The Rambler No. 4

By

Samuel Johnson

Quintus Horatius Flaccus, or Horace, was a Roman lyric poet of the 1st

century BCE. The image above is a broze portrait medal containing his

likeness, dating to the 4th century CE, housed in the Bibliothèque

Nationale, Paris (Encyclopedia Britannica). - [TH]heroicHeroic romance is a genre that flourished

during the 17th century and remained popular, as parodied by Charlotte Lennox in

The Female Quixote, into the 18th. It had a profound

influence on the development of the novel, though many writers of the 18th

century would work to dissociate the genres, as Johnson does here. Formaally

loose in structure, heroic romances also "deliberately eschew[ed]

contemporaneity"; their plots featured courtly lovers engaged in "heroic stories

of love and war in a remote and idealized past" (Shellinger, Encyclopedia of the Novel, 1046). Some

representative heroic romances include Euphues by John

Lyly, L'Astree by Honore d'Urfe, and Clelie by Madame de Scudery. - [TH]ScaligerJulius Caesar Scaliger (1484-1558) was a Franco-Italian humanist

polymath most widely-known for his Poetices Libri

Septem (1561). For more information on the Poetices, see Bernard Weinberg's "Scaliger versus Aristotle on Poetics" (1942)

and this review by David

Marsh of a new edition and German translation of the whole.

Scaliger critiques the poetry of Italian humanist Giovanni

Pontano (1429-1503).

- [TH]closet

Quintus Horatius Flaccus, or Horace, was a Roman lyric poet of the 1st

century BCE. The image above is a broze portrait medal containing his

likeness, dating to the 4th century CE, housed in the Bibliothèque

Nationale, Paris (Encyclopedia Britannica). - [TH]heroicHeroic romance is a genre that flourished

during the 17th century and remained popular, as parodied by Charlotte Lennox in

The Female Quixote, into the 18th. It had a profound

influence on the development of the novel, though many writers of the 18th

century would work to dissociate the genres, as Johnson does here. Formaally

loose in structure, heroic romances also "deliberately eschew[ed]

contemporaneity"; their plots featured courtly lovers engaged in "heroic stories

of love and war in a remote and idealized past" (Shellinger, Encyclopedia of the Novel, 1046). Some

representative heroic romances include Euphues by John

Lyly, L'Astree by Honore d'Urfe, and Clelie by Madame de Scudery. - [TH]ScaligerJulius Caesar Scaliger (1484-1558) was a Franco-Italian humanist

polymath most widely-known for his Poetices Libri

Septem (1561). For more information on the Poetices, see Bernard Weinberg's "Scaliger versus Aristotle on Poetics" (1942)

and this review by David

Marsh of a new edition and German translation of the whole.

Scaliger critiques the poetry of Italian humanist Giovanni

Pontano (1429-1503).

- [TH]closet In the eighteenth century, a "closet" was a small office or

private room leading off of a bedroom; here, individuals would conduct business,

write letters, read, or converse with close acquaintances. It was not used to

store clothes. For more information, see Daily Life in

18th-Century England (85-86), or Danielle Bobker's "Literature and Culture of the Closet in the Eighteenth

Century," from which site the accompanying image, showing the Green

Closet at Frogmore, has been drawn. - [TH]plus_onerisIn Horace's Epistles 2.1, this quote

appears at line 170. In this epistle to Augustus, Horace is mounting a

defense of contemporary poetry and decrying the poor taste of the public. In

particular he argues that though comic subjects are thought easier to write,

they are actually more challenging than tragic subjects because readers give

them less "indulgence." Johnson will put this "indulgence" in terms of the

readers' familiarity with the more common subjects of comedy (Perseus

Project). - [TH]PlinyJohnson alludes here to a

story from Pliny the Elder's Natural History

(35.36). - [TH]VenusRoman counterpart to the Greek goddess

Aphrodite, Venus is a signifier of love, sex, propsperity, and desire (Wikipedia). - [TH]ApellesApelles of Kos, a Greek painter of the 4th century BCE

(Wikipedia).

