"Upon Being Brought from Africa to America"

By

Phillis Wheatley

Transcription, correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Students of Marymount University, James West, Amy Ridderhof

brought The title of one Wheatley's most

(in)famous poems, "On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the

experiences of many Africans who became subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

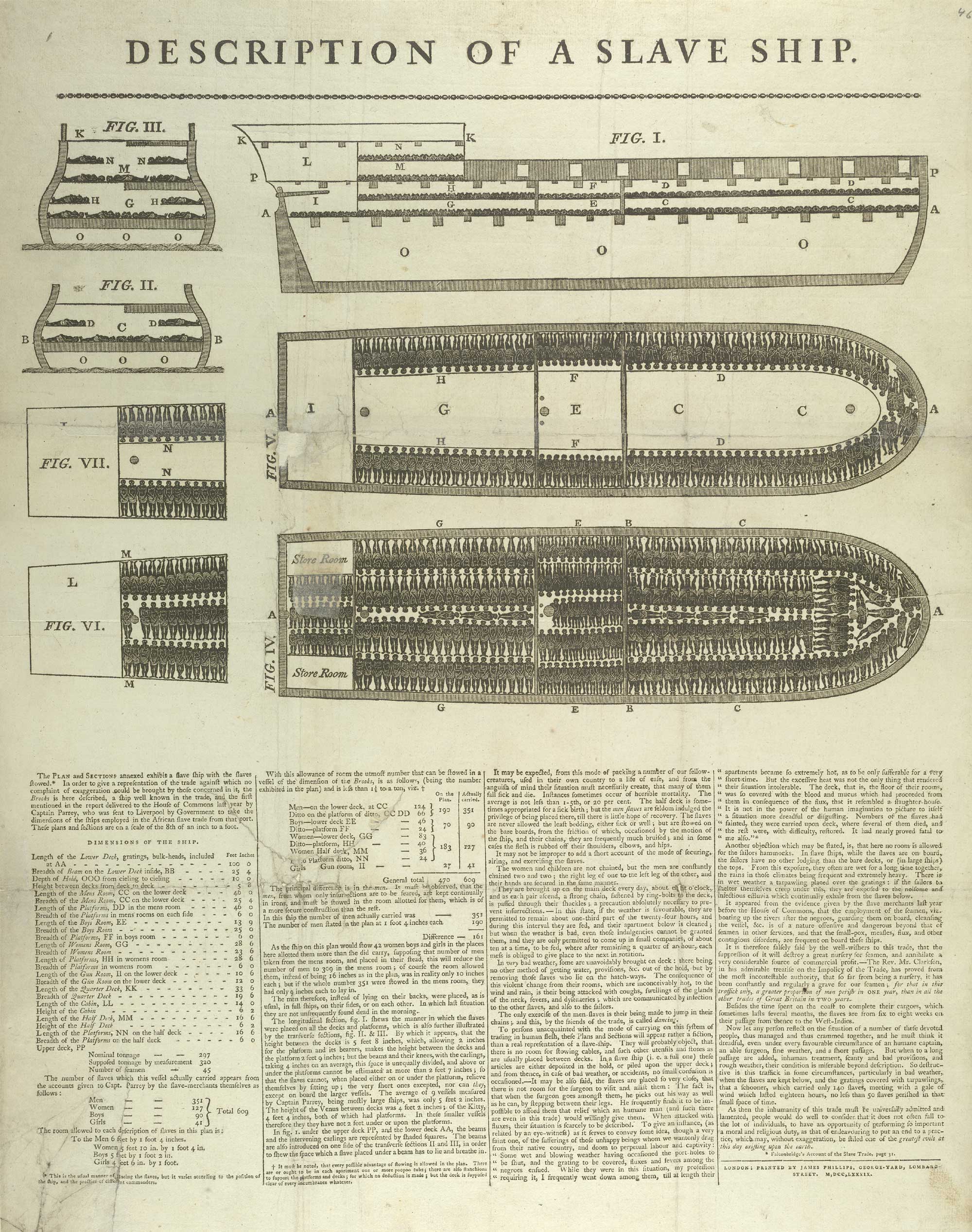

