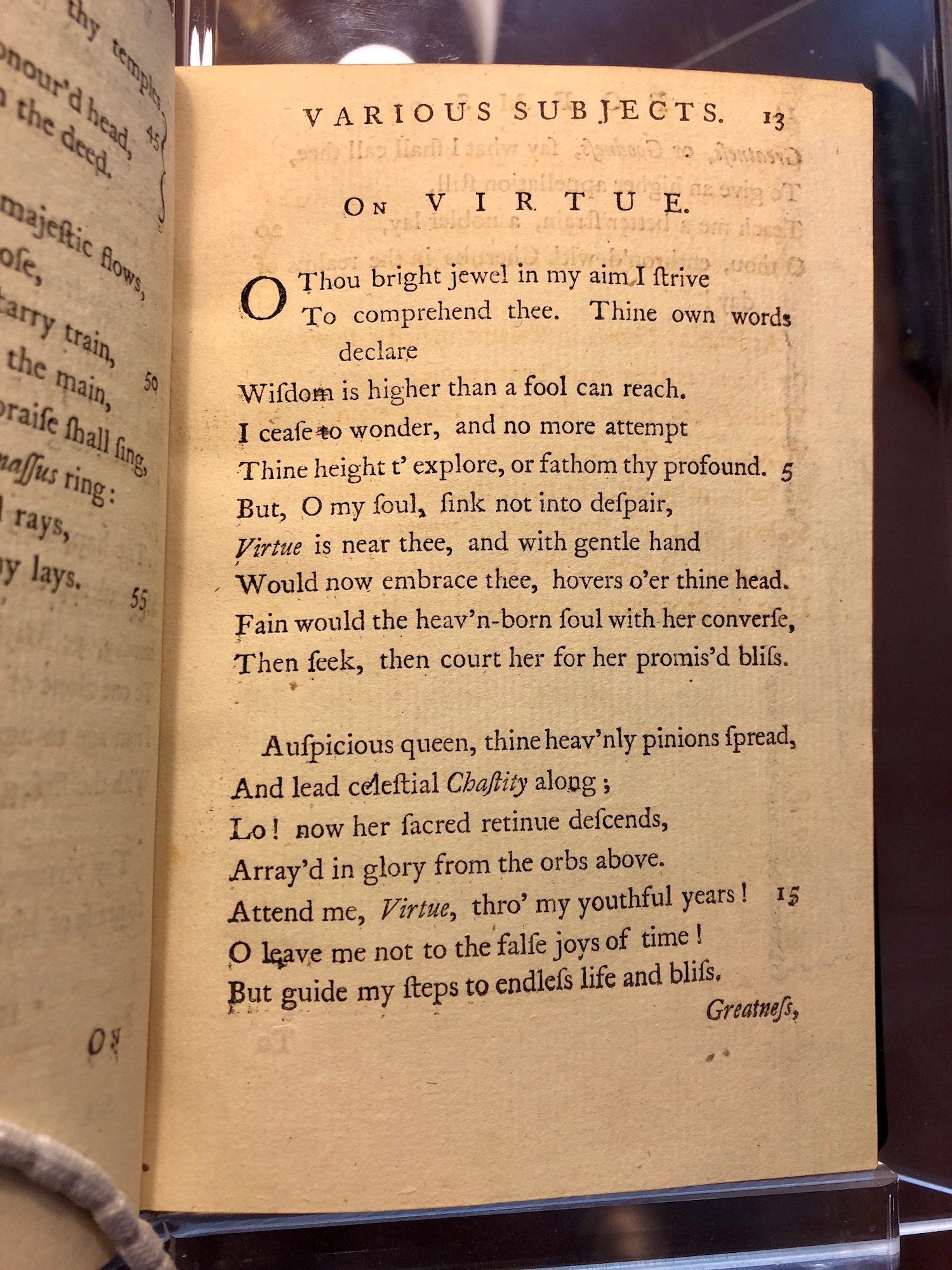

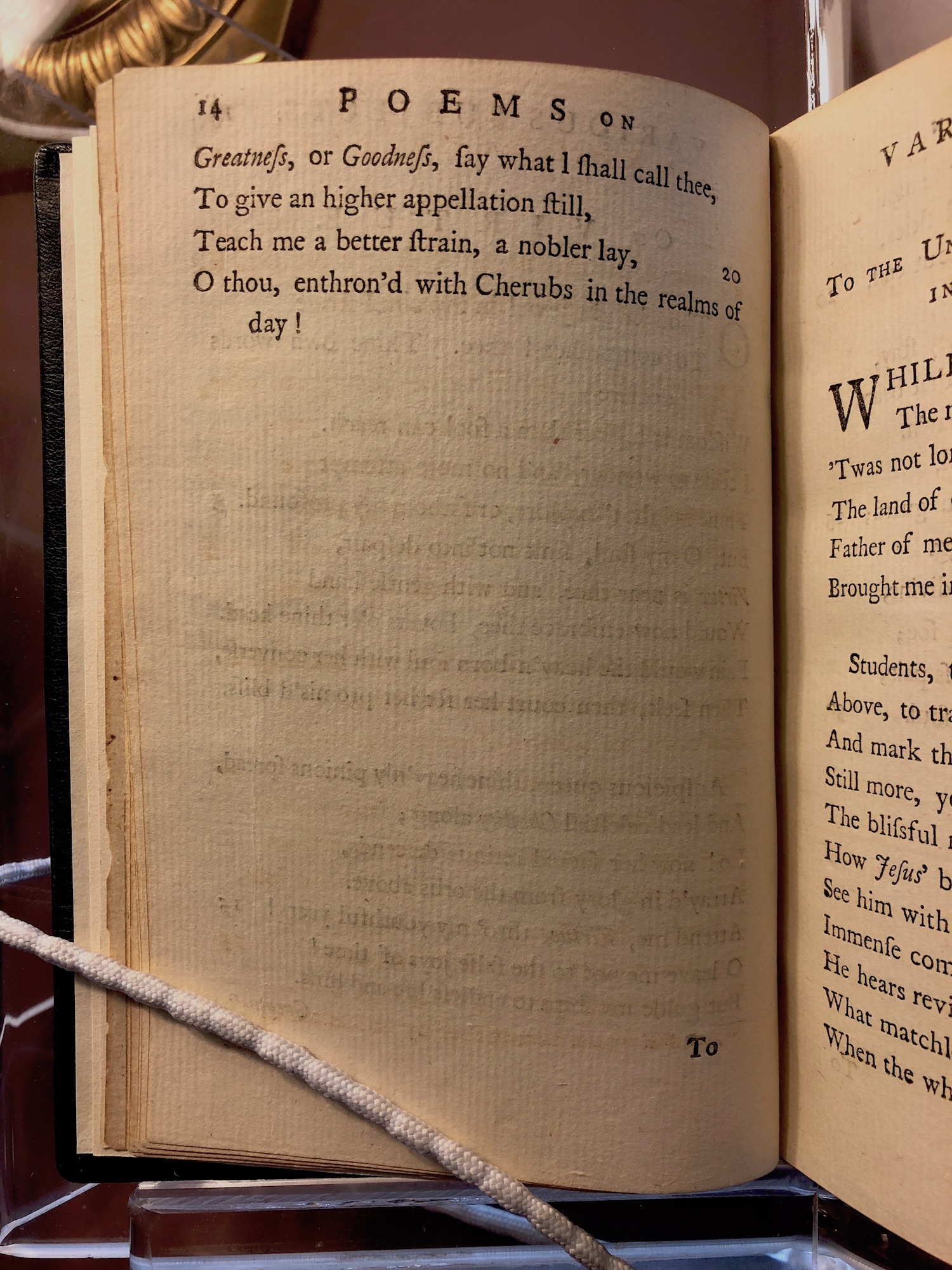

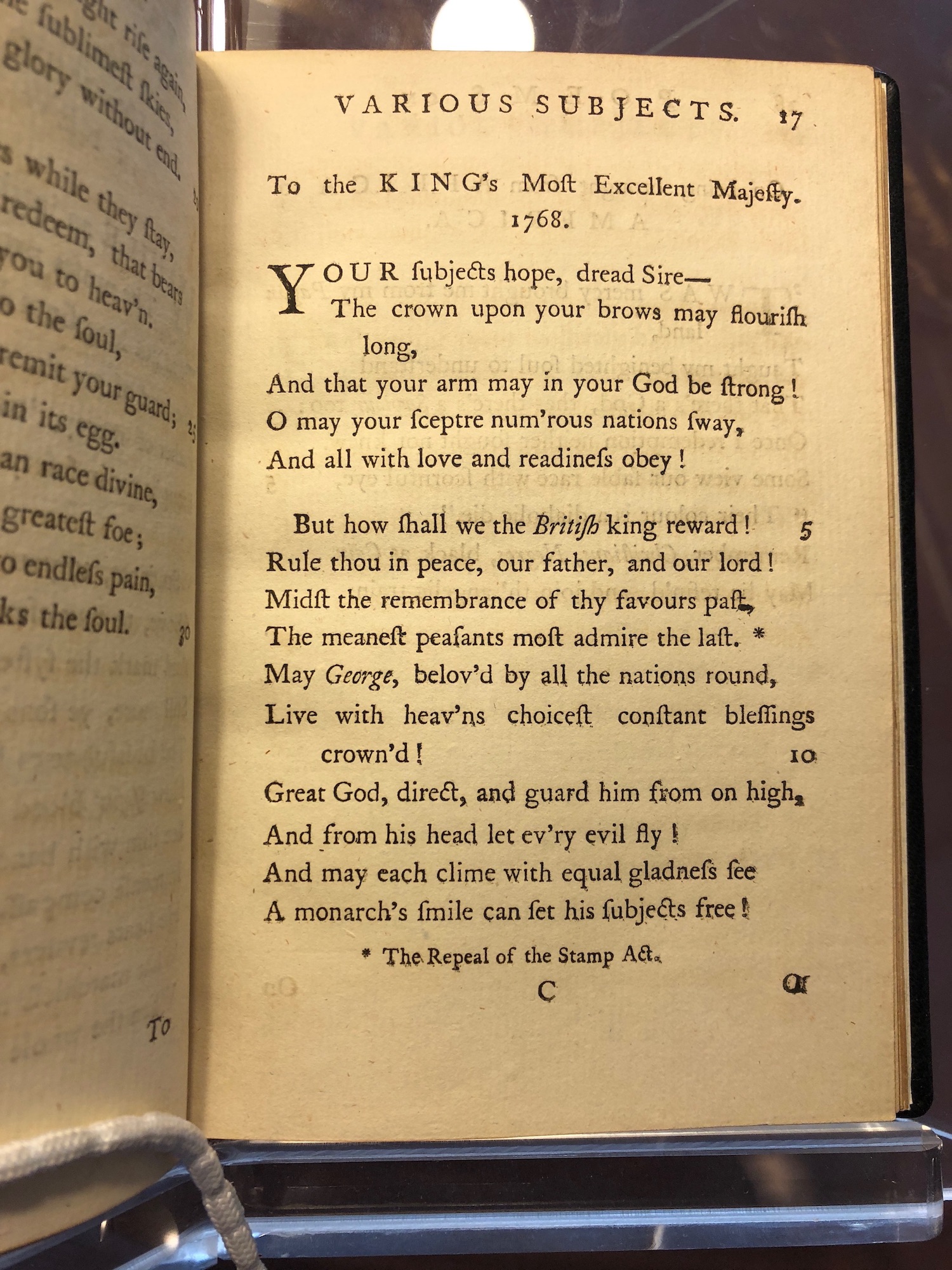

- [MUStudStaff]maecenas Source: Wheatley's 'Attestation to the Public'Maecenas was the wealthy patron of classical

Roman poets Virgil and Horace, whom Wheatley draws on in complex ways.

Wheatley's poem "To Maecenas" opens her collection, which position gives it a

powerful significance as she claims the right to speak within this tradition.

Like Horace's Odes to Maecenas, Wheatley's offers praise to her patron,

but does so in ways that are fraught with the equivocalities of being an

enslaved African working within the languge and culture of the colonial master.

For a deeper reading of "To Maecenas," see Paula Bennett's journal article,

"Phillis Wheatley's Vocation and the Paradox of the 'Afric Muse.'" Following

other scholars, Bennett identifies Wheatley's poet-patron as Mather Byles, one

of the signatories verifying her authorship. The image included here shows the

attestation to the public, included in the 1773 edition of Wheatley's poems,

certifying that they were indeed written by "PHILLIS, a young Negro Girl, who

was but a few Years since, brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa,...and now is, under the Disadvantage of serving

as a Slave in a Family in [Boston]." Note Bales' name. - [TH]homerHomer is the ancient Greek poet of The

Oddyssey and The Illiad. - [TH]achilles

Source: Wheatley's 'Attestation to the Public'Maecenas was the wealthy patron of classical

Roman poets Virgil and Horace, whom Wheatley draws on in complex ways.

Wheatley's poem "To Maecenas" opens her collection, which position gives it a

powerful significance as she claims the right to speak within this tradition.

Like Horace's Odes to Maecenas, Wheatley's offers praise to her patron,

but does so in ways that are fraught with the equivocalities of being an

enslaved African working within the languge and culture of the colonial master.

For a deeper reading of "To Maecenas," see Paula Bennett's journal article,

"Phillis Wheatley's Vocation and the Paradox of the 'Afric Muse.'" Following

other scholars, Bennett identifies Wheatley's poet-patron as Mather Byles, one

of the signatories verifying her authorship. The image included here shows the

attestation to the public, included in the 1773 edition of Wheatley's poems,

certifying that they were indeed written by "PHILLIS, a young Negro Girl, who

was but a few Years since, brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa,...and now is, under the Disadvantage of serving

as a Slave in a Family in [Boston]." Note Bales' name. - [TH]homerHomer is the ancient Greek poet of The

