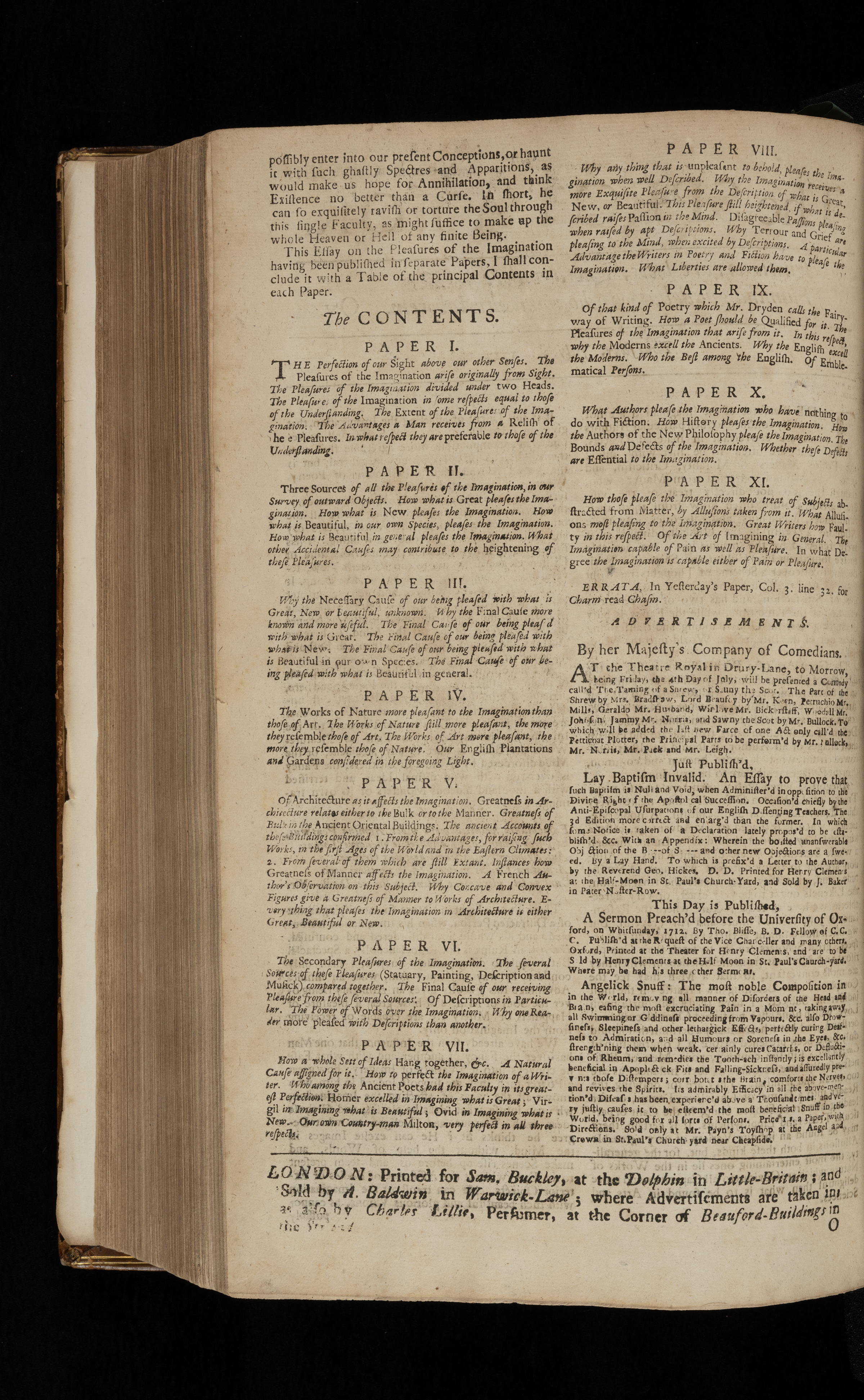

The Spectator, Issue 421, Thursday, July 3, 1712

By

Joseph Addison

Ignotis errare locis, ignota videreIgnotisIgnotis"Delighting to wander in unknown lands and to see strange rivers, his eagerness making light of toil." from the Metamorphoses of the Roman poet Ovid. Loeb Classical Library translation. Flumina gaudebat; studio minuente laborem. Ovid. Thursday, July 3, 1712.

The Pleasures of the Imagination are not wholly confined to such particular Authors as are conversant in material Objects, but are often to be met with among the Polite Masters of Morality, Criticism, and other Speculations abstracted from Matter, who, tho' they do not directly treat of the visible Parts of Nature, often draw from them their Similitudes, Metaphors, and Allegories. By these Allusions a Truth in the Understanding is as it were reflected by the Imagination; we are able to see something like Colour and Shape in a Notion, and to discover a Scheme of Thoughts traced out upon Matter. And here the Mind receives a great deal of Satisfaction, and has two of its Faculties gratified at the same time, while the Fancy is busie in copying after the Understanding, and transcribing Ideas out of the Intellectual World into the Material.

