"To the Nightingale"

By

Anne Finch

Transcription, correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Students of Marymount University, James West, Amy Ridderhof

[titlepage]

POEMS

ON

Several Occasions, viz. .

[...] Written by the Right Honorable ANNE ,

Countess of Winchelsea author .

LONDON :

Printed by J. B. and sold by W. Taylor at the Ship

in Paternoster-Row , and Jonas Browne at the

Black Swan without Temple-bar . 1714 .

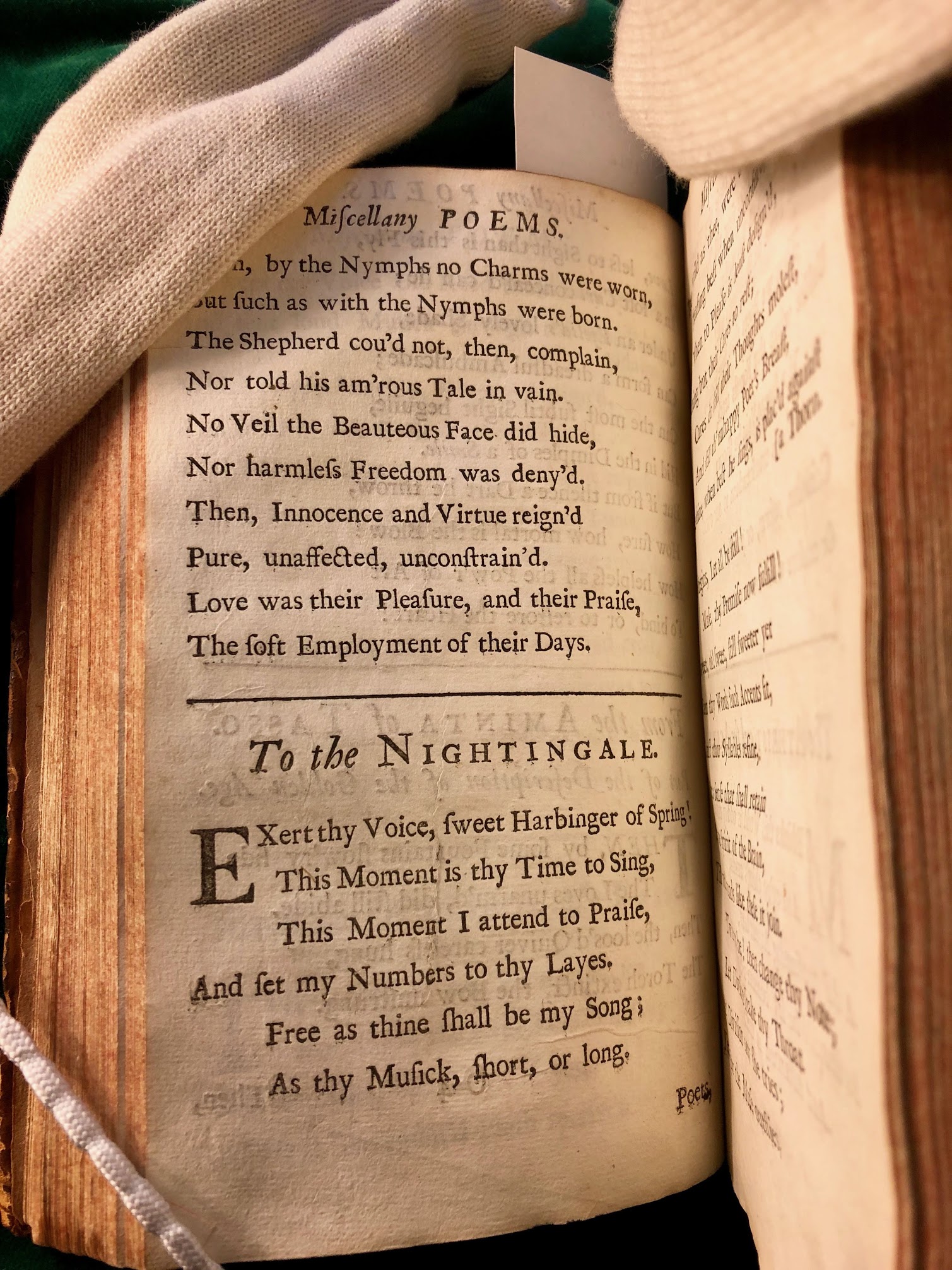

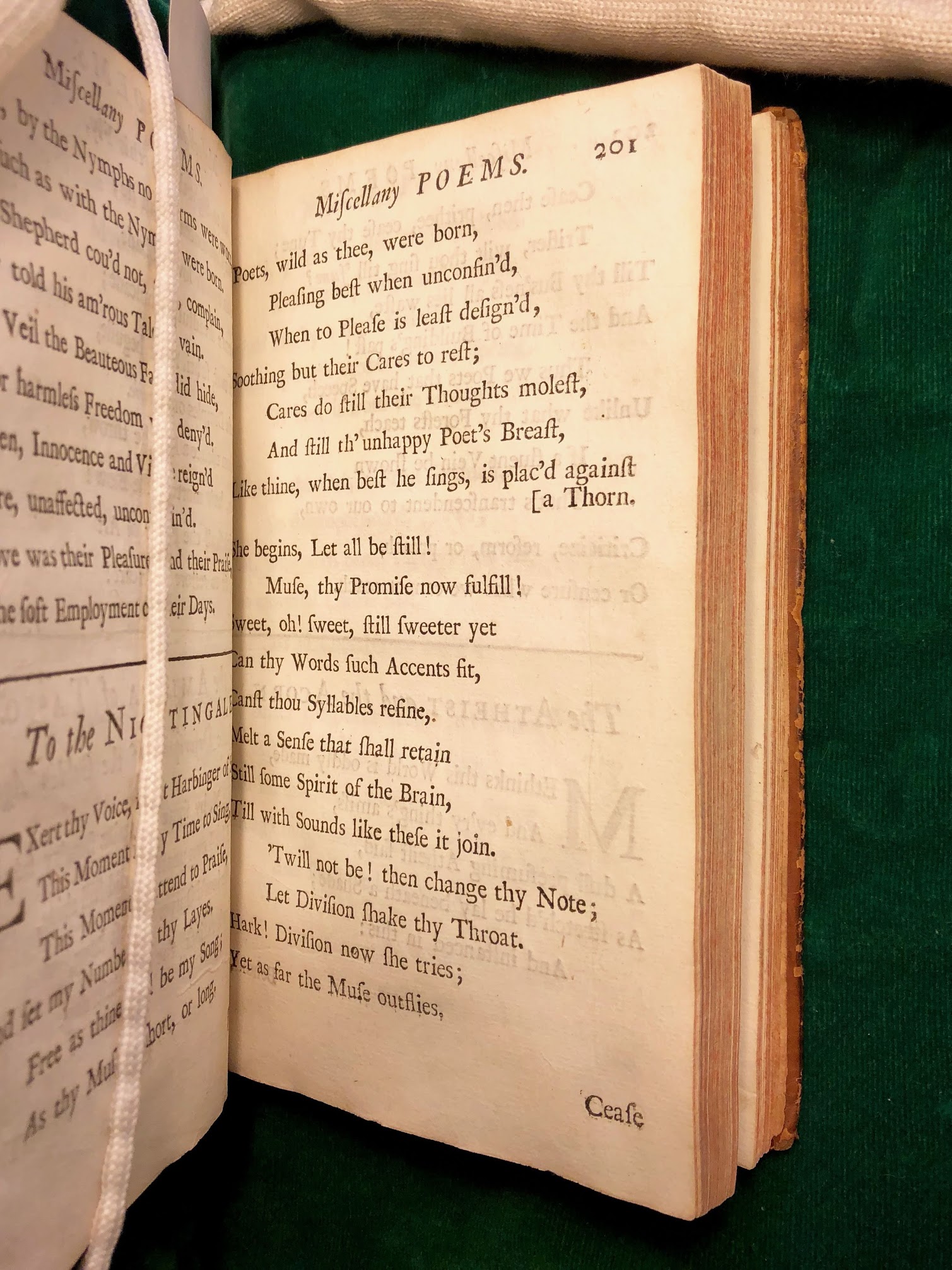

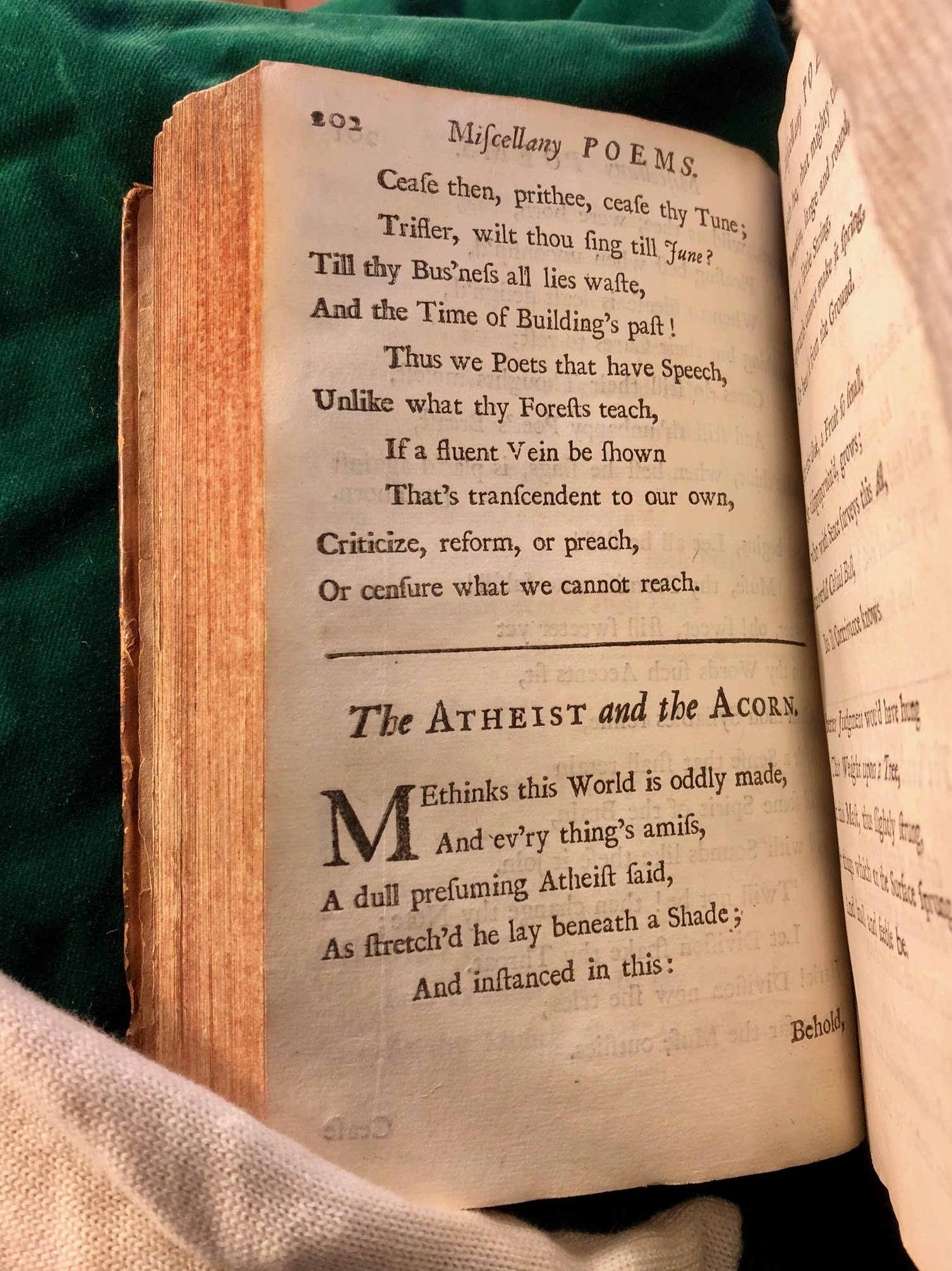

200 To the NIGHTINGALEnightingale . 1EXert thy Voice, Sweet Harbinger of Spring 2This Moment is thy Time to Sing, 3This Moment I attend to Praise, 4 And set my Numbersnumbers to thy Layeslays . 5Free as thine shall be my Song; 6As thy Musick, short, or long. 7Poets, wild as thee, were born, 201 8Pleasing best when unconfin'd, 9When to Please is least design'd, 10Soothing but their Cares to rest; 11Cares do still their Thoughts molest, 12And still th'unhappy Poet's Breast, 13Like thine, when best he sings, is plac'd against a Thorn. 14She begins, Let all be still! 15 Musemuse , thy Promise now fulfill! 16Sweet, oh! sweet, still sweeter yet 17Can thy Words such Accents fit, 18Canst thou Syllables refine, 19Melt a Sense that shall retain 20Still some Spirit of the Brain, 21Till with Sounds like these it join. 22‘Twill not be ! then change thy Note; 23 Let Divisiondivision shake thy Throat. 24Hark! Division now she tries; 25Yet as far the Muse outflies 202 26Cease then, prithee, cease thy Tune; 27 Trifler, wilt thou sing till June? 28Till thy Bus'ness all lies waste, 29And the Time of Building's past ! 30Thus we Poets that have Speech, 31Unlike what thy Forests teach, 32If a fluent Vein be shown 33That's transcendent to our own, 34Criticize, reform, or preach, 35Or censure what we cannot reach. author Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea,

was born in April 1661 to Anne Haselwood and Sir William Kingsmill. At age

twenty-one she was appointed maid of honor to Mary

Modena , the wife of the Duke of York, in the Court of Charles II.