Johnson here alludes to a lost painting of Venus Anadyomenes, or Venus rising

from the sea. - [TH]audienceThis is one of the most-quoted moments

in the essay. Here, Johnson is making the case that the young, untutored,

inexperienced minds that form the primary audience of the novel are easily led

astray by the familiarity of their subjects and the verisimilitude of their

style. - [TH]historiesJohnson here uses the term "familiar history" to describe

the probable fictions produced by "our present Writers." The term suggests the

truth-value associated with many eighteenth-century fictions that, like Robinson Crusoe (1719) or Pamela

(1740), were advertised as having been largely written by the characters

themselves. These are supposedly true histories, memoirs, or other accounts of

people who would seem familiar to contemporary audiences. - [TH]possession Here Johnson

argues that representations which are rendered in so familiar and realistic a

manner are especially dangerous to untutored minds because they seem to be truth

rather than fiction; he therefore cautions that authors provide the best models

for behavior and the cultivation of the mind. Johnson references

eighteenth-century thought about the power of the imagination to affect the body

regardless of the will, like that discussed by Michele de Montaigne in "Of the Power of the Imagination." For

information about the power of the female imagination to create monstrous

beings, see, among other works, Marie Hélène Huet's

Monstrous Imagination (1993). - [TH]promiscuous"Promiscuous"

here refers to a lack of distinction or discrimination; it is not primarily

sexual. See this Google

N-Gram graph charting the usage of the term over time. - [TH]increaseIn

this passage, Johnson articulates his sense of the purpose of novelistic

writing. For him, the purpose of fiction is education, as it provides a kind of

experience that is protected from the dangers that might accompany such actions

in real life. - [TH]Swift

In the eighteenth century, a "closet" was a small office or

private room leading off of a bedroom; here, individuals would conduct business,

write letters, read, or converse with close acquaintances. It was not used to

store clothes. For more information, see Daily Life in

18th-Century England (85-86), or Danielle Bobker's "Literature and Culture of the Closet in the Eighteenth

Century," from which site the accompanying image, showing the Green

Closet at Frogmore, has been drawn. - [TH]plus_onerisIn Horace's Epistles 2.1, this quote

appears at line 170. In this epistle to Augustus, Horace is mounting a

defense of contemporary poetry and decrying the poor taste of the public. In

particular he argues that though comic subjects are thought easier to write,

they are actually more challenging than tragic subjects because readers give

them less "indulgence." Johnson will put this "indulgence" in terms of the

readers' familiarity with the more common subjects of comedy (Perseus

Project). - [TH]PlinyJohnson alludes here to a

story from Pliny the Elder's Natural History

(35.36). - [TH]VenusRoman counterpart to the Greek goddess

Aphrodite, Venus is a signifier of love, sex, propsperity, and desire (Wikipedia). - [TH]ApellesApelles of Kos, a Greek painter of the 4th century BCE

(Wikipedia).

Johnson here alludes to a lost painting of Venus Anadyomenes, or Venus rising

from the sea. - [TH]audienceThis is one of the most-quoted moments

in the essay. Here, Johnson is making the case that the young, untutored,

inexperienced minds that form the primary audience of the novel are easily led

astray by the familiarity of their subjects and the verisimilitude of their

style. - [TH]historiesJohnson here uses the term "familiar history" to describe

the probable fictions produced by "our present Writers." The term suggests the

truth-value associated with many eighteenth-century fictions that, like Robinson Crusoe (1719) or Pamela

(1740), were advertised as having been largely written by the characters

themselves. These are supposedly true histories, memoirs, or other accounts of

people who would seem familiar to contemporary audiences. - [TH]possession Here Johnson

argues that representations which are rendered in so familiar and realistic a

manner are especially dangerous to untutored minds because they seem to be truth

rather than fiction; he therefore cautions that authors provide the best models

for behavior and the cultivation of the mind. Johnson references

eighteenth-century thought about the power of the imagination to affect the body

regardless of the will, like that discussed by Michele de Montaigne in "Of the Power of the Imagination." For

information about the power of the female imagination to create monstrous

beings, see, among other works, Marie Hélène Huet's

Monstrous Imagination (1993). - [TH]promiscuous"Promiscuous"