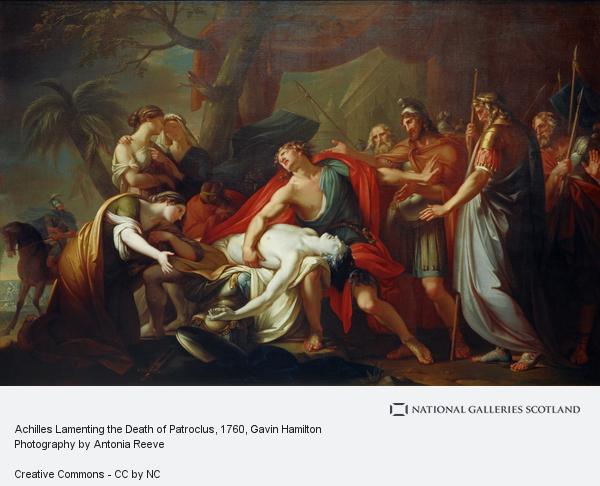

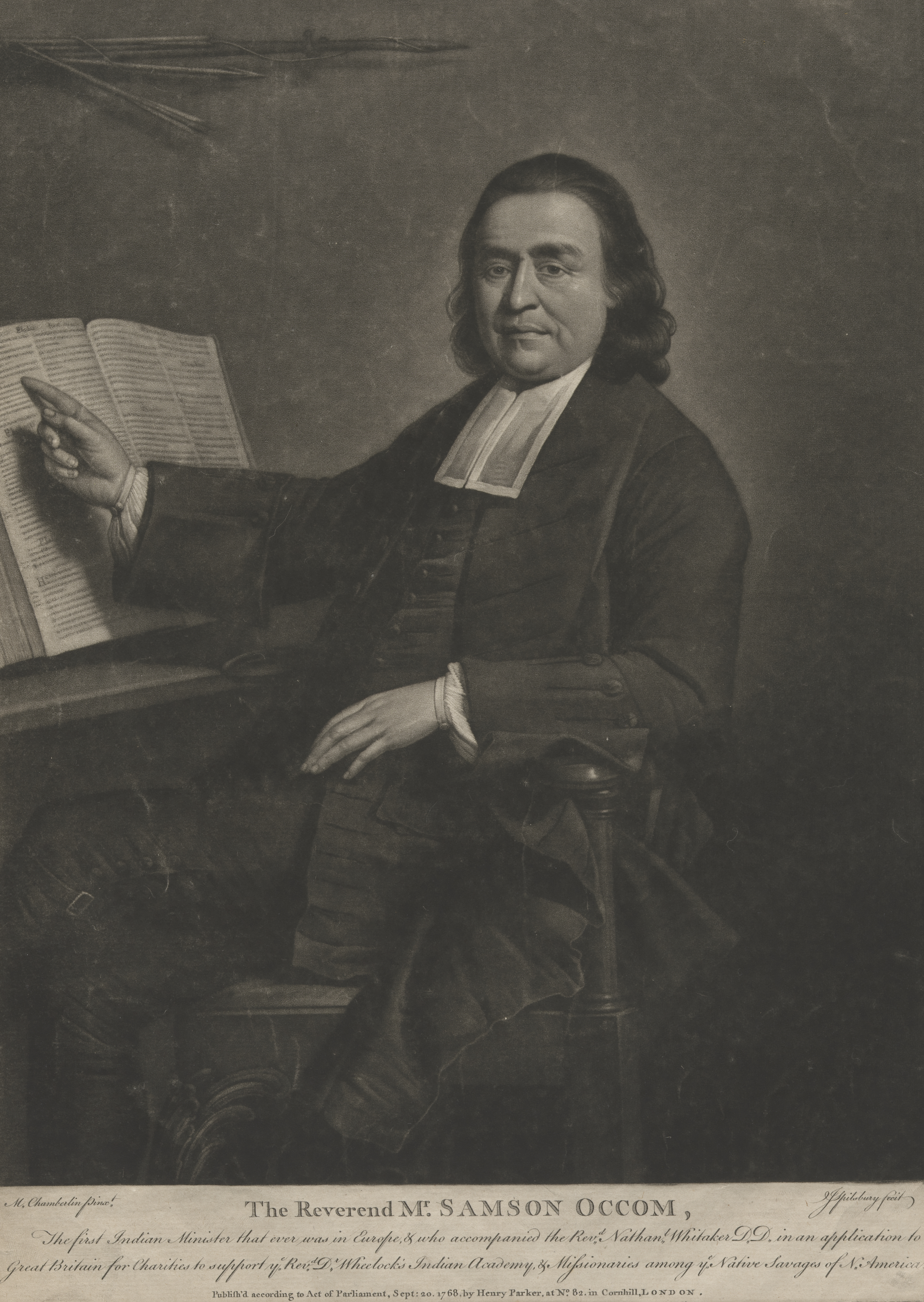

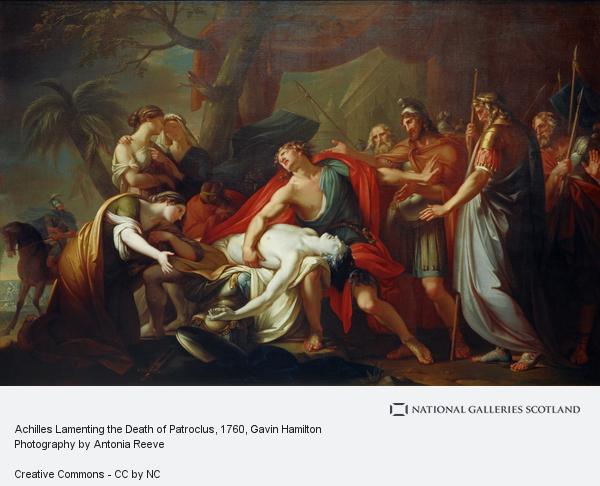

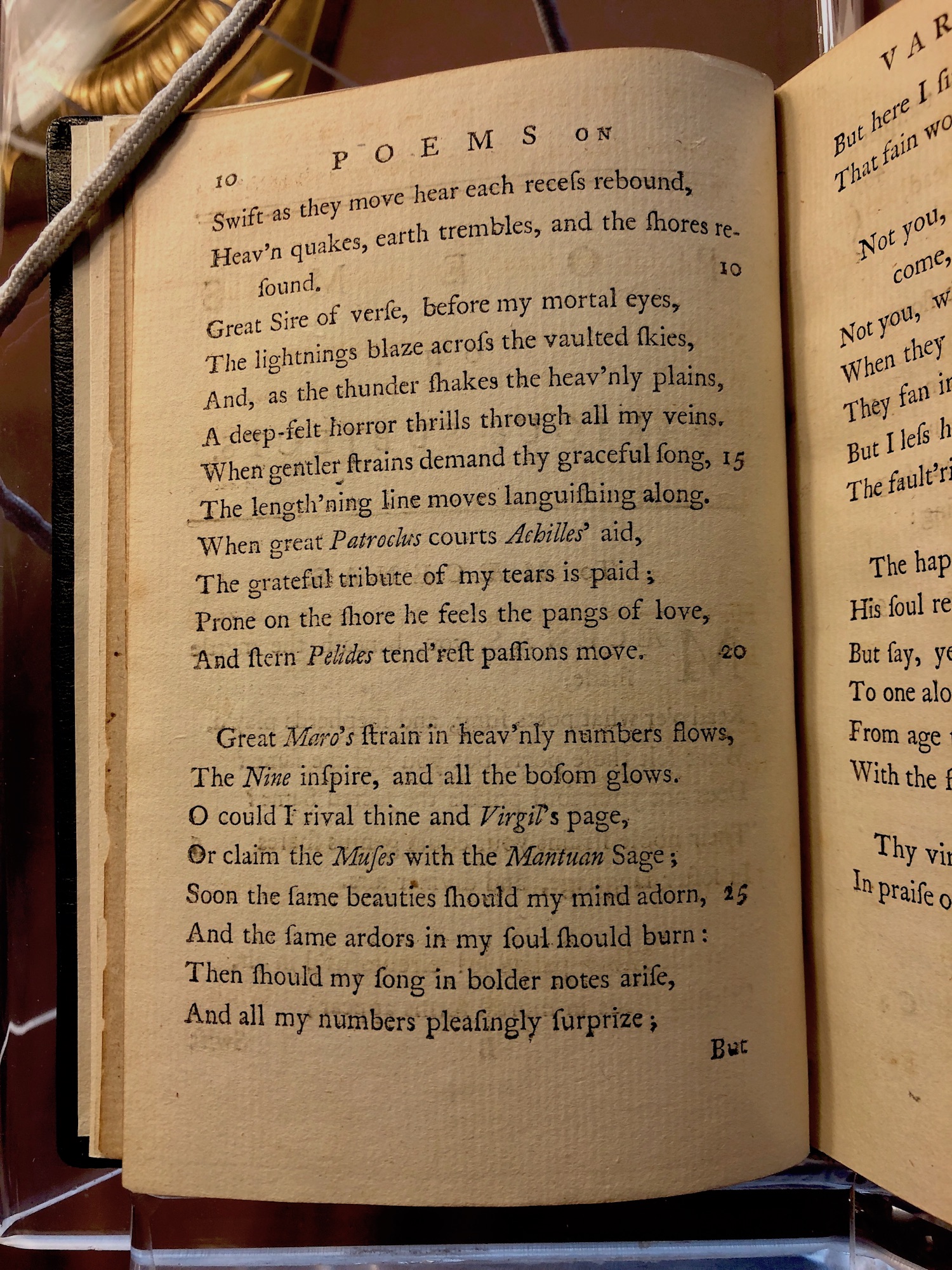

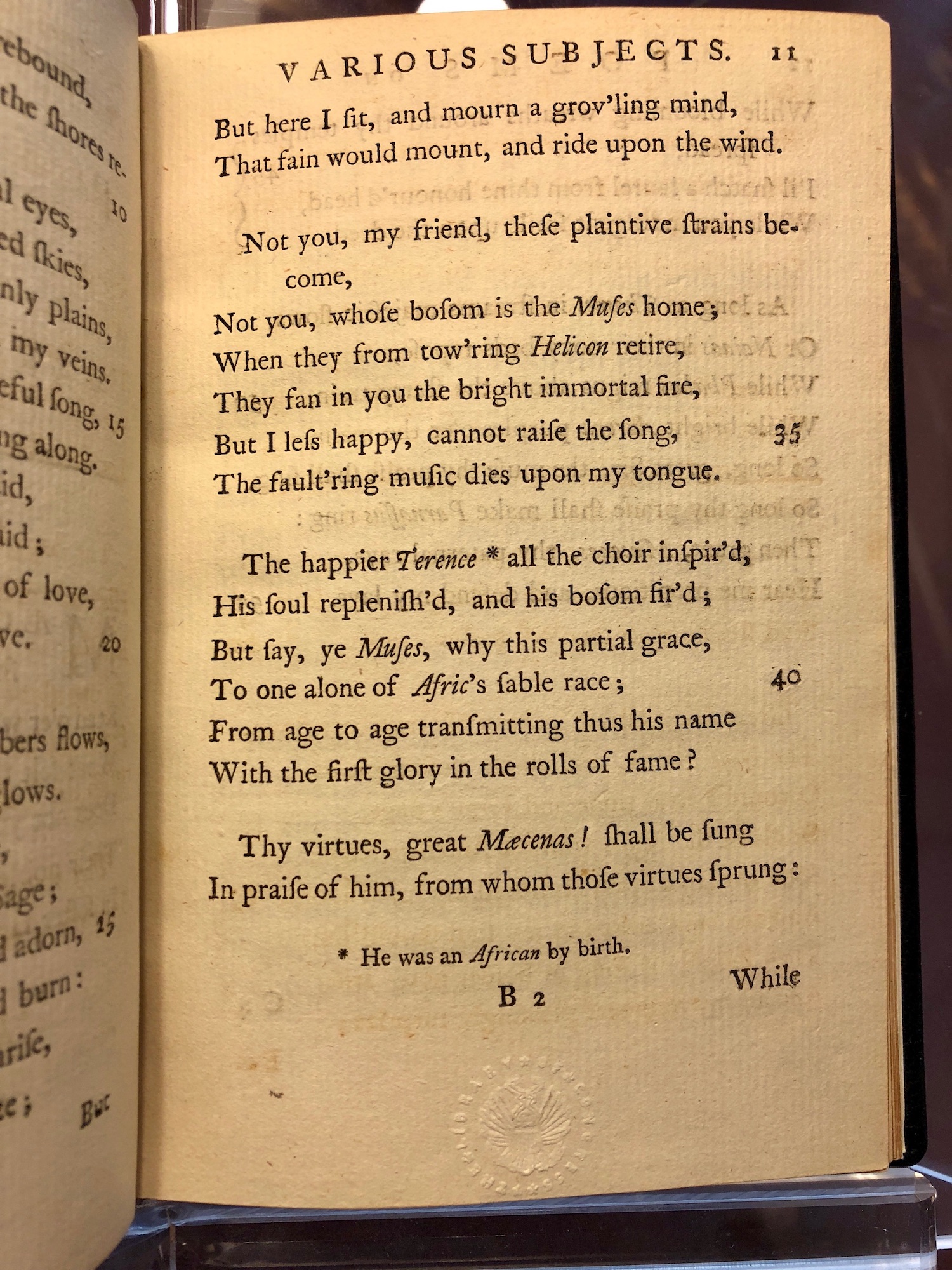

Oddyssey and The Illiad. - [TH]achilles Source: Gavin Hamilton, 'Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus' (1760-1763)Achilles is the main character of The Illiad, which tells the story of the Trojan War and,

specifically, Achilles' wrath. Achilles and Patroclus are lovers and friends;

angered by Agammemnon, Achilles refuses to fight, but allows Patroclus to wear

his armor and lead the Myrmidons against the Trojans. When Patroclus is killed

by Hector, Achilles is grief-stricken and, enraged, he returns to battle to

destroy the Trojans. The image included here, Gavin Hamilton's Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus (1760-1763), is

housed in National Galleries, Scotland. - [TH]pelidesPelides is Achilles' father; therefore, it is also

another way of referring to Achilles himself. Achilles is frequently described

as "stern" by Homer. - [TH]maroPublius Vergilius Maro, more commonly known as Virgil,

the Augustan Roman poet famed for his Eclogues and the epic poem The Aeneid. - [TH]nineThe nine muses in Greco-Roman mythology are goddesses,

daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne who inspire those in the arts and

sciences. - [TH]mantuaMantua

is a city in Italy, and the home of Virgil; the Mantuan sage is the poet

Virgil. - [TH]fainMeaning "[g]ladly,

willingly, with pleasure," according to the OED (fain, adv.B). - [TH]heliconMount Helicon in Greece is a mountain

believed to be the home of the muses and hence a place sacred to poetry. - [TH]falteringAn alternate spelling and contraction, for meter, of "faltering," meaning

unsteady or staggering. - [TH]terencePublius Terentius Afer, better known as

Terence, is a famous Roman comic playwright, born in northern Africa. As the

Encylopedia Britannicanotes, Terence was enslaved and later

freed by a Roman senator. Wheatley suggests a connection between herself and

Terence, both of African origin; yet, Terence is "happier"--both in his poetic

skill, and perhaps also in having been freed. - [TH]laurel

Source: Gavin Hamilton, 'Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus' (1760-1763)Achilles is the main character of The Illiad, which tells the story of the Trojan War and,

specifically, Achilles' wrath. Achilles and Patroclus are lovers and friends;

angered by Agammemnon, Achilles refuses to fight, but allows Patroclus to wear

his armor and lead the Myrmidons against the Trojans. When Patroclus is killed

by Hector, Achilles is grief-stricken and, enraged, he returns to battle to

destroy the Trojans. The image included here, Gavin Hamilton's Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus (1760-1763), is

housed in National Galleries, Scotland. - [TH]pelidesPelides is Achilles' father; therefore, it is also

another way of referring to Achilles himself. Achilles is frequently described

as "stern" by Homer. - [TH]maroPublius Vergilius Maro, more commonly known as Virgil,

the Augustan Roman poet famed for his Eclogues and the epic poem The Aeneid. - [TH]nineThe nine muses in Greco-Roman mythology are goddesses,

daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne who inspire those in the arts and

sciences. - [TH]mantuaMantua

is a city in Italy, and the home of Virgil; the Mantuan sage is the poet

Virgil. - [TH]fainMeaning "[g]ladly,

willingly, with pleasure," according to the OED (fain, adv.B). - [TH]heliconMount Helicon in Greece is a mountain

believed to be the home of the muses and hence a place sacred to poetry. - [TH]falteringAn alternate spelling and contraction, for meter, of "faltering," meaning

unsteady or staggering. - [TH]terencePublius Terentius Afer, better known as

Terence, is a famous Roman comic playwright, born in northern Africa. As the

Encylopedia Britannicanotes, Terence was enslaved and later

freed by a Roman senator. Wheatley suggests a connection between herself and

Terence, both of African origin; yet, Terence is "happier"--both in his poetic

skill, and perhaps also in having been freed. - [TH]laurel Source: Jonathan Richardson, 'Portrait of Alexander Pope' (1737)The leaves of the bay laurel tree were a

conventional symbol of poetic fame and acheivement originating in the

mythological tale of Daphne and

Apollo. The image included here is a portrait of the 18th century poet

Alexander Pope, wearing a crown of laurel. The portrait (c.1737), by Jonathan

Richardson, is housed in the National

Portrait Gallery, London. - [TH]thamesThe Thames is a major river flowing

through southern England and London. - [TH]naiads

Source: Jonathan Richardson, 'Portrait of Alexander Pope' (1737)The leaves of the bay laurel tree were a

conventional symbol of poetic fame and acheivement originating in the

mythological tale of Daphne and

Apollo. The image included here is a portrait of the 18th century poet

Alexander Pope, wearing a crown of laurel. The portrait (c.1737), by Jonathan

Richardson, is housed in the National

Portrait Gallery, London. - [TH]thamesThe Thames is a major river flowing

through southern England and London. - [TH]naiads Source: Jean-Francois de Troy, 'Pan and Syrinx' (1722-1724)In Greco-Roman

mythology, naiads are female freshwater nymphs. The image included here, by

Jean-Francois de Troy, shows part of the Ovidian story of Pan and Syrinx

(1722-1724). De Troy's Pan and Syrinx is housed in the

Getty Museum. - [TH]phoebusPhoebus Apollo is an important god in the Greco-Roman

tradition. He is associated with both the sun and with music and poetry. - [TH]auroraIn Greco-Roman mythology, Aurora (called Eos in the

Greek) personifies the dawn. - [TH]parnassusParnassus is a

mountain in Greece that was seen as the home of the gods, particularly Dionysus

and Apollo, as well as the Muses. The Muses are also associated with Mount

Helicon. - [TH]cambridge

Source: Jean-Francois de Troy, 'Pan and Syrinx' (1722-1724)In Greco-Roman

mythology, naiads are female freshwater nymphs. The image included here, by

Jean-Francois de Troy, shows part of the Ovidian story of Pan and Syrinx

(1722-1724). De Troy's Pan and Syrinx is housed in the

Getty Museum. - [TH]phoebusPhoebus Apollo is an important god in the Greco-Roman

tradition. He is associated with both the sun and with music and poetry. - [TH]auroraIn Greco-Roman mythology, Aurora (called Eos in the

Greek) personifies the dawn. - [TH]parnassusParnassus is a

mountain in Greece that was seen as the home of the gods, particularly Dionysus

and Apollo, as well as the Muses. The Muses are also associated with Mount

Helicon. - [TH]cambridge

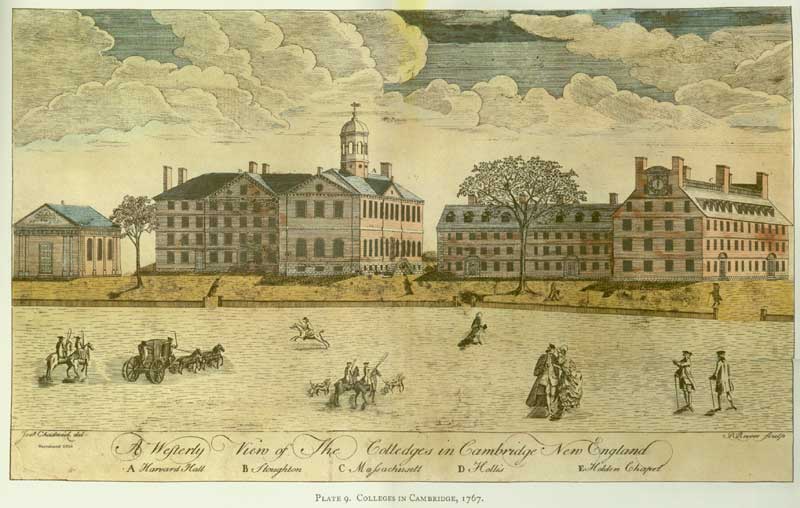

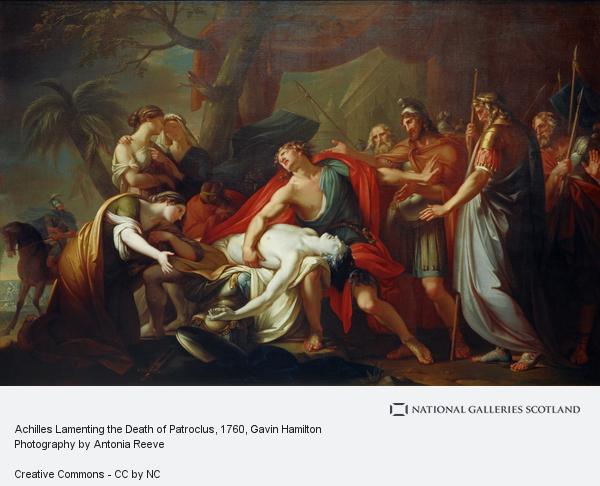

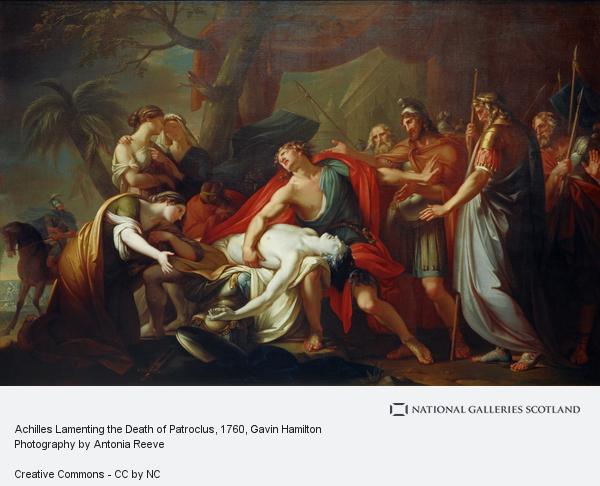

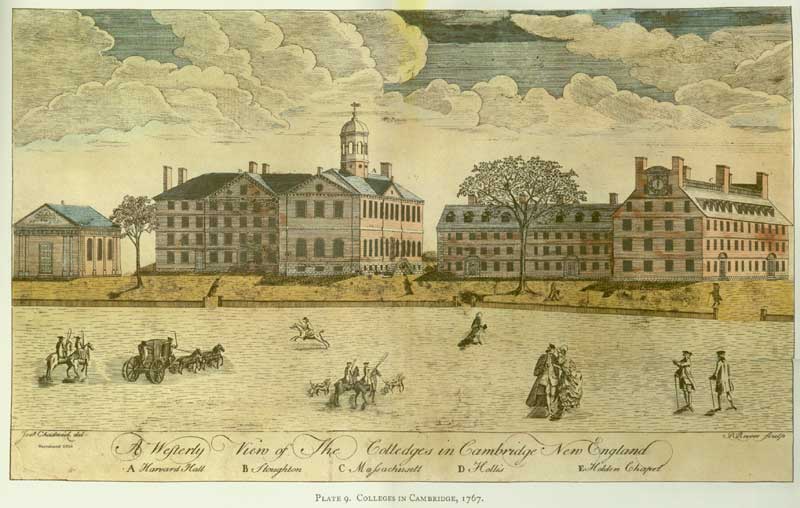

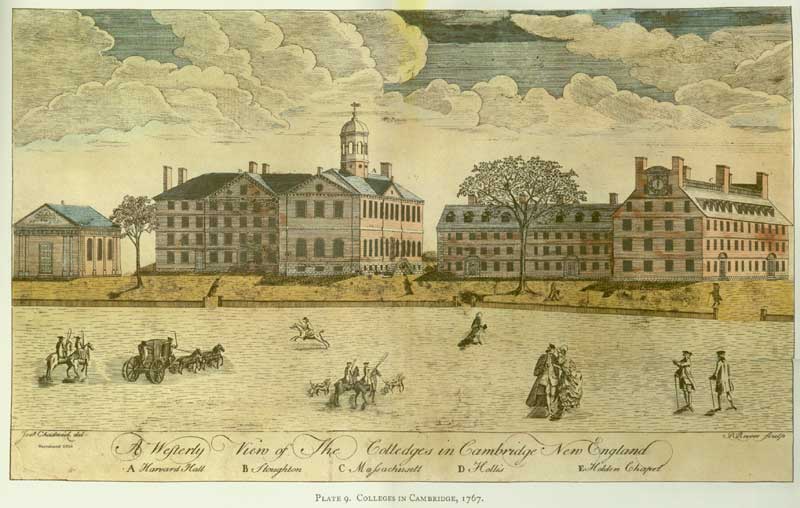

Source: Paul Revere, 'A Westerley View of the Colledges in Cambridge, New England' (1767)After describing her own educational journey, Wheatley

advises students at the University of Cambridge in New England to appreciate

and "[i]mprove" (21) the privilege of their education by "shunn[ing]" (25) the

"transient sweetness" (29) of sin using a variety of religious images. The

University of Cambridge in New England is now known as Harvard University. According to

Katherine Clay Bassard, Wheatley wrote this poem when she was about

fourteen years old (41). The engraving included here is by Paul Revere and

shows "A Westerly View of The Colledges in Cambridge New England" (1767), via

NYPL Digital Collections. - [JW]ardorWheatley works from the premise, commonly used among early women writers

and the enslaved who were restricted from intellectual pursuits like

writing, that her desire to write is "intrinsic" (1) or God-given, and

therefore appropriate. The word "ardor" also connotes physical desire and

flame-like passion, according to the OED (n.3). - [JW]musesAccording to A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology, the Muses are “inspiring goddesses of song" who

“presid[e] over the different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and

sciences." The “invocation of the muse” to aid the poet's work is often used

by neoclassical authors like those whom Wheatley has clearly read and was

influenced by, including Milton and Pope.