During her time in the Court, Anne

Kingsmill was courted by and eventually married to Colonel Heneage

Finch. In 1689, after a shift in political power, the Finches faced monetary

problems and moved several times, eventually settling in Eastwell with their nephew.

As a woman writer in the Augustan era, Finch was also out of place. Barbara

McGovern's 2002 critical biography of Finch explores these

displacements both in her life and her poetry. Finch struggled, as McGovern

notes, to define her poetic identity in an era when women were excluded from

the conditions that would allow them to cultivate their minds or their

voices. The poet was seen as male, and publishing poetry, a masculine,

public activity; for a woman to do so was, in the Augustan period, risque

and licentious (See Katherine Rogers' essay, "Anne Finch, Countess of

Winchelsea: An Augustan Woman Writer," in Pacheco

227 ); Finch had to negotiate these competing cultural rules in

her poetry.

Finch's poetry from 1701-1714 was wide ranging. She wrote on subjects

typically allowed to be feminine, like her love for her husband, but she

also wrote about public and political issues, like the succession of power

in London. In 1701, Finch anonymously published "Upon the

Death of King James the Second" . Poems such as "The Spleen" and "All is Vanity" exemplify the idea of faith despite tribulation,

a subject she explored often. Prior to the 1713 publication of Miscellany Poems on Several Occasions , Finch

circulated private manuscripts of her poems and gained a favorable literary

reputation. For more information on women writers and manuscript

circulation, see George Justice's introduction to

Women's Writing and the Circulation of Ideas:

Manuscript Publication in England, 1550-1800

(2002) or Margaret Ezell's

Social Authorship and the Advent of Print

(1999).

Rogers

emphasizes Finch's Augustan roots, highlighting her use of form as

well as her love poetry, satirical prose, and ideas on the relationship

between man and nature (225). According to Rogers, Finch became one of the

few female authors in the Augustan era to successfully master the masculine

rules of the literary tradition. During the early modern period, women

"frequently found themselves denied opportunities for publication and

serious public reception, or had their writings denigrated and trivialized

by a patriarchal literary world" ( McGovern 2

)--as detailed in Finch's poem "The Introduction," which remained

unpublished during her lifetime. Finch was able to make her voice heard by

working within the masculine restraints of Augustan form.

Finch died on August 5, 1720. According to the

National

Poetry Foundation

the first recognized modern edition of her work was released in 1903.

Since the advent of feminist recovery criticism in the 1970s and 1980s, Anne

Finch has gained critical acclaim; she is now regarded as one of the most

important English women writers of the 18th century. The image to the right

shows a miniature watercolor portrait of Anne Finch by Peter Cross ,

housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

- [JW]

nightingale

Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea,

was born in April 1661 to Anne Haselwood and Sir William Kingsmill. At age

twenty-one she was appointed maid of honor to Mary

Modena , the wife of the Duke of York, in the Court of Charles II.

During her time in the Court, Anne

Kingsmill was courted by and eventually married to Colonel Heneage

Finch. In 1689, after a shift in political power, the Finches faced monetary

problems and moved several times, eventually settling in Eastwell with their nephew.

As a woman writer in the Augustan era, Finch was also out of place. Barbara

McGovern's 2002 critical biography of Finch explores these

displacements both in her life and her poetry. Finch struggled, as McGovern

notes, to define her poetic identity in an era when women were excluded from

the conditions that would allow them to cultivate their minds or their

voices. The poet was seen as male, and publishing poetry, a masculine,

public activity; for a woman to do so was, in the Augustan period, risque

and licentious (See Katherine Rogers' essay, "Anne Finch, Countess of

Winchelsea: An Augustan Woman Writer," in Pacheco

227 ); Finch had to negotiate these competing cultural rules in

her poetry.

Finch's poetry from 1701-1714 was wide ranging. She wrote on subjects

typically allowed to be feminine, like her love for her husband, but she

also wrote about public and political issues, like the succession of power

in London. In 1701, Finch anonymously published "Upon the

Death of King James the Second" . Poems such as "The Spleen" and "All is Vanity" exemplify the idea of faith despite tribulation,

a subject she explored often. Prior to the 1713 publication of Miscellany Poems on Several Occasions , Finch

circulated private manuscripts of her poems and gained a favorable literary

reputation. For more information on women writers and manuscript

circulation, see George Justice's introduction to

Women's Writing and the Circulation of Ideas:

Manuscript Publication in England, 1550-1800

(2002) or Margaret Ezell's

Social Authorship and the Advent of Print

(1999).

Rogers

emphasizes Finch's Augustan roots, highlighting her use of form as

well as her love poetry, satirical prose, and ideas on the relationship

between man and nature (225). According to Rogers, Finch became one of the

few female authors in the Augustan era to successfully master the masculine

rules of the literary tradition. During the early modern period, women

"frequently found themselves denied opportunities for publication and

serious public reception, or had their writings denigrated and trivialized

by a patriarchal literary world" ( McGovern 2

)--as detailed in Finch's poem "The Introduction," which remained

unpublished during her lifetime. Finch was able to make her voice heard by

working within the masculine restraints of Augustan form.

Finch died on August 5, 1720. According to the

National

Poetry Foundation

the first recognized modern edition of her work was released in 1903.

Since the advent of feminist recovery criticism in the 1970s and 1980s, Anne

Finch has gained critical acclaim; she is now regarded as one of the most

important English women writers of the 18th century. The image to the right

shows a miniature watercolor portrait of Anne Finch by Peter Cross ,

housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

- [JW]

nightingale

The nightingale is a small bird native

to Europe and Asia, with a population in the United Kingdom as well as Africa.