here refers to a lack of distinction or discrimination; it is not primarily

sexual. See this Google

N-Gram graph charting the usage of the term over time. - [TH]increaseIn

this passage, Johnson articulates his sense of the purpose of novelistic

writing. For him, the purpose of fiction is education, as it provides a kind of

experience that is protected from the dangers that might accompany such actions

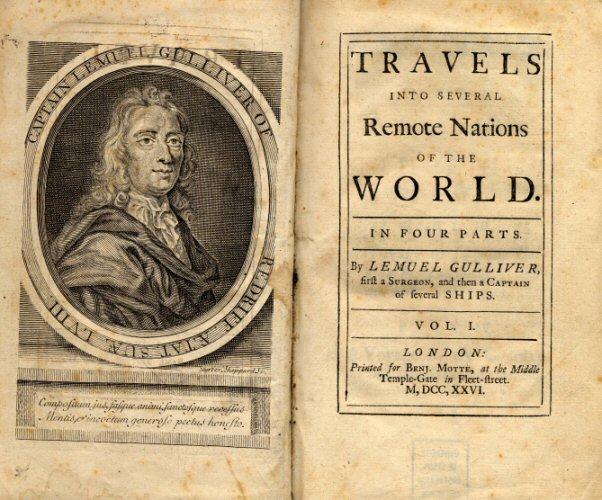

in real life. - [TH]Swift Jonathan Swift, an Anglo-Irish satiric author of the early 18th century,

is most well-known today for writing Gulliver's

Travels. The title page to the first edition of Gulliver's Travels, reproduced from Wikimedia Commons, is above.

For more information on Swift, see this

biographical essay by Ian Campbell Ross (2016), and readers may

also be interested in this 2017 online

exhibition about Swift from the Library of Trinity College,

Dublin. - [TH]gratefulFrom the second

volume of the Miscellanies, compiled by Jonathan

Swift and Alexander Pope, this particular quotation is from Thoughts on Various Subjects," a

collection of witty aphorisms by Pope and contained in the second

volume. - [TH]partsAccording

to the Oxford English Dictionary, "part" used in this

sense (II.15) refers to "A personal quality or attribute, esp. of an

intellectual kind; an ability, gift, or talent." - [TH]witsTo be a "wit" in the eighteenth century was to be clever.

But it could also be a term of derision, referring to a set of people who

claimed false cleverness. Here, Johnson is suggesting that such people would

rather be thought by others to be clever, even at the expense of being thought

wicked. See Jack

Lynch's "Guide to Eighteenth-Century Vocabulary," which includes a

definition of this word. - [TH]publishersPublishers John Payne and Joseph

Boquet joined forces at mid-century, working from the center of the English

book trade in Paternoster Row. The pair published The

Rambler from 1750, bringing them much profit. It is said that the

publishers offered Johnson the astonishing sum of 2 guineas per issue. For a

brief overview of the printers, see footnote 2 to a 1750 letter between

Samuel Johnson and Charlotte Lennox (4), discussing the publication of her

Poems, in Norbert

Schürer's Charlotte Lennox: Correspondence and

Miscellaneous Documents. - [TH]

Jonathan Swift, an Anglo-Irish satiric author of the early 18th century,

is most well-known today for writing Gulliver's

Travels. The title page to the first edition of Gulliver's Travels, reproduced from Wikimedia Commons, is above.

For more information on Swift, see this

biographical essay by Ian Campbell Ross (2016), and readers may

also be interested in this 2017 online

exhibition about Swift from the Library of Trinity College,

Dublin. - [TH]gratefulFrom the second

volume of the Miscellanies, compiled by Jonathan

Swift and Alexander Pope, this particular quotation is from Thoughts on Various Subjects," a

collection of witty aphorisms by Pope and contained in the second

volume. - [TH]partsAccording

to the Oxford English Dictionary, "part" used in this

sense (II.15) refers to "A personal quality or attribute, esp. of an

intellectual kind; an ability, gift, or talent." - [TH]witsTo be a "wit" in the eighteenth century was to be clever.