The Great Art of a Writer shews it self in the Choice of pleasing Allusions, which are generally to be taken from the great or beautiful Works of Art or Nature; for though whatever is New or Uncommon is apt to delight the Imagination, the chief Design of an Allusion being to illustrate and explain the Passages of an Author, it should be always borrowed from what is more known and common, than the Passages which are to be explained.

Allegories, when well chosen, are like so many Tracks of Light in a Discourse, that make every thing about them clear and beautiful. A noble Metaphor, when it is placed to an Advantage, casts a kind of Glory round it, and darts a Lustre through a whole Sentence: These different Kinds of Allusion are but so many different Manners of Similitude, and, that they may please the Imagination, the Likeness ought to be very exact, or very agreeable, as we love to see a Picture where the Resemblance is just, or the Posture and Air graceful. But we often find eminent Writers very faulty in this respect; great Scholars are apt to fetch their Comparisons and Allusions from the Sciences in which they are most conversant, so that a Man may see the Compass of their Learning in a Treatise on the most indifferent Subject. I have read a Discourse upon Love, which none but a profound Chymist could understand, and have heard many a Sermon that should only have been preached before a Congregation of Cartesians. On the contrary, your Men of Business usually have recourse to such Instances as are too mean and familiar. They are for drawing the Reader into a Game of Chess or Tennis, or for leading him from Shop to Shop, in the Cant of particular Trades and Employments. It is certain, there may be found an infinite Variety of very agreeable Allusions in both these kinds, but for the generality, the most entertaining ones lie in the Works of Nature, which are obvious to all Capacities, and more delightful than what is to be found in Arts and Sciences.

It is this Talent of affecting the Imagination, that gives an Embellishment to good Sense, and makes one Man's Compositions more agreeable than another's. It sets off all Writings in general, but is the very Life and highest Perfection of Poetry: Where it shines in an Eminent Degree, it has preserved several Poems for many Ages, that have nothing else to recommend them; and where all the other Beauties are present, the Work appears dry and insipid, if this single one be wanting. It has something in it like Creation; It bestows a kind of Existence, and draws up to the Reader's View several Objects which are not to be found in Being. It makes Additions to Nature, and gives a greater Variety to God's Works. In a Word, it is able to beautifie and adorn the most illustrious Scenes in the Universe, or to fill the Mind with more glorious Shows and Apparitions, than can be found in any Part of it.

We have now discovered the several Originals of those Pleasures that gratify the Fancy; and here, perhaps, it would not be very difficult to cast under their proper Heads those contrary Objects, which are apt to fill it with Distaste and Terrour; for the Imagination is as liable to Pain as Pleasure. When the Brain is hurt by any Accident, or the Mind disordered by Dreams or Sickness, the Fancy is over-run with wild dismal Ideas, and terrified with a thousand hideous Monsters of its own framing.

Eumenidum veluti demens videt Agmina Pentheus,EumenidumEumenidum"Thus frantic Penthus flees the stern array of the Eumenides, and thinks to see two noonday lights blaze on his doubled Thebes; or murdered Agamemnon's haunted son, Orestes, flees his mother's phantom scourge of flames and serpents foul, while at his door avenging horrors wait." from book IV of Virgil's Aeneid. Perseus Classical Library translation. Et solem geminum, et duplices se ostendere Thebas. Aut Agamemnonius scenis agitatus Orestes, Armatam facibus matrem et serpentibus atris Cum videt, ultricesque sedent in limine Diræ. Vir.There is not a Sight in Nature so mortifying as that of a Distracted Person, when his Imagination is troubled, and his whole Soul disordered and confused. Babylon in Ruins is not so melancholy a Spectacle. But to quit so disagreeable a Subject, I shall only consider, by way of Conclusion, what an infinite Advantage this Faculty gives an Almighty Being over the Soul of Man, and how great a measure of Happiness or Misery we are capable of receiving from the Imagination only.

We have already seen the Influence that one Man has over the Fancy of another, and with what Ease he conveys into it a Variety of Imagery; how great a Power then may we suppose lodged in him, who knows all the ways of affecting the Imagination, who can infuse what Ideas he pleases, and fill those Ideas with Terrour and Delight to what Degree he thinks fit? He can excite Images in the Mind, without the help of Words, and make Scenes rise up before us and seem present to the Eye without the Assistance of Bodies or Exterior Objects. He can transport the Imagination with such beautiful and glorious Visions, as cannot