Northanger Abbey

By

Jane Austen

Correction, editorial commentary, and subsequent markup for this edition by Students and Staff of The University of Virginia

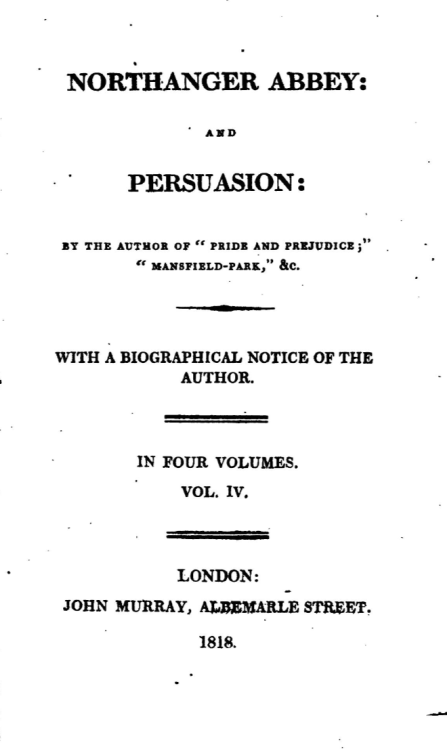

TitleNorthanger Abbey is both Jane Austen’s first and her last novel. We know that she wrote a draft of the book under the title Susan in the 1790s, and reached agreement with the London publisher Benjamin Crosby to sell the copyright to him for £10 in 1803. But Crosby sat on the manuscript for years, which seems to have frustrated Austen. In 1816, she was finally able to purchase the copyright back from him, and it seems that she did some revisions on the text, the most obvious of which was changing the name of the heroine from Susan to Catherine (a novel with the title Susan had come out in the meantime). But Austen was already sick by this point with what would be her final illness; she died on July 18, 1817, leaving this and the manuscript for the novel that became known as Persuasion in manuscript. Austen’s brother Henry and her sister Cassandra gave the two novels their titles, and Henry, who had often been Austen's intermediary with London publishers, arranged for them to be published together. The two novels, in a set of four small volumes, two for each of them, were published in late 1817, with an official publication year of 1818.

It is easy to see why Austen might have been frustrated with Crosby (who never explained his reasoning) for dragging his heels on publishing Susan, because the book is in part responding to the boom for Gothic fiction that took place in the 1780s and 1790s. There were scores of such works published in those decades, and many of them are referred to in the course of Northanger Abbey: The Castle of Wolfenbach by Eliza Parsons, Clermont by Regina Roche, The Necromancer by Lawrence Flammenberg and others. But above all, Austen and her heroine Catherine Morland refer to the works of Ann Radcliffe, one of the most popular writers of the entire period. Radcliffe’s gothic fictions such as The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797) were enormously popular in the period and remain enjoyable today. Northanger Abbey is in part a satire on these books, but it is also clear that Austen, like her heroine Catherine Morland, loved Radcliffe’s gothic novels. As much as anything else, Northanger Abbey is testimony to the power of novels, and of reading in general. Catherine Morland comes to learn that gothic novels are not a particularly good guide to how the real world works, but reading novels has also helped make her imaginative and empathetic, one of the most appealing of all of Austen’s heroines. If anything, Catherine needs to read more novels, novels perhaps like those by Austen herself. two_good_livingsThat is, Richard Morland receives income from his work as the pastor of two different parishes in the Church of England. Clergymen in the Church in this period would be granted a "living," sometimes also called a "benefice," to support themselves, and most such livings, which guaranteed an annual income that varied on the size and wealth of the area, would be associated with a particular parish. In most cases, this money would have come from the hierarchy of the Church of England, but was also sometimes in the gift of the most powerful local landowner in a given area. A clergyman generally held such a living or livings until he retired or died. As Richard Morland does, a successful clergyman could hold more than two livings at one time--usually in adjacent or nearby parishes--and thereby enhance his income. If a clergyman had more than one living, he might hire a younger, less well-established minister to be his "curate," performing some of the duties in one parish while he was doing his responsibilities in the other.herselfThe jokey tone of the phrase "as any body might expect," reminds the reader of how typical it was for mothers of heroines in novels to have died in childbirth by the time the story began. But the joke also reminds us of the grim reality that maternal mortality was quite high in this period, so that for Mrs. Morland to have survived childbirth ten times and to remain in "excellent health" was no small accomplishment.GrayThomas Gray, author "Elegy Written a Country Churchyard," quoted here.Bath