It is known for its beautiful, complex song, characterized by "a fast succession of high, low and rich notes that few other species can

match," and for that reason has long been associated with poets and

poetry,

as poet Edward Hirsch notes in his introduction to To a

Nightingale: Poems from Sappho to Borges. Often, the nightingale alludes to the classical myth of the rape of Philomela , whose

violation is ostensibly recompensed with an unearthly beautiful song. While the

nightingale is frequently invoked in lyric poetry as a feminized muse for the

masculine poet to draw inspiration from, as Charles Hinnant notes in

"Song and Speech in Anne Finch's ‘To the Nightingale,'" Finch recasts

the bird as an idealized muse for all poets, regardless of gender (504). This

poem, is a significant attempt on Finch's part "to master a recurrent problem

for the...female poet: how to participate in a discourse in which the poet is

defined as a masculine subject" (503). This video allows you to hear a

nightingale singing. The image to the right, via RSPB, shows the nightingale,

luscinia megarhynchos. - [TH]

numbers

"Numbers" refers to the metrical quality of poetic verse; it also metonymically signifies poetry in general. In Alexander Pope's "Epistle to Arbuthnot," he says that he "lisp'd in

numbers, for the numbers came" (128), suggesting that he spoke in poetic form

even as a child. Poetry is associated with music because of the metrical quality

of both. Finch's use of the word "set" in this line emphasizes musicality,

specifically the setting of words to music (see OED "set" v1, 73.a). - [TH]

lays

According to the

Encyclopedia Britanica

, a "Lay" refers to a song or story in song. Finch in this instance is

seeking to create a poem that mirrors the song of the Nightingale. - [JW]

muse According

to

A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology

, the Muses are "inspiring goddesses of song" who "presid[e] over the

different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and sciences." In this poem, Finch

positions the nightingale as her muse and rival. - [JW]

division

According to the

Encyclopedia Britannica entry on ornamentation, division refers to a technique, popular in early modern music theory,

characterized by dividing longer notes into a series of shorter note groupings.

This is an early form of improvisation. For more information, please see "simple meter

and time signatures" in the Open Music Theory textbook. - [JW]

The nightingale is a small bird native

to Europe and Asia, with a population in the United Kingdom as well as Africa.

It is known for its beautiful, complex song, characterized by "a fast succession of high, low and rich notes that few other species can

match," and for that reason has long been associated with poets and

poetry,

as poet Edward Hirsch notes in his introduction to To a

Nightingale: Poems from Sappho to Borges. Often, the nightingale alludes to the classical myth of the rape of Philomela , whose

violation is ostensibly recompensed with an unearthly beautiful song. While the

nightingale is frequently invoked in lyric poetry as a feminized muse for the

masculine poet to draw inspiration from, as Charles Hinnant notes in

"Song and Speech in Anne Finch's ‘To the Nightingale,'" Finch recasts

the bird as an idealized muse for all poets, regardless of gender (504). This

poem, is a significant attempt on Finch's part "to master a recurrent problem

for the...female poet: how to participate in a discourse in which the poet is

defined as a masculine subject" (503). This video allows you to hear a

nightingale singing. The image to the right, via RSPB, shows the nightingale,

luscinia megarhynchos. - [TH]

numbers

"Numbers" refers to the metrical quality of poetic verse; it also metonymically signifies poetry in general. In Alexander Pope's "Epistle to Arbuthnot," he says that he "lisp'd in

numbers, for the numbers came" (128), suggesting that he spoke in poetic form

even as a child. Poetry is associated with music because of the metrical quality

of both. Finch's use of the word "set" in this line emphasizes musicality,

specifically the setting of words to music (see OED "set" v1, 73.a). - [TH]

lays

According to the

Encyclopedia Britanica

, a "Lay" refers to a song or story in song. Finch in this instance is

seeking to create a poem that mirrors the song of the Nightingale. - [JW]

muse According

to

A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology

, the Muses are "inspiring goddesses of song" who "presid[e] over the

different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and sciences." In this poem, Finch

positions the nightingale as her muse and rival. - [JW]

division

According to the

Encyclopedia Britannica entry on ornamentation, division refers to a technique, popular in early modern music theory,

characterized by dividing longer notes into a series of shorter note groupings.

This is an early form of improvisation. For more information, please see "simple meter

and time signatures" in the Open Music Theory textbook. - [JW]

ON

Several Occasions, viz. .

[...] Written by the Right Honorable ANNE ,

Countess of Winchelsea author .

LONDON :

Printed by J. B. and sold by W. Taylor at the Ship

in Paternoster-Row , and Jonas Browne at the

Black Swan without Temple-bar . 1714 .

200 To the NIGHTINGALEnightingale . 1EXert thy Voice, Sweet Harbinger of Spring 2This Moment is thy Time to Sing, 3This Moment I attend to Praise, 4 And set my Numbersnumbers to thy Layeslays . 5Free as thine shall be my Song; 6As thy Musick, short, or long. 7Poets, wild as thee, were born, 201 8Pleasing best when unconfin'd, 9When to Please is least design'd, 10Soothing but their Cares to rest; 11Cares do still their Thoughts molest, 12And still th'unhappy Poet's Breast, 13Like thine, when best he sings, is plac'd against a Thorn. 14She begins, Let all be still! 15 Musemuse , thy Promise now fulfill! 16Sweet, oh! sweet, still sweeter yet 17Can thy Words such Accents fit, 18Canst thou Syllables refine, 19Melt a Sense that shall retain 20Still some Spirit of the Brain, 21Till with Sounds like these it join. 22‘Twill not be ! then change thy Note; 23 Let Divisiondivision shake thy Throat. 24Hark! Division now she tries; 25Yet as far the Muse outflies 202 26Cease then, prithee, cease thy Tune; 27 Trifler, wilt thou sing till June? 28Till thy Bus'ness all lies waste, 29And the Time of Building's past ! 30Thus we Poets that have Speech, 31Unlike what thy Forests teach, 32If a fluent Vein be shown 33That's transcendent to our own, 34Criticize, reform, or preach, 35Or censure what we cannot reach. author

Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea,

was born in April 1661 to Anne Haselwood and Sir William Kingsmill. At age

twenty-one she was appointed maid of honor to Mary

Modena , the wife of the Duke of York, in the Court of Charles II.

During her time in the Court, Anne

Kingsmill was courted by and eventually married to Colonel Heneage

Finch. In 1689, after a shift in political power, the Finches faced monetary

problems and moved several times, eventually settling in Eastwell with their nephew.