However, Hilene Flanzbaum suggests that Wheatley’s notably frequent

invocation of the muse is more significant than formulaic or imitative--it

is “the very means by which she usurps power for herself and claims a berth

for her own thoughts, emotions and desires. And while some may claim that

these functions accompany any appearance of the muse, when the muses bestow

their power on a black female slave, they transport Wheatley to a domain

surprisingly free of restriction and previously forbidden” (“Unprecedented Liberties”

75). - [JW]egyptianWheatley here

alludes to Exodus

10:21-22, wherein the ninth plague of darkness is visited upon

Egypt. This reference is also in line with contemporary Orientalist notions

about Egypt and Egyptian religiosity, which was believed to be full of

occult practices. Early nineteenth-century British historian and scholar

Thomas Maurice explores these ideas of idolatry and superstition in Observations on

the Remains of Ancient Egyptian Grandeur and Superstition. A

detailed focus on the Egyptian religious practices can be found in the

chapter "Strictures on the superstitious rites of the Egyptians,

particularly on the Nefarious Worship paid to Beasts, Esteemed Sacred, and

called in Scripture the Abominations of Egypt" (74-83). - [JW]systems

Source: Paul Revere, 'A Westerley View of the Colledges in Cambridge, New England' (1767)After describing her own educational journey, Wheatley

advises students at the University of Cambridge in New England to appreciate

and "[i]mprove" (21) the privilege of their education by "shunn[ing]" (25) the

"transient sweetness" (29) of sin using a variety of religious images. The

University of Cambridge in New England is now known as Harvard University. According to

Katherine Clay Bassard, Wheatley wrote this poem when she was about

fourteen years old (41). The engraving included here is by Paul Revere and

shows "A Westerly View of The Colledges in Cambridge New England" (1767), via

NYPL Digital Collections. - [JW]ardorWheatley works from the premise, commonly used among early women writers

and the enslaved who were restricted from intellectual pursuits like

writing, that her desire to write is "intrinsic" (1) or God-given, and

therefore appropriate. The word "ardor" also connotes physical desire and

flame-like passion, according to the OED (n.3). - [JW]musesAccording to A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology, the Muses are “inspiring goddesses of song" who

“presid[e] over the different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and

sciences." The “invocation of the muse” to aid the poet's work is often used

by neoclassical authors like those whom Wheatley has clearly read and was

influenced by, including Milton and Pope.

However, Hilene Flanzbaum suggests that Wheatley’s notably frequent

invocation of the muse is more significant than formulaic or imitative--it

is “the very means by which she usurps power for herself and claims a berth

for her own thoughts, emotions and desires. And while some may claim that

these functions accompany any appearance of the muse, when the muses bestow

their power on a black female slave, they transport Wheatley to a domain

surprisingly free of restriction and previously forbidden” (“Unprecedented Liberties”

75). - [JW]egyptianWheatley here

alludes to Exodus

10:21-22, wherein the ninth plague of darkness is visited upon

Egypt. This reference is also in line with contemporary Orientalist notions

about Egypt and Egyptian religiosity, which was believed to be full of

occult practices. Early nineteenth-century British historian and scholar

Thomas Maurice explores these ideas of idolatry and superstition in Observations on

the Remains of Ancient Egyptian Grandeur and Superstition. A

detailed focus on the Egyptian religious practices can be found in the

chapter "Strictures on the superstitious rites of the Egyptians,

particularly on the Nefarious Worship paid to Beasts, Esteemed Sacred, and

called in Scripture the Abominations of Egypt" (74-83). - [JW]systems Source: Joseph Wright, 'Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery' (1766)The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

development of the microscope and the telescope had made great scientific

advancements possible, especially in astronomy; in the painting by Joseph

Wright here, you can see an eighteenth-century orrery--a scientific

clockwork instrument used to dramatize the motion of the planets in the

solar system (via Wikimedia Commons). Possibly an allusion to Alexander

Pope's 1733-34 Essay on Man (I.23-28), Wheatley here may

also be referencing contemporary scientific thought about the plurality of worlds. - [JW]deign According to the

Oxford English Dictionary deign means "to think it worthy of oneself" or "to think fit"

(n.1a). Today, it typically has a negative connotation, though it does not

here. - [JW]ethiop

Source: Joseph Wright, 'Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery' (1766)The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

development of the microscope and the telescope had made great scientific

advancements possible, especially in astronomy; in the painting by Joseph

Wright here, you can see an eighteenth-century orrery--a scientific

clockwork instrument used to dramatize the motion of the planets in the

solar system (via Wikimedia Commons). Possibly an allusion to Alexander

Pope's 1733-34 Essay on Man (I.23-28), Wheatley here may

also be referencing contemporary scientific thought about the plurality of worlds. - [JW]deign According to the

Oxford English Dictionary deign means "to think it worthy of oneself" or "to think fit"

(n.1a). Today, it typically has a negative connotation, though it does not

here. - [JW]ethiop

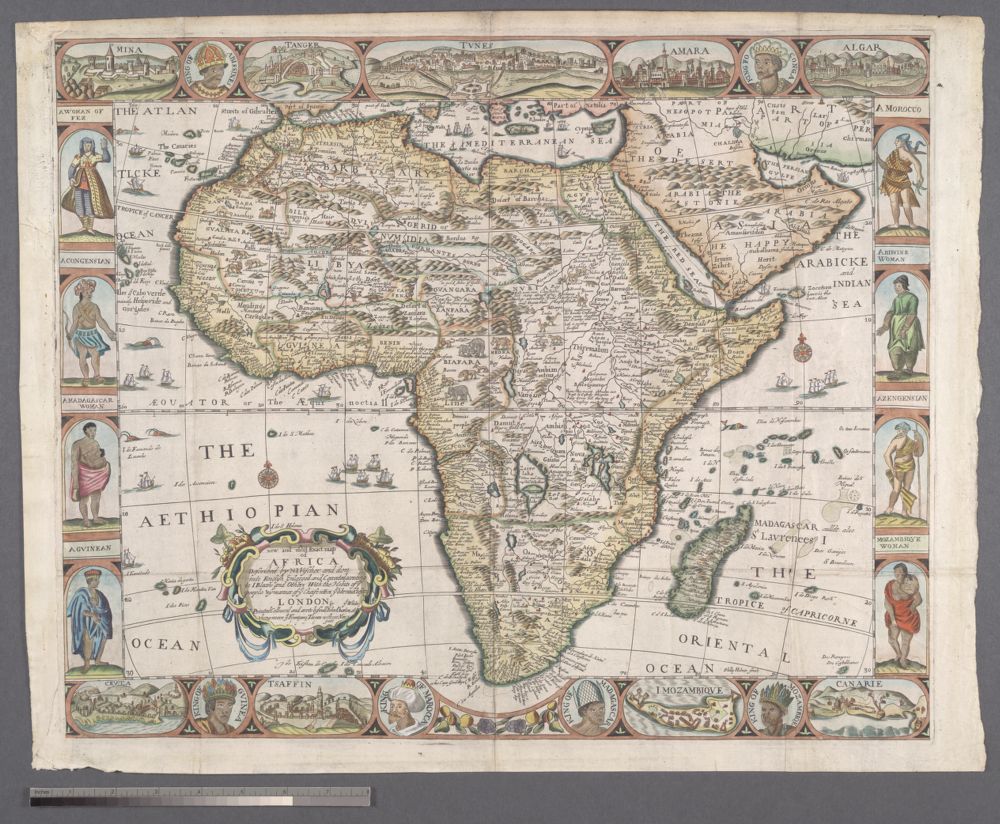

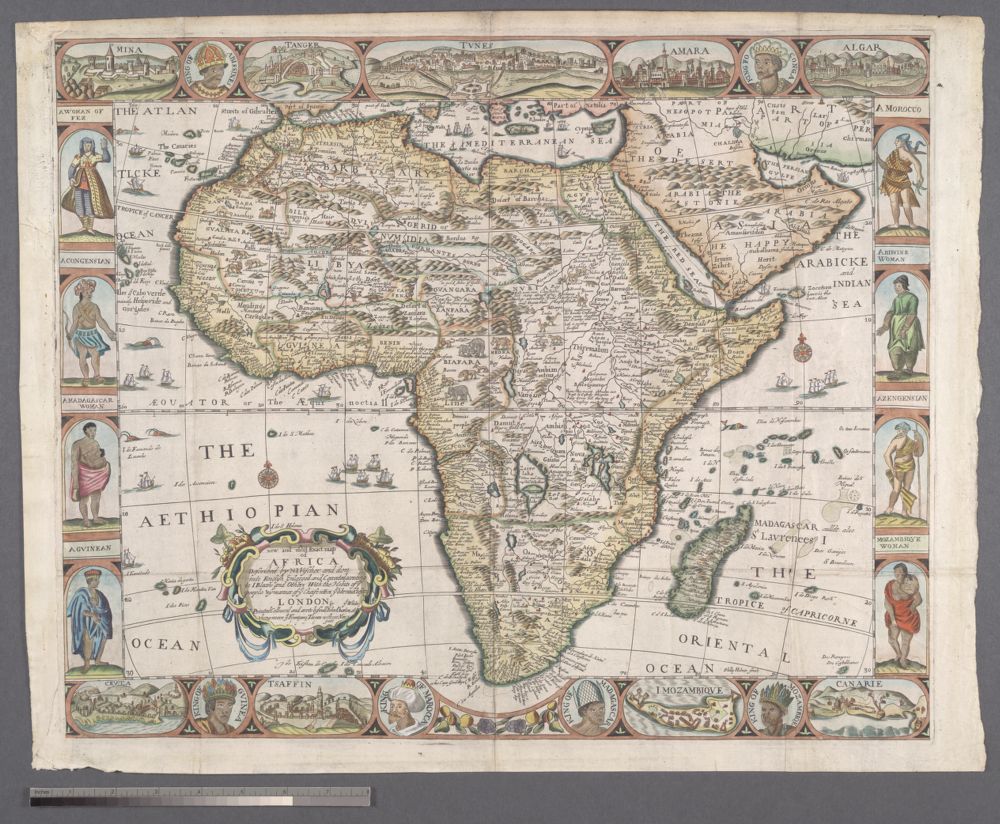

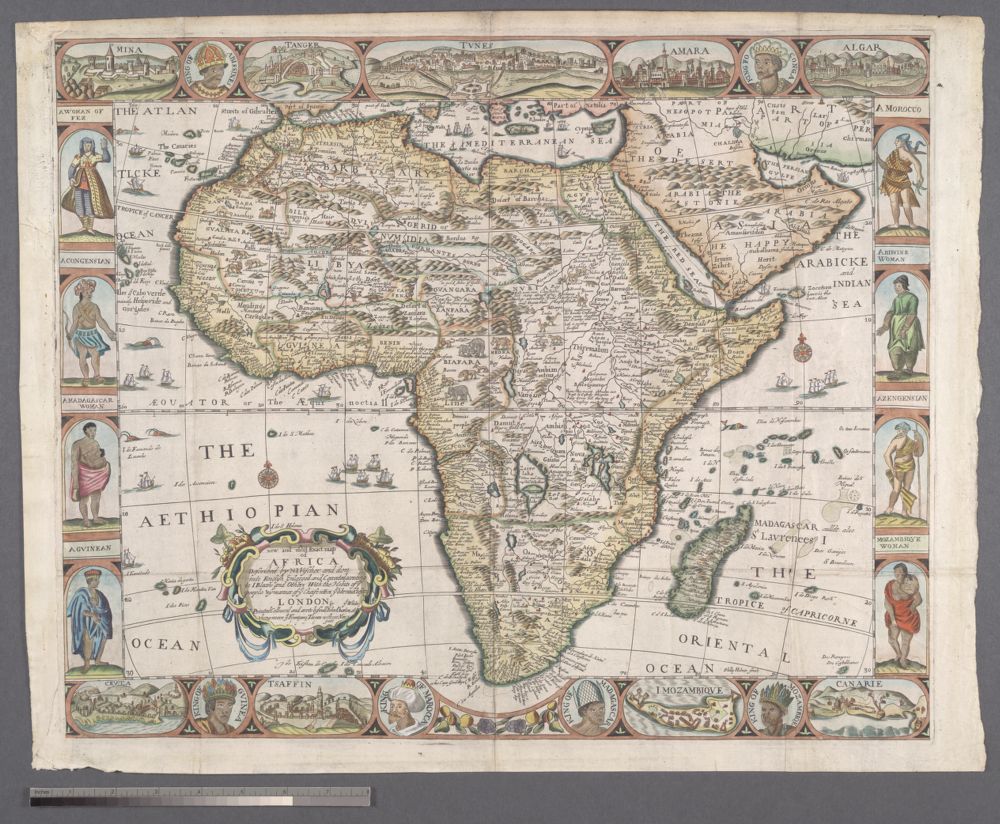

Source: John Overton, 'A new and most exact map of Africa' (1666)According

to the OED, the word Ethiop would

have been used during Wheatley's time most often to refer to "[a] black or

dark-skinned person; a black African," and only occasionally to the country

of Ethiopia, specifically (n.A). Included here, via the Norwich Collection at Stanford University, is a 1666 map

of Africa and the surrounding oceans, embellished with a variety of images.

- [JW]perditionIn theological discussion, the word perdition means "the

state of final spiritual ruin or damnation; the consignment of the

unredeemed or wicked and impenitent soul to hell; the fate of those in hell;

eternal death" (OED, "perdition" n.2a). In more general terms, it suggests

ruin or degradation (n.1a). - [JW]brought

Source: John Overton, 'A new and most exact map of Africa' (1666)According

to the OED, the word Ethiop would

have been used during Wheatley's time most often to refer to "[a] black or

dark-skinned person; a black African," and only occasionally to the country

of Ethiopia, specifically (n.A). Included here, via the Norwich Collection at Stanford University, is a 1666 map

of Africa and the surrounding oceans, embellished with a variety of images.

- [JW]perditionIn theological discussion, the word perdition means "the

state of final spiritual ruin or damnation; the consignment of the

unredeemed or wicked and impenitent soul to hell; the fate of those in hell;