It is easy to see why Austen might have been frustrated with Crosby (who never explained his reasoning) for dragging his heels on publishing Susan, because the book is in part responding to the boom for Gothic fiction that took place in the 1780s and 1790s. There were scores of such works published in those decades, and many of them are referred to in the course of Northanger Abbey: The Castle of Wolfenbach by Eliza Parsons, Clermont by Regina Roche, The Necromancer by Lawrence Flammenberg and others. But above all, Austen and her heroine Catherine Morland refer to the works of Ann Radcliffe, one of the most popular writers of the entire period. Radcliffe’s gothic fictions such as The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797) were enormously popular in the period and remain enjoyable today. Northanger Abbey is in part a satire on these books, but it is also clear that Austen, like her heroine Catherine Morland, loved Radcliffe’s gothic novels. As much as anything else, Northanger Abbey is testimony to the power of novels, and of reading in general. Catherine Morland comes to learn that gothic novels are not a particularly good guide to how the real world works, but reading novels has also helped make her imaginative and empathetic, one of the most appealing of all of Austen’s heroines. If anything, Catherine needs to read more novels, novels perhaps like those by Austen herself. two_good_livingsThat is, Richard Morland receives income from his work as the pastor of two different parishes in the Church of England. Clergymen in the Church in this period would be granted a "living," sometimes also called a "benefice," to support themselves, and most such livings, which guaranteed an annual income that varied on the size and wealth of the area, would be associated with a particular parish. In most cases, this money would have come from the hierarchy of the Church of England, but was also sometimes in the gift of the most powerful local landowner in a given area. A clergyman generally held such a living or livings until he retired or died. As Richard Morland does, a successful clergyman could hold more than two livings at one time--usually in adjacent or nearby parishes--and thereby enhance his income. If a clergyman had more than one living, he might hire a younger, less well-established minister to be his "curate," performing some of the duties in one parish while he was doing his responsibilities in the other.herselfThe jokey tone of the phrase "as any body might expect," reminds the reader of how typical it was for mothers of heroines in novels to have died in childbirth by the time the story began. But the joke also reminds us of the grim reality that maternal mortality was quite high in this period, so that for Mrs. Morland to have survived childbirth ten times and to remain in "excellent health" was no small accomplishment.GrayThomas Gray, author "Elegy Written a Country Churchyard," quoted here.Bath Bath is a city in the south west of England that has been a spa and health resort for centuries because of the powerful hot springs on the site. Even before recorded history, people came to the site of what is now Bath, and may have considered it a kind of sacred place, though to be honest we do not know much about religious practices in Britain before the Romans arrived. The Romans called the site Aquae Sulis, or "waters of Sulis," a local deity, and built an elaborate series of bathing and religious facilities over and around the hot springs. (The Roman-era ruins, which are remarkably well preserved, can be visited today). By the eighteenth century, Bath had become one of the most popular spa towns in Europe, with much in the way of residential development and also a number of entertainment centers, such as a theater, restaurants, and dance halls, known as the Assembly Rooms. It was fashionable for people who could afford the expense to take visits of several weeks or months to Bath, during a social season that lasted from October to June. Some people went to Bath for their health, bathing in and drinking the hot waters, which were believed to have medicinal properties. That is not the case, but given how badly contaminated most public water supplies were in this period, anyone who spent a couple of weeks drinking the warm, mineral-rich Bath water instead of the terrible water available in most cities probably would feel better. The concentration of wealthy and fashionable people at Bath also made the city an important scene for matchmaking. When a family arrived at Bath, they let their presence be known to the official Master of Ceremonies and to everyone else in town by signing a book at the Pump Room (about which more later). The Master of Ceremonies would then be responsible for introducing people from different parts of the country to each other, with a particular eye towards making introductions between eligible young women and men. The Master of Ceremonies was also responsible for organizing regular dances at the Assembly Rooms. Jane Austen and her family moved to Bath in 1801 when her father George Austen retired from being a minister in the Church of England. After he died in 1805, Jane, her mother, and her sister Cassandra left the city, staying in a number of different places over the next couple of years until settling in the village of Chawton. Given the way that Austen satirizes Bath in her fiction, it seems reasonable to guess that she did not much enjoy living there and was happy to leave; it is also entirely possible that the three women could not afford to live in the city any longer. Bath continues to be a major tourist site, and much of the architecture and street plan that Austen would have known, and that is depicted in this novel, is preserved.