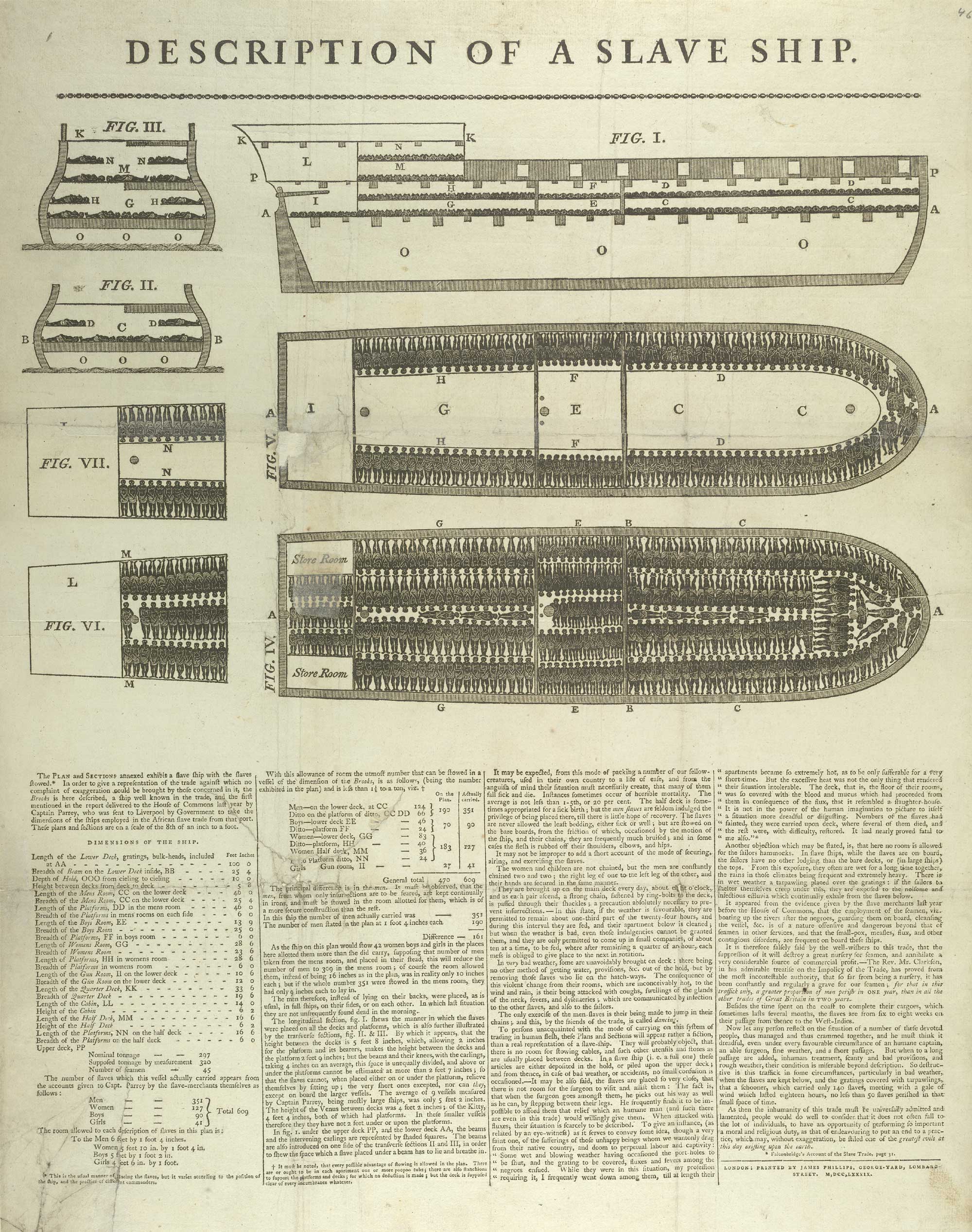

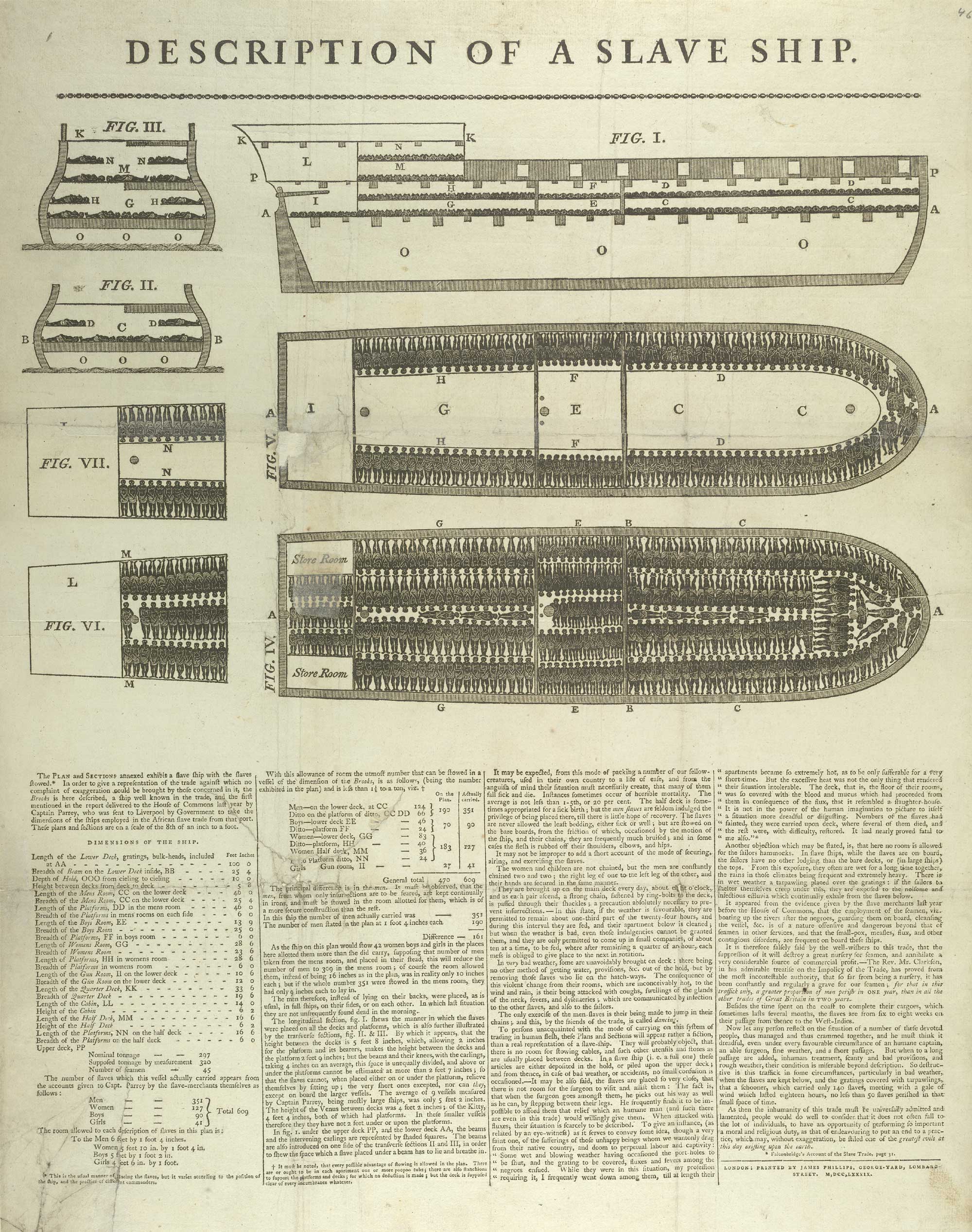

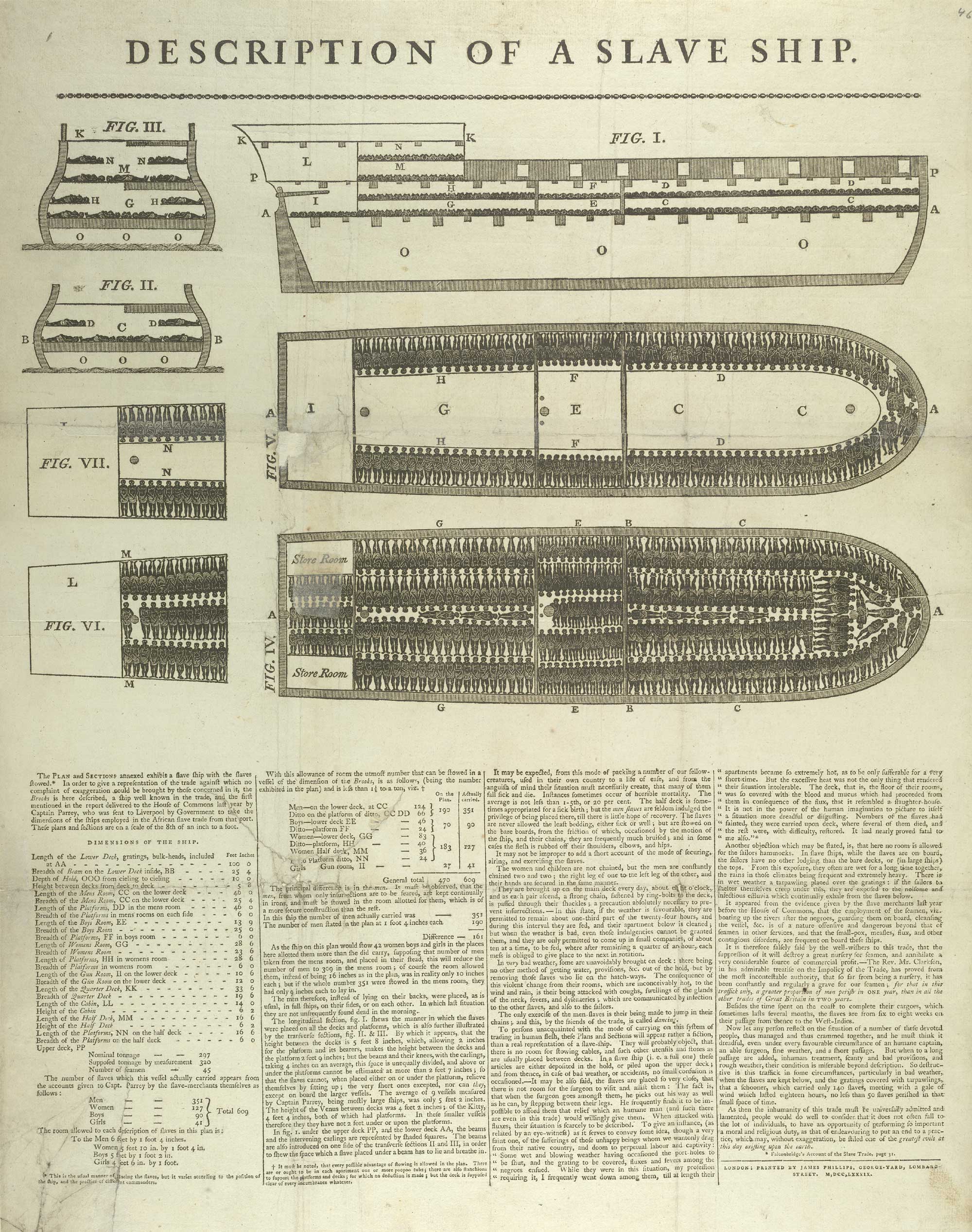

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801). - [JW]someWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

- [TH]CainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)

- [JW]

The title of one Wheatley's most

(in)famous poems, "On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the

experiences of many Africans who became subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801). - [JW]someWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

- [TH]CainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)

- [JW]

The title of one Wheatley's most

(in)famous poems, "On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the

experiences of many Africans who became subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801). - [JW]someWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

- [TH]CainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)

- [JW]

The title of one Wheatley's most

(in)famous poems, "On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the

experiences of many Africans who became subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801). - [JW]someWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

- [TH]CainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)