But it could also be a term of derision, referring to a set of people who

claimed false cleverness. Here, Johnson is suggesting that such people would

rather be thought by others to be clever, even at the expense of being thought

wicked. See Jack

Lynch's "Guide to Eighteenth-Century Vocabulary," which includes a

definition of this word. - [TH]publishersPublishers John Payne and Joseph

Boquet joined forces at mid-century, working from the center of the English

book trade in Paternoster Row. The pair published The

Rambler from 1750, bringing them much profit. It is said that the

publishers offered Johnson the astonishing sum of 2 guineas per issue. For a

brief overview of the printers, see footnote 2 to a 1750 letter between

Samuel Johnson and Charlotte Lennox (4), discussing the publication of her

Poems, in Norbert

Schürer's Charlotte Lennox: Correspondence and

Miscellaneous Documents. - [TH]RAMBLER.

NUMB. 4. Price 2 d.pricepriceThis issue cost two pence. In the eighteenth-century coinage system, 12 pence made a shilling, and 20 shillings made a pound. According to the Old Bailey Online, "A waterman would expect six pence to take you from Westminster to London Bridge, while a barber asked the same to dress your wig and give you a shave." While two pence was not out of reach for most people, the publication frequency of The Rambler and similar items would make regular personal purchasing out of the realm of possibility for most. However, men might read a copy in a coffeeshop, entry to which, in the seventeenth century, was a penny. For a deeper look at money, purchasing power, and income, see Robert Hume's article "The Value of Money in Eighteenth-Century England: Incomes, Prices, Buying Power—-and Some Problems in Cultural Economics" in Huntington Library Quarterly (2015). - [TH]

SATURDAY, 31 March 1750

To be Continued on TUESDAYS and SATURDAYS

Simul et jucunda et idonea dicere Vitae.epigraphepigraphFrom Horace's Ars Poetica 334: 'to deliver at once both the pleasures and the necessaries of life" (Perseus Project). - [TH] HOR[ace]HoraceHorace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus, or Horace, was a Roman lyric poet of the 1st

century BCE. The image above is a broze portrait medal containing his

likeness, dating to the 4th century CE, housed in the Bibliothèque

Nationale, Paris (Encyclopedia Britannica). - [TH]

Quintus Horatius Flaccus, or Horace, was a Roman lyric poet of the 1st

century BCE. The image above is a broze portrait medal containing his

likeness, dating to the 4th century CE, housed in the Bibliothèque

Nationale, Paris (Encyclopedia Britannica). - [TH]

THE Works of Fiction, with which the present Generation seems more particularly delighted, are such as exhibit Life in its true State, diversified only by Accidents that daily happen in the World, and influenced by those Passions and Qualities which are really to be found in conversing with Mankind.

THIS Kind of Writing may be termed not improperly the Comedy of Romance, and is to be conducted nearly by the Rules of Comic Poetry. Its Province is to bring about natural Events by easy Means, and to keep up Curiosity without the Help of Wonder: it is therefore precluded from the Machines and Expedients of the Heroic Romanceheroic, heroicHeroic romance is a genre that flourished during the 17th century and remained popular, as parodied by Charlotte Lennox in The Female Quixote, into the 18th. It had a profound influence on the development of the novel, though many writers of the 18th century would work to dissociate the genres, as Johnson does here. Formaally loose in structure, heroic romances also "deliberately eschew[ed] contemporaneity"; their plots featured courtly lovers engaged in "heroic stories of love and war in a remote and idealized past" (Shellinger, Encyclopedia of the Novel, 1046). Some representative heroic romances include Euphues by John Lyly, L'Astree by Honore d'Urfe, and Clelie by Madame de Scudery. - [TH] and can neither employ Giants to snatch away a Lady from the nuptial Rites, nor Knights to bring her back from Captivity; it can neither bewilder its Personages in Desarts, nor lodge them in imaginary Castles.

I REMEMBER a Remark made by ScaligerScaligerScaligerJulius Caesar Scaliger (1484-1558) was a Franco-Italian humanist polymath most widely-known for his Poetices Libri Septem (1561). For more information on the Poetices, see Bernard Weinberg's "Scaliger versus Aristotle on Poetics" (1942) and this review by David Marsh of a new edition and German translation of the whole. Scaliger critiques the poetry of Italian humanist Giovanni Pontano (1429-1503). - [TH] upon Potanus, that all his Writings are filled with Images, and that

![Page [19]](https://anthologyassetsdev.lib.virginia.edu/johnson-rambler-4/pageImages/19.jpg)