Bath is a city in the south west of England that has been a spa and health resort for centuries because of the powerful hot springs on the site. Even before recorded history, people came to the site of what is now Bath, and may have considered it a kind of sacred place, though to be honest we do not know much about religious practices in Britain before the Romans arrived. The Romans called the site Aquae Sulis, or "waters of Sulis," a local deity, and built an elaborate series of bathing and religious facilities over and around the hot springs. (The Roman-era ruins, which are remarkably well preserved, can be visited today). By the eighteenth century, Bath had become one of the most popular spa towns in Europe, with much in the way of residential development and also a number of entertainment centers, such as a theater, restaurants, and dance halls, known as the Assembly Rooms. It was fashionable for people who could afford the expense to take visits of several weeks or months to Bath, during a social season that lasted from October to June. Some people went to Bath for their health, bathing in and drinking the hot waters, which were believed to have medicinal properties. That is not the case, but given how badly contaminated most public water supplies were in this period, anyone who spent a couple of weeks drinking the warm, mineral-rich Bath water instead of the terrible water available in most cities probably would feel better. The concentration of wealthy and fashionable people at Bath also made the city an important scene for matchmaking. When a family arrived at Bath, they let their presence be known to the official Master of Ceremonies and to everyone else in town by signing a book at the Pump Room (about which more later). The Master of Ceremonies would then be responsible for introducing people from different parts of the country to each other, with a particular eye towards making introductions between eligible young women and men. The Master of Ceremonies was also responsible for organizing regular dances at the Assembly Rooms. Jane Austen and her family moved to Bath in 1801 when her father George Austen retired from being a minister in the Church of England. After he died in 1805, Jane, her mother, and her sister Cassandra left the city, staying in a number of different places over the next couple of years until settling in the village of Chawton. Given the way that Austen satirizes Bath in her fiction, it seems reasonable to guess that she did not much enjoy living there and was happy to leave; it is also entirely possible that the three women could not afford to live in the city any longer. Bath continues to be a major tourist site, and much of the architecture and street plan that Austen would have known, and that is depicted in this novel, is preserved.

Image: Perspective view of the City of Bath around 1750 by an unknown artist, public domain (British Library)Upper_Rooms The Upper Assembly Rooms. This was one of the two main ballroom complexes in Bath (the other was known as the Lower Assembly Rooms), where regular balls were held for visitors to the city to dance. The Lower Rooms were demolished in the 1930s, but the Upper Rooms are still a tourist destination; the space is also available for hire for special events. The main public spaces in the Upper Rooms are a tea room, a space for card-playing, and a large open ball room for dancing. As shown in the image of a costume party, which is roughly contemporary with the novel, the ball room was lit by enormous chandeliers, had seating for chaperones to watch the dancers in action, and a live orchestra performed on balcony.

The Upper Assembly Rooms. This was one of the two main ballroom complexes in Bath (the other was known as the Lower Assembly Rooms), where regular balls were held for visitors to the city to dance. The Lower Rooms were demolished in the 1930s, but the Upper Rooms are still a tourist destination; the space is also available for hire for special events. The main public spaces in the Upper Rooms are a tea room, a space for card-playing, and a large open ball room for dancing. As shown in the image of a costume party, which is roughly contemporary with the novel, the ball room was lit by enormous chandeliers, had seating for chaperones to watch the dancers in action, and a live orchestra performed on balcony.