eternal death" (OED, "perdition" n.2a). In more general terms, it suggests

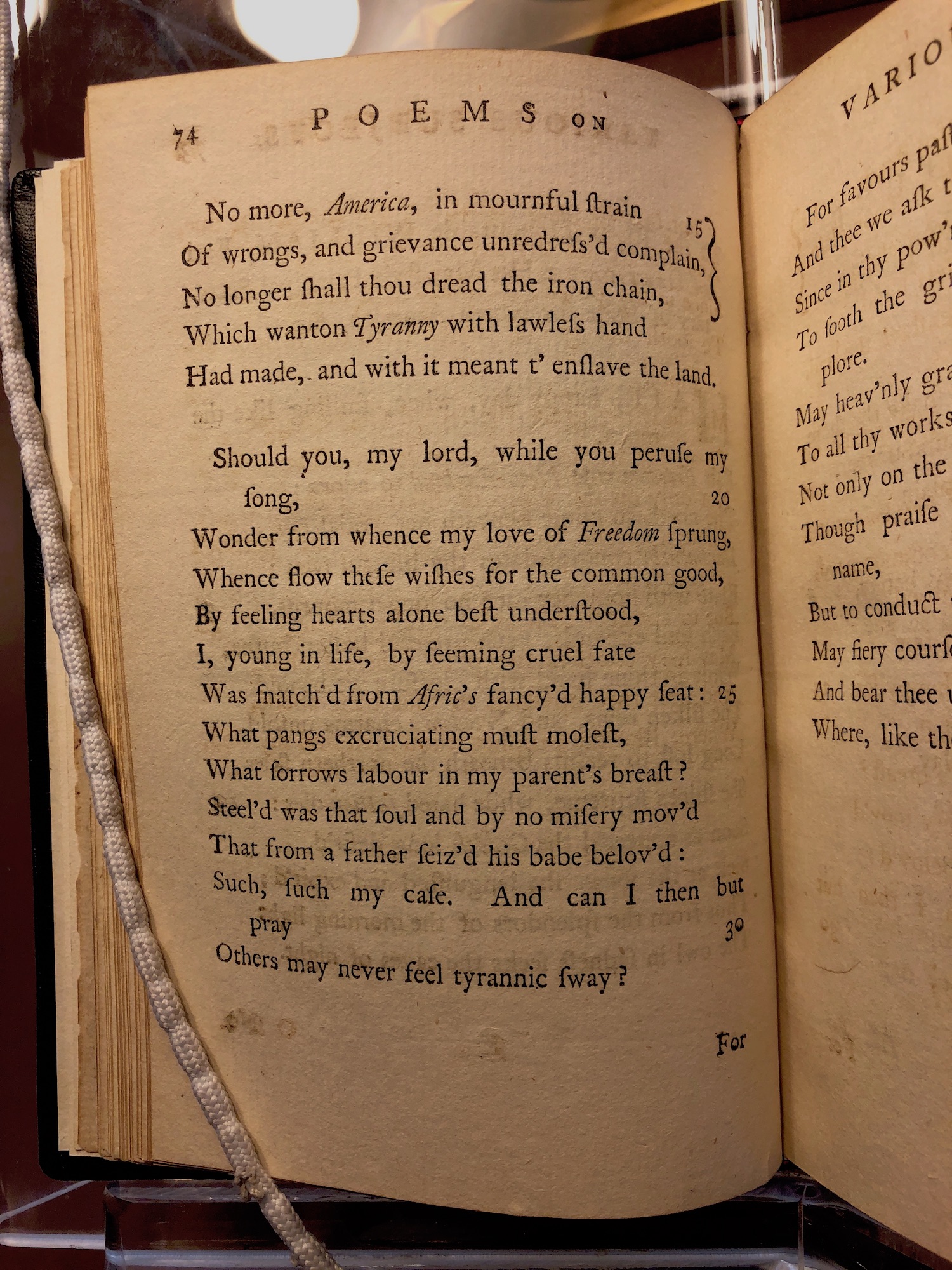

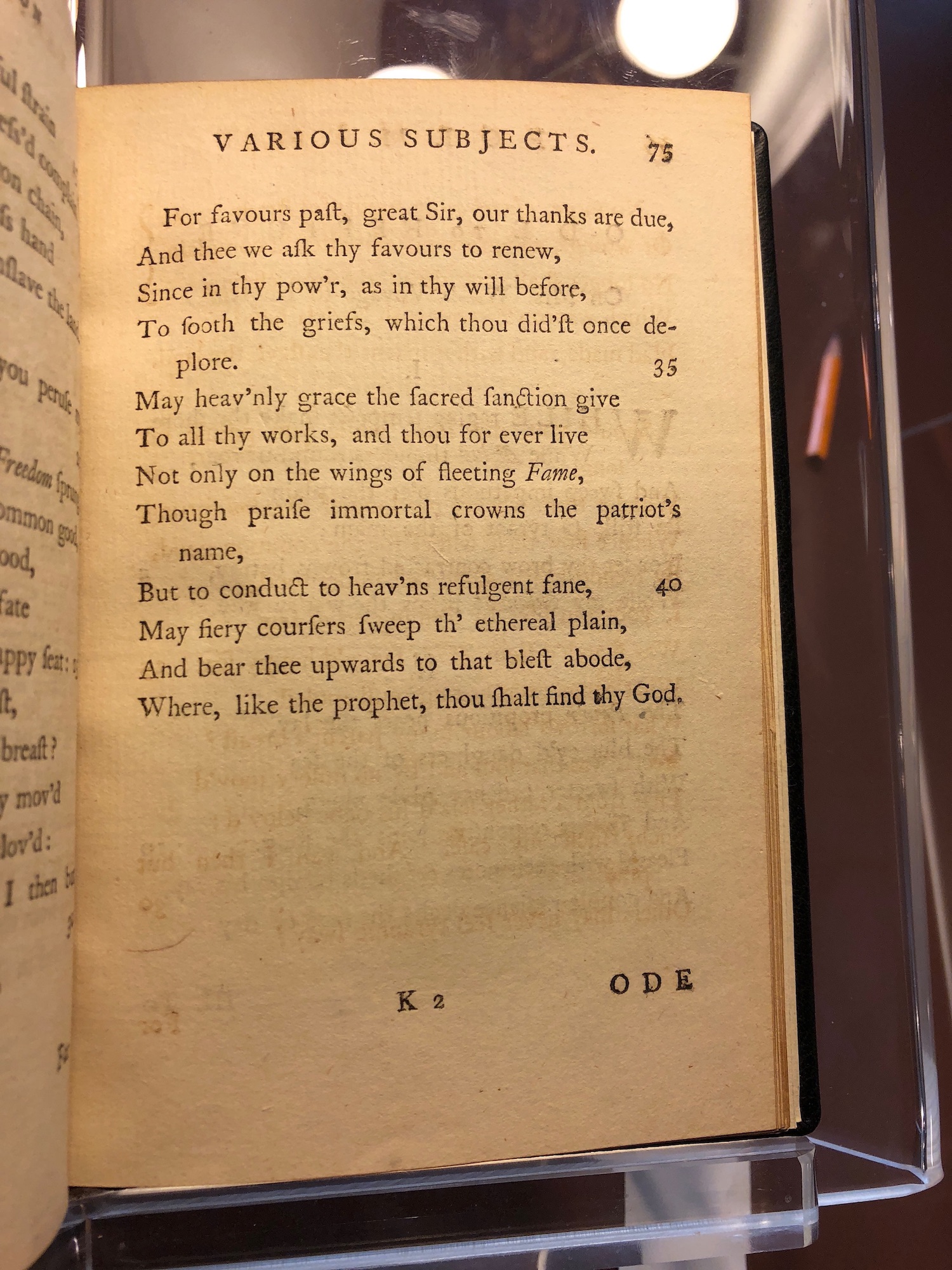

ruin or degradation (n.1a). - [JW]brought The title of one Wheatley's most (in)famous poems, "On being brought from

AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the experiences of many Africans who became

subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801). - [JW]viewWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

- [TH]cainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)

- [JW]whitfield

The title of one Wheatley's most (in)famous poems, "On being brought from

AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the experiences of many Africans who became

subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801). - [JW]viewWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

- [TH]cainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)

- [JW]whitfield

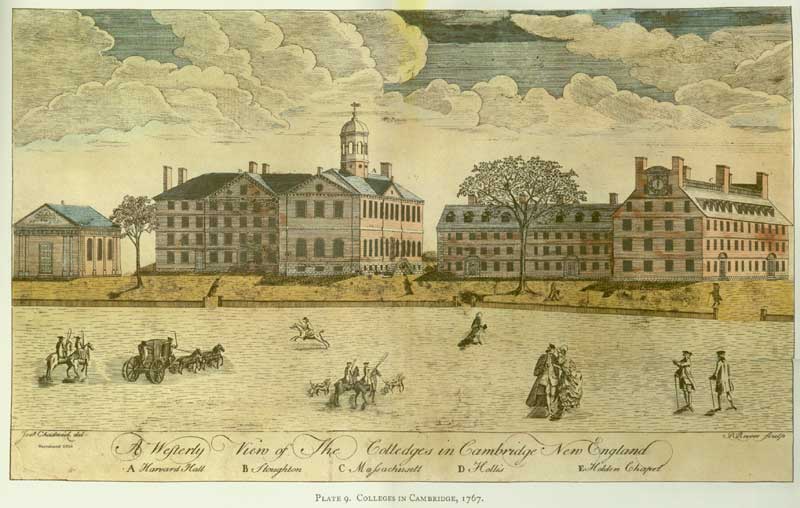

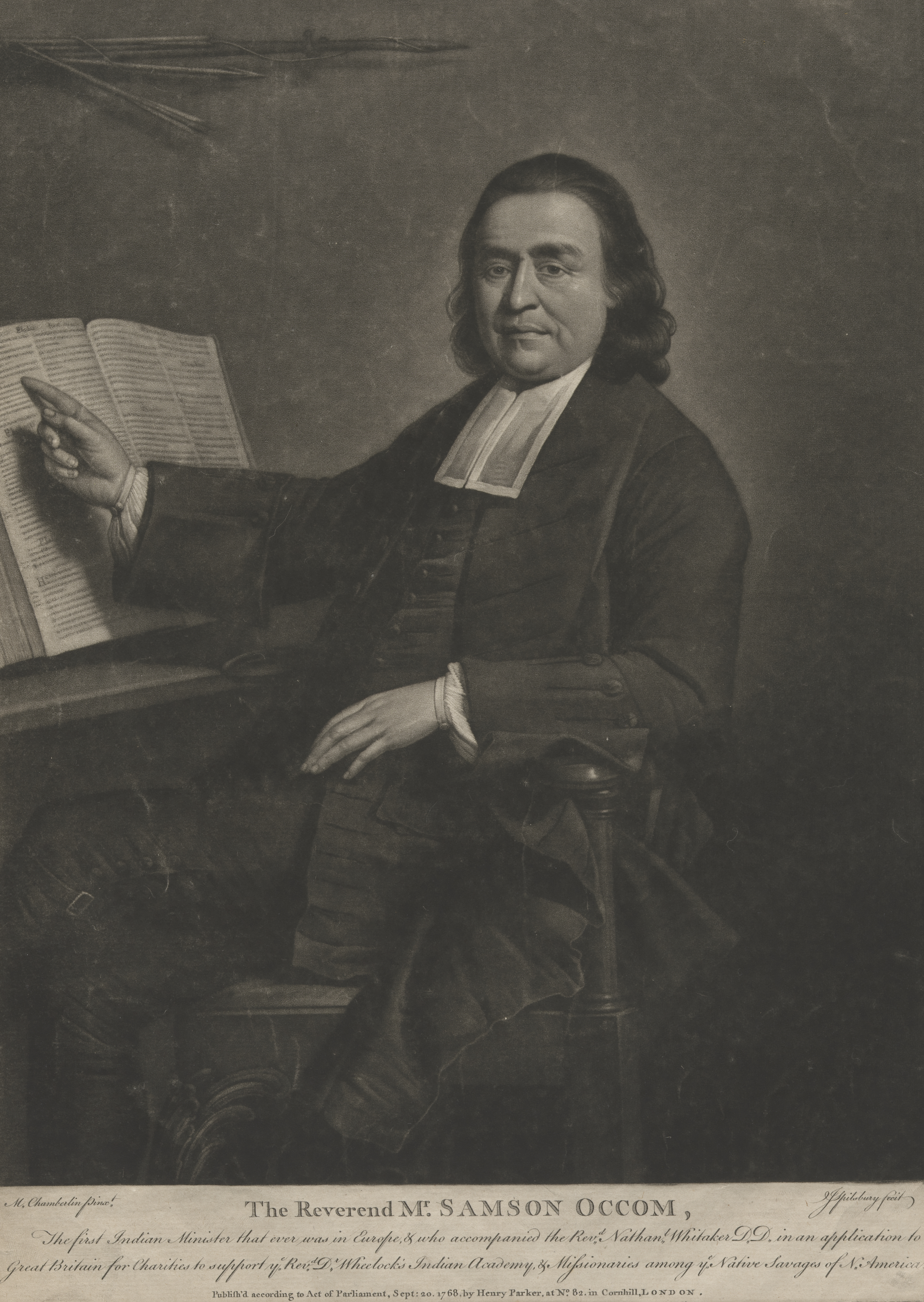

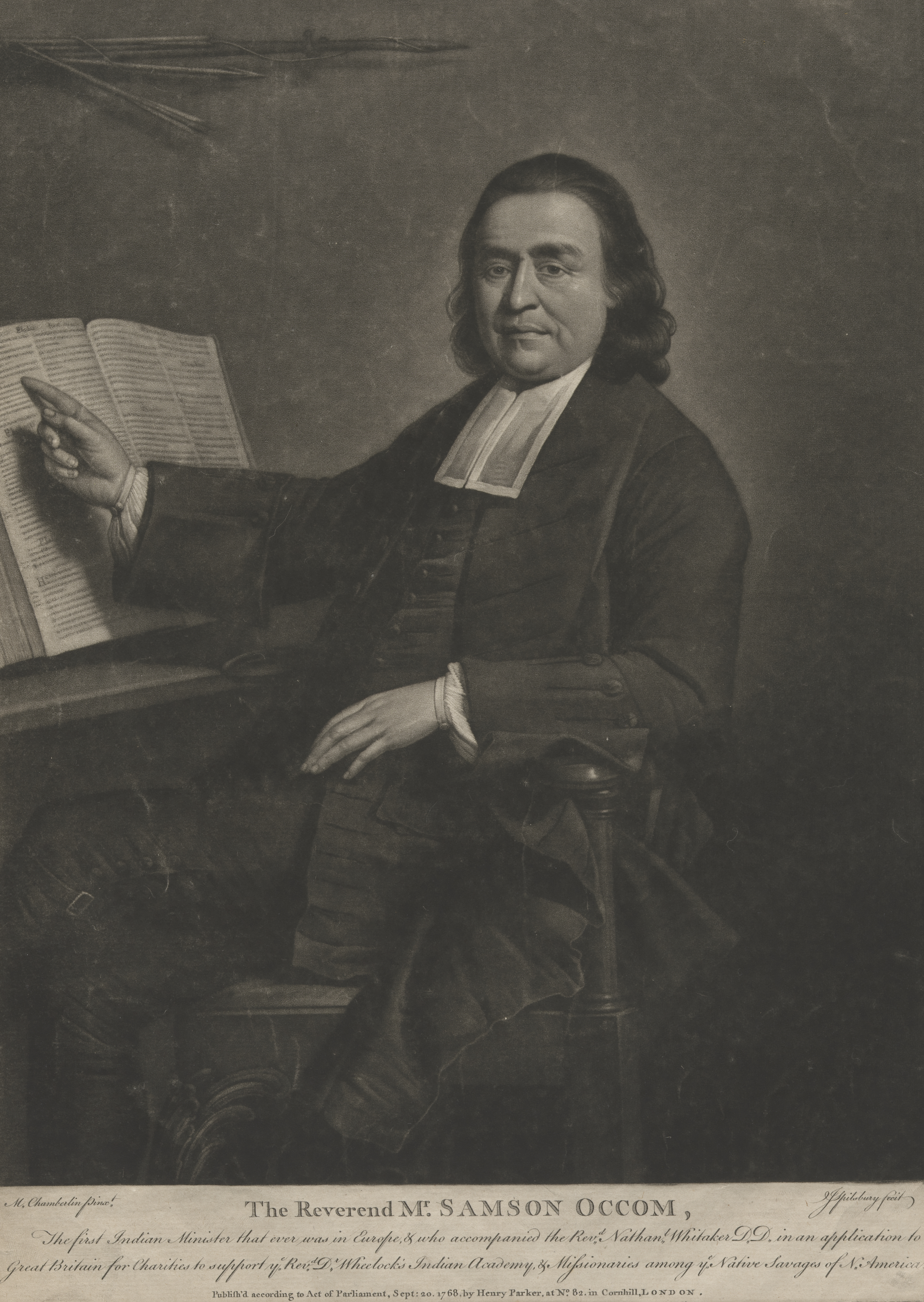

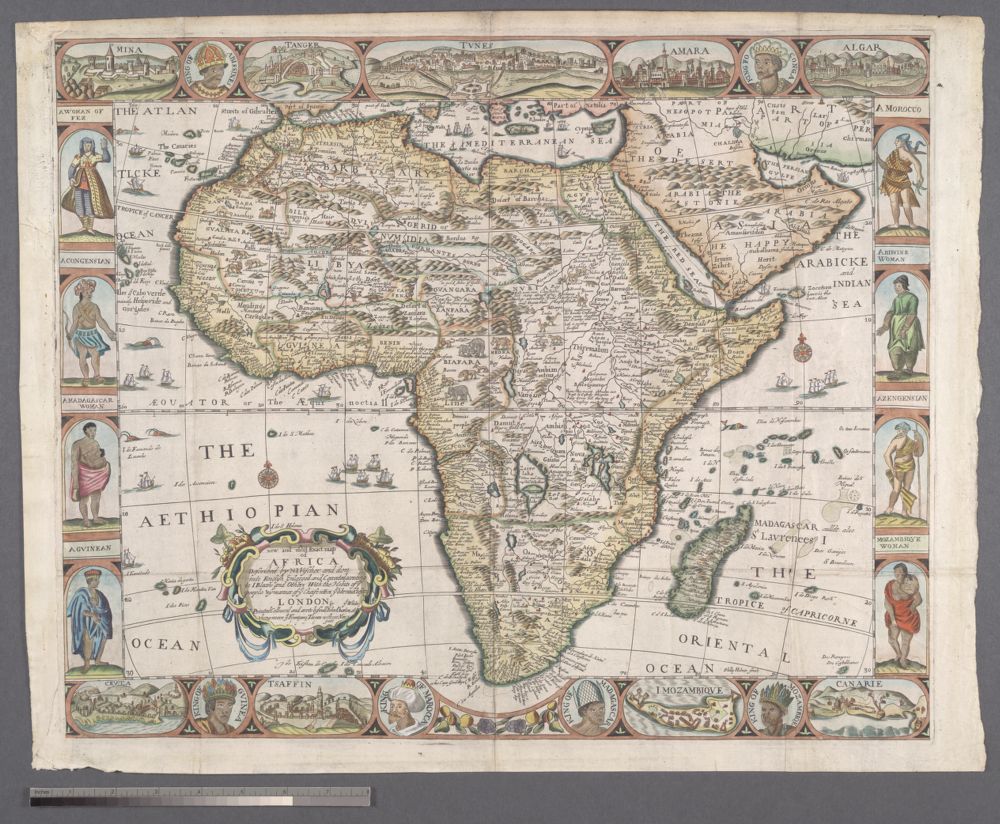

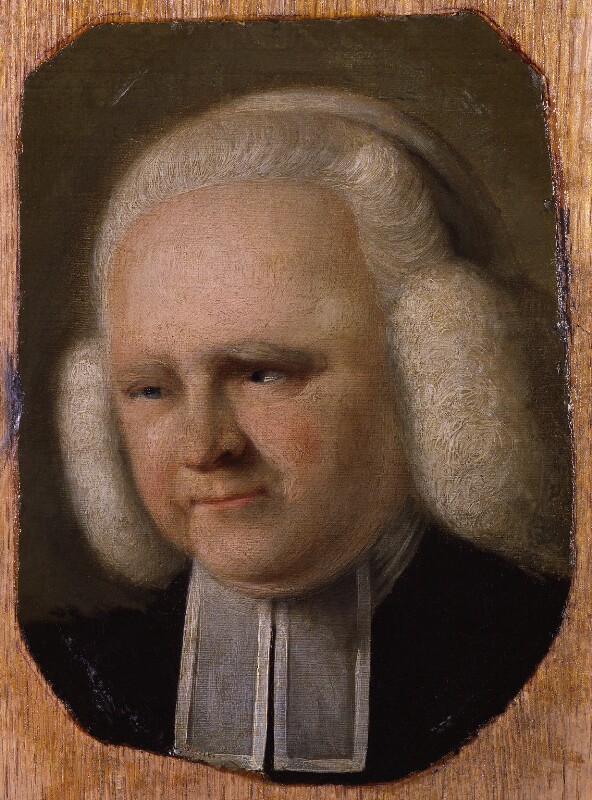

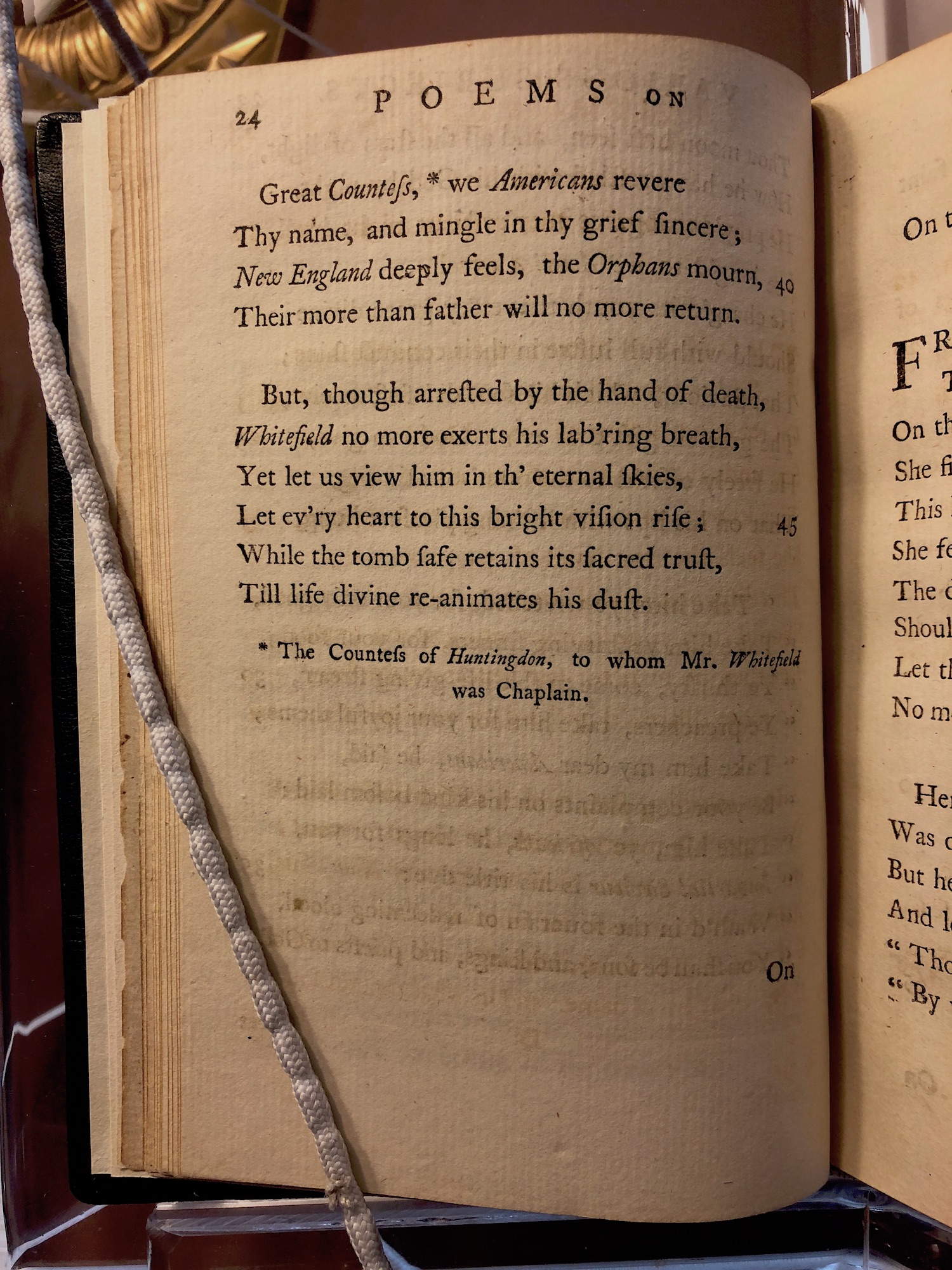

Source: John Russell, 'Portrait of George Whitefield' (c.1770)

