The Castle of Otranto

By

Horace Walpole

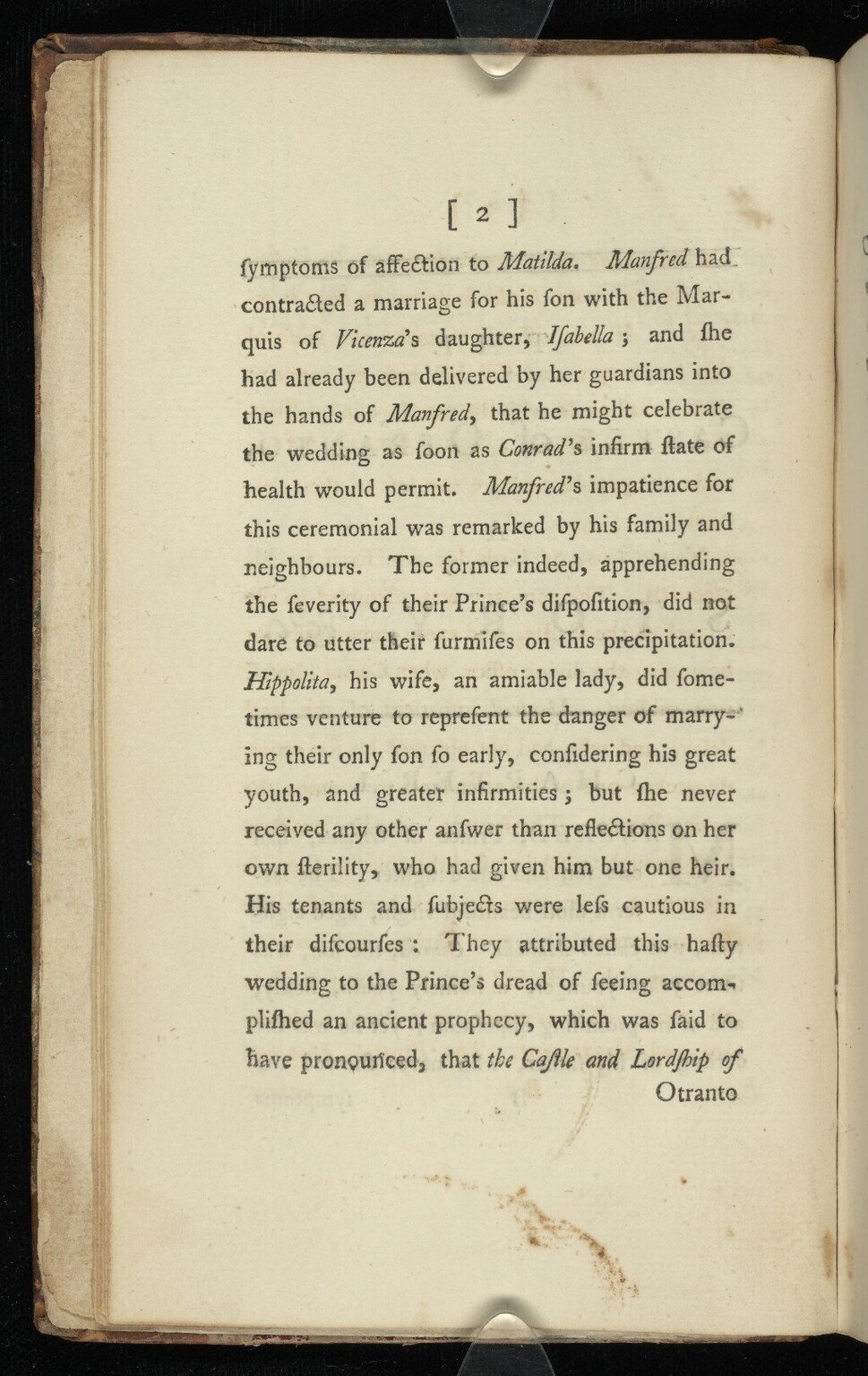

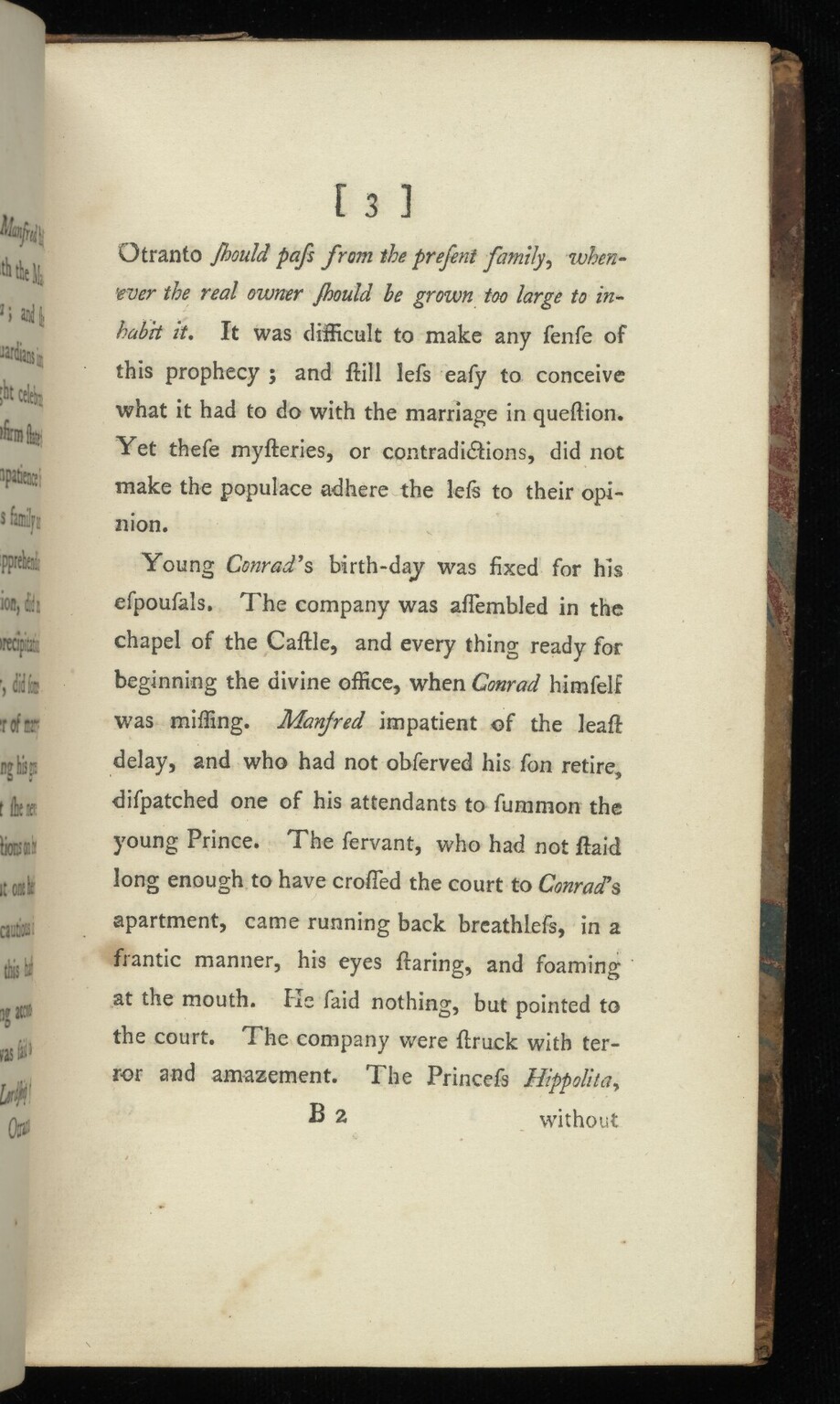

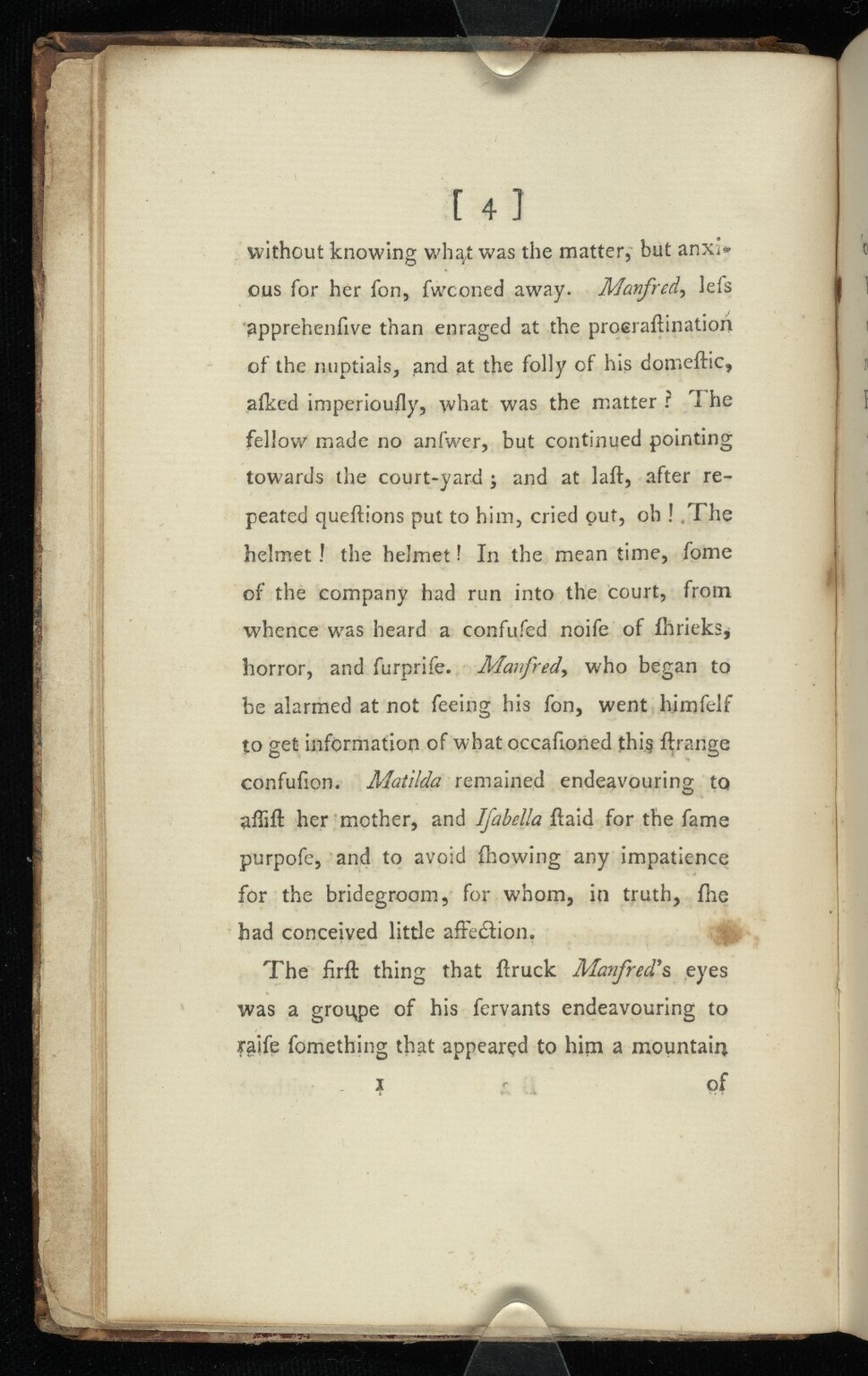

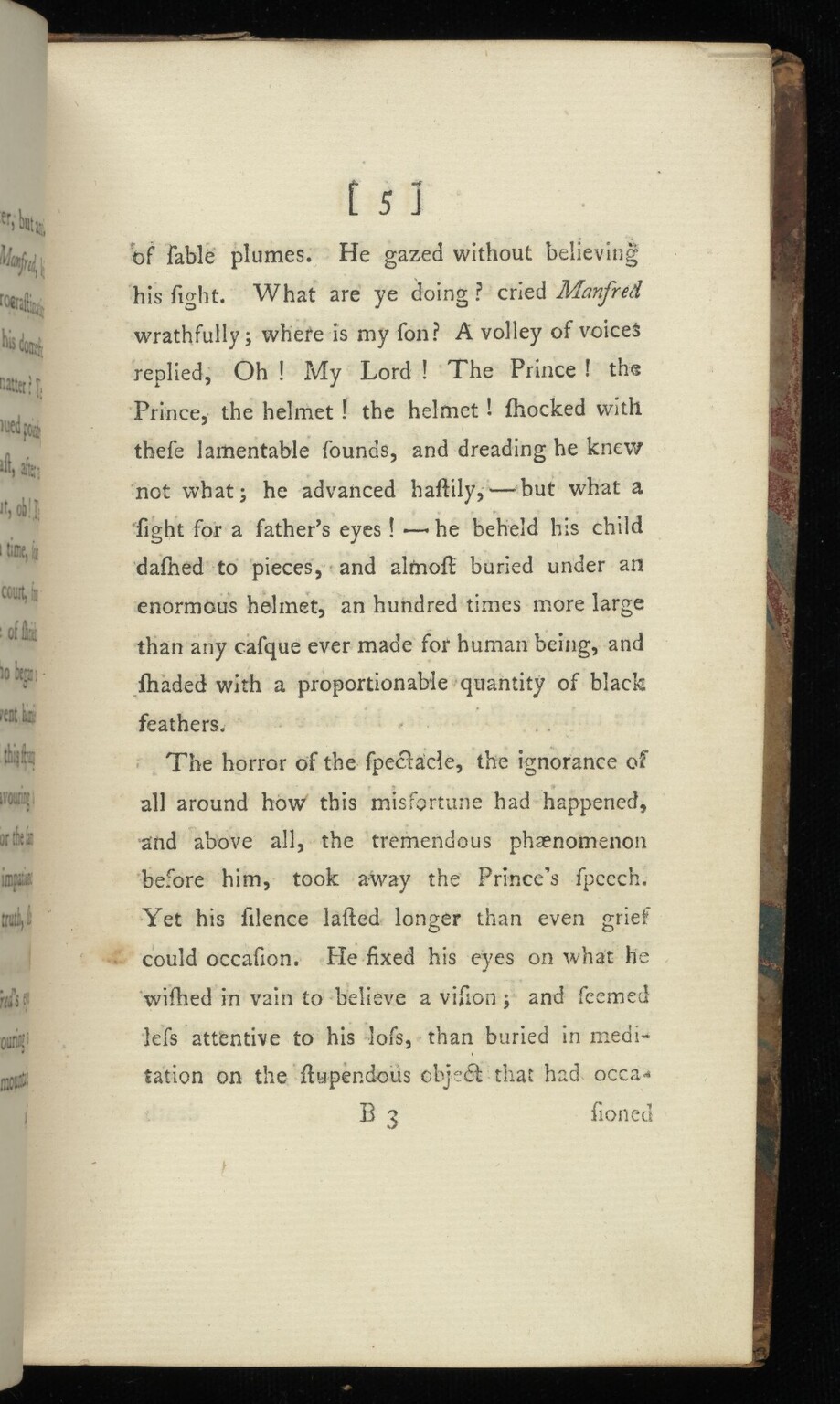

Correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Students and Staff of Marymount University

CastleThe Castle of Otranto is often referred to as the first Gothic novel. Which is fair enough, so far as it goes; Horace Walpole’s novel did establish many key features of the Gothic genre, which has been popular with readers ever since The Castle of Otranto was first published on Christmas Eve, 1764. Like the Gothic novels, plays, stories, and films that followed it, The Castle of Otranto teases us by suggesting that the rules of the everyday world do not always apply, that sometimes only a supernatural explanation can account for everything that we see. That idea—which goes against the grain of the assumption that the modern novel is all about realism—runs through books like Anne Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight series and thousands more works of fiction, be they written as stories or novels, or filmed for cinema or television.