As a woman writer in the Augustan era, Finch was also out of place. Barbara

McGovern's 2002 critical biography of Finch explores these

displacements both in her life and her poetry. Finch struggled, as McGovern

notes, to define her poetic identity in an era when women were excluded from

the conditions that would allow them to cultivate their minds or their

voices. The poet was seen as male, and publishing poetry, a masculine,

public activity; for a woman to do so was, in the Augustan period, risque

and licentious (See Katherine Rogers' essay, "Anne Finch, Countess of

Winchelsea: An Augustan Woman Writer," in Pacheco

227 ); Finch had to negotiate these competing cultural rules in

her poetry.

Finch's poetry from 1701-1714 was wide ranging. She wrote on subjects

typically allowed to be feminine, like her love for her husband, but she

also wrote about public and political issues, like the succession of power

in London. In 1701, Finch anonymously published "Upon the

Death of King James the Second" . Poems such as "The Spleen" and "All is Vanity" exemplify the idea of faith despite tribulation,

a subject she explored often. Prior to the 1713 publication of Miscellany Poems on Several Occasions , Finch

circulated private manuscripts of her poems and gained a favorable literary

reputation. For more information on women writers and manuscript

circulation, see George Justice's introduction to

Women's Writing and the Circulation of Ideas:

Manuscript Publication in England, 1550-1800

(2002) or Margaret Ezell's

Social Authorship and the Advent of Print

(1999).

Rogers

emphasizes Finch's Augustan roots, highlighting her use of form as

well as her love poetry, satirical prose, and ideas on the relationship

between man and nature (225). According to Rogers, Finch became one of the

few female authors in the Augustan era to successfully master the masculine

rules of the literary tradition. During the early modern period, women

"frequently found themselves denied opportunities for publication and

serious public reception, or had their writings denigrated and trivialized

by a patriarchal literary world" ( McGovern 2

)--as detailed in Finch's poem "The Introduction," which remained

unpublished during her lifetime. Finch was able to make her voice heard by

working within the masculine restraints of Augustan form.

Finch died on August 5, 1720. According to the

National

Poetry Foundation

the first recognized modern edition of her work was released in 1903.

Since the advent of feminist recovery criticism in the 1970s and 1980s, Anne

Finch has gained critical acclaim; she is now regarded as one of the most

important English women writers of the 18th century. The image to the right

shows a miniature watercolor portrait of Anne Finch by Peter Cross ,

housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

- [JW]

nightingale

Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea,

was born in April 1661 to Anne Haselwood and Sir William Kingsmill. At age

twenty-one she was appointed maid of honor to Mary

Modena , the wife of the Duke of York, in the Court of Charles II.

During her time in the Court, Anne

Kingsmill was courted by and eventually married to Colonel Heneage

Finch. In 1689, after a shift in political power, the Finches faced monetary

problems and moved several times, eventually settling in Eastwell with their nephew.

As a woman writer in the Augustan era, Finch was also out of place. Barbara

McGovern's 2002 critical biography of Finch explores these

displacements both in her life and her poetry. Finch struggled, as McGovern

notes, to define her poetic identity in an era when women were excluded from

the conditions that would allow them to cultivate their minds or their

voices. The poet was seen as male, and publishing poetry, a masculine,

public activity; for a woman to do so was, in the Augustan period, risque

and licentious (See Katherine Rogers' essay, "Anne Finch, Countess of

Winchelsea: An Augustan Woman Writer," in Pacheco

227 ); Finch had to negotiate these competing cultural rules in

her poetry.

Finch's poetry from 1701-1714 was wide ranging. She wrote on subjects

typically allowed to be feminine, like her love for her husband, but she

also wrote about public and political issues, like the succession of power

in London. In 1701, Finch anonymously published "Upon the

Death of King James the Second" . Poems such as "The Spleen" and "All is Vanity" exemplify the idea of faith despite tribulation,

a subject she explored often. Prior to the 1713 publication of Miscellany Poems on Several Occasions , Finch

circulated private manuscripts of her poems and gained a favorable literary

reputation. For more information on women writers and manuscript

circulation, see George Justice's introduction to

Women's Writing and the Circulation of Ideas:

Manuscript Publication in England, 1550-1800

(2002) or Margaret Ezell's

Social Authorship and the Advent of Print

(1999).

Rogers

emphasizes Finch's Augustan roots, highlighting her use of form as

well as her love poetry, satirical prose, and ideas on the relationship

between man and nature (225). According to Rogers, Finch became one of the

few female authors in the Augustan era to successfully master the masculine

rules of the literary tradition. During the early modern period, women

"frequently found themselves denied opportunities for publication and

serious public reception, or had their writings denigrated and trivialized

by a patriarchal literary world" ( McGovern 2

)--as detailed in Finch's poem "The Introduction," which remained

unpublished during her lifetime. Finch was able to make her voice heard by

working within the masculine restraints of Augustan form.

Finch died on August 5, 1720. According to the

National

Poetry Foundation

the first recognized modern edition of her work was released in 1903.

Since the advent of feminist recovery criticism in the 1970s and 1980s, Anne

Finch has gained critical acclaim; she is now regarded as one of the most

important English women writers of the 18th century. The image to the right

shows a miniature watercolor portrait of Anne Finch by Peter Cross ,

housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

- [JW]

nightingale

The nightingale is a small bird native

to Europe and Asia, with a population in the United Kingdom as well as Africa.

It is known for its beautiful, complex song, characterized by "a fast succession of high, low and rich notes that few other species can

match," and for that reason has long been associated with poets and

poetry,

as poet Edward Hirsch notes in his introduction to To a

Nightingale: Poems from Sappho to Borges. Often, the nightingale alludes to the classical myth of the rape of Philomela , whose

violation is ostensibly recompensed with an unearthly beautiful song. While the

nightingale is frequently invoked in lyric poetry as a feminized muse for the

masculine poet to draw inspiration from, as Charles Hinnant notes in

"Song and Speech in Anne Finch's ‘To the Nightingale,'" Finch recasts

the bird as an idealized muse for all poets, regardless of gender (504). This

poem, is a significant attempt on Finch's part "to master a recurrent problem

for the...female poet: how to participate in a discourse in which the poet is

defined as a masculine subject" (503). This video allows you to hear a

nightingale singing. The image to the right, via RSPB, shows the nightingale,

luscinia megarhynchos. - [TH]

numbers

"Numbers" refers to the metrical quality of poetic verse; it also metonymically signifies poetry in general. In Alexander Pope's "Epistle to Arbuthnot," he says that he "lisp'd in

numbers, for the numbers came" (128), suggesting that he spoke in poetic form

even as a child. Poetry is associated with music because of the metrical quality

of both. Finch's use of the word "set" in this line emphasizes musicality,

specifically the setting of words to music (see OED "set" v1, 73.a). - [TH]

lays

According to the

Encyclopedia Britanica

, a "Lay" refers to a song or story in song. Finch in this instance is

seeking to create a poem that mirrors the song of the Nightingale. - [JW]

muse According

to

A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology

, the Muses are "inspiring goddesses of song" who "presid[e] over the

different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and sciences." In this poem, Finch

positions the nightingale as her muse and rival. - [JW]

division

According to the

Encyclopedia Britannica entry on ornamentation, division refers to a technique, popular in early modern music theory,

characterized by dividing longer notes into a series of shorter note groupings.