George Whitefield (1714-1770; pronounced "wit-field") was one of the most

famous people of the eighteenth-century Anglophone world. As a student at

Oxford in the early 1730s, he got to know John and Charles Wesley, the founders

of the Methodist movement in the church of England. Whitefield joined them in

attempting to "methodize" the faith, returning it to the simple principles of

the early church. But more than the Wesley brothers, Whitefield made this

reformist movement into a public ministry. A famously charismatic public

speaker, Whitefield preached to crowds numbering in the thousands in England

and the American colonies, becoming a central figure in what was known as the

"Great Awakening," a revival of evangelical Protestantism that was influential

on both sides of the Atlantic. Benjamin Franklin and Olaudah Equiano were each

impressed (though in very different ways) when they saw Whitefield preach in

Philadelphia and Savannah, respectively. Whitefield made several visits to the

Boston area, and it seems likely that the Wheatleys saw him preach there.

Phillis might very well have joined them, but we cannot be sure. Whitefield

died unexpectedly in Newburyport, Massachusetts on September 30, 1770, a few

days after he left Boston on what turned out to be his last tour of the

colonies.

Phillis Wheatley's elegy for Whitefield changed her life, transforming her from

a young enslaved woman with a small readership among friends of the Wheatley

family to an author with an international readership. The poem was published as

a broadside on October 11, 1770, and was an immediate success. It was reprinted

several times in colonial cities, as well as London, and also appeared in

several newspapers. The poem brought Wheatley to the attention of Selina, the

Countess of Huntingdon, who is addressed in the poem itself. A fervent

Methodist herself, the Countess was Whitefield's patron, supporting him on his

evangelical missions. The Countess became Wheatley's patron as well, sponsoring

the publication of her only volume of poems, published in London in 1773. The image included here shows a portrait of Whitefield by John Russel, from the National Portrait Gallery, UK.

- [JOB]wontedwonted:

"Accustomed, customary, usual." Oxford English Dictionary;

auditory: "An assembly of hearers, an audience." Oxford English

Dictionary, hence the meaning here is something like "usual audience." - [JOB]unequalled"unequalled accents"; Whitefield was a famously eloquent and compelling public

speaker; the sense here is that no other speaker could match the "accent" or style of

his voice. - [JOB]zionZion is a

name in the Hebrew bible for Jerusalem, and the term has often been extended to mean

the entirety of what believers think of as the holy land, or even the

afterlife. - [JOB]countess

Source: John Russell, 'Portrait of George Whitefield' (c.1770)

George Whitefield (1714-1770; pronounced "wit-field") was one of the most

famous people of the eighteenth-century Anglophone world. As a student at

Oxford in the early 1730s, he got to know John and Charles Wesley, the founders

of the Methodist movement in the church of England. Whitefield joined them in

attempting to "methodize" the faith, returning it to the simple principles of

the early church. But more than the Wesley brothers, Whitefield made this

reformist movement into a public ministry. A famously charismatic public

speaker, Whitefield preached to crowds numbering in the thousands in England

and the American colonies, becoming a central figure in what was known as the

"Great Awakening," a revival of evangelical Protestantism that was influential

on both sides of the Atlantic. Benjamin Franklin and Olaudah Equiano were each

impressed (though in very different ways) when they saw Whitefield preach in

Philadelphia and Savannah, respectively. Whitefield made several visits to the

Boston area, and it seems likely that the Wheatleys saw him preach there.

Phillis might very well have joined them, but we cannot be sure. Whitefield

died unexpectedly in Newburyport, Massachusetts on September 30, 1770, a few

days after he left Boston on what turned out to be his last tour of the

colonies.

Phillis Wheatley's elegy for Whitefield changed her life, transforming her from

a young enslaved woman with a small readership among friends of the Wheatley

family to an author with an international readership. The poem was published as

a broadside on October 11, 1770, and was an immediate success. It was reprinted

several times in colonial cities, as well as London, and also appeared in

several newspapers. The poem brought Wheatley to the attention of Selina, the

Countess of Huntingdon, who is addressed in the poem itself. A fervent

Methodist herself, the Countess was Whitefield's patron, supporting him on his

evangelical missions. The Countess became Wheatley's patron as well, sponsoring

the publication of her only volume of poems, published in London in 1773. The image included here shows a portrait of Whitefield by John Russel, from the National Portrait Gallery, UK.

- [JOB]wontedwonted:

"Accustomed, customary, usual." Oxford English Dictionary;

auditory: "An assembly of hearers, an audience." Oxford English

Dictionary, hence the meaning here is something like "usual audience." - [JOB]unequalled"unequalled accents"; Whitefield was a famously eloquent and compelling public

speaker; the sense here is that no other speaker could match the "accent" or style of

his voice. - [JOB]zionZion is a

name in the Hebrew bible for Jerusalem, and the term has often been extended to mean

the entirety of what believers think of as the holy land, or even the

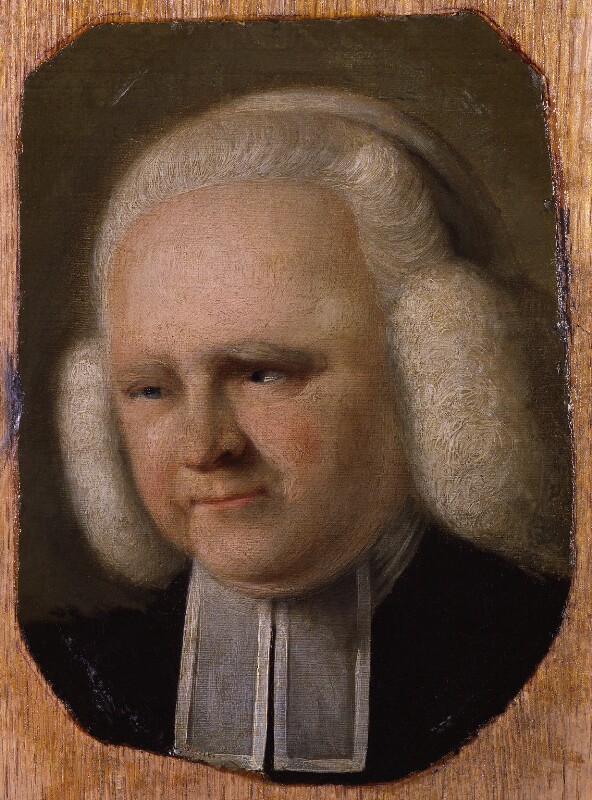

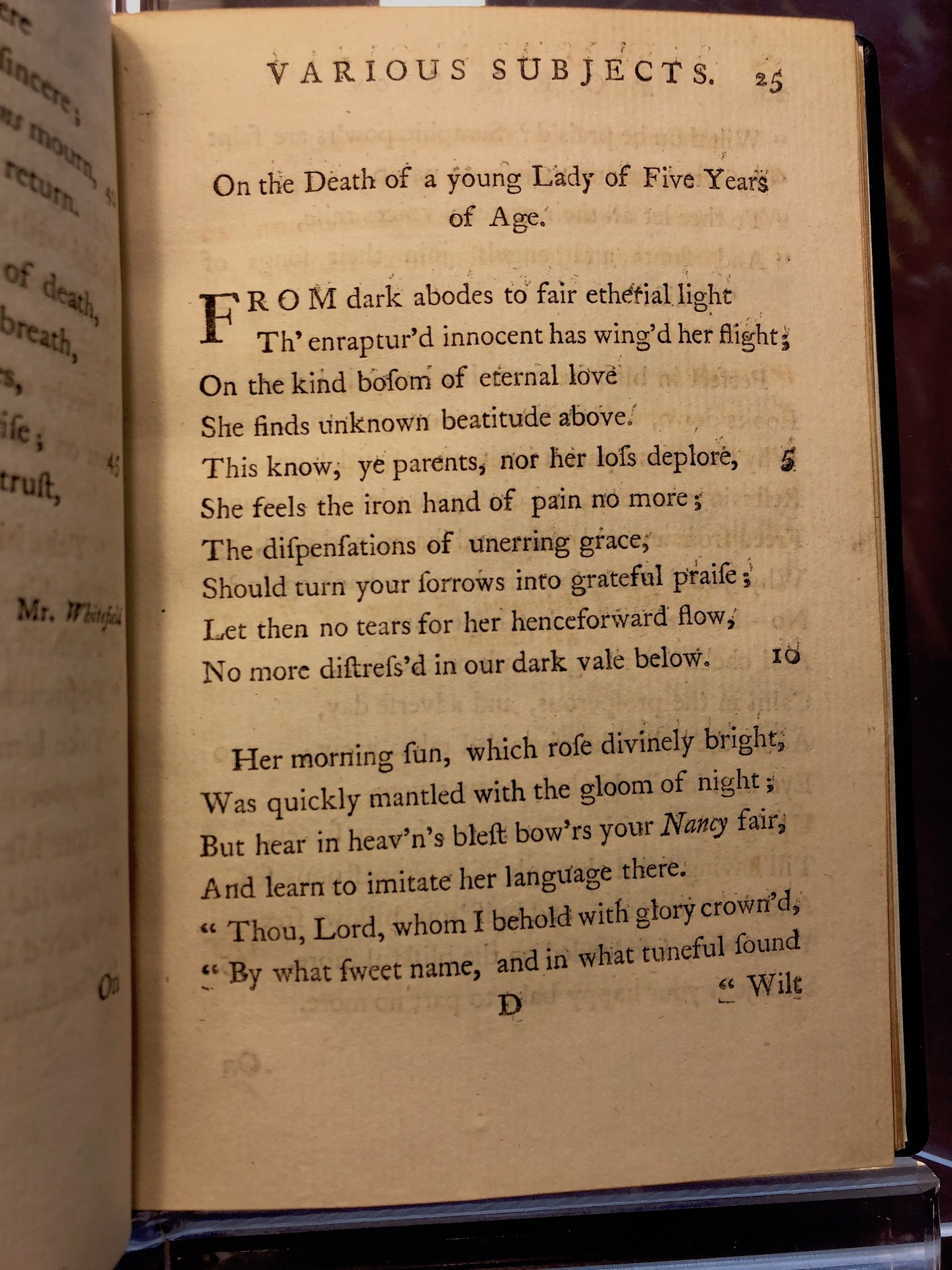

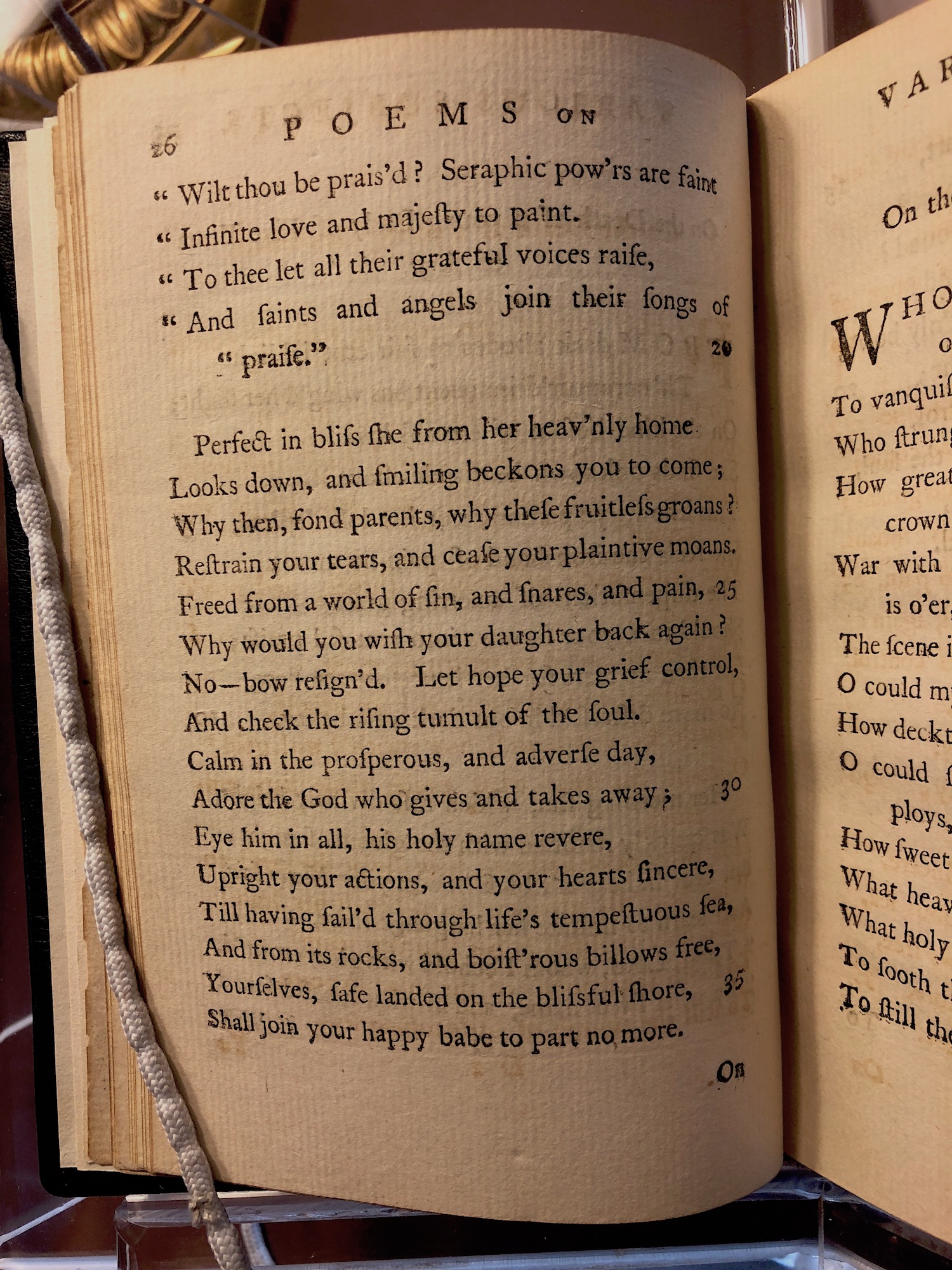

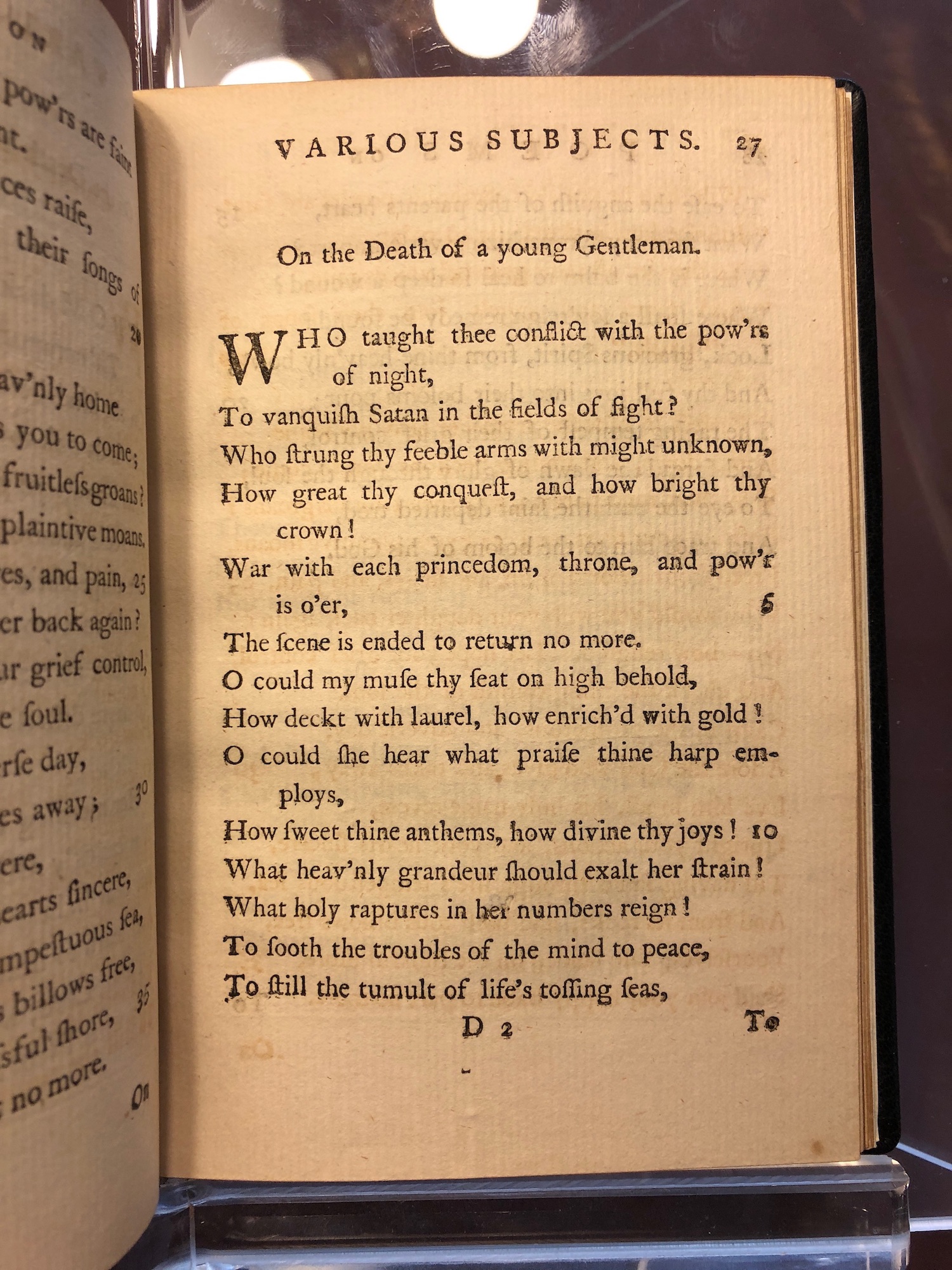

afterlife. - [JOB]countess Source: Unknown Artist, 'Portrait of Selina Hastings' (c.1770)The Countess of Huntingdon, to whom Mr. Whitefield was Chaplain.