Image: Isaac Cruickshank, "The Fancy Ball at the Upper Rooms, Bath, 1825." (Wikimedia Commons)Pump-room The Pump Room was the social center of Bath in this period. New arrivals to the city were expected to let other visitors and the Master of Ceremonies know of their presence by signing a book kept there for that purpose, and we see characters in the novel consulting the book. Visitors would come to the Pump Room to to drink the waters, but also, as in this scene in the novel, to "parade," so that they could see other visitors and be seen by them. The central feature of the Room was (and still is) a pump that brings up hot water from the springs below and dispenses it to guests. There were also stairs leading down to a bathing area where people could bathe or soak in the hot waters. The Pump Room has been remarkably well preserved since Austen's period and is now a fancy restaurant.

The Pump Room was the social center of Bath in this period. New arrivals to the city were expected to let other visitors and the Master of Ceremonies know of their presence by signing a book kept there for that purpose, and we see characters in the novel consulting the book. Visitors would come to the Pump Room to to drink the waters, but also, as in this scene in the novel, to "parade," so that they could see other visitors and be seen by them. The central feature of the Room was (and still is) a pump that brings up hot water from the springs below and dispenses it to guests. There were also stairs leading down to a bathing area where people could bathe or soak in the hot waters. The Pump Room has been remarkably well preserved since Austen's period and is now a fancy restaurant.

Image: Thomas Rowlandson, "The Pump-Room, 1798" (Wikimedia Commons)declared*Vide a letter from Mr. Richardson, No. 97, vol ii. Rambler. [Austen's note.] The Rambler was a periodical series in the early 1750s that was much admired for decades to come. The vast majority of the essays were written by Samuel Johnson, but there were guest contributors, including the novelist Samuel Richardson. In issue #97, first published on February 19, 1751, Richardson writes nostalgically of the way that, a few decades earlier, women had been more modest in public than they were now. The line that the narrator is referencing is this: "That a young lady should be in love, and the love of the young gentleman undeclared, is a heterodoxy which prudence, and even policy, must not allow." Richardson--who was perhaps Austen's favorite novelist--is writing anonymously here, and perhaps tongue in cheek; if not, the narrator is surely treating the quotation with a grain of salt.

It is easy to see why Austen might have been frustrated with Crosby (who never explained his reasoning) for dragging his heels on publishing Susan, because the book is in part responding to the boom for Gothic fiction that took place in the 1780s and 1790s. There were scores of such works published in those decades, and many of them are referred to in the course of Northanger Abbey: The Castle of Wolfenbach by Eliza Parsons, Clermont by Regina Roche, The Necromancer by Lawrence Flammenberg and others. But above all, Austen and her heroine Catherine Morland refer to the works of Ann Radcliffe, one of the most popular writers of the entire period. Radcliffe’s gothic fictions such as The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797) were enormously popular in the period and remain enjoyable today. Northanger Abbey is in part a satire on these books, but it is also clear that Austen, like her heroine Catherine Morland, loved Radcliffe’s gothic novels. As much as anything else, Northanger Abbey is testimony to the power of novels, and of reading in general. Catherine Morland comes to learn that gothic novels are not a particularly good guide to how the real world works, but reading novels has also helped make her imaginative and empathetic, one of the most appealing of all of Austen’s heroines. If anything, Catherine needs to read more novels, novels perhaps like those by Austen herself. two_good_livingsThat is, Richard Morland receives income from his work as the pastor of two different parishes in the Church of England. Clergymen in the Church in this period would be granted a "living," sometimes also called a "benefice," to support themselves, and most such livings, which guaranteed an annual income that varied on the size and wealth of the area, would be associated with a particular parish. In most cases, this money would have come from the hierarchy of the Church of England, but was also sometimes in the gift of the most powerful local landowner in a given area. A clergyman generally held such a living or livings until he retired or died. As Richard Morland does, a successful clergyman could hold more than two livings at one time--usually in adjacent or nearby parishes--and thereby enhance his income. If a clergyman had more than one living, he might hire a younger, less well-established minister to be his "curate," performing some of the duties in one parish while he was doing his responsibilities in the other.herselfThe jokey tone of the phrase "as any body might expect," reminds the reader of how typical it was for mothers of heroines in novels to have died in childbirth by the time the story began. But the joke also reminds us of the grim reality that maternal mortality was quite high in this period, so that for Mrs. Morland to have survived childbirth ten times and to remain in "excellent health" was no small accomplishment.GrayThomas Gray, author "Elegy Written a Country Churchyard," quoted here.Bath

