The Spectator, Issue 412, Monday, June 12, 1712

By

Joseph Addison

Divisum sic breve fiet Opus.-----------Mart.MartMart"The task, broken up, becomes shorter." from the Epigrams of the Roman poet Martial.

Monday, June 23. 1712

I shall first consider those Pleasures of the Imagination, which arise from the actual View and Survey of outward Objects: And these, I think, all proceed from the Sight of what is Great, Uncommon, or Beautiful. There may, indeed, be something so terrible or offensive, that the Horror or Loathsomeness of an Object may over-bear the Pleasure which results from its Greatness, Novelty, or Beauty; but still there will be such a Mixture of Delight in the very Disgust it gives us, as any of these three Qualifications are most conspicuous and prevailing.

By Greatness, I do not only mean the Bulk of any single Object, but the Largeness of a whole View, considered as one entire Piece. Such are the Prospects of an open Champain Country, a vast uncultivated Desart, of huge Heaps of Mountains, high Rocks and Precipices, or a wide Expanse of Waters, where we are not struck with the Novelty or Beauty of the Sight, but with that rude kind of Magnificence which appears in many of these stupendous Works of Nature. Our Imagination loves to be filled with an Object, or to grasp at any thing that is too big for its Capacity. We are flung into a pleasing Astonishment at such unbounded Views, and feel a delightful Stillness and Amazement in the Soul at the Apprehension of them. The Mind of Man naturally hates every thing that looks like a Restraint upon it, and is apt to fancy it self under a sort of Confinement, when the Sight is pent up in a narrow Compass, and shortned on every side by the Neighbourhood of Walls or Mountains. On the contrary, a spacious Horizon is an Image of Liberty, where the Eye has Room to range abroad, to expatiate at large on the Immensity of its Views, and to lose it self amidst the Variety of Objects that offer themselves to its Observation. Such wide and undetermined Prospects are as pleasing to the Fancy, as the Speculations of Eternity or Infinitude are to the Understanding. But if there be a Beauty or Uncommonness joined with this Grandeur, as in a troubled Ocean, a Heaven adorned with Stars and Meteors, or a spacious LandskipLandskipLandskipLandscape cut out into Rivers, Woods, Rocks, and Meadows, the Pleasure still grows upon us, as it rises from more than a single Principle.

Every thing that is new or uncommon raises a Pleasure in the Imagination, because it fills the Soul with an agreeable Surprize, gratifies its Curiosity, and gives it an Idea of which it was not before possest. We are indeed so often conversant with one Set of Objects, and tired out with so many repeated Shows of the same Things, that whatever is new or uncommon contributes a little to vary human Life, and to divert our Minds, for a while, with the Strangeness of its Appearance: It serves us for a kind of Refreshment, and takes off from that Satiety we are apt to complain of in our usual and ordinary Entertainments. It is this that bestows Charms on a Monster, and makes even the Imperfections of Nature please us. It is this that recommends Variety, where the Mind is every Instant called off to something new, and the Attention not suffered to dwell too long, and waste it self on any particular Object. It is this, likewise, that improves what is great or beautiful, and make it afford the Mind a double Entertainment. Groves, Fields, and Meadows, are at any Season of the Year pleasant to look upon, but never so much as in the Opening of the Spring, when they are all new and fresh, with their first Gloss upon them, and not yet too much accustomed and familiar to the Eye. For this Reason there is nothing that more enlivens a Prospect than Rivers, Jetteaus, or Falls of Water, where the Scene is perpetually shifting, and entertaining the Sight every Moment with something that is new. We are quickly tired with looking upon Hills and Vallies, where every thing continues fixed and settled in the same Place and Posture, but find our Thoughts a little agitated and relieved at the Sight of such Objects as are ever in Motion, and sliding away from beneath the Eye of the Beholder.