[Wheatley's note]. Selina Hastings, the countess

of Huntingdon (1707-1791), was a major figure in the Methodist movement,

using her wealth to support the founding of chapels and a training school for

ministers. Whitefield became her personal chaplain in the 1740s. Wheatley sought and

recieved her patronage as well, and Wheatley's 1773 volume of poems was published

with her support. The image here shows a portrait of Selina Hastings by an unknown artist, about 1770, from the National

Portrait Gallery, London. - [JOB]orphansWhitefield first came to the American colonies in 1738, when he travelled to

Savannah, Georgia, where the colony's trustees had hired him to serve as minister. He

decided to make his main project in Savannah the establishment of an orphanage, and

he returned to England after only four months to raise money for the project. The

Bethesda Orphan House was founded in 1740, and Whitefield continued to raise money

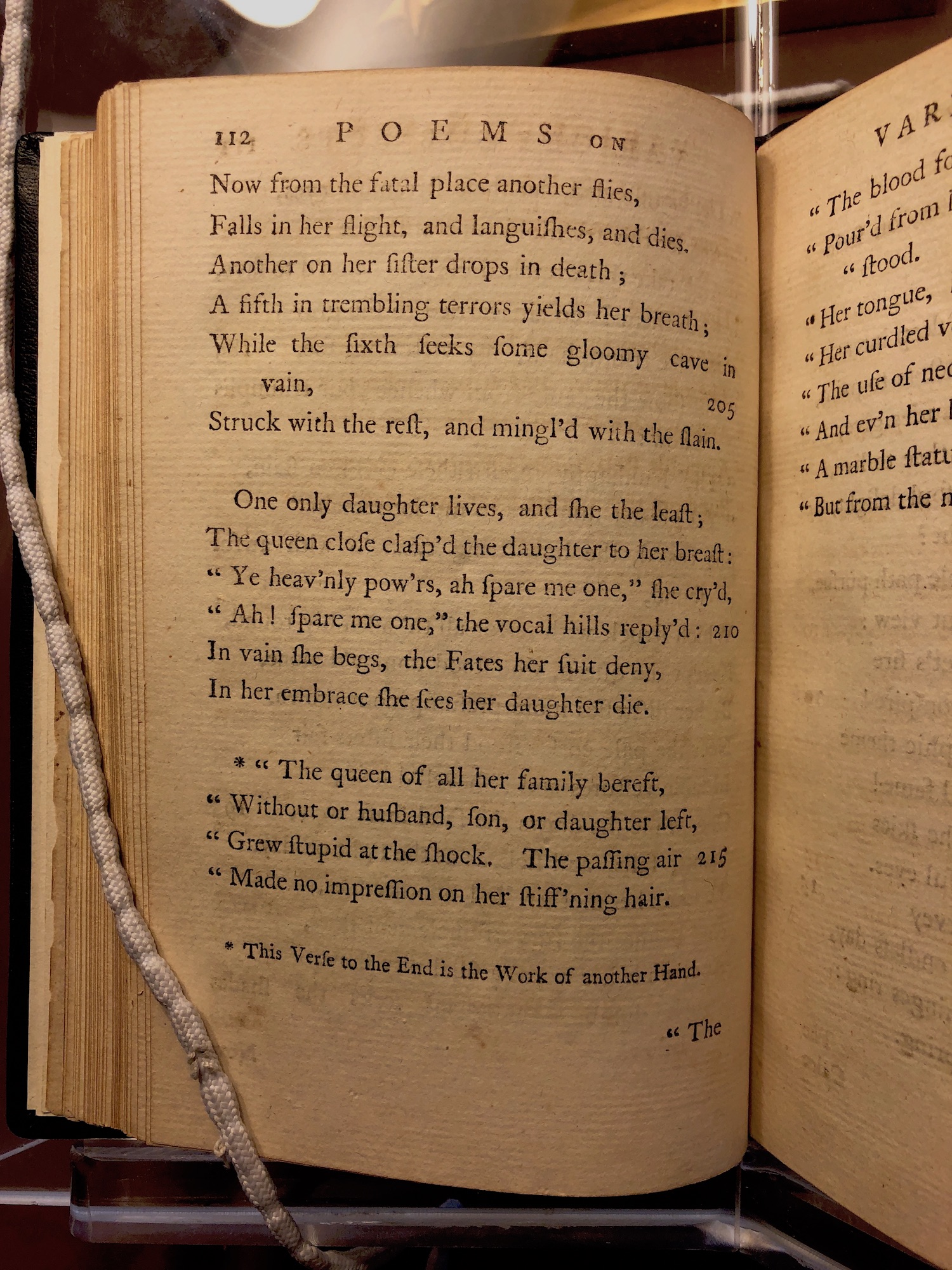

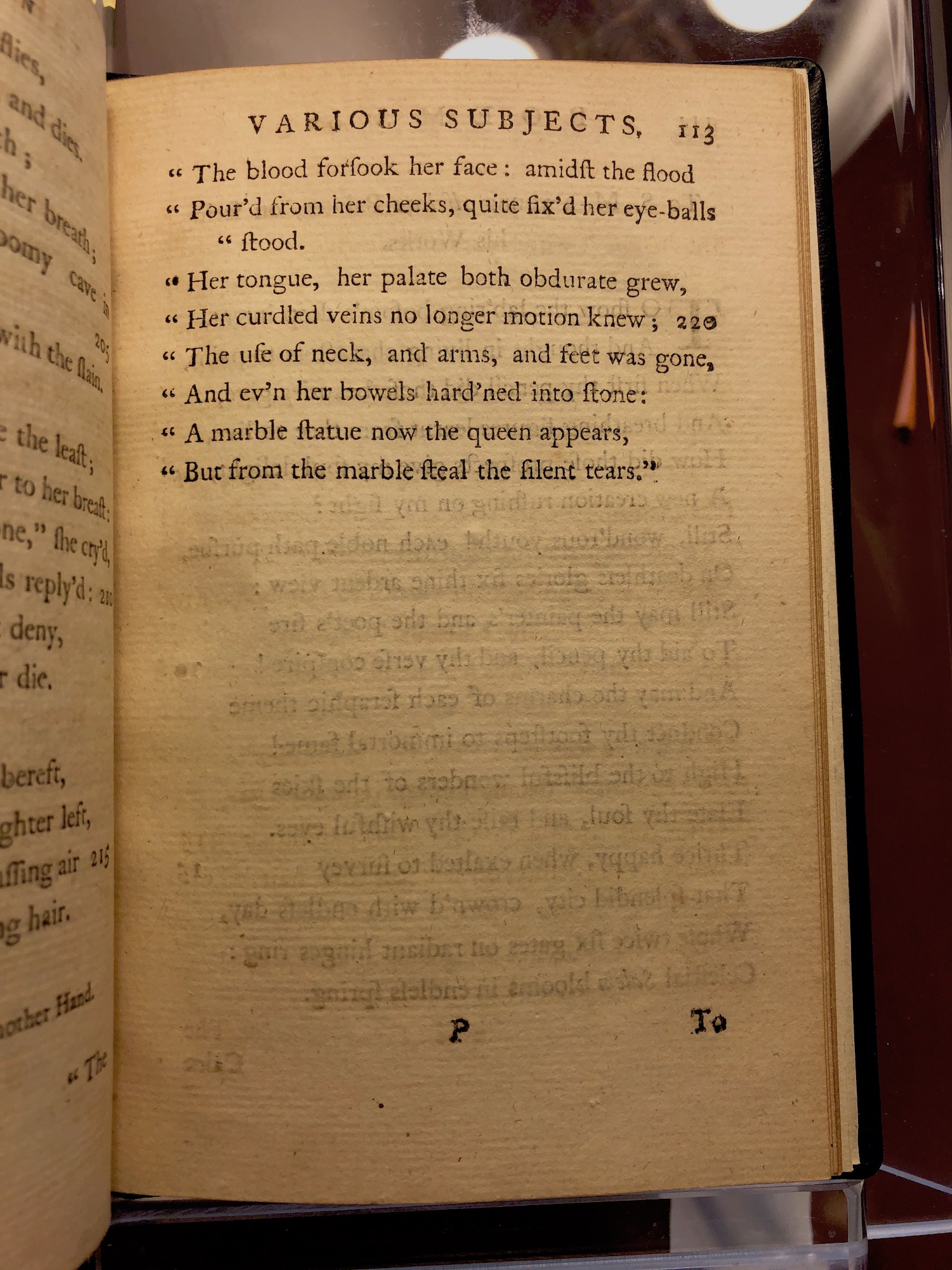

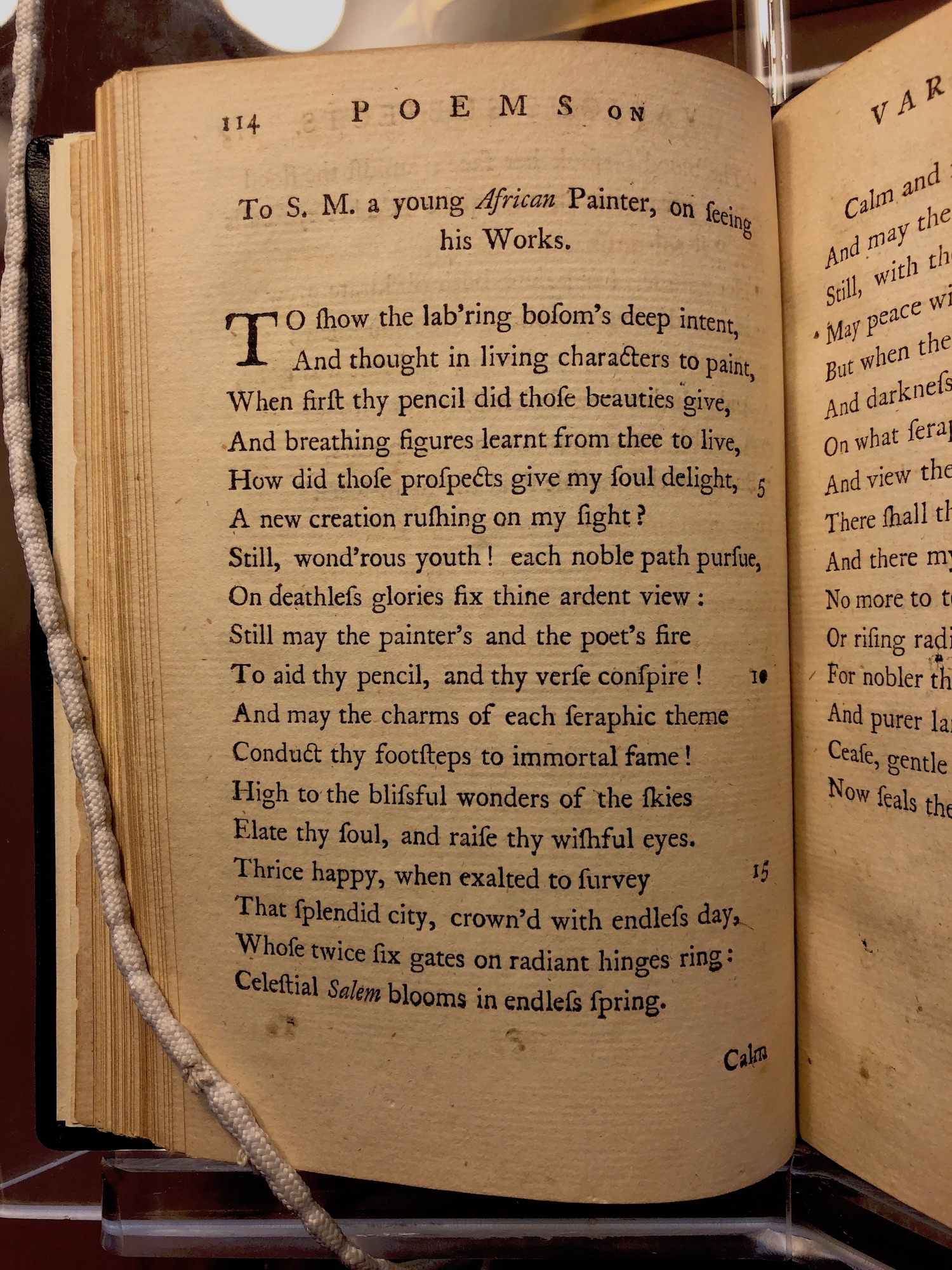

and to return for visits to the institution throughout his lifetime. - [JOB]smAccording to Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American

Experience, Scipio Moorhead was an enslaved artist, principally known

for his painting of Phillis Wheatley, which became the basis for the

frontispiece to her 1773 collection of poems. The frontispiece is included in

this database. While no signed paintings by Moorhead survive, this poem by

Wheatley may describe two of his works. Moorhead was owned by the Presbyterian

minister John Moorhead of Boston and was likely tutored by Sarah Moorhead (Appiah and Gates

62). - [TH]cityWheatley

refers to the heavenly city of "New Jerusalem," described in Revelation 21. As

many scholars have noted, Christianity offered a not uncomplicated narrative of

salvation and hope that was particularly resonant for the enslaved. She

continues this metaphor of future bliss crowning current woe throughout this

and other poems; see, for instance, lines 23-28, below. - [TH]damonDamon is a typical name for a male lover

in pastoral poetry, poetry that imagines romantic conflicts in bucolic or

country settings. Wheatley frequently both references and draws on classical

pastoral poetry throughout her Poems. For a deeper

reading of Wheatley's use of the pastoral, see John C. Shield's scholarly

essay, "Phillis Wheatley's Subversive Pastoral." - [TH]AuroraIn Greco-Roman mythology, Aurora (called