It is easy to see why Austen might have been frustrated with Crosby (who never explained his reasoning) for dragging his heels on publishing Susan, because the book is in part responding to the boom for Gothic fiction that took place in the 1780s and 1790s. There were scores of such works published in those decades, and many of them are referred to in the course of Northanger Abbey: The Castle of Wolfenbach by Eliza Parsons, Clermont by Regina Roche, The Necromancer by Lawrence Flammenberg and others. But above all, Austen and her heroine Catherine Morland refer to the works of Ann Radcliffe, one of the most popular writers of the entire period. Radcliffe’s gothic fictions such as The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797) were enormously popular in the period and remain enjoyable today. Northanger Abbey is in part a satire on these books, but it is also clear that Austen, like her heroine Catherine Morland, loved Radcliffe’s gothic novels. As much as anything else, Northanger Abbey is testimony to the power of novels, and of reading in general. Catherine Morland comes to learn that gothic novels are not a particularly good guide to how the real world works, but reading novels has also helped make her imaginative and empathetic, one of the most appealing of all of Austen’s heroines. If anything, Catherine needs to read more novels, novels perhaps like those by Austen herself. two_good_livingsThat is, Richard Morland receives income from his work as the pastor of two different parishes in the Church of England. Clergymen in the Church in this period would be granted a "living," sometimes also called a "benefice," to support themselves, and most such livings, which guaranteed an annual income that varied on the size and wealth of the area, would be associated with a particular parish. In most cases, this money would have come from the hierarchy of the Church of England, but was also sometimes in the gift of the most powerful local landowner in a given area. A clergyman generally held such a living or livings until he retired or died. As Richard Morland does, a successful clergyman could hold more than two livings at one time--usually in adjacent or nearby parishes--and thereby enhance his income. If a clergyman had more than one living, he might hire a younger, less well-established minister to be his "curate," performing some of the duties in one parish while he was doing his responsibilities in the other.herselfThe jokey tone of the phrase "as any body might expect," reminds the reader of how typical it was for mothers of heroines in novels to have died in childbirth by the time the story began. But the joke also reminds us of the grim reality that maternal mortality was quite high in this period, so that for Mrs. Morland to have survived childbirth ten times and to remain in "excellent health" was no small accomplishment.GrayThomas Gray, author "Elegy Written a Country Churchyard," quoted here.Bath Bath is a city in the south west of England that has been a spa and health resort for centuries because of the powerful hot springs on the site. Even before recorded history, people came to the site of what is now Bath, and may have considered it a kind of sacred place, though to be honest we do not know much about religious practices in Britain before the Romans arrived. The Romans called the site Aquae Sulis, or "waters of Sulis," a local deity, and built an elaborate series of bathing and religious facilities over and around the hot springs. (The Roman-era ruins, which are remarkably well preserved, can be visited today). By the eighteenth century, Bath had become one of the most popular spa towns in Europe, with much in the way of residential development and also a number of entertainment centers, such as a theater, restaurants, and dance halls, known as the Assembly Rooms. It was fashionable for people who could afford the expense to take visits of several weeks or months to Bath, during a social season that lasted from October to June. Some people went to Bath for their health, bathing in and drinking the hot waters, which were believed to have medicinal properties. That is not the case, but given how badly contaminated most public water supplies were in this period, anyone who spent a couple of weeks drinking the warm, mineral-rich Bath water instead of the terrible water available in most cities probably would feel better. The concentration of wealthy and fashionable people at Bath also made the city an important scene for matchmaking. When a family arrived at Bath, they let their presence be known to the official Master of Ceremonies and to everyone else in town by signing a book at the Pump Room (about which more later). The Master of Ceremonies would then be responsible for introducing people from different parts of the country to each other, with a particular eye towards making introductions between eligible young women and men. The Master of Ceremonies was also responsible for organizing regular dances at the Assembly Rooms. Jane Austen and her family moved to Bath in 1801 when her father George Austen retired from being a minister in the Church of England. After he died in 1805, Jane, her mother, and her sister Cassandra left the city, staying in a number of different places over the next couple of years until settling in the village of Chawton. Given the way that Austen satirizes Bath in her fiction, it seems reasonable to guess that she did not much enjoy living there and was happy to leave; it is also entirely possible that the three women could not afford to live in the city any longer. Bath continues to be a major tourist site, and much of the architecture and street plan that Austen would have known, and that is depicted in this novel, is preserved.