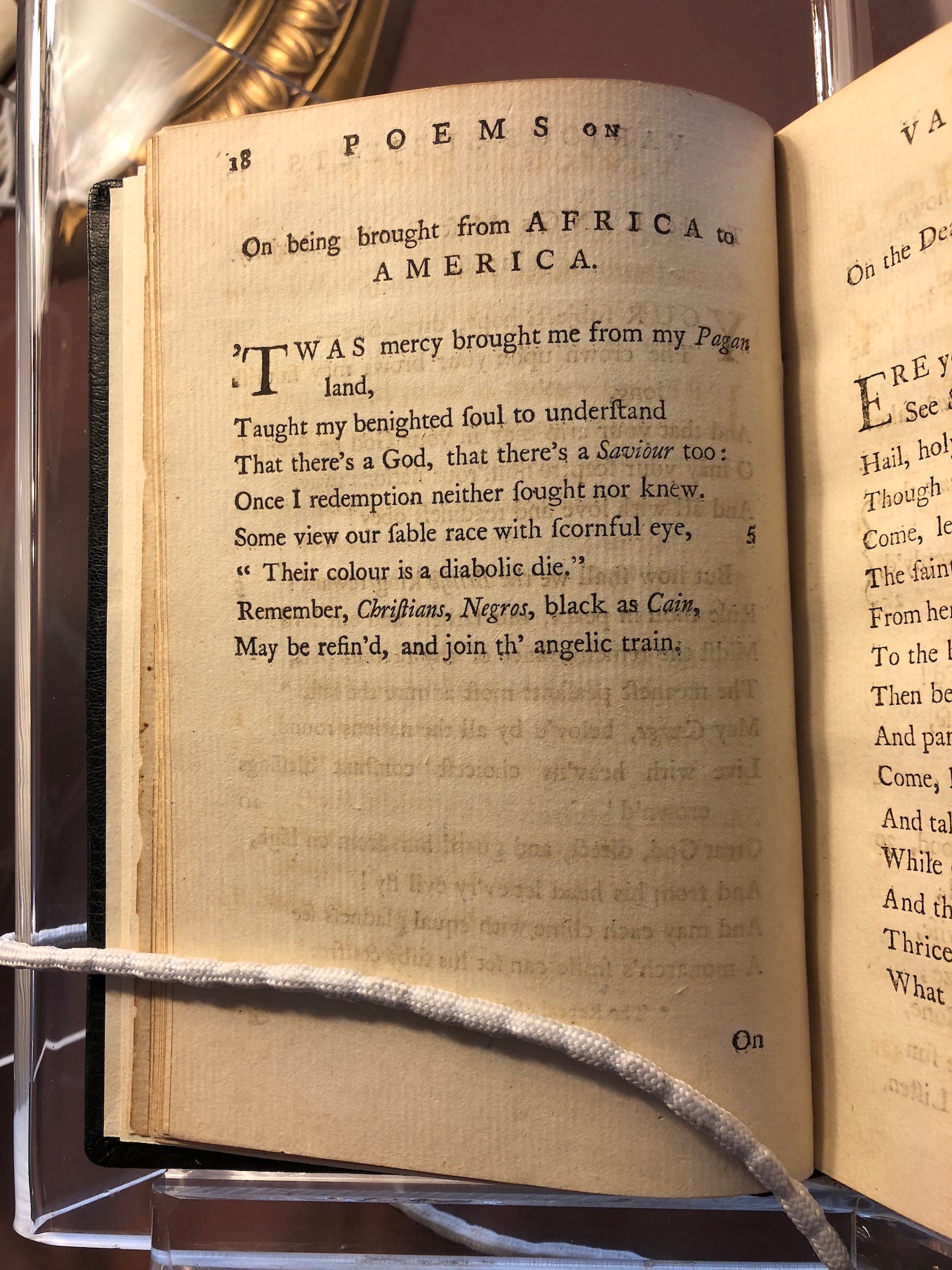

- [JW]18

On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA.broughtbrought The title of one Wheatley's most

(in)famous poems, "On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the

experiences of many Africans who became subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801). - [JW]

1'TWAS mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

2Taught my benighted soul to understand

3That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too:

4Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

5 Some viewsomesomeWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

- [TH] our sable race with scornful eye,

6"Their colour is a diabolic die."

7Remember, Christians, Negros,

black as CainCain,CainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)

- [JW]

8May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train.