Eos in the Greek) personifies the dawn. - [TH]Three amiable Daughters who

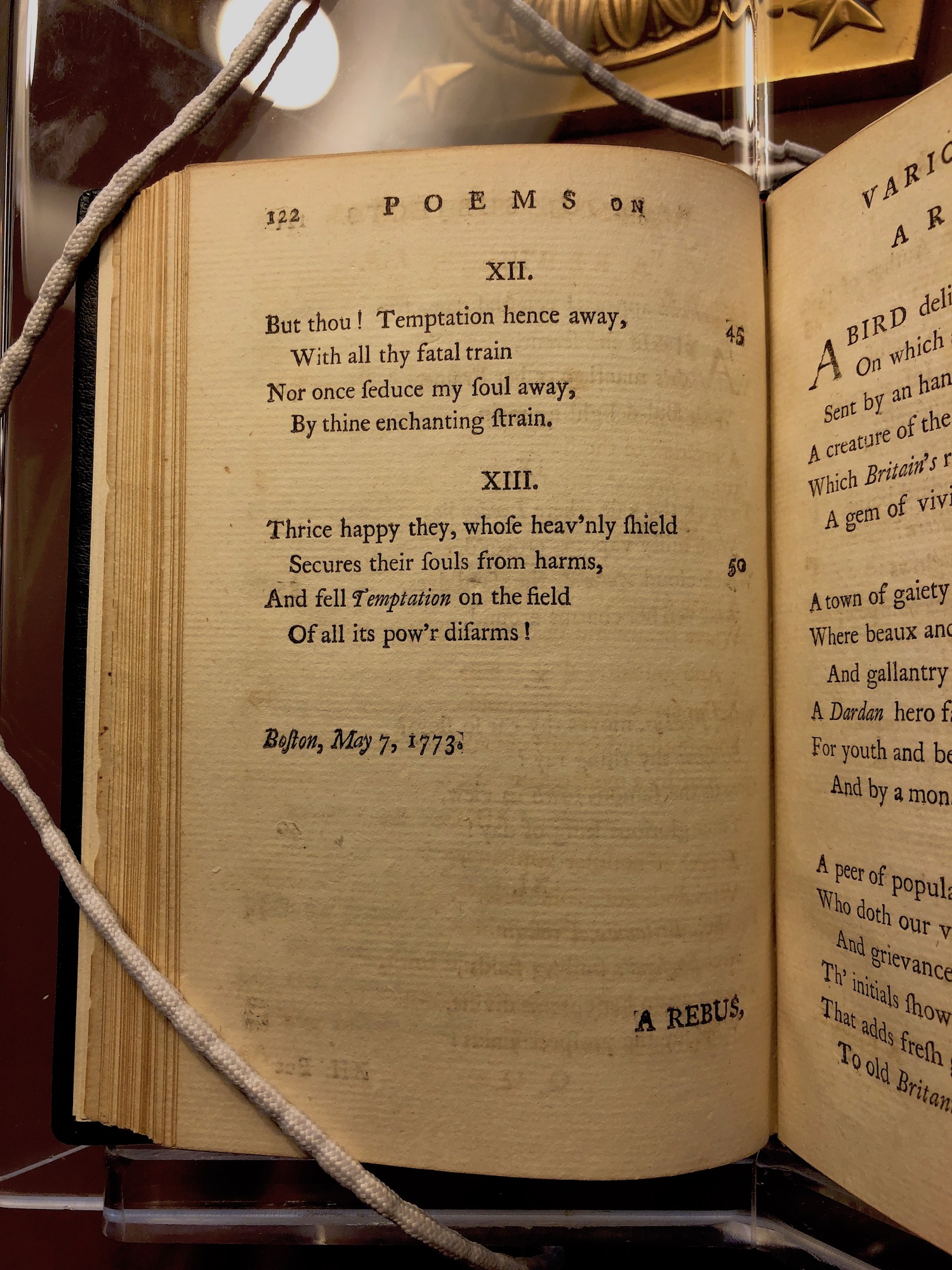

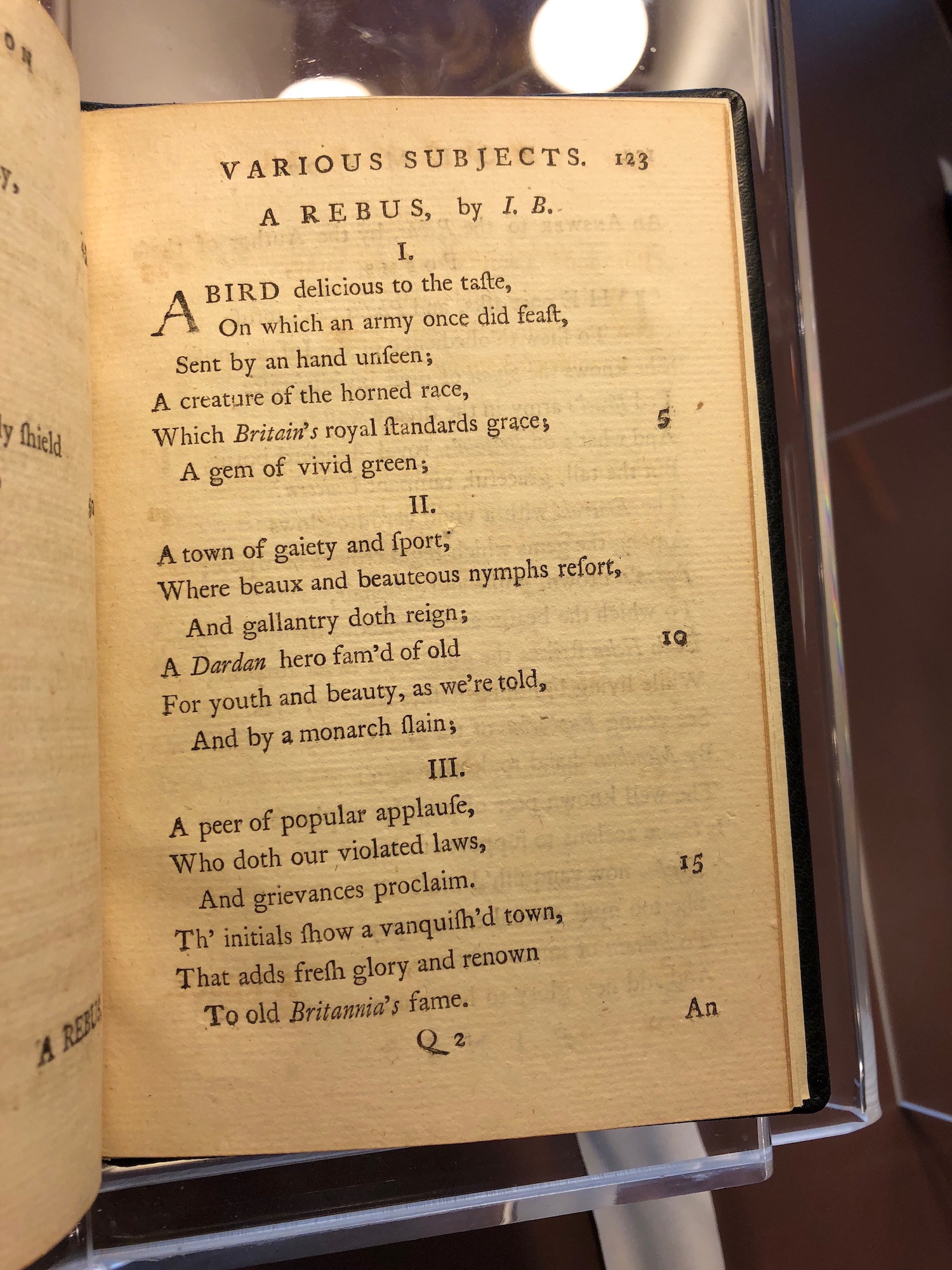

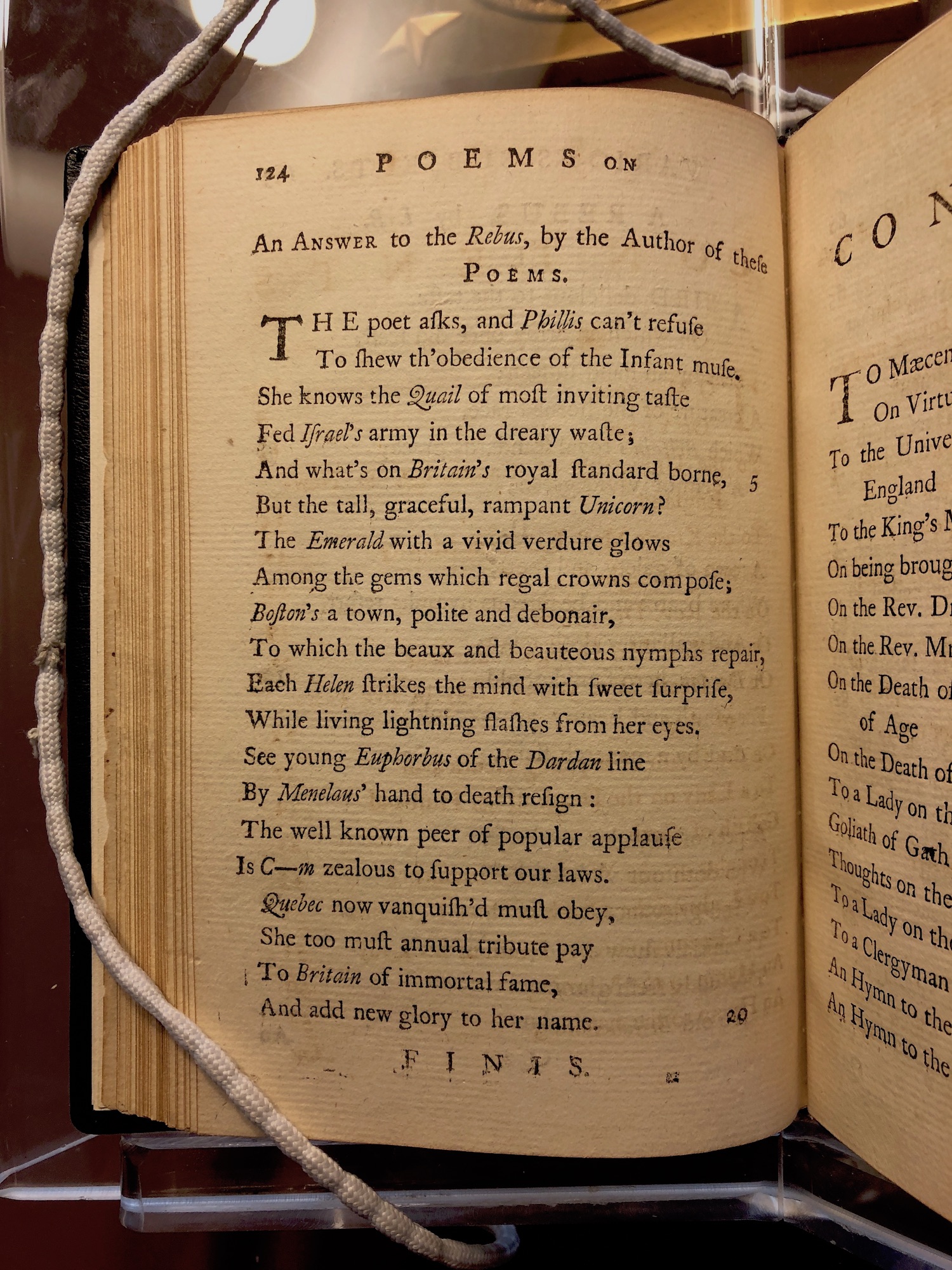

died when just arrived to Womens Estate. [Wheatley's note.]jbEditors of the Penguin edition of

Wheatley's poems reference research that identifies J. B. as James Bowdoin,

the future Governor of Massachusetts (185), depicted in this portrait from the Massachusetts

Historical Society. Bowdoin was one of the authenticators of Wheatley's

collection, his name inscribed in the front matter, as you can see in the image here,

taken from the same edition in the Library of Congress.

Source: Unknown Artist, 'Portrait of Selina Hastings' (c.1770)The Countess of Huntingdon, to whom Mr. Whitefield was Chaplain.

[Wheatley's note]. Selina Hastings, the countess

of Huntingdon (1707-1791), was a major figure in the Methodist movement,

using her wealth to support the founding of chapels and a training school for

ministers. Whitefield became her personal chaplain in the 1740s. Wheatley sought and

recieved her patronage as well, and Wheatley's 1773 volume of poems was published

with her support. The image here shows a portrait of Selina Hastings by an unknown artist, about 1770, from the National

Portrait Gallery, London. - [JOB]orphansWhitefield first came to the American colonies in 1738, when he travelled to

Savannah, Georgia, where the colony's trustees had hired him to serve as minister. He

decided to make his main project in Savannah the establishment of an orphanage, and

he returned to England after only four months to raise money for the project. The

Bethesda Orphan House was founded in 1740, and Whitefield continued to raise money

and to return for visits to the institution throughout his lifetime. - [JOB]smAccording to Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American

Experience, Scipio Moorhead was an enslaved artist, principally known

for his painting of Phillis Wheatley, which became the basis for the

frontispiece to her 1773 collection of poems. The frontispiece is included in

this database. While no signed paintings by Moorhead survive, this poem by

Wheatley may describe two of his works. Moorhead was owned by the Presbyterian

minister John Moorhead of Boston and was likely tutored by Sarah Moorhead (Appiah and Gates

62). - [TH]cityWheatley

refers to the heavenly city of "New Jerusalem," described in Revelation 21. As

many scholars have noted, Christianity offered a not uncomplicated narrative of

salvation and hope that was particularly resonant for the enslaved. She

continues this metaphor of future bliss crowning current woe throughout this

and other poems; see, for instance, lines 23-28, below. - [TH]damonDamon is a typical name for a male lover

in pastoral poetry, poetry that imagines romantic conflicts in bucolic or

country settings. Wheatley frequently both references and draws on classical

pastoral poetry throughout her Poems. For a deeper

reading of Wheatley's use of the pastoral, see John C. Shield's scholarly

essay, "Phillis Wheatley's Subversive Pastoral." - [TH]AuroraIn Greco-Roman mythology, Aurora (called

Eos in the Greek) personifies the dawn. - [TH]Three amiable Daughters who

died when just arrived to Womens Estate. [Wheatley's note.]jbEditors of the Penguin edition of

Wheatley's poems reference research that identifies J. B. as James Bowdoin,

the future Governor of Massachusetts (185), depicted in this portrait from the Massachusetts

Historical Society. Bowdoin was one of the authenticators of Wheatley's

collection, his name inscribed in the front matter, as you can see in the image here,

taken from the same edition in the Library of Congress.

Source: Oil portrait of James Bowdoin, after John Singleton Copley (19th century) - [TH]

Source: Oil portrait of James Bowdoin, after John Singleton Copley (19th century) - [TH]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samson_Occom

- [MUStudStaff]maecenas

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samson_Occom

- [MUStudStaff]maecenas Source: Gavin Hamilton, 'Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus' (1760-1763)Achilles is the main character of The Illiad, which tells the story of the Trojan War and,

specifically, Achilles' wrath. Achilles and Patroclus are lovers and friends;

angered by Agammemnon, Achilles refuses to fight, but allows Patroclus to wear

his armor and lead the Myrmidons against the Trojans. When Patroclus is killed

by Hector, Achilles is grief-stricken and, enraged, he returns to battle to

destroy the Trojans. The image included here, Gavin Hamilton's Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus (1760-1763), is

housed in National Galleries, Scotland. - [TH]pelidesPelides is Achilles' father; therefore, it is also

another way of referring to Achilles himself. Achilles is frequently described

as "stern" by Homer. - [TH]maroPublius Vergilius Maro, more commonly known as Virgil,

the Augustan Roman poet famed for his Eclogues and the epic poem The Aeneid. - [TH]nineThe nine muses in Greco-Roman mythology are goddesses,

daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne who inspire those in the arts and

sciences. - [TH]mantuaMantua

is a city in Italy, and the home of Virgil; the Mantuan sage is the poet

Virgil. - [TH]fainMeaning "[g]ladly,

willingly, with pleasure," according to the OED (fain, adv.B). - [TH]heliconMount Helicon in Greece is a mountain

believed to be the home of the muses and hence a place sacred to poetry. - [TH]falteringAn alternate spelling and contraction, for meter, of "faltering," meaning

unsteady or staggering. - [TH]terencePublius Terentius Afer, better known as

Terence, is a famous Roman comic playwright, born in northern Africa. As the

Encylopedia Britannicanotes, Terence was enslaved and later

freed by a Roman senator. Wheatley suggests a connection between herself and

Terence, both of African origin; yet, Terence is "happier"--both in his poetic

skill, and perhaps also in having been freed. - [TH]laurel

Source: Gavin Hamilton, 'Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus' (1760-1763)Achilles is the main character of The Illiad, which tells the story of the Trojan War and,

specifically, Achilles' wrath. Achilles and Patroclus are lovers and friends;

angered by Agammemnon, Achilles refuses to fight, but allows Patroclus to wear

his armor and lead the Myrmidons against the Trojans. When Patroclus is killed

by Hector, Achilles is grief-stricken and, enraged, he returns to battle to

destroy the Trojans. The image included here, Gavin Hamilton's Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus (1760-1763), is

housed in National Galleries, Scotland. - [TH]pelidesPelides is Achilles' father; therefore, it is also

another way of referring to Achilles himself. Achilles is frequently described

as "stern" by Homer. - [TH]maroPublius Vergilius Maro, more commonly known as Virgil,

the Augustan Roman poet famed for his Eclogues and the epic poem The Aeneid. - [TH]nineThe nine muses in Greco-Roman mythology are goddesses,

daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne who inspire those in the arts and

sciences. - [TH]mantuaMantua

is a city in Italy, and the home of Virgil; the Mantuan sage is the poet

Virgil. - [TH]fainMeaning "[g]ladly,

willingly, with pleasure," according to the OED (fain, adv.B). - [TH]heliconMount Helicon in Greece is a mountain

believed to be the home of the muses and hence a place sacred to poetry. - [TH]falteringAn alternate spelling and contraction, for meter, of "faltering," meaning

unsteady or staggering. - [TH]terencePublius Terentius Afer, better known as

Terence, is a famous Roman comic playwright, born in northern Africa. As the

Encylopedia Britannicanotes, Terence was enslaved and later

freed by a Roman senator. Wheatley suggests a connection between herself and

Terence, both of African origin; yet, Terence is "happier"--both in his poetic

skill, and perhaps also in having been freed. - [TH]laurel Source: Jonathan Richardson, 'Portrait of Alexander Pope' (1737)The leaves of the bay laurel tree were a

conventional symbol of poetic fame and acheivement originating in the

mythological tale of Daphne and

Apollo. The image included here is a portrait of the 18th century poet

Alexander Pope, wearing a crown of laurel. The portrait (c.1737), by Jonathan

Richardson, is housed in the National

Portrait Gallery, London. - [TH]thamesThe Thames is a major river flowing

through southern England and London. - [TH]naiads

Source: Jonathan Richardson, 'Portrait of Alexander Pope' (1737)The leaves of the bay laurel tree were a

conventional symbol of poetic fame and acheivement originating in the

mythological tale of Daphne and

Apollo. The image included here is a portrait of the 18th century poet

Alexander Pope, wearing a crown of laurel. The portrait (c.1737), by Jonathan

Richardson, is housed in the National

Portrait Gallery, London. - [TH]thamesThe Thames is a major river flowing

through southern England and London. - [TH]naiads Source: Jean-Francois de Troy, 'Pan and Syrinx' (1722-1724)In Greco-Roman

mythology, naiads are female freshwater nymphs. The image included here, by

Jean-Francois de Troy, shows part of the Ovidian story of Pan and Syrinx

(1722-1724). De Troy's Pan and Syrinx is housed in the

Getty Museum. - [TH]phoebusPhoebus Apollo is an important god in the Greco-Roman

tradition. He is associated with both the sun and with music and poetry. - [TH]auroraIn Greco-Roman mythology, Aurora (called Eos in the

Greek) personifies the dawn. - [TH]parnassusParnassus is a

mountain in Greece that was seen as the home of the gods, particularly Dionysus

and Apollo, as well as the Muses. The Muses are also associated with Mount

Helicon. - [TH]cambridge

Source: Jean-Francois de Troy, 'Pan and Syrinx' (1722-1724)In Greco-Roman

mythology, naiads are female freshwater nymphs. The image included here, by

Jean-Francois de Troy, shows part of the Ovidian story of Pan and Syrinx

(1722-1724). De Troy's Pan and Syrinx is housed in the

Getty Museum. - [TH]phoebusPhoebus Apollo is an important god in the Greco-Roman

tradition. He is associated with both the sun and with music and poetry. - [TH]auroraIn Greco-Roman mythology, Aurora (called Eos in the

Greek) personifies the dawn. - [TH]parnassusParnassus is a

mountain in Greece that was seen as the home of the gods, particularly Dionysus

and Apollo, as well as the Muses. The Muses are also associated with Mount

Helicon. - [TH]cambridge

Source: Paul Revere, 'A Westerley View of the Colledges in Cambridge, New England' (1767)After describing her own educational journey, Wheatley

advises students at the University of Cambridge in New England to appreciate

and "[i]mprove" (21) the privilege of their education by "shunn[ing]" (25) the

"transient sweetness" (29) of sin using a variety of religious images. The

University of Cambridge in New England is now known as Harvard University. According to

Katherine Clay Bassard, Wheatley wrote this poem when she was about

fourteen years old (41). The engraving included here is by Paul Revere and

shows "A Westerly View of The Colledges in Cambridge New England" (1767), via

NYPL Digital Collections. - [JW]ardorWheatley works from the premise, commonly used among early women writers

and the enslaved who were restricted from intellectual pursuits like

writing, that her desire to write is "intrinsic" (1) or God-given, and

therefore appropriate. The word "ardor" also connotes physical desire and

flame-like passion, according to the OED (n.3). - [JW]musesAccording to A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology, the Muses are “inspiring goddesses of song" who

“presid[e] over the different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and

sciences." The “invocation of the muse” to aid the poet's work is often used

by neoclassical authors like those whom Wheatley has clearly read and was

influenced by, including Milton and Pope.

However, Hilene Flanzbaum suggests that Wheatley’s notably frequent

invocation of the muse is more significant than formulaic or imitative--it

is “the very means by which she usurps power for herself and claims a berth

for her own thoughts, emotions and desires. And while some may claim that

these functions accompany any appearance of the muse, when the muses bestow

their power on a black female slave, they transport Wheatley to a domain

surprisingly free of restriction and previously forbidden” (“Unprecedented Liberties”

75). - [JW]egyptianWheatley here

alludes to Exodus

10:21-22, wherein the ninth plague of darkness is visited upon

Egypt. This reference is also in line with contemporary Orientalist notions

about Egypt and Egyptian religiosity, which was believed to be full of

occult practices. Early nineteenth-century British historian and scholar

Thomas Maurice explores these ideas of idolatry and superstition in Observations on

the Remains of Ancient Egyptian Grandeur and Superstition. A

detailed focus on the Egyptian religious practices can be found in the

chapter "Strictures on the superstitious rites of the Egyptians,

particularly on the Nefarious Worship paid to Beasts, Esteemed Sacred, and

called in Scripture the Abominations of Egypt" (74-83). - [JW]systems

Source: Paul Revere, 'A Westerley View of the Colledges in Cambridge, New England' (1767)After describing her own educational journey, Wheatley

advises students at the University of Cambridge in New England to appreciate

and "[i]mprove" (21) the privilege of their education by "shunn[ing]" (25) the

"transient sweetness" (29) of sin using a variety of religious images. The

University of Cambridge in New England is now known as Harvard University. According to

Katherine Clay Bassard, Wheatley wrote this poem when she was about

fourteen years old (41). The engraving included here is by Paul Revere and

shows "A Westerly View of The Colledges in Cambridge New England" (1767), via

NYPL Digital Collections. - [JW]ardorWheatley works from the premise, commonly used among early women writers

and the enslaved who were restricted from intellectual pursuits like

writing, that her desire to write is "intrinsic" (1) or God-given, and

therefore appropriate. The word "ardor" also connotes physical desire and

flame-like passion, according to the OED (n.3). - [JW]musesAccording to A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology, the Muses are “inspiring goddesses of song" who

“presid[e] over the different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and

sciences." The “invocation of the muse” to aid the poet's work is often used

by neoclassical authors like those whom Wheatley has clearly read and was

influenced by, including Milton and Pope.