This is an early form of improvisation. For more information, please see "simple meter

and time signatures" in the Open Music Theory textbook. - [JW]

The nightingale is a small bird native

to Europe and Asia, with a population in the United Kingdom as well as Africa.

It is known for its beautiful, complex song, characterized by "a fast succession of high, low and rich notes that few other species can

match," and for that reason has long been associated with poets and

poetry,

as poet Edward Hirsch notes in his introduction to To a

Nightingale: Poems from Sappho to Borges. Often, the nightingale alludes to the classical myth of the rape of Philomela , whose

violation is ostensibly recompensed with an unearthly beautiful song. While the

nightingale is frequently invoked in lyric poetry as a feminized muse for the

masculine poet to draw inspiration from, as Charles Hinnant notes in

"Song and Speech in Anne Finch's ‘To the Nightingale,'" Finch recasts

the bird as an idealized muse for all poets, regardless of gender (504). This

poem, is a significant attempt on Finch's part "to master a recurrent problem

for the...female poet: how to participate in a discourse in which the poet is

defined as a masculine subject" (503). This video allows you to hear a

nightingale singing. The image to the right, via RSPB, shows the nightingale,

luscinia megarhynchos. - [TH]

numbers

"Numbers" refers to the metrical quality of poetic verse; it also metonymically signifies poetry in general. In Alexander Pope's "Epistle to Arbuthnot," he says that he "lisp'd in

numbers, for the numbers came" (128), suggesting that he spoke in poetic form

even as a child. Poetry is associated with music because of the metrical quality

of both. Finch's use of the word "set" in this line emphasizes musicality,

specifically the setting of words to music (see OED "set" v1, 73.a). - [TH]

lays

According to the

Encyclopedia Britanica

, a "Lay" refers to a song or story in song. Finch in this instance is

seeking to create a poem that mirrors the song of the Nightingale. - [JW]

muse According

to

A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology

, the Muses are "inspiring goddesses of song" who "presid[e] over the

different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and sciences." In this poem, Finch

positions the nightingale as her muse and rival. - [JW]

division

According to the

Encyclopedia Britannica entry on ornamentation, division refers to a technique, popular in early modern music theory,

characterized by dividing longer notes into a series of shorter note groupings.

This is an early form of improvisation. For more information, please see "simple meter

and time signatures" in the Open Music Theory textbook. - [JW]

Footnotes

author_

Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea,

was born in April 1661 to Anne Haselwood and Sir William Kingsmill. At age

twenty-one she was appointed maid of honor to Mary

Modena , the wife of the Duke of York, in the Court of Charles II.

During her time in the Court, Anne

Kingsmill was courted by and eventually married to Colonel Heneage

Finch. In 1689, after a shift in political power, the Finches faced monetary

problems and moved several times, eventually settling in Eastwell with their nephew.

As a woman writer in the Augustan era, Finch was also out of place. Barbara

McGovern's 2002 critical biography of Finch explores these

displacements both in her life and her poetry. Finch struggled, as McGovern

notes, to define her poetic identity in an era when women were excluded from

the conditions that would allow them to cultivate their minds or their

voices. The poet was seen as male, and publishing poetry, a masculine,

public activity; for a woman to do so was, in the Augustan period, risque

and licentious (See Katherine Rogers' essay, "Anne Finch, Countess of

Winchelsea: An Augustan Woman Writer," in Pacheco

227 ); Finch had to negotiate these competing cultural rules in

her poetry.

Finch's poetry from 1701-1714 was wide ranging. She wrote on subjects

typically allowed to be feminine, like her love for her husband, but she

also wrote about public and political issues, like the succession of power

in London. In 1701, Finch anonymously published "Upon the

Death of King James the Second" . Poems such as "The Spleen" and "All is Vanity" exemplify the idea of faith despite tribulation,

a subject she explored often. Prior to the 1713 publication of Miscellany Poems on Several Occasions , Finch

circulated private manuscripts of her poems and gained a favorable literary

reputation. For more information on women writers and manuscript

circulation, see George Justice's introduction to

Women's Writing and the Circulation of Ideas:

Manuscript Publication in England, 1550-1800

(2002) or Margaret Ezell's

Social Authorship and the Advent of Print

(1999).

Rogers

emphasizes Finch's Augustan roots, highlighting her use of form as

well as her love poetry, satirical prose, and ideas on the relationship

between man and nature (225). According to Rogers, Finch became one of the

few female authors in the Augustan era to successfully master the masculine

rules of the literary tradition. During the early modern period, women

"frequently found themselves denied opportunities for publication and

serious public reception, or had their writings denigrated and trivialized

by a patriarchal literary world" ( McGovern 2

)--as detailed in Finch's poem "The Introduction," which remained

unpublished during her lifetime. Finch was able to make her voice heard by

working within the masculine restraints of Augustan form.

Finch died on August 5, 1720. According to the

National

Poetry Foundation

the first recognized modern edition of her work was released in 1903.

Since the advent of feminist recovery criticism in the 1970s and 1980s, Anne

Finch has gained critical acclaim; she is now regarded as one of the most

important English women writers of the 18th century. The image to the right

shows a miniature watercolor portrait of Anne Finch by Peter Cross ,

housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea,

was born in April 1661 to Anne Haselwood and Sir William Kingsmill. At age

twenty-one she was appointed maid of honor to Mary

Modena , the wife of the Duke of York, in the Court of Charles II.

During her time in the Court, Anne

Kingsmill was courted by and eventually married to Colonel Heneage

Finch. In 1689, after a shift in political power, the Finches faced monetary

problems and moved several times, eventually settling in Eastwell with their nephew.

As a woman writer in the Augustan era, Finch was also out of place. Barbara

McGovern's 2002 critical biography of Finch explores these

displacements both in her life and her poetry. Finch struggled, as McGovern

notes, to define her poetic identity in an era when women were excluded from

the conditions that would allow them to cultivate their minds or their

voices. The poet was seen as male, and publishing poetry, a masculine,

public activity; for a woman to do so was, in the Augustan period, risque

and licentious (See Katherine Rogers' essay, "Anne Finch, Countess of

Winchelsea: An Augustan Woman Writer," in Pacheco

227 ); Finch had to negotiate these competing cultural rules in

her poetry.