But there is nothing that makes its Way more directly to the Soul than Beauty, which immediately diffuses a secret Satisfaction and Complacency through the Imagination, and gives a Finishing to any thing that is Great or Uncommon. The very first Discovery of it strikes the Mind with an inward Joy, and spreads a Chearfulness and Delight through all its Faculties. There is not perhaps any real Beauty or Deformity more in one Piece of Matter than another, because we might have been so made, that whatsoever now appears loathsome to us, might have shewn it self agreeable; but we find by Experience, that there are several Modifications of Matter which the Mind, without any previous Consideration, pronounces at first sight Beautiful or Deformed. Thus we see that every different Species of sensible Creatures has its different Notions of Beauty, and that each of them is most affected with the Beauties of its own Kind. This is no where more remarkable than in Birds of the same Shape and Proportion, where we often see the Male determined in his Courtship by the single Grain or Tincture of a Fea- Versother, and never discovering any Charms but in the Colour of its Species.

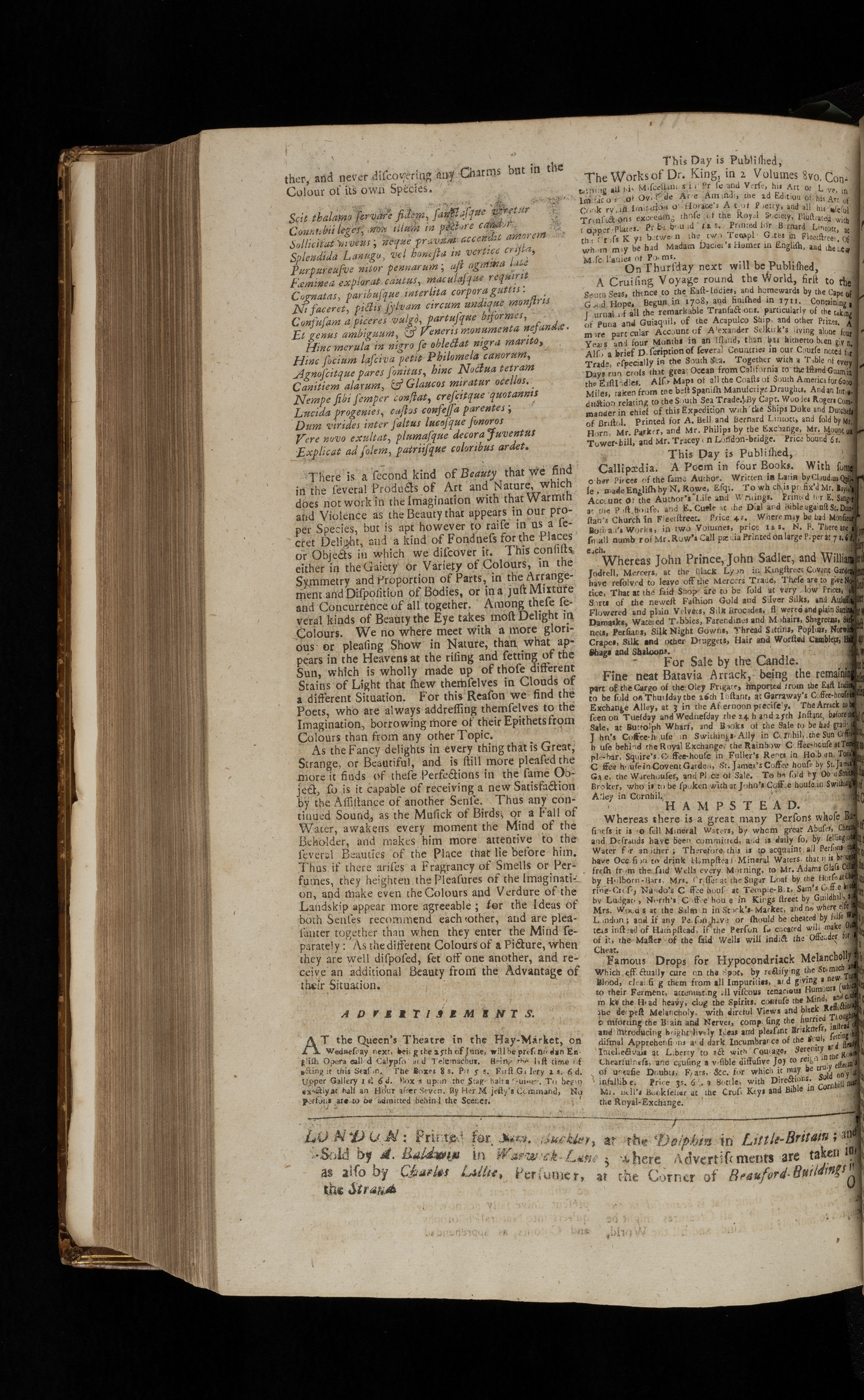

Scit thalamo servare fidem, sanctasque vereturScit Connubii leges, non illum in pectore candor Sollicitat niveus; neque pravum accendit amorem Splendida Lanugo, vel honesta in vertice crista, Purpureusve nitor pennarum; ast agmina latè Fœminea explorat cautus, maculasque requirit Cognatas, paribusque interlita corpora guttis: Ni faceret, pictis sylvam circum undique monstris Confusam aspiceres vulgò, partusque biformes, Et genus ambiguum, et Veneris monumenta nefandæ. Hinc merula in nigro se oblectat nigra marito, Hinc socium lasciva petit Philomela canorum, Agnoscitque pares sonitus, hinc Noctua tetram Canitiem alarum, et glaucos miratur ocellos. Nempe sibi semper constat, crescitque quotannis Lucida progenies, castos confessa parentes; Dum virides inter saltus lucosque sonoros Vere novo exultat, plumasque decora Juventus Explicat ad solem, patriisque coloribus ardet.ScitThe Latin poem is by Addison himself. The translation, by an unknown writer, comes from a 1744 edition of the Spectator."The feather'd Husband, to his partner true, Preserves connubial Rites inviolate. With cold Indifference every Charm he sees, The milky Whiteness of the stately Neck, The shining Down, proud Crest, and purple Wings: But cautious with a searching Eye explores The female Tribes, his proper Mate to find, With kindred Colours mark'd: Did he not