However, Hilene Flanzbaum suggests that Wheatley’s notably frequent

invocation of the muse is more significant than formulaic or imitative--it

is “the very means by which she usurps power for herself and claims a berth

for her own thoughts, emotions and desires. And while some may claim that

these functions accompany any appearance of the muse, when the muses bestow

their power on a black female slave, they transport Wheatley to a domain

surprisingly free of restriction and previously forbidden” (“Unprecedented Liberties”

75). - [JW]egyptianWheatley here

alludes to Exodus

10:21-22, wherein the ninth plague of darkness is visited upon

Egypt. This reference is also in line with contemporary Orientalist notions

about Egypt and Egyptian religiosity, which was believed to be full of

occult practices. Early nineteenth-century British historian and scholar

Thomas Maurice explores these ideas of idolatry and superstition in Observations on

the Remains of Ancient Egyptian Grandeur and Superstition. A

detailed focus on the Egyptian religious practices can be found in the

chapter "Strictures on the superstitious rites of the Egyptians,

particularly on the Nefarious Worship paid to Beasts, Esteemed Sacred, and

called in Scripture the Abominations of Egypt" (74-83). - [JW]systems Source: Joseph Wright, 'Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery' (1766)The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

development of the microscope and the telescope had made great scientific

advancements possible, especially in astronomy; in the painting by Joseph

Wright here, you can see an eighteenth-century orrery--a scientific

clockwork instrument used to dramatize the motion of the planets in the

solar system (via Wikimedia Commons). Possibly an allusion to Alexander

Pope's 1733-34 Essay on Man (I.23-28), Wheatley here may

also be referencing contemporary scientific thought about the plurality of worlds. - [JW]deign According to the

Oxford English Dictionary deign means "to think it worthy of oneself" or "to think fit"

(n.1a). Today, it typically has a negative connotation, though it does not

here. - [JW]ethiop

Source: Joseph Wright, 'Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery' (1766)The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

development of the microscope and the telescope had made great scientific

advancements possible, especially in astronomy; in the painting by Joseph

Wright here, you can see an eighteenth-century orrery--a scientific

clockwork instrument used to dramatize the motion of the planets in the

solar system (via Wikimedia Commons). Possibly an allusion to Alexander

Pope's 1733-34 Essay on Man (I.23-28), Wheatley here may

also be referencing contemporary scientific thought about the plurality of worlds. - [JW]deign According to the

Oxford English Dictionary deign means "to think it worthy of oneself" or "to think fit"

(n.1a). Today, it typically has a negative connotation, though it does not

here. - [JW]ethiop

Source: John Overton, 'A new and most exact map of Africa' (1666)According

to the OED, the word Ethiop would

have been used during Wheatley's time most often to refer to "[a] black or

dark-skinned person; a black African," and only occasionally to the country

of Ethiopia, specifically (n.A). Included here, via the Norwich Collection at Stanford University, is a 1666 map

of Africa and the surrounding oceans, embellished with a variety of images.

- [JW]perditionIn theological discussion, the word perdition means "the

state of final spiritual ruin or damnation; the consignment of the

unredeemed or wicked and impenitent soul to hell; the fate of those in hell;

eternal death" (OED, "perdition" n.2a). In more general terms, it suggests

ruin or degradation (n.1a). - [JW]brought

Source: John Overton, 'A new and most exact map of Africa' (1666)According

to the OED, the word Ethiop would

have been used during Wheatley's time most often to refer to "[a] black or

dark-skinned person; a black African," and only occasionally to the country

of Ethiopia, specifically (n.A). Included here, via the Norwich Collection at Stanford University, is a 1666 map

of Africa and the surrounding oceans, embellished with a variety of images.

- [JW]perditionIn theological discussion, the word perdition means "the

state of final spiritual ruin or damnation; the consignment of the

unredeemed or wicked and impenitent soul to hell; the fate of those in hell;

eternal death" (OED, "perdition" n.2a). In more general terms, it suggests

ruin or degradation (n.1a). - [JW]brought The title of one Wheatley's most (in)famous poems, "On being brought from

AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the experiences of many Africans who became

subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801). - [JW]viewWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

- [TH]cainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)

- [JW]whitfield

The title of one Wheatley's most (in)famous poems, "On being brought from

AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the experiences of many Africans who became

subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801). - [JW]viewWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

- [TH]cainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)

- [JW]whitfield

Source: John Russell, 'Portrait of George Whitefield' (c.1770)

George Whitefield (1714-1770; pronounced "wit-field") was one of the most

famous people of the eighteenth-century Anglophone world. As a student at

Oxford in the early 1730s, he got to know John and Charles Wesley, the founders

of the Methodist movement in the church of England. Whitefield joined them in

attempting to "methodize" the faith, returning it to the simple principles of

the early church. But more than the Wesley brothers, Whitefield made this

reformist movement into a public ministry. A famously charismatic public

speaker, Whitefield preached to crowds numbering in the thousands in England

and the American colonies, becoming a central figure in what was known as the

"Great Awakening," a revival of evangelical Protestantism that was influential

on both sides of the Atlantic. Benjamin Franklin and Olaudah Equiano were each

impressed (though in very different ways) when they saw Whitefield preach in

Philadelphia and Savannah, respectively. Whitefield made several visits to the

Boston area, and it seems likely that the Wheatleys saw him preach there.

Phillis might very well have joined them, but we cannot be sure. Whitefield

died unexpectedly in Newburyport, Massachusetts on September 30, 1770, a few

days after he left Boston on what turned out to be his last tour of the

colonies.

Phillis Wheatley's elegy for Whitefield changed her life, transforming her from

a young enslaved woman with a small readership among friends of the Wheatley

family to an author with an international readership. The poem was published as

a broadside on October 11, 1770, and was an immediate success. It was reprinted

several times in colonial cities, as well as London, and also appeared in

several newspapers. The poem brought Wheatley to the attention of Selina, the

Countess of Huntingdon, who is addressed in the poem itself. A fervent

Methodist herself, the Countess was Whitefield's patron, supporting him on his

evangelical missions. The Countess became Wheatley's patron as well, sponsoring

the publication of her only volume of poems, published in London in 1773. The image included here shows a portrait of Whitefield by John Russel, from the National Portrait Gallery, UK.

- [JOB]wontedwonted:

"Accustomed, customary, usual." Oxford English Dictionary;

auditory: "An assembly of hearers, an audience." Oxford English

Dictionary, hence the meaning here is something like "usual audience." - [JOB]unequalled"unequalled accents"; Whitefield was a famously eloquent and compelling public

speaker; the sense here is that no other speaker could match the "accent" or style of

his voice. - [JOB]zionZion is a

name in the Hebrew bible for Jerusalem, and the term has often been extended to mean

the entirety of what believers think of as the holy land, or even the

afterlife. - [JOB]countess

Source: John Russell, 'Portrait of George Whitefield' (c.1770)

George Whitefield (1714-1770; pronounced "wit-field") was one of the most

famous people of the eighteenth-century Anglophone world. As a student at

Oxford in the early 1730s, he got to know John and Charles Wesley, the founders

of the Methodist movement in the church of England. Whitefield joined them in

attempting to "methodize" the faith, returning it to the simple principles of

the early church. But more than the Wesley brothers, Whitefield made this

reformist movement into a public ministry. A famously charismatic public

speaker, Whitefield preached to crowds numbering in the thousands in England

and the American colonies, becoming a central figure in what was known as the

"Great Awakening," a revival of evangelical Protestantism that was influential

on both sides of the Atlantic. Benjamin Franklin and Olaudah Equiano were each

impressed (though in very different ways) when they saw Whitefield preach in

Philadelphia and Savannah, respectively. Whitefield made several visits to the

Boston area, and it seems likely that the Wheatleys saw him preach there.

Phillis might very well have joined them, but we cannot be sure. Whitefield

died unexpectedly in Newburyport, Massachusetts on September 30, 1770, a few

days after he left Boston on what turned out to be his last tour of the

colonies.

Phillis Wheatley's elegy for Whitefield changed her life, transforming her from

a young enslaved woman with a small readership among friends of the Wheatley

family to an author with an international readership. The poem was published as

a broadside on October 11, 1770, and was an immediate success. It was reprinted

several times in colonial cities, as well as London, and also appeared in

several newspapers. The poem brought Wheatley to the attention of Selina, the

Countess of Huntingdon, who is addressed in the poem itself. A fervent

Methodist herself, the Countess was Whitefield's patron, supporting him on his

evangelical missions. The Countess became Wheatley's patron as well, sponsoring

the publication of her only volume of poems, published in London in 1773. The image included here shows a portrait of Whitefield by John Russel, from the National Portrait Gallery, UK.

- [JOB]wontedwonted:

"Accustomed, customary, usual." Oxford English Dictionary;

auditory: "An assembly of hearers, an audience." Oxford English

Dictionary, hence the meaning here is something like "usual audience." - [JOB]unequalled"unequalled accents"; Whitefield was a famously eloquent and compelling public

speaker; the sense here is that no other speaker could match the "accent" or style of

his voice. - [JOB]zionZion is a

name in the Hebrew bible for Jerusalem, and the term has often been extended to mean

the entirety of what believers think of as the holy land, or even the

afterlife. - [JOB]countess Source: Unknown Artist, 'Portrait of Selina Hastings' (c.1770)The Countess of Huntingdon, to whom Mr. Whitefield was Chaplain.

[Wheatley's note]. Selina Hastings, the countess

of Huntingdon (1707-1791), was a major figure in the Methodist movement,

using her wealth to support the founding of chapels and a training school for

ministers. Whitefield became her personal chaplain in the 1740s. Wheatley sought and

recieved her patronage as well, and Wheatley's 1773 volume of poems was published

with her support. The image here shows a portrait of Selina Hastings by an unknown artist, about 1770, from the National

Portrait Gallery, London. - [JOB]orphansWhitefield first came to the American colonies in 1738, when he travelled to

Savannah, Georgia, where the colony's trustees had hired him to serve as minister. He

decided to make his main project in Savannah the establishment of an orphanage, and

he returned to England after only four months to raise money for the project. The

Bethesda Orphan House was founded in 1740, and Whitefield continued to raise money

and to return for visits to the institution throughout his lifetime. - [JOB]smAccording to Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American

Experience, Scipio Moorhead was an enslaved artist, principally known

for his painting of Phillis Wheatley, which became the basis for the

frontispiece to her 1773 collection of poems. The frontispiece is included in

this database. While no signed paintings by Moorhead survive, this poem by

Wheatley may describe two of his works. Moorhead was owned by the Presbyterian

minister John Moorhead of Boston and was likely tutored by Sarah Moorhead (Appiah and Gates

62). - [TH]cityWheatley

refers to the heavenly city of "New Jerusalem," described in Revelation 21. As

many scholars have noted, Christianity offered a not uncomplicated narrative of

salvation and hope that was particularly resonant for the enslaved. She

continues this metaphor of future bliss crowning current woe throughout this

and other poems; see, for instance, lines 23-28, below. - [TH]damonDamon is a typical name for a male lover

in pastoral poetry, poetry that imagines romantic conflicts in bucolic or

country settings. Wheatley frequently both references and draws on classical

pastoral poetry throughout her Poems. For a deeper

reading of Wheatley's use of the pastoral, see John C. Shield's scholarly

essay, "Phillis Wheatley's Subversive Pastoral." - [TH]AuroraIn Greco-Roman mythology, Aurora (called

Eos in the Greek) personifies the dawn. - [TH]Three amiable Daughters who

died when just arrived to Womens Estate. [Wheatley's note.]jbEditors of the Penguin edition of

Wheatley's poems reference research that identifies J. B. as James Bowdoin,

the future Governor of Massachusetts (185), depicted in this portrait from the Massachusetts

Historical Society. Bowdoin was one of the authenticators of Wheatley's

collection, his name inscribed in the front matter, as you can see in the image here,

taken from the same edition in the Library of Congress.

Source: Unknown Artist, 'Portrait of Selina Hastings' (c.1770)The Countess of Huntingdon, to whom Mr. Whitefield was Chaplain.

[Wheatley's note]. Selina Hastings, the countess

of Huntingdon (1707-1791), was a major figure in the Methodist movement,

using her wealth to support the founding of chapels and a training school for

ministers. Whitefield became her personal chaplain in the 1740s. Wheatley sought and

recieved her patronage as well, and Wheatley's 1773 volume of poems was published

with her support. The image here shows a portrait of Selina Hastings by an unknown artist, about 1770, from the National

Portrait Gallery, London. - [JOB]orphansWhitefield first came to the American colonies in 1738, when he travelled to

Savannah, Georgia, where the colony's trustees had hired him to serve as minister. He

decided to make his main project in Savannah the establishment of an orphanage, and

he returned to England after only four months to raise money for the project. The

Bethesda Orphan House was founded in 1740, and Whitefield continued to raise money

and to return for visits to the institution throughout his lifetime. - [JOB]smAccording to Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American

Experience, Scipio Moorhead was an enslaved artist, principally known

for his painting of Phillis Wheatley, which became the basis for the

frontispiece to her 1773 collection of poems. The frontispiece is included in

this database. While no signed paintings by Moorhead survive, this poem by

Wheatley may describe two of his works. Moorhead was owned by the Presbyterian

minister John Moorhead of Boston and was likely tutored by Sarah Moorhead (Appiah and Gates

62). - [TH]cityWheatley

refers to the heavenly city of "New Jerusalem," described in Revelation 21. As

many scholars have noted, Christianity offered a not uncomplicated narrative of

salvation and hope that was particularly resonant for the enslaved. She

continues this metaphor of future bliss crowning current woe throughout this

and other poems; see, for instance, lines 23-28, below. - [TH]damonDamon is a typical name for a male lover

in pastoral poetry, poetry that imagines romantic conflicts in bucolic or

country settings. Wheatley frequently both references and draws on classical

pastoral poetry throughout her Poems. For a deeper

reading of Wheatley's use of the pastoral, see John C. Shield's scholarly

essay, "Phillis Wheatley's Subversive Pastoral." - [TH]AuroraIn Greco-Roman mythology, Aurora (called

Eos in the Greek) personifies the dawn. - [TH]Three amiable Daughters who

died when just arrived to Womens Estate. [Wheatley's note.]jbEditors of the Penguin edition of

Wheatley's poems reference research that identifies J. B. as James Bowdoin,

the future Governor of Massachusetts (185), depicted in this portrait from the Massachusetts

Historical Society. Bowdoin was one of the authenticators of Wheatley's

collection, his name inscribed in the front matter, as you can see in the image here,

taken from the same edition in the Library of Congress.  Source: Oil portrait of James Bowdoin, after John Singleton Copley (19th century) - [TH]

Source: Oil portrait of James Bowdoin, after John Singleton Copley (19th century) - [TH]Footnotes

occom_In Wheatley's letter to Samson Occom, she affirms

his "Vindication of their [the enslaved] natural Rights." She concludes with an

ellipsis in which she implicitly criticizes the "strange Absurdity" of Christian

slavers. To read the letter in its entirety, visit American Literature I. Samson Occom

(1723-1792), a Native American member of the Mohegan Nation, was an author,

teacher, judge, and Presbyterian minister. The image here, via Wikimedia Commons,

is a mezzotint portrait of the Reverend Occom from 1768. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samson_Occom

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samson_Occom

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samson_Occom

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samson_Occom

maecenas_ Source: Wheatley's 'Attestation to the Public'Maecenas was the wealthy patron of classical

Roman poets Virgil and Horace, whom Wheatley draws on in complex ways.

Wheatley's poem "To Maecenas" opens her collection, which position gives it a

powerful significance as she claims the right to speak within this tradition.

Like Horace's Odes to Maecenas, Wheatley's offers praise to her patron,

but does so in ways that are fraught with the equivocalities of being an

enslaved African working within the languge and culture of the colonial master.

For a deeper reading of "To Maecenas," see Paula Bennett's journal article,

"Phillis Wheatley's Vocation and the Paradox of the 'Afric Muse.'" Following

other scholars, Bennett identifies Wheatley's poet-patron as Mather Byles, one

of the signatories verifying her authorship. The image included here shows the

attestation to the public, included in the 1773 edition of Wheatley's poems,

certifying that they were indeed written by "PHILLIS, a young Negro Girl, who

was but a few Years since, brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa,...and now is, under the Disadvantage of serving

as a Slave in a Family in [Boston]." Note Bales' name.

Source: Wheatley's 'Attestation to the Public'Maecenas was the wealthy patron of classical

Roman poets Virgil and Horace, whom Wheatley draws on in complex ways.

Wheatley's poem "To Maecenas" opens her collection, which position gives it a

powerful significance as she claims the right to speak within this tradition.

Like Horace's Odes to Maecenas, Wheatley's offers praise to her patron,

but does so in ways that are fraught with the equivocalities of being an

enslaved African working within the languge and culture of the colonial master.

For a deeper reading of "To Maecenas," see Paula Bennett's journal article,

"Phillis Wheatley's Vocation and the Paradox of the 'Afric Muse.'" Following

other scholars, Bennett identifies Wheatley's poet-patron as Mather Byles, one

of the signatories verifying her authorship. The image included here shows the

attestation to the public, included in the 1773 edition of Wheatley's poems,

certifying that they were indeed written by "PHILLIS, a young Negro Girl, who

was but a few Years since, brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa,...and now is, under the Disadvantage of serving

as a Slave in a Family in [Boston]." Note Bales' name.

homer_Homer is the ancient Greek poet of The

Oddyssey and The Illiad.

achilles_ Source: Gavin Hamilton, 'Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus' (1760-1763)Achilles is the main character of The Illiad, which tells the story of the Trojan War and,

specifically, Achilles' wrath. Achilles and Patroclus are lovers and friends;

angered by Agammemnon, Achilles refuses to fight, but allows Patroclus to wear

his armor and lead the Myrmidons against the Trojans. When Patroclus is killed

by Hector, Achilles is grief-stricken and, enraged, he returns to battle to

destroy the Trojans. The image included here, Gavin Hamilton's Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus (1760-1763), is

housed in National Galleries, Scotland.

Source: Gavin Hamilton, 'Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus' (1760-1763)Achilles is the main character of The Illiad, which tells the story of the Trojan War and,

specifically, Achilles' wrath. Achilles and Patroclus are lovers and friends;

angered by Agammemnon, Achilles refuses to fight, but allows Patroclus to wear

his armor and lead the Myrmidons against the Trojans. When Patroclus is killed

by Hector, Achilles is grief-stricken and, enraged, he returns to battle to

destroy the Trojans. The image included here, Gavin Hamilton's Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus (1760-1763), is

housed in National Galleries, Scotland.

Source: Gavin Hamilton, 'Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus' (1760-1763)Achilles is the main character of The Illiad, which tells the story of the Trojan War and,