Bath is a city in the south west of England that has been a spa and health resort for centuries because of the powerful hot springs on the site. Even before recorded history, people came to the site of what is now Bath, and may have considered it a kind of sacred place, though to be honest we do not know much about religious practices in Britain before the Romans arrived. The Romans called the site Aquae Sulis, or "waters of Sulis," a local deity, and built an elaborate series of bathing and religious facilities over and around the hot springs. (The Roman-era ruins, which are remarkably well preserved, can be visited today). By the eighteenth century, Bath had become one of the most popular spa towns in Europe, with much in the way of residential development and also a number of entertainment centers, such as a theater, restaurants, and dance halls, known as the Assembly Rooms. It was fashionable for people who could afford the expense to take visits of several weeks or months to Bath, during a social season that lasted from October to June. Some people went to Bath for their health, bathing in and drinking the hot waters, which were believed to have medicinal properties. That is not the case, but given how badly contaminated most public water supplies were in this period, anyone who spent a couple of weeks drinking the warm, mineral-rich Bath water instead of the terrible water available in most cities probably would feel better. The concentration of wealthy and fashionable people at Bath also made the city an important scene for matchmaking. When a family arrived at Bath, they let their presence be known to the official Master of Ceremonies and to everyone else in town by signing a book at the Pump Room (about which more later). The Master of Ceremonies would then be responsible for introducing people from different parts of the country to each other, with a particular eye towards making introductions between eligible young women and men. The Master of Ceremonies was also responsible for organizing regular dances at the Assembly Rooms. Jane Austen and her family moved to Bath in 1801 when her father George Austen retired from being a minister in the Church of England. After he died in 1805, Jane, her mother, and her sister Cassandra left the city, staying in a number of different places over the next couple of years until settling in the village of Chawton. Given the way that Austen satirizes Bath in her fiction, it seems reasonable to guess that she did not much enjoy living there and was happy to leave; it is also entirely possible that the three women could not afford to live in the city any longer. Bath continues to be a major tourist site, and much of the architecture and street plan that Austen would have known, and that is depicted in this novel, is preserved. Image: Perspective view of the City of Bath around 1750 by an unknown artist, public domain (British Library)Upper_Rooms

The Upper Assembly Rooms. This was one of the two main ballroom complexes in Bath (the other was known as the Lower Assembly Rooms), where regular balls were held for visitors to the city to dance. The Lower Rooms were demolished in the 1930s, but the Upper Rooms are still a tourist destination; the space is also available for hire for special events. The main public spaces in the Upper Rooms are a tea room, a space for card-playing, and a large open ball room for dancing. As shown in the image of a costume party, which is roughly contemporary with the novel, the ball room was lit by enormous chandeliers, had seating for chaperones to watch the dancers in action, and a live orchestra performed on balcony.

The Upper Assembly Rooms. This was one of the two main ballroom complexes in Bath (the other was known as the Lower Assembly Rooms), where regular balls were held for visitors to the city to dance. The Lower Rooms were demolished in the 1930s, but the Upper Rooms are still a tourist destination; the space is also available for hire for special events. The main public spaces in the Upper Rooms are a tea room, a space for card-playing, and a large open ball room for dancing. As shown in the image of a costume party, which is roughly contemporary with the novel, the ball room was lit by enormous chandeliers, had seating for chaperones to watch the dancers in action, and a live orchestra performed on balcony.Image: Isaac Cruickshank, "The Fancy Ball at the Upper Rooms, Bath, 1825." (Wikimedia Commons)Pump-room