The title of one Wheatley's most

(in)famous poems, "On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the

experiences of many Africans who became subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801). - [JW]

1'TWAS mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

2Taught my benighted soul to understand

3That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too:

4Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

5 Some viewsomesomeWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

- [TH] our sable race with scornful eye,

6"Their colour is a diabolic die."

7Remember, Christians, Negros,

black as CainCain,CainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)

- [JW]

8May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train.

The title of one Wheatley's most

(in)famous poems, "On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the

experiences of many Africans who became subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801). - [JW]

1'TWAS mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

2Taught my benighted soul to understand

3That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too:

4Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

5 Some viewsomesomeWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

- [TH] our sable race with scornful eye,

6"Their colour is a diabolic die."

7Remember, Christians, Negros,

black as CainCain,CainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)

- [JW]

8May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train.

The title of one Wheatley's most

(in)famous poems, "On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the

experiences of many Africans who became subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801). - [JW]

1'TWAS mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

2Taught my benighted soul to understand

3That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too:

4Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

5 Some viewsomesomeWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

- [TH] our sable race with scornful eye,

6"Their colour is a diabolic die."

7Remember, Christians, Negros,

black as CainCain,CainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)

- [JW]

8May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train.

Footnotes

_brought The title of one Wheatley's most

(in)famous poems, "On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the

experiences of many Africans who became subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801).

The title of one Wheatley's most

(in)famous poems, "On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the

experiences of many Africans who became subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801).

The title of one Wheatley's most

(in)famous poems, "On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the

experiences of many Africans who became subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801).

The title of one Wheatley's most

(in)famous poems, "On being brought from AFRICA to AMERICA" alludes to the

experiences of many Africans who became subject to the transatlantic slave trade. Wheatley uses biblical references and

direct address to appeal to a Christian audience, while also defending the

ability of her "sable race" to become "refin'd" through Christian theology.

Henry Louis Gates, who in Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self (1989)

situates Wheatley as an important voice in the eighteenth-century debate about

natural human rights, summarizes the "recurrent suggestion that Wheatley has

remained aloof from matters that were in any sense racial, or more correctly,

'positively' racial," as a "misreading" (74-75). Notable for the complexity of

its brief discussion of blackness in the Christian slaveholding American

republic, this poem in particular is frequently criticized for its apparent

rejection of Africa and African-ness. However, Wheatley was working within a

non-free context, and her critique of slavery is mediated by Christianity

acquired as part of her enslavement. For a fuller exploration of Wheatley’s

poem, see Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America,

by William Scheick (especially chapter 4). The image included here,

via the

British Library, shows a diagram of the Brookes' slave ship

(c.1801)._someWheatley's description

of those who "view our sable race with scornful eye" (5) is a clear

rejection of what Lena Hill

describes as "ignorant" interpretations of "visual blackness"

(37-38), as is her attribution of speech in direct discourse:

"'Their color is a diabolic die'" (6). Henry Louis Gates argues that

Wheatley's very presence as an author complicated assumptions of "natural"

inferiority. For more about this topic, see Gates' Figures in

Black and Walt Nott's discussion of Wheatley's public

persona in "From

'Uncultivated Barbarian' to 'Poetical Genius': The Public Presence of

Phillis Wheatley."

_CainThe phrase "black as Cain" is a distortion of the

biblical idea of the mark of Cain (Genesis

4:15) and was used as justification for the enslavement of people

of color. Many scholars point out that this was Wheatley's "most maligned

poem," (Hill

37) which is ultimately about the inclusion of Africans in the

"Christian family" and her critique of "ignorant" interpretations of "visual

blackness" (37-38). For an interesting contemporary read of the mark of Cain

in anti-abolitionist discourse, see Josiah Priest's Slavery as it Relates to the Negro (1843), where he

rejects the possibility that dark-skinned peoples could be related to Adam

by blood (134-136). For a larger reading of Wheatley's use of blackness and

the role of blackness in the early American imagination, see Lena Hill's

chapter "Witnessing Moral Authority in Pre-Abolition Literature," from Visualizing

Blackness and the Creation of the African American Literary

Tradition (2014)