Finch's poetry from 1701-1714 was wide ranging. She wrote on subjects

typically allowed to be feminine, like her love for her husband, but she

also wrote about public and political issues, like the succession of power

in London. In 1701, Finch anonymously published "Upon the

Death of King James the Second" . Poems such as "The Spleen" and "All is Vanity" exemplify the idea of faith despite tribulation,

a subject she explored often. Prior to the 1713 publication of Miscellany Poems on Several Occasions , Finch

circulated private manuscripts of her poems and gained a favorable literary

reputation. For more information on women writers and manuscript

circulation, see George Justice's introduction to

Women's Writing and the Circulation of Ideas:

Manuscript Publication in England, 1550-1800

(2002) or Margaret Ezell's

Social Authorship and the Advent of Print

(1999).

Rogers

emphasizes Finch's Augustan roots, highlighting her use of form as

well as her love poetry, satirical prose, and ideas on the relationship

between man and nature (225). According to Rogers, Finch became one of the

few female authors in the Augustan era to successfully master the masculine

rules of the literary tradition. During the early modern period, women

"frequently found themselves denied opportunities for publication and

serious public reception, or had their writings denigrated and trivialized

by a patriarchal literary world" ( McGovern 2

)--as detailed in Finch's poem "The Introduction," which remained

unpublished during her lifetime. Finch was able to make her voice heard by

working within the masculine restraints of Augustan form.

Finch died on August 5, 1720. According to the

National

Poetry Foundation

the first recognized modern edition of her work was released in 1903.

Since the advent of feminist recovery criticism in the 1970s and 1980s, Anne

Finch has gained critical acclaim; she is now regarded as one of the most

important English women writers of the 18th century. The image to the right

shows a miniature watercolor portrait of Anne Finch by Peter Cross ,

housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea,

was born in April 1661 to Anne Haselwood and Sir William Kingsmill. At age

twenty-one she was appointed maid of honor to Mary

Modena , the wife of the Duke of York, in the Court of Charles II.

During her time in the Court, Anne

Kingsmill was courted by and eventually married to Colonel Heneage

Finch. In 1689, after a shift in political power, the Finches faced monetary

problems and moved several times, eventually settling in Eastwell with their nephew.

As a woman writer in the Augustan era, Finch was also out of place. Barbara

McGovern's 2002 critical biography of Finch explores these

displacements both in her life and her poetry. Finch struggled, as McGovern

notes, to define her poetic identity in an era when women were excluded from

the conditions that would allow them to cultivate their minds or their

voices. The poet was seen as male, and publishing poetry, a masculine,

public activity; for a woman to do so was, in the Augustan period, risque

and licentious (See Katherine Rogers' essay, "Anne Finch, Countess of

Winchelsea: An Augustan Woman Writer," in Pacheco

227 ); Finch had to negotiate these competing cultural rules in

her poetry.

Finch's poetry from 1701-1714 was wide ranging. She wrote on subjects

typically allowed to be feminine, like her love for her husband, but she

also wrote about public and political issues, like the succession of power

in London. In 1701, Finch anonymously published "Upon the

Death of King James the Second" . Poems such as "The Spleen" and "All is Vanity" exemplify the idea of faith despite tribulation,

a subject she explored often. Prior to the 1713 publication of Miscellany Poems on Several Occasions , Finch

circulated private manuscripts of her poems and gained a favorable literary

reputation. For more information on women writers and manuscript

circulation, see George Justice's introduction to

Women's Writing and the Circulation of Ideas:

Manuscript Publication in England, 1550-1800

(2002) or Margaret Ezell's

Social Authorship and the Advent of Print

(1999).

Rogers

emphasizes Finch's Augustan roots, highlighting her use of form as

well as her love poetry, satirical prose, and ideas on the relationship

between man and nature (225). According to Rogers, Finch became one of the

few female authors in the Augustan era to successfully master the masculine

rules of the literary tradition. During the early modern period, women

"frequently found themselves denied opportunities for publication and

serious public reception, or had their writings denigrated and trivialized

by a patriarchal literary world" ( McGovern 2

)--as detailed in Finch's poem "The Introduction," which remained

unpublished during her lifetime. Finch was able to make her voice heard by

working within the masculine restraints of Augustan form.

Finch died on August 5, 1720. According to the

National

Poetry Foundation

the first recognized modern edition of her work was released in 1903.

Since the advent of feminist recovery criticism in the 1970s and 1980s, Anne

Finch has gained critical acclaim; she is now regarded as one of the most

important English women writers of the 18th century. The image to the right

shows a miniature watercolor portrait of Anne Finch by Peter Cross ,

housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea,

was born in April 1661 to Anne Haselwood and Sir William Kingsmill. At age

twenty-one she was appointed maid of honor to Mary

Modena , the wife of the Duke of York, in the Court of Charles II.

During her time in the Court, Anne

Kingsmill was courted by and eventually married to Colonel Heneage

Finch. In 1689, after a shift in political power, the Finches faced monetary

problems and moved several times, eventually settling in Eastwell with their nephew.

As a woman writer in the Augustan era, Finch was also out of place. Barbara

McGovern's 2002 critical biography of Finch explores these

displacements both in her life and her poetry. Finch struggled, as McGovern

notes, to define her poetic identity in an era when women were excluded from

the conditions that would allow them to cultivate their minds or their

voices. The poet was seen as male, and publishing poetry, a masculine,

public activity; for a woman to do so was, in the Augustan period, risque

and licentious (See Katherine Rogers' essay, "Anne Finch, Countess of

Winchelsea: An Augustan Woman Writer," in Pacheco

227 ); Finch had to negotiate these competing cultural rules in

her poetry.

Finch's poetry from 1701-1714 was wide ranging. She wrote on subjects

typically allowed to be feminine, like her love for her husband, but she

also wrote about public and political issues, like the succession of power

in London. In 1701, Finch anonymously published "Upon the

Death of King James the Second" . Poems such as "The Spleen" and "All is Vanity" exemplify the idea of faith despite tribulation,

a subject she explored often. Prior to the 1713 publication of Miscellany Poems on Several Occasions , Finch

circulated private manuscripts of her poems and gained a favorable literary

reputation. For more information on women writers and manuscript

circulation, see George Justice's introduction to

Women's Writing and the Circulation of Ideas:

Manuscript Publication in England, 1550-1800

(2002) or Margaret Ezell's

Social Authorship and the Advent of Print

(1999).