The Pump Room was the social center of Bath in this period. New arrivals to the city were expected to let other visitors and the Master of Ceremonies know of their presence by signing a book kept there for that purpose, and we see characters in the novel consulting the book. Visitors would come to the Pump Room to to drink the waters, but also, as in this scene in the novel, to "parade," so that they could see other visitors and be seen by them. The central feature of the Room was (and still is) a pump that brings up hot water from the springs below and dispenses it to guests. There were also stairs leading down to a bathing area where people could bathe or soak in the hot waters. The Pump Room has been remarkably well preserved since Austen's period and is now a fancy restaurant.

The Pump Room was the social center of Bath in this period. New arrivals to the city were expected to let other visitors and the Master of Ceremonies know of their presence by signing a book kept there for that purpose, and we see characters in the novel consulting the book. Visitors would come to the Pump Room to to drink the waters, but also, as in this scene in the novel, to "parade," so that they could see other visitors and be seen by them. The central feature of the Room was (and still is) a pump that brings up hot water from the springs below and dispenses it to guests. There were also stairs leading down to a bathing area where people could bathe or soak in the hot waters. The Pump Room has been remarkably well preserved since Austen's period and is now a fancy restaurant.

Image: Thomas Rowlandson, "The Pump-Room, 1798" (Wikimedia Commons)declared*Vide a letter from Mr. Richardson, No. 97, vol ii. Rambler. [Austen's note.] The Rambler was a periodical series in the early 1750s that was much admired for decades to come. The vast majority of the essays were written by Samuel Johnson, but there were guest contributors, including the novelist Samuel Richardson. In issue #97, first published on February 19, 1751, Richardson writes nostalgically of the way that, a few decades earlier, women had been more modest in public than they were now. The line that the narrator is referencing is this: "That a young lady should be in love, and the love of the young gentleman undeclared, is a heterodoxy which prudence, and even policy, must not allow." Richardson--who was perhaps Austen's favorite novelist--is writing anonymously here, and perhaps tongue in cheek; if not, the narrator is surely treating the quotation with a grain of salt.

NORTHANGER ABBEY:TitleTitleNorthanger Abbey is both Jane Austen’s first and her last novel. We know that she wrote a draft of the book under the title Susan in the 1790s, and reached agreement with the London publisher Benjamin Crosby to sell the copyright to him for £10 in 1803. But Crosby sat on the manuscript for years, which seems to have frustrated Austen. In 1816, she was finally able to purchase the copyright back from him, and it seems that she did some revisions on the text, the most obvious of which was changing the name of the heroine from Susan to Catherine (a novel with the title Susan had come out in the meantime). But Austen was already sick by this point with what would be her final illness; she died on July 18, 1817, leaving this and the manuscript for the novel that became known as Persuasion in manuscript. Austen’s brother Henry and her sister Cassandra gave the two novels their titles, and Henry, who had often been Austen's intermediary with London publishers, arranged for them to be published together. The two novels, in a set of four small volumes, two for each of them, were published in late 1817, with an official publication year of 1818.

It is easy to see why Austen might have been frustrated with Crosby (who never explained his reasoning) for dragging his heels on publishing Susan, because the book is in part responding to the boom for Gothic fiction that took place in the 1780s and 1790s. There were scores of such works published in those decades, and many of them are referred to in the course of Northanger Abbey: The Castle of Wolfenbach by Eliza Parsons, Clermont by Regina Roche, The Necromancer by Lawrence Flammenberg and others. But above all, Austen and her heroine Catherine Morland refer to the works of Ann Radcliffe, one of the most popular writers of the entire period. Radcliffe’s gothic fictions such as The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797) were enormously popular in the period and remain enjoyable today. Northanger Abbey is in part a satire on these books, but it is also clear that Austen, like her heroine Catherine Morland, loved Radcliffe’s gothic novels. As much as anything else, Northanger Abbey is testimony to the power of novels, and of reading in general. Catherine Morland comes to learn that gothic novels are not a particularly good guide to how the real world works, but reading novels has also helped make her imaginative and empathetic, one of the most appealing of all of Austen’s heroines. If anything, Catherine needs to read more novels, novels perhaps like those by Austen herself.

It is easy to see why Austen might have been frustrated with Crosby (who never explained his reasoning) for dragging his heels on publishing Susan, because the book is in part responding to the boom for Gothic fiction that took place in the 1780s and 1790s. There were scores of such works published in those decades, and many of them are referred to in the course of Northanger Abbey: The Castle of Wolfenbach by Eliza Parsons, Clermont by Regina Roche, The Necromancer by Lawrence Flammenberg and others. But above all, Austen and her heroine Catherine Morland refer to the works of Ann Radcliffe, one of the most popular writers of the entire period. Radcliffe’s gothic fictions such as The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797) were enormously popular in the period and remain enjoyable today. Northanger Abbey is in part a satire on these books, but it is also clear that Austen, like her heroine Catherine Morland, loved Radcliffe’s gothic novels. As much as anything else, Northanger Abbey is testimony to the power of novels, and of reading in general. Catherine Morland comes to learn that gothic novels are not a particularly good guide to how the real world works, but reading novels has also helped make her imaginative and empathetic, one of the most appealing of all of Austen’s heroines. If anything, Catherine needs to read more novels, novels perhaps like those by Austen herself.

AND

PERSUASION.

BY THE AUTHOR OF "PRIDE AND PREJUDICE,"

"MANSFIELD-PARK," &c.

WITH A BIOGRAPHICAL NOTICE OF THE

AUTHOR.

IN FOUR VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE-STREET.

1817

It is easy to see why Austen might have been frustrated with Crosby (who never explained his reasoning) for dragging his heels on publishing Susan, because the book is in part responding to the boom for Gothic fiction that took place in the 1780s and 1790s. There were scores of such works published in those decades, and many of them are referred to in the course of Northanger Abbey: The Castle of Wolfenbach by Eliza Parsons, Clermont by Regina Roche, The Necromancer by Lawrence Flammenberg and others. But above all, Austen and her heroine Catherine Morland refer to the works of Ann Radcliffe, one of the most popular writers of the entire period. Radcliffe’s gothic fictions such as The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797) were enormously popular in the period and remain enjoyable today. Northanger Abbey is in part a satire on these books, but it is also clear that Austen, like her heroine Catherine Morland, loved Radcliffe’s gothic novels. As much as anything else, Northanger Abbey is testimony to the power of novels, and of reading in general. Catherine Morland comes to learn that gothic novels are not a particularly good guide to how the real world works, but reading novels has also helped make her imaginative and empathetic, one of the most appealing of all of Austen’s heroines. If anything, Catherine needs to read more novels, novels perhaps like those by Austen herself.

It is easy to see why Austen might have been frustrated with Crosby (who never explained his reasoning) for dragging his heels on publishing Susan, because the book is in part responding to the boom for Gothic fiction that took place in the 1780s and 1790s. There were scores of such works published in those decades, and many of them are referred to in the course of Northanger Abbey: The Castle of Wolfenbach by Eliza Parsons, Clermont by Regina Roche, The Necromancer by Lawrence Flammenberg and others. But above all, Austen and her heroine Catherine Morland refer to the works of Ann Radcliffe, one of the most popular writers of the entire period. Radcliffe’s gothic fictions such as The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797) were enormously popular in the period and remain enjoyable today. Northanger Abbey is in part a satire on these books, but it is also clear that Austen, like her heroine Catherine Morland, loved Radcliffe’s gothic novels. As much as anything else, Northanger Abbey is testimony to the power of novels, and of reading in general. Catherine Morland comes to learn that gothic novels are not a particularly good guide to how the real world works, but reading novels has also helped make her imaginative and empathetic, one of the most appealing of all of Austen’s heroines. If anything, Catherine needs to read more novels, novels perhaps like those by Austen herself. AND

PERSUASION.

BY THE AUTHOR OF "PRIDE AND PREJUDICE,"

"MANSFIELD-PARK," &c.

WITH A BIOGRAPHICAL NOTICE OF THE

AUTHOR.

IN FOUR VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE-STREET.

1817