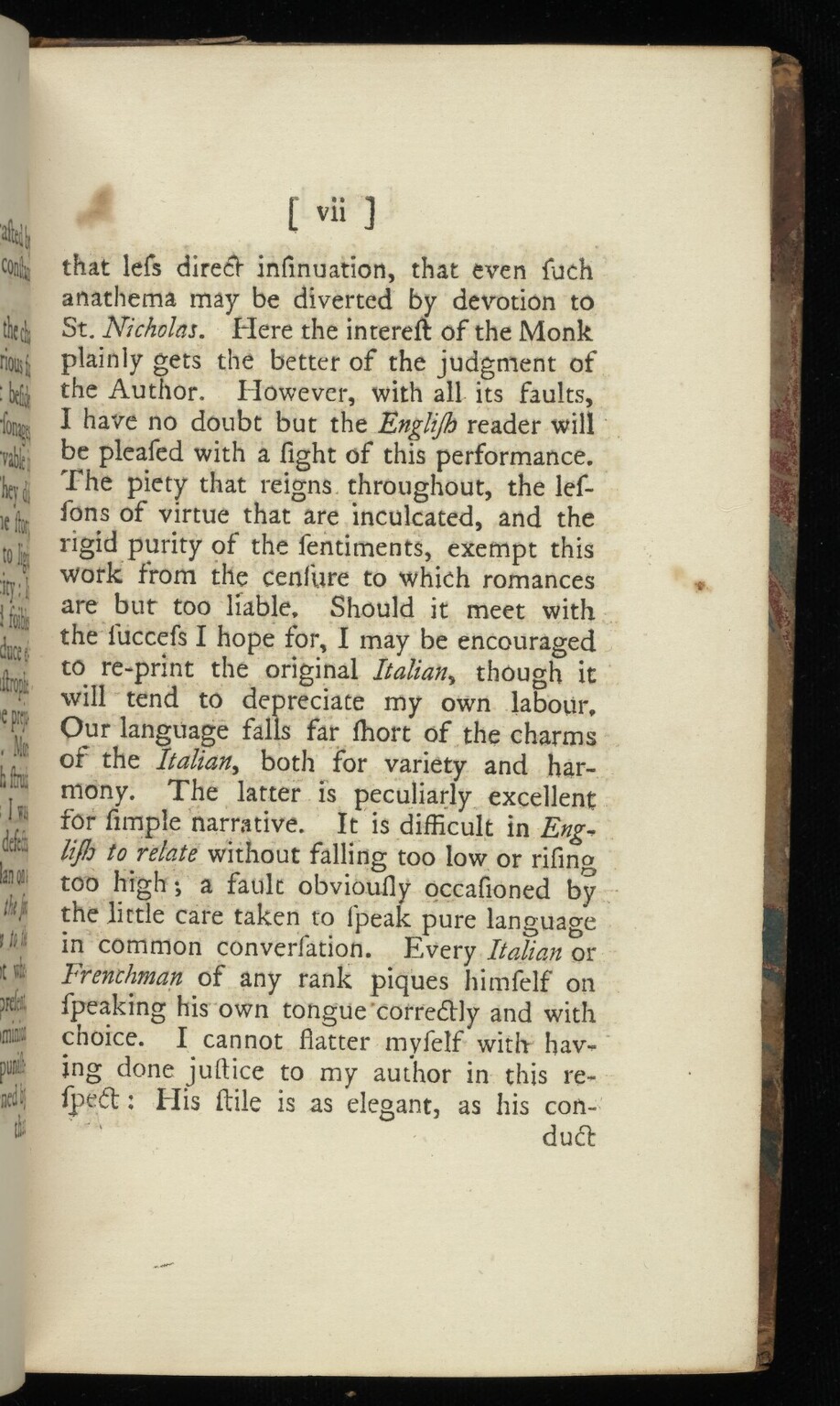

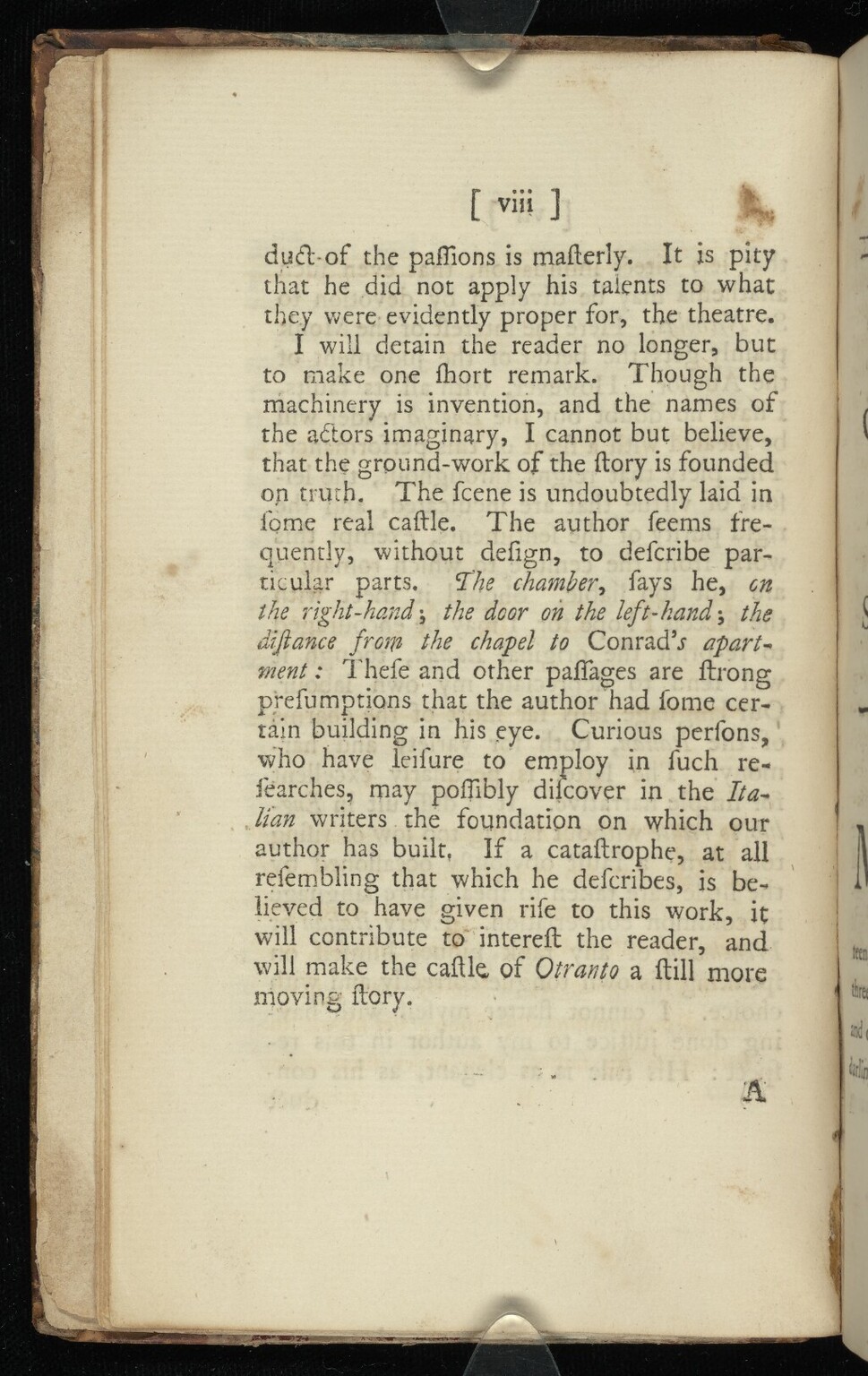

But of course Horace Walpole did not know that all of these works would follow from The Castle of Otranto; he was not setting out to found what would become the first fully-fledged sub-genre of the English novel. What did he think he was doing? One thing he was surely trying to do was to perpetrate a good hoax. When it was first published in 1764, The Castle of Otranto claimed to be a translation of an Italian manuscript from 1529 that was telling a story originally written hundreds of years before that. Walpole’s original preface, written in the voice of the imaginary “William Marshall,” the putative translator, claims that a sixteenth-century Italian printing of the book was found in a library in Naples, but that the story must have been in manuscript centuries earlier. That is an utter fabrication. But it was a good one; some of the book’s first readers seem to have bought the ruse at first (the reviewer for the Monthly Review complained at having been duped when Walpole’s second preface, published in 1765, revealed his authorship and the fact that the book was a contemporary work of fiction.) Eighteenth-century readers often loved how the anonymity of print enabled hoaxes, and The Castle of Otranto joins works like Gulliver’s Travels in exploiting the general desire that all readers have to believe that something quite fantastic is in fact true.