Rogers

emphasizes Finch's Augustan roots, highlighting her use of form as

well as her love poetry, satirical prose, and ideas on the relationship

between man and nature (225). According to Rogers, Finch became one of the

few female authors in the Augustan era to successfully master the masculine

rules of the literary tradition. During the early modern period, women

"frequently found themselves denied opportunities for publication and

serious public reception, or had their writings denigrated and trivialized

by a patriarchal literary world" ( McGovern 2

)--as detailed in Finch's poem "The Introduction," which remained

unpublished during her lifetime. Finch was able to make her voice heard by

working within the masculine restraints of Augustan form.

Finch died on August 5, 1720. According to the

National

Poetry Foundation

the first recognized modern edition of her work was released in 1903.

Since the advent of feminist recovery criticism in the 1970s and 1980s, Anne

Finch has gained critical acclaim; she is now regarded as one of the most

important English women writers of the 18th century. The image to the right

shows a miniature watercolor portrait of Anne Finch by Peter Cross ,

housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

nightingale_

The nightingale is a small bird native

to Europe and Asia, with a population in the United Kingdom as well as Africa.

It is known for its beautiful, complex song, characterized by "a fast succession of high, low and rich notes that few other species can

match," and for that reason has long been associated with poets and

poetry,

as poet Edward Hirsch notes in his introduction to To a

Nightingale: Poems from Sappho to Borges. Often, the nightingale alludes to the classical myth of the rape of Philomela , whose

violation is ostensibly recompensed with an unearthly beautiful song. While the

nightingale is frequently invoked in lyric poetry as a feminized muse for the

masculine poet to draw inspiration from, as Charles Hinnant notes in

"Song and Speech in Anne Finch's ‘To the Nightingale,'" Finch recasts

the bird as an idealized muse for all poets, regardless of gender (504). This

poem, is a significant attempt on Finch's part "to master a recurrent problem

for the...female poet: how to participate in a discourse in which the poet is

defined as a masculine subject" (503). This video allows you to hear a

nightingale singing. The image to the right, via RSPB, shows the nightingale,

luscinia megarhynchos.

The nightingale is a small bird native

to Europe and Asia, with a population in the United Kingdom as well as Africa.

It is known for its beautiful, complex song, characterized by "a fast succession of high, low and rich notes that few other species can

match," and for that reason has long been associated with poets and

poetry,

as poet Edward Hirsch notes in his introduction to To a

Nightingale: Poems from Sappho to Borges. Often, the nightingale alludes to the classical myth of the rape of Philomela , whose

violation is ostensibly recompensed with an unearthly beautiful song. While the

nightingale is frequently invoked in lyric poetry as a feminized muse for the

masculine poet to draw inspiration from, as Charles Hinnant notes in

"Song and Speech in Anne Finch's ‘To the Nightingale,'" Finch recasts

the bird as an idealized muse for all poets, regardless of gender (504). This

poem, is a significant attempt on Finch's part "to master a recurrent problem

for the...female poet: how to participate in a discourse in which the poet is

defined as a masculine subject" (503). This video allows you to hear a

nightingale singing. The image to the right, via RSPB, shows the nightingale,

luscinia megarhynchos.

The nightingale is a small bird native

to Europe and Asia, with a population in the United Kingdom as well as Africa.

It is known for its beautiful, complex song, characterized by "a fast succession of high, low and rich notes that few other species can

match," and for that reason has long been associated with poets and

poetry,

as poet Edward Hirsch notes in his introduction to To a

Nightingale: Poems from Sappho to Borges. Often, the nightingale alludes to the classical myth of the rape of Philomela , whose

violation is ostensibly recompensed with an unearthly beautiful song. While the

nightingale is frequently invoked in lyric poetry as a feminized muse for the

masculine poet to draw inspiration from, as Charles Hinnant notes in

"Song and Speech in Anne Finch's ‘To the Nightingale,'" Finch recasts

the bird as an idealized muse for all poets, regardless of gender (504). This

poem, is a significant attempt on Finch's part "to master a recurrent problem

for the...female poet: how to participate in a discourse in which the poet is

defined as a masculine subject" (503). This video allows you to hear a

nightingale singing. The image to the right, via RSPB, shows the nightingale,

luscinia megarhynchos.

The nightingale is a small bird native

to Europe and Asia, with a population in the United Kingdom as well as Africa.

It is known for its beautiful, complex song, characterized by "a fast succession of high, low and rich notes that few other species can

match," and for that reason has long been associated with poets and

poetry,

as poet Edward Hirsch notes in his introduction to To a

Nightingale: Poems from Sappho to Borges. Often, the nightingale alludes to the classical myth of the rape of Philomela , whose

violation is ostensibly recompensed with an unearthly beautiful song. While the

nightingale is frequently invoked in lyric poetry as a feminized muse for the

masculine poet to draw inspiration from, as Charles Hinnant notes in

"Song and Speech in Anne Finch's ‘To the Nightingale,'" Finch recasts

the bird as an idealized muse for all poets, regardless of gender (504). This

poem, is a significant attempt on Finch's part "to master a recurrent problem

for the...female poet: how to participate in a discourse in which the poet is

defined as a masculine subject" (503). This video allows you to hear a

nightingale singing. The image to the right, via RSPB, shows the nightingale,

luscinia megarhynchos. numbers_

"Numbers" refers to the metrical quality of poetic verse; it also metonymically signifies poetry in general. In Alexander Pope's "Epistle to Arbuthnot," he says that he "lisp'd in

numbers, for the numbers came" (128), suggesting that he spoke in poetic form

even as a child. Poetry is associated with music because of the metrical quality

of both. Finch's use of the word "set" in this line emphasizes musicality,

specifically the setting of words to music (see OED "set" v1, 73.a).

lays_

According to the

Encyclopedia Britanica

, a "Lay" refers to a song or story in song. Finch in this instance is

seeking to create a poem that mirrors the song of the Nightingale.

muse_ According

to

A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and

Mythology

, the Muses are "inspiring goddesses of song" who "presid[e] over the

different kinds of poetry, and over the arts and sciences." In this poem, Finch

positions the nightingale as her muse and rival.

division_

According to the

Encyclopedia Britannica entry on ornamentation, division refers to a technique, popular in early modern music theory,

characterized by dividing longer notes into a series of shorter note groupings.

This is an early form of improvisation. For more information, please see "simple meter

and time signatures" in the Open Music Theory textbook.

![Page [titlepage]](https://anthologyassetsdev.lib.virginia.edu/finch-nightingale/pageImages/199.jpg)