so, The Grove with painted Monsters wou'd abound, Th'ambiguous Product of unnatural Love. The Black-bird hence selects her sooty Spouse: The Nightingale her musical Compeer, Lur'd by the well-known Voice: the Bird of Night, Smit with his dusky Wings, and greenish Eyes, Woos his dun Paramour. The beauteous Race Speak the chaste loves of their Progenitors; When, by the Spring invited, they exult In Woods and Fields, and to the Sun unfold Their Plumes, that with paternal Colours glow."

There is a second Kind of Beauty that we find in the several Products of Art and Nature, which does not work in the Imagination with that Warmth and Violence as the Beauty that appears in our proper Species, but is apt however to raise in us a secret Delight, and a kind of Fondness for the Places or Objects in which we discover it. This consists either in the Gaiety or Variety of Colours, in the Symmetry and Proportion of Parts, in the Arrangement and Disposition of Bodies, or in a just Mixture and Concurrence of all together. Among these several Kinds of Beauty the Eye takes most Delight in Colours. We no where meet with a more glorious or pleasing Show in Nature than what appears in the Heavens at the rising and setting of the Sun, which is wholly made up of those different Stains of Light that shew themselves in Clouds of a different Situation. For this Reason we find the Poets, who are always addressing themselves to the Imagination, borrowing more of their Epithets from Colours than from any other Topic. As the Fancy delights in every thing that is Great, Strange, or Beautiful, and is still more pleased the more it finds of these Perfections in the same Object, so is it capable of receiving a new Satisfaction by the Assistance of another Sense. Thus any continued Sound, as the Musick of Birds, or a Fall of Water, awakens every moment the Mind of the Beholder, and makes him more attentive to the several Beauties of the Place that lye before him. Thus if there arises a Fragrancy of Smells or Perfumes, they heighten the Pleasures of the Imagination, and make even the Colours and Verdure of the Landskip appear more agreeable; for the Ideas of both Senses recommend each other, and are pleasanter together than when they enter the Mind separately: As the different Colours of a Picture, when they are well disposed, set off one another, and receive an additional Beauty from the Advantage of their Situation.

O.OOAddison signed each issue of the journal that he wrote with either C, L, I, O, the letters spelling the name "Clio," the muse of history.