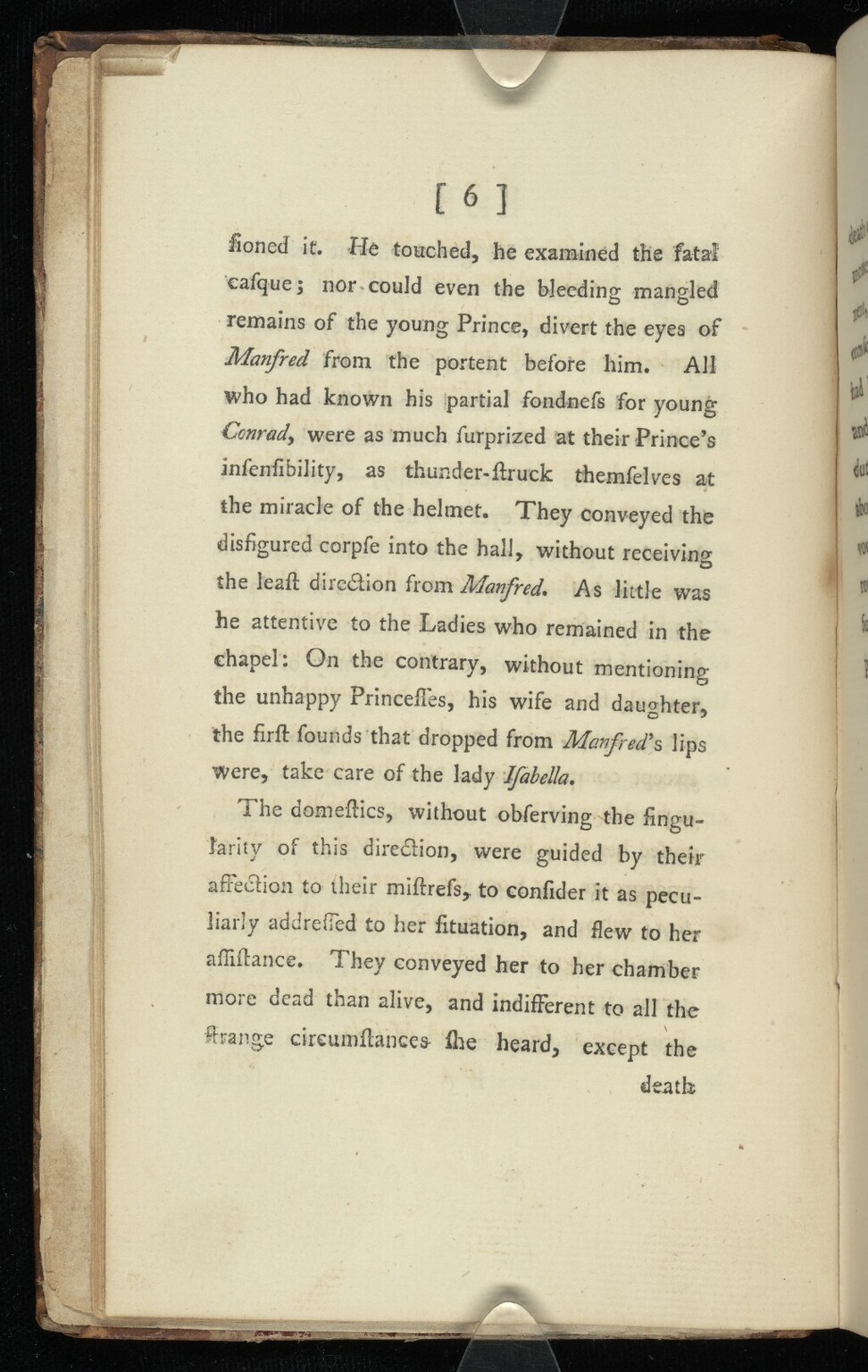

The two prefaces—the first, fake one by “Marshall” and the second one in the voice of the author himself—offer important clues to what Walpole thought were The Castle of Otranto’s main innovations. Walpole wanted to combine some of the thrill of older "romances" with some of the historical specificity of modern fiction. And, most of all, he wanted to entertain his readers. The success of the book--which has never been out of print--and the medium it created--testify to Walpole's success. - [JOB]casquea helmet

[titlepage]

THE

CASTLE of OTRANTO,

A

STORY.

CastleCastleThe Castle of Otranto is often referred to as the first Gothic novel. Which is fair enough, so far as it goes; Horace Walpole’s novel did establish many key features of the Gothic genre, which has been popular with readers ever since The Castle of Otranto was first published on Christmas Eve, 1764. Like the Gothic novels, plays, stories, and films that followed it, The Castle of Otranto teases us by suggesting that the rules of the everyday world do not always apply, that sometimes only a supernatural explanation can account for everything that we see. That idea—which goes against the grain of the assumption that the modern novel is all about realism—runs through books like Anne Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight series and thousands more works of fiction, be they written as stories or novels, or filmed for cinema or television. But of course Horace Walpole did not know that all of these works would follow from The Castle of Otranto; he was not setting out to found what would become the first fully-fledged sub-genre of the English novel. What did he think he was doing? One thing he was surely trying to do was to perpetrate a good hoax. When it was first published in 1764, The Castle of Otranto claimed to be a translation of an Italian manuscript from 1529 that was telling a story originally written hundreds of years before that. Walpole’s original preface, written in the voice of the imaginary “William Marshall,” the putative translator, claims that a sixteenth-century Italian printing of the book was found in a library in Naples, but that the story must have been in manuscript centuries earlier. That is an utter fabrication. But it was a good one; some of the book’s first readers seem to have bought the ruse at first (the reviewer for the Monthly Review complained at having been duped when Walpole’s second preface, published in 1765, revealed his authorship and the fact that the book was a contemporary work of fiction.) Eighteenth-century readers often loved how the anonymity of print enabled hoaxes, and The Castle of Otranto joins works like Gulliver’s Travels in exploiting the general desire that all readers have to believe that something quite fantastic is in fact true. The two prefaces—the first, fake one by “Marshall” and the second one in the voice of the author himself—offer important clues to what Walpole thought were The Castle of Otranto’s main innovations. Walpole wanted to combine some of the thrill of older "romances" with some of the historical specificity of modern fiction. And, most of all, he wanted to entertain his readers. The success of the book--which has never been out of print--and the medium it created--testify to Walpole's success. - [JOB]

Translated by

WILLIAM MARSHAL, Gent.

From the Original ITALIAN of

ONUPHRIO MURALTO,

CANON of the Church of St. NICHOLAS

at OTRANTO.

LONDON:

Printed for THO. LOWNDS in Fleet-Street.

MDCCLXV.

CASTLE of OTRANTO,

A

STORY.

CastleCastleThe Castle of Otranto is often referred to as the first Gothic novel. Which is fair enough, so far as it goes; Horace Walpole’s novel did establish many key features of the Gothic genre, which has been popular with readers ever since The Castle of Otranto was first published on Christmas Eve, 1764. Like the Gothic novels, plays, stories, and films that followed it, The Castle of Otranto teases us by suggesting that the rules of the everyday world do not always apply, that sometimes only a supernatural explanation can account for everything that we see. That idea—which goes against the grain of the assumption that the modern novel is all about realism—runs through books like Anne Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight series and thousands more works of fiction, be they written as stories or novels, or filmed for cinema or television. But of course Horace Walpole did not know that all of these works would follow from The Castle of Otranto; he was not setting out to found what would become the first fully-fledged sub-genre of the English novel. What did he think he was doing? One thing he was surely trying to do was to perpetrate a good hoax. When it was first published in 1764, The Castle of Otranto claimed to be a translation of an Italian manuscript from 1529 that was telling a story originally written hundreds of years before that. Walpole’s original preface, written in the voice of the imaginary “William Marshall,” the putative translator, claims that a sixteenth-century Italian printing of the book was found in a library in Naples, but that the story must have been in manuscript centuries earlier. That is an utter fabrication. But it was a good one; some of the book’s first readers seem to have bought the ruse at first (the reviewer for the Monthly Review complained at having been duped when Walpole’s second preface, published in 1765, revealed his authorship and the fact that the book was a contemporary work of fiction.) Eighteenth-century readers often loved how the anonymity of print enabled hoaxes, and The Castle of Otranto joins works like Gulliver’s Travels in exploiting the general desire that all readers have to believe that something quite fantastic is in fact true. The two prefaces—the first, fake one by “Marshall” and the second one in the voice of the author himself—offer important clues to what Walpole thought were The Castle of Otranto’s main innovations. Walpole wanted to combine some of the thrill of older "romances" with some of the historical specificity of modern fiction. And, most of all, he wanted to entertain his readers. The success of the book--which has never been out of print--and the medium it created--testify to Walpole's success. - [JOB]

Translated by

WILLIAM MARSHAL, Gent.

From the Original ITALIAN of

ONUPHRIO MURALTO,

CANON of the Church of St. NICHOLAS

at OTRANTO.

LONDON:

Printed for THO. LOWNDS in Fleet-Street.

MDCCLXV.

![Page [titlepage]](https://anthologyassetsdev.lib.virginia.edu/walpole-castle/pageImages/TP.jpg)

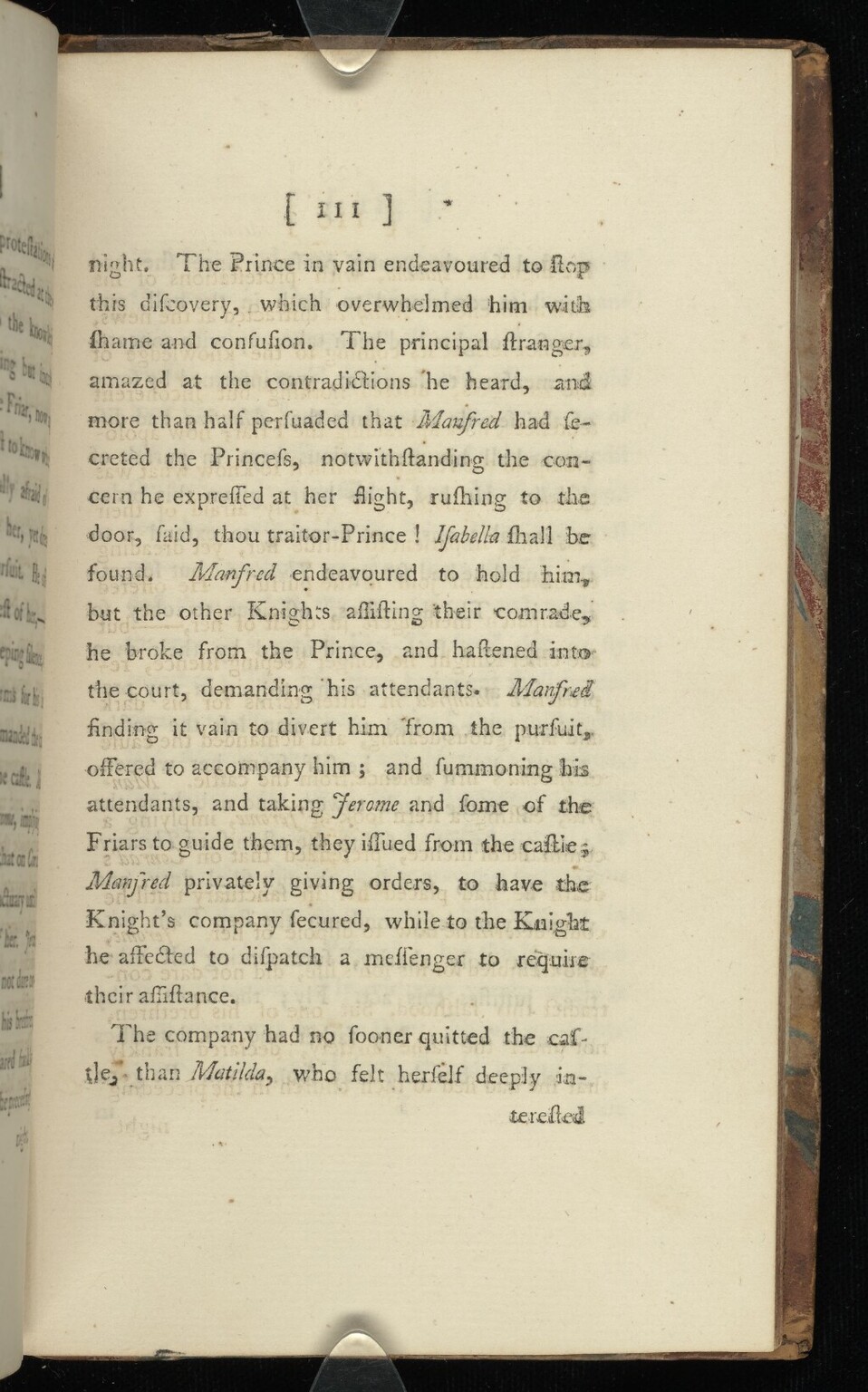

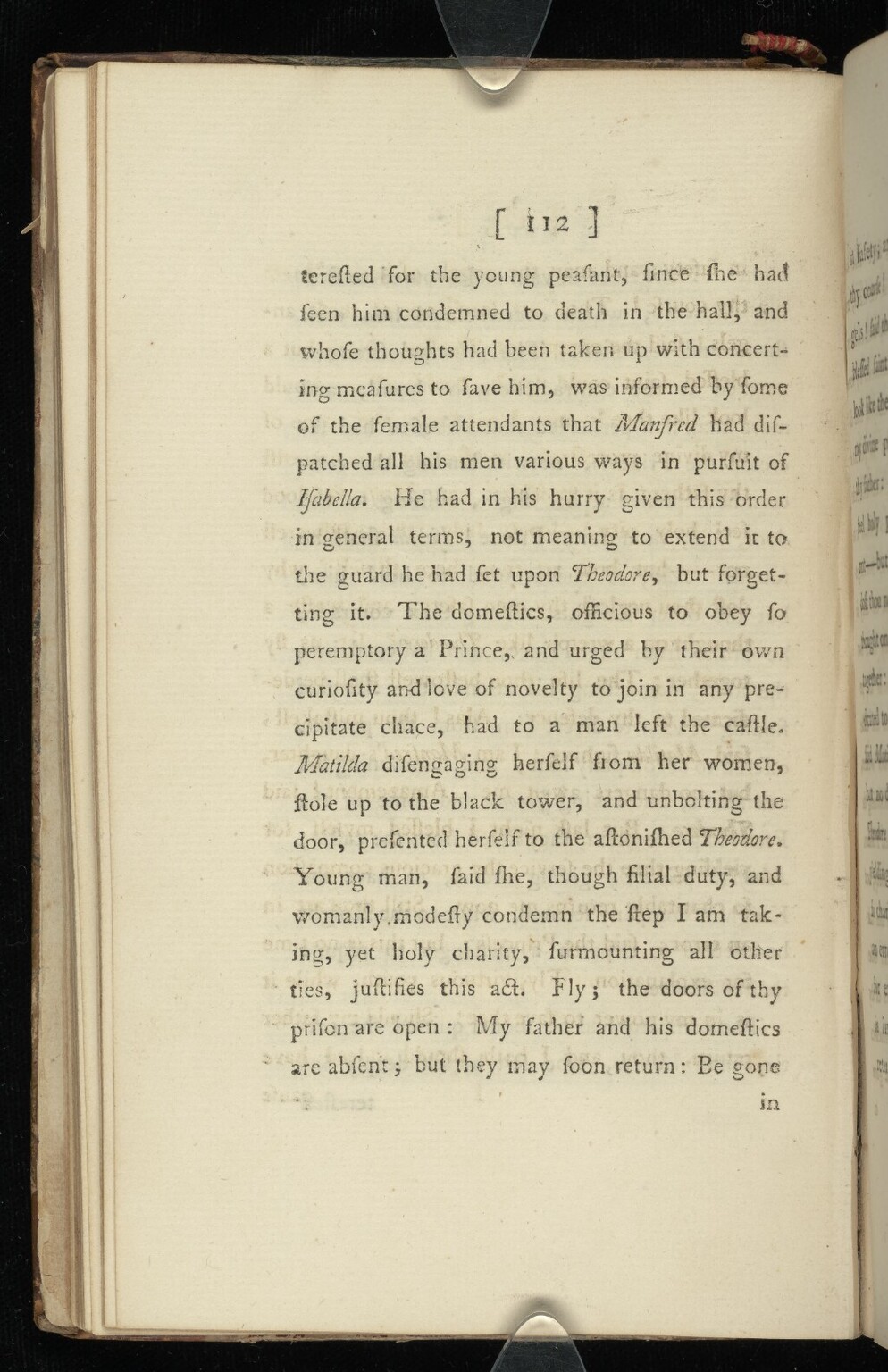

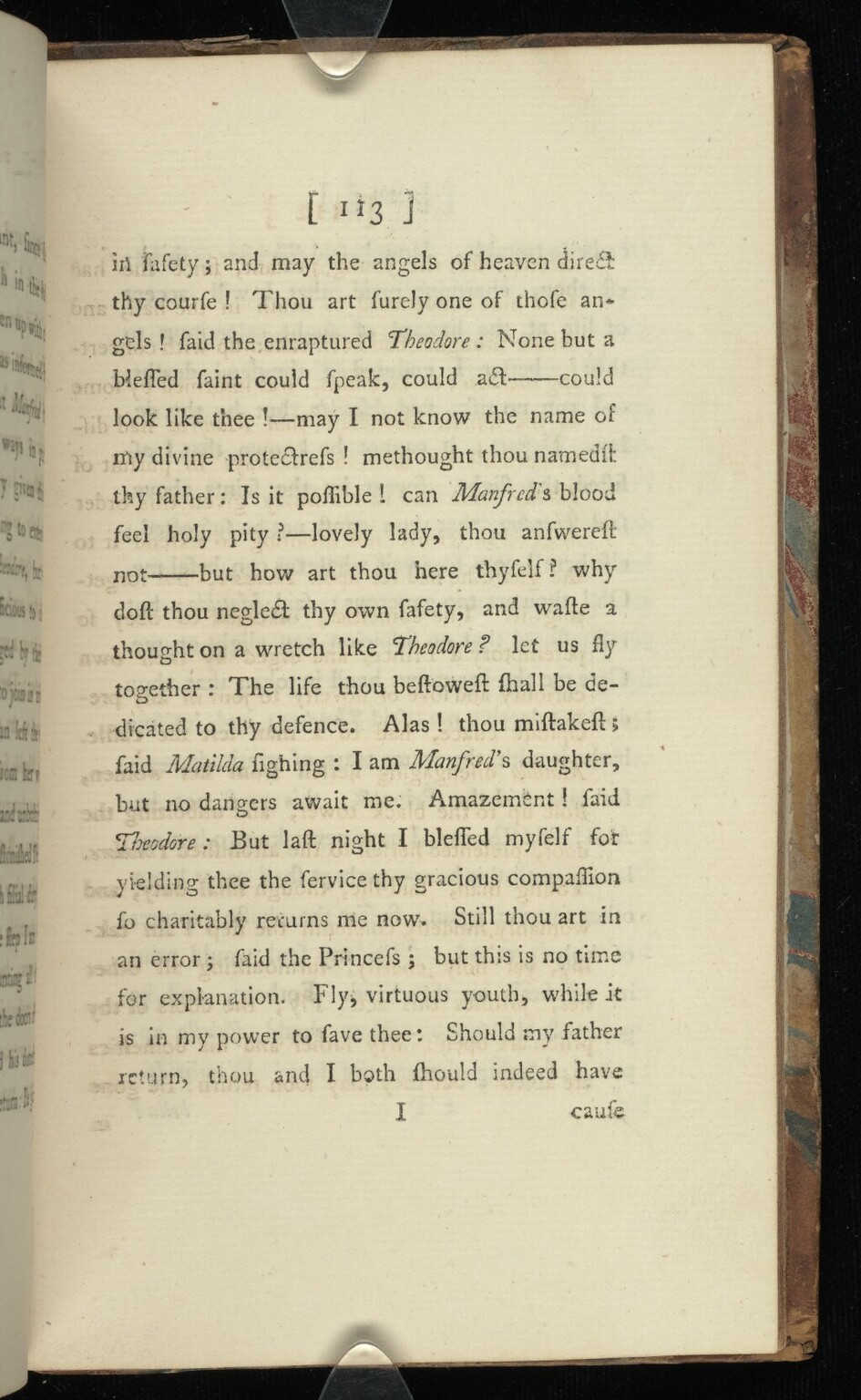

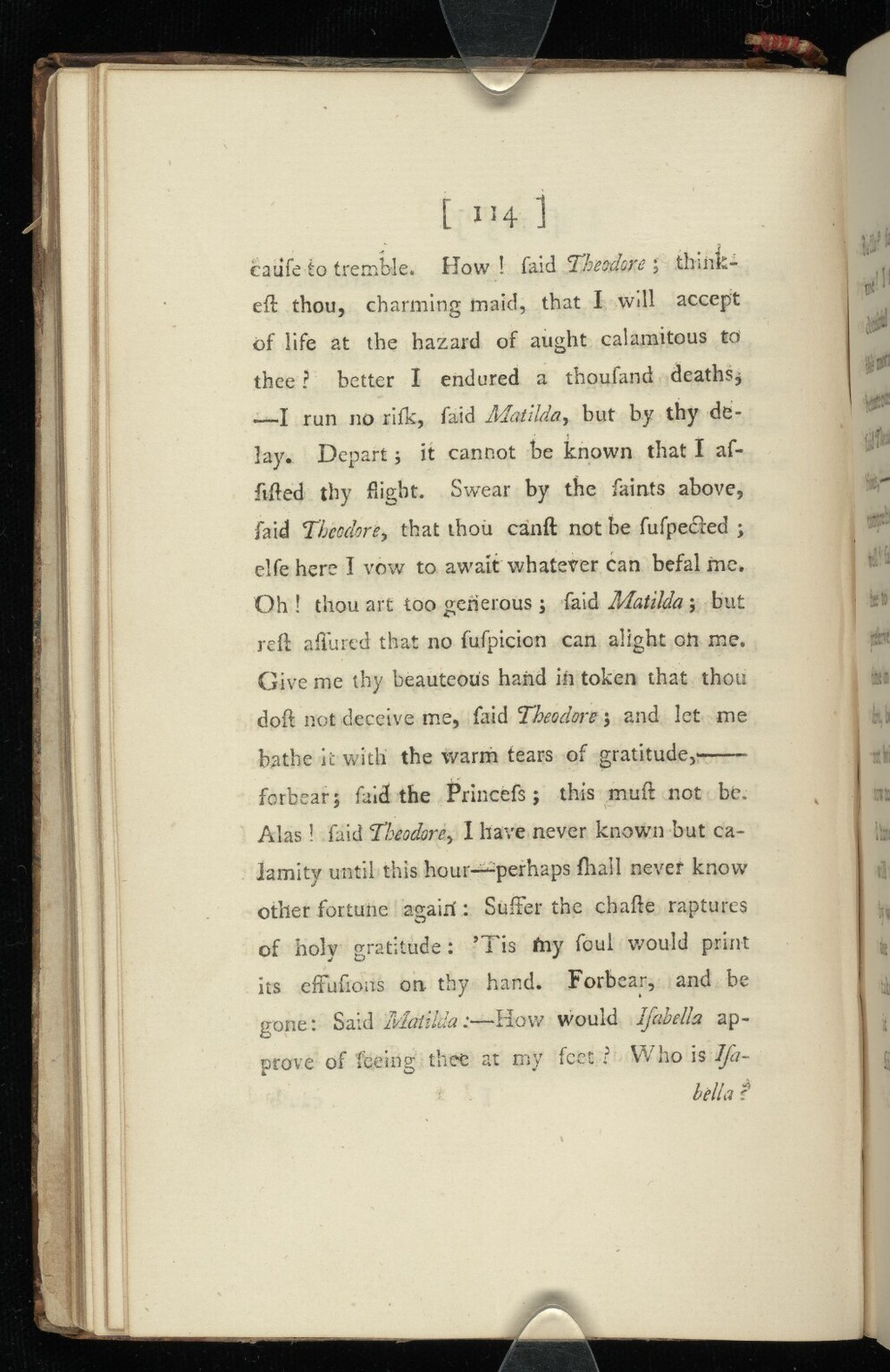

![Page [iii]](https://anthologyassetsdev.lib.virginia.edu/walpole-castle/pageImages/iii.jpg)

![Page [1]](https://anthologyassetsdev.lib.virginia.edu/walpole-castle/pageImages